Japan Strengthens Anti-Bribery Enforcement: Expanded Penalties and Scope for Foreign Public Official Bribery

TL;DR

- A May 2024 amendment to the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (“UCPA”) doubles the maximum corporate fine for bribery of foreign public officials to ¥600 million (≈ US $4 m) or “loss avoided,” whichever is higher.

- “Officials” now expressly include employees of foreign-government-controlled funds and international organisations, aligning with OECD guidance.

- Expanded jurisdiction, document-access powers and longer limitation periods signal more aggressive Special Investigation Department (SID) actions—often in cooperation with the US DOJ/SEC.

Table of Contents

- Overview of the 2024 UCPA Reform

- Expanded Definition of “Foreign Public Official”

- Harsher Criminal & Administrative Penalties

- Enforcement Powers and Cross-Border Cooperation

- Compliance Takeaways for Multinationals

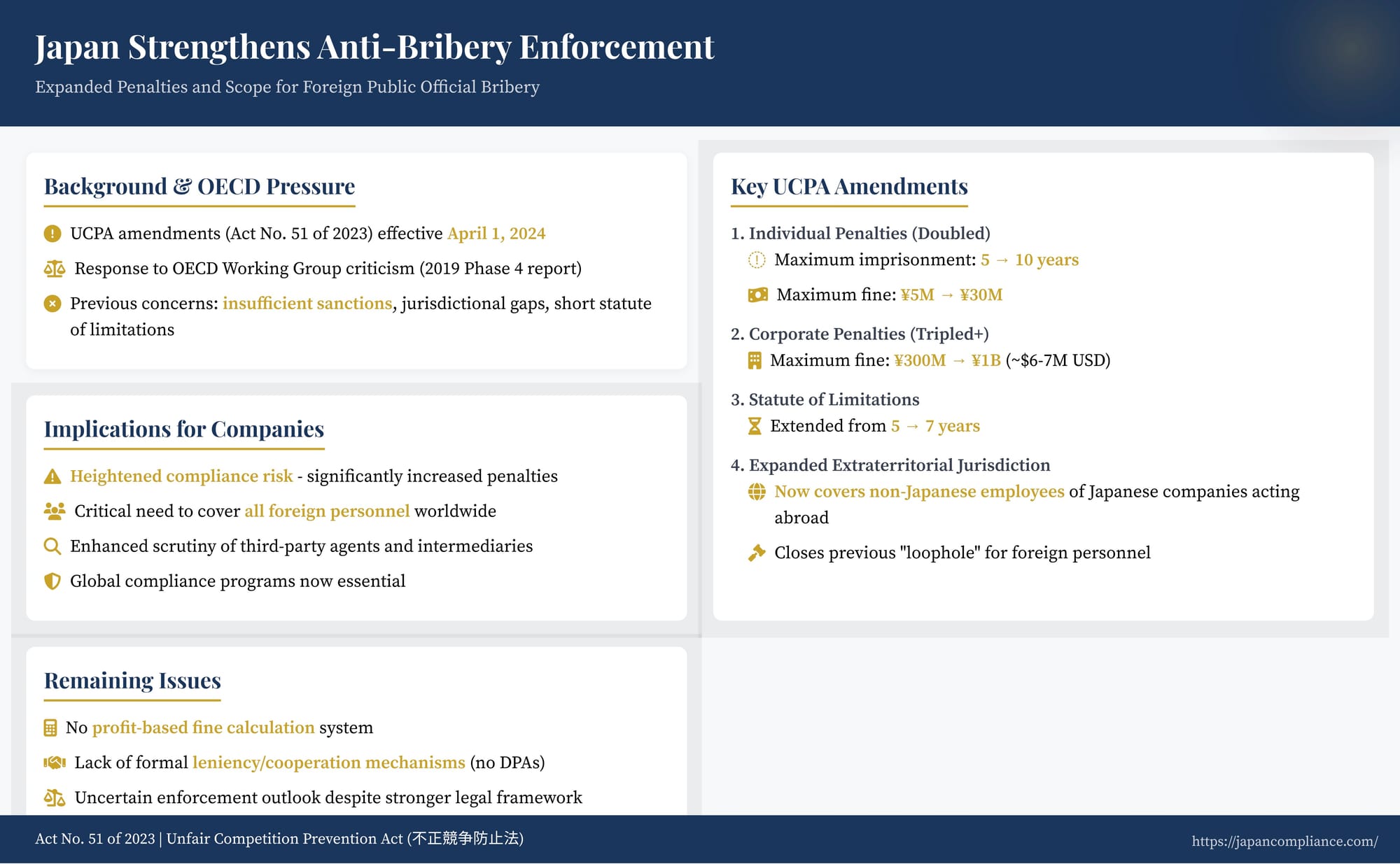

In a significant move to bolster its fight against transnational corruption, Japan enacted key amendments to its Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法, Fusei Kyōsō Bōshi Hō, hereafter "UCPA") in 2023 (Act No. 51 of 2023). These changes, which largely took effect on April 1, 2024, introduce substantially harsher penalties for bribing foreign public officials and, critically, expand the law's extraterritorial reach to cover acts committed abroad by foreign nationals working for Japanese companies. This legislative overhaul responds directly to long-standing international pressure, particularly from the OECD Working Group on Bribery, and significantly elevates the compliance risks for multinational corporations with operations or subsidiaries based in Japan.

Background: Addressing International Concerns

Japan ratified the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions in 1998 and incorporated anti-bribery provisions into the UCPA shortly thereafter. However, Japan's enforcement record has historically lagged behind other major economies, drawing repeated criticism from the OECD Working Group.

In its Phase 4 evaluation report adopted in 2019, the Working Group issued several priority recommendations urging Japan to strengthen its foreign bribery framework. Key concerns included:

- Insufficient Sanctions: Penalties for both individuals and corporations were deemed relatively low compared to other OECD countries and other domestic economic crimes in Japan, potentially lacking sufficient deterrent effect. The report noted that imprisonment sentences had consistently been suspended, and fines imposed often seemed disproportionate to the illicit gains.

- Jurisdictional Gaps: A significant concern was the perceived "major loophole" regarding bribery committed entirely outside Japan by non-Japanese employees of Japanese companies, without the direct involvement of Japanese nationals or actions within Japan. Under previous interpretations of territorial and nationality principles, prosecuting such cases was difficult.

- Statute of Limitations: The existing 5-year statute of limitations was considered potentially too short for complex transnational bribery investigations.

- Lack of Guidance: The report also called for clearer guidance on factors considered during investigation and prosecution, such as self-reporting and cooperation.

The 2023 amendments directly address several of these priority concerns, signaling a renewed commitment by Japan to align its anti-bribery regime more closely with international standards and expectations.

Key Amendments in the 2023 UCPA Revision

The amendments introduce substantial changes to Articles 21 (Penal Provisions) and 22 (Dual Liability/Corporate Penalties) of the UCPA regarding the offense of bribing foreign public officials (defined in Article 18).

1. Increased Penalties for Individuals:

- The maximum penalties for individuals convicted of foreign bribery have been doubled.

- Imprisonment: Increased from a maximum of 5 years to 10 years (Revised UCPA Art. 21(4)(iv)). This places foreign bribery among the most serious economic crimes under Japanese law in terms of potential prison sentences.

- Fines: Increased from a maximum of JPY 5 million to JPY 30 million (Revised UCPA Art. 21(4)(iv)). This JPY 30 million ceiling matches the highest level of fines applicable to individuals for other major economic offenses in Japan.

- The law retains the possibility of imposing both imprisonment and a fine. Given the OECD's criticism of past sentencing practices (lack of combined penalties, suspended sentences), the significant increase in maximum penalties suggests an expectation of more severe sentencing in future cases, potentially including unsuspended prison terms and substantial fines, especially in egregious cases.

2. Increased Penalties for Corporations (Dual Liability):

- When an individual (director, agent, employee, etc.) commits foreign bribery in relation to the business of a corporation, the corporation itself can be held liable under the "dual liability" provisions (両罰規定, ryōbatsu kitei).

- The maximum fine imposable on corporations has been more than tripled, rising from JPY 300 million to JPY 1 billion (approximately USD 6-7 million, depending on exchange rates) (Revised UCPA Art. 22(1)(i)). This elevates the potential corporate penalty for foreign bribery to the highest level available under Japanese law, matching penalties for severe violations of financial regulations or antitrust laws.

- This dramatic increase reflects the OECD's concern that previous corporate fines were insufficient to deter bribery, especially by large multinational enterprises, and might not adequately reflect the often substantial economic benefits derived from corrupt practices.

3. Extended Statute of Limitations:

- As a direct consequence of increasing the maximum prison term for individuals to 10 years, the statute of limitations (公訴時効, kōso jikō) for prosecuting foreign bribery offenses (against both individuals and corporations) automatically extends from 5 years to 7 years (Revised UCPA Art. 22(3), applying Article 250(2)(iv) of the Code of Criminal Procedure).

- This addresses the OECD's concern that the previous 5-year period might be inadequate for the complexities of investigating transnational bribery cases, which often involve lengthy processes of gathering evidence across borders and international legal assistance.

4. Expanded Extraterritorial Jurisdiction (Covering Foreign Employees Acting Abroad):

- This is arguably the most impactful change from a compliance perspective for multinational companies.

- Previous Scope: Japan previously asserted jurisdiction over foreign bribery based on:

- Territoriality: Acts committed (in whole or part) within Japan.

- Nationality: Acts committed outside Japan by Japanese nationals.

- The "Loophole": This left a gap where a non-Japanese employee, working for a Japanese company (or its foreign subsidiary/branch) entirely outside Japan, could bribe a foreign official without triggering Japanese jurisdiction, provided no part of the act occurred in Japan and no Japanese national was directly involved as a co-conspirator whose actions could be prosecuted under the nationality principle.

- The New Provision (Art. 21(11)): The 2023 amendment adds a new subsection explicitly extending the application of the foreign bribery prohibition (specifically Article 21(4)(iv)) to non-Japanese nationals who commit the offense outside Japan if they are acting as a "director, agent, employee or other personnel" (代表者、代理人、使用人その他の従業者, daihyōsha, dairinin, shiyōnin sonohoka no jūgyōsha) of a Japanese juridical person (defined as a juridical person having its principal office in Japan) in connection with the business of that juridical person.

- Closing the Gap: This provision directly targets the scenario highlighted by the OECD. It means that a foreign employee of a Japanese company (or potentially its overseas branch, depending on interpretation) bribing a foreign official in a third country can now be prosecuted under Japanese law, even if the entire act takes place outside Japan and involves no Japanese nationals.

- Corporate Liability: Importantly, when such a foreign employee commits bribery abroad under circumstances covered by the new Art. 21(11), the employing Japanese corporation can also be prosecuted under the dual liability provision (Art. 22(1)(i)) and face the increased JPY 1 billion maximum fine.

Implications for Multinational Corporations

These amendments significantly raise the stakes for anti-bribery compliance for any company with substantial connections to Japan.

- Heightened Compliance Risk: The combination of drastically increased penalties and expanded jurisdiction means the potential legal and financial consequences of foreign bribery violations linked to Japanese operations are much more severe. Compliance failures are significantly more costly.

- Critical Need to Cover Foreign Personnel: Compliance programs must now rigorously address the risks posed by all personnel acting on behalf of a Japanese entity globally, irrespective of their nationality or location. Training, due diligence, and monitoring efforts need to effectively reach foreign employees in overseas subsidiaries and branches, as their actions abroad can now directly lead to prosecution in Japan for both the individual and the parent company.

- Scrutiny of Third-Party Agents: The term "agent" (代理人, dairinin) under the dual liability provisions is interpreted broadly and does not necessarily require a formal agency contract under civil law. Companies must exercise extreme caution regarding third-party intermediaries (agents, consultants, brokers, distributors) acting on their behalf overseas, as bribes paid by these third parties could potentially trigger liability for the Japanese corporation if sufficient oversight was lacking. Robust third-party due diligence and management are more critical than ever.

- Strengthening Compliance Programs: While Japan does not have a formal system akin to the US Department of Justice's guidance on effective compliance programs leading to potential declinations or reduced penalties in FCPA cases, the existence and effectiveness of a company's internal controls and compliance efforts are generally considered by prosecutors and courts in assessing corporate culpability and determining appropriate sanctions under the dual liability provisions. The 2023 amendments implicitly increase the pressure on companies to implement and maintain truly effective, risk-based anti-bribery programs covering their global operations. Elements typically expected include top-level commitment, risk assessments, clear policies and procedures, training, third-party management, confidential reporting mechanisms, and internal investigations.

- Increased Likelihood of Enforcement?: While legislative changes alone do not guarantee increased enforcement, the strengthening of the legal framework, driven by international pressure, suggests a potential for more active investigation and prosecution of foreign bribery cases by Japanese authorities in the future.

Unaddressed Issues

Despite the significant strengthening of the law, the 2023 amendments did not adopt all measures discussed during the preceding policy debates or recommended internationally. Notably:

- Fine Calculation: The OECD had suggested allowing fines based on the value of the bribe or the illicit profits gained. Japan retained a system based on statutory maximum fines, opting not to introduce a "profit disgorgement" or multiplier-based fine calculation method, citing difficulties in defining and calculating such amounts.

- Formal Leniency/Cooperation Mechanisms: Unlike the US system, Japan did not introduce a specific, formalized program offering leniency (like deferred prosecution agreements or non-prosecution agreements) in exchange for self-reporting, cooperation, and remediation in foreign bribery cases. While cooperation is likely considered informally, the lack of a structured system reduces certainty for companies contemplating disclosure.

Conclusion: A New Era of Anti-Bribery Enforcement in Japan

The 2023 amendments to the foreign bribery provisions of Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act mark a pivotal moment. By substantially increasing penalties to levels comparable with other major economies and, most importantly, expanding jurisdiction to cover foreign employees acting abroad for Japanese companies, Japan has significantly strengthened its legal arsenal against transnational corruption.

This signals a clear intent to address past criticisms and enhance enforcement efforts. For multinational corporations with a presence in Japan, whether as parent companies, subsidiaries, or partners, the message is clear: the risks associated with foreign bribery have increased significantly. A thorough review and reinforcement of global anti-bribery compliance programs, ensuring they effectively address the conduct of all employees and agents worldwide acting for or on behalf of Japanese entities, is now not just best practice, but a critical necessity to navigate this new and more stringent enforcement landscape.

- Japan’s Overseas Anti-Corruption Stance: Compliance Roadmap for US Companies

- Beyond Borders: Germany’s Supply-Chain Act & Mandatory Human-Rights Due Diligence

- Employer Duty of Care in Japan: Protecting Expatriate Staff During Crises

- METI – 2024 UCPA Amendment Outline (Japanese PDF)

- MOJ / Prosecutors Office – Foreign-Bribery Enforcement Statistics (Japanese)