Japan Overhauls Family Law: Introducing Joint Custody and Reforming Child Support

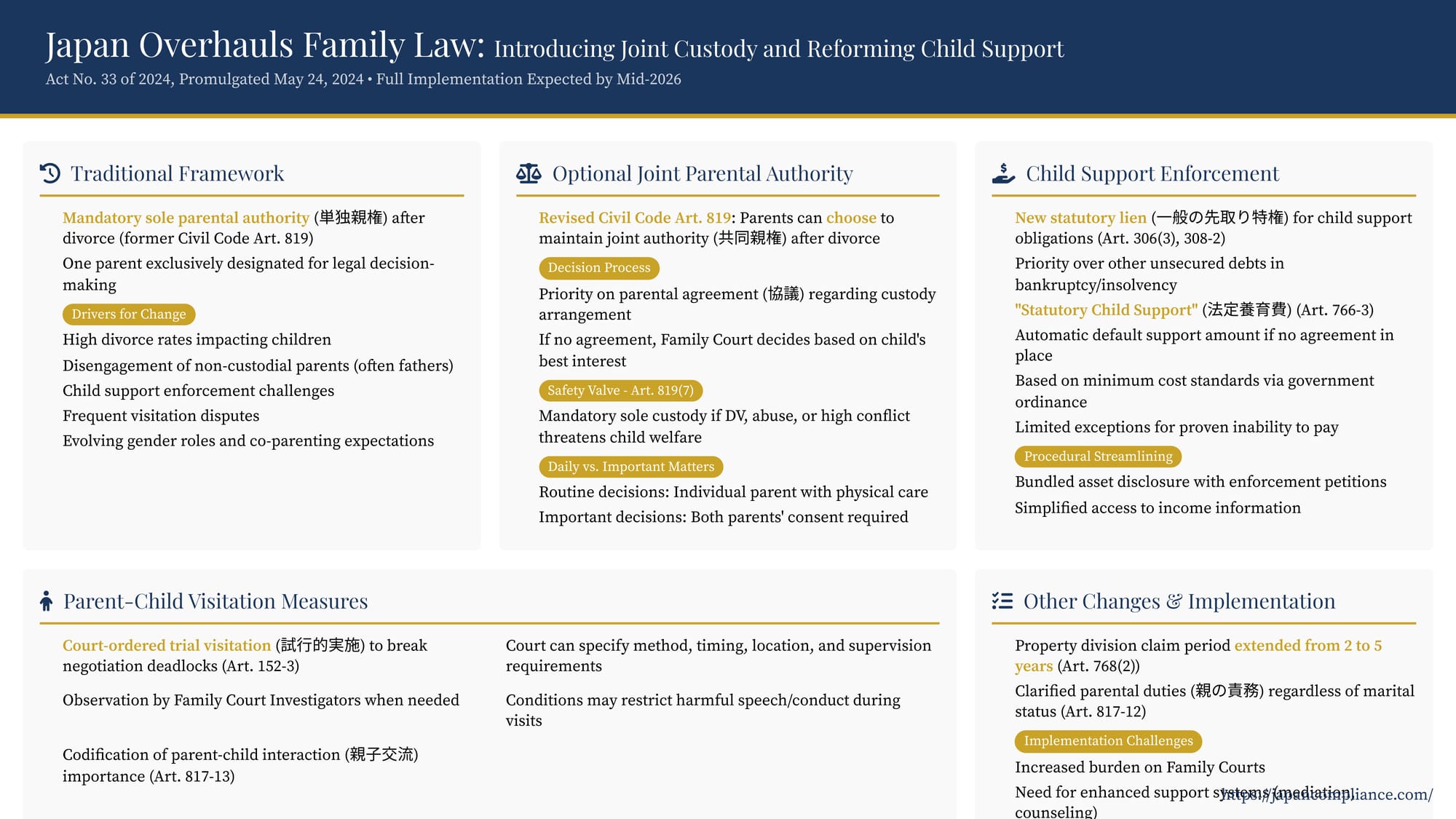

TL;DR: Japan’s 2024 family-law overhaul ends mandatory sole custody, lets parents choose joint parental authority, toughens child-support enforcement with statutory liens and “automatic” minimum payments, and expands tools for visitation. Full roll-out by mid-2026 will reshape divorce practice, court workloads, and workplace policies for parents.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background: The Traditional Framework and Drivers for Change

- A Paradigm Shift? Introducing Optional Joint Parental Authority

- Strengthening Child Support (Youikuhi) Enforcement

- Facilitating Parent-Child Visitation/Contact (Oyako Kouryuu)

- Other Significant Changes

- Implementation Challenges and Societal Impact

- Conclusion

Introduction

Family law systems around the world are continuously adapting to reflect evolving societal norms, changing family structures, and a growing focus on the best interests of children during parental separation or divorce. In a landmark move, Japan enacted a major overhaul of its Civil Code and related laws concerning family matters in May 2024 (Act No. 33 of 2024, promulgated May 24, 2024). This significant reform package introduces fundamental changes, most notably shifting away from mandatory sole parental authority after divorce to allow for the possibility of joint parental authority (often termed joint custody internationally) and implementing new measures aimed at strengthening child support enforcement and facilitating parent-child contact.

While these reforms primarily impact personal family relationships, their significance extends broadly. For international businesses operating in Japan, understanding major shifts in family law can provide crucial context regarding the social environment, potential impacts on employees navigating divorce or separation, and evolving societal expectations around parental roles and responsibilities. This article provides an overview of the key changes introduced by Japan's 2024 family law reform, explaining the shift towards optional joint custody, the new child support mechanisms, and other notable adjustments, ahead of the law's full implementation (expected by mid-2026).

1. Background: The Traditional Framework and Drivers for Change

To appreciate the magnitude of the 2024 reform, it's essential to understand the system it replaces. Following World War II, Japan abolished its pre-war patriarchal ie (household) system and adopted principles of gender equality. However, in the context of divorce, the post-war Civil Code mandated that parents must designate one parent to hold sole parental authority (tandoku shinken) over minor children (former Civil Code Art. 819). This mandatory sole custody regime stood in contrast to the joint custody arrangements common in many Western countries.

Over the decades, this system faced growing scrutiny and calls for reform driven by various factors:

- High Divorce Rates: Japan, like many developed nations, experiences significant numbers of divorces involving minor children.

- Ensuring Child Welfare: A desire to better reflect the principle of the "best interests of the child" (ko no rieki) by potentially allowing for continued legal involvement of both parents after divorce, where appropriate.

- Non-Custodial Parent Involvement: Concerns about the disengagement of non-custodial parents (most often fathers under the previous system) from their children's lives after divorce.

- Child Support Enforcement Issues: Persistently low rates of child support (youikuhi) payment by non-custodial parents, contributing to financial hardship, particularly for single mothers.

- Visitation Disputes: Frequent conflicts regarding parent-child visitation or contact (oyako kouryuu) arrangements.

- Evolving Societal Norms: Changing views on gender roles, fatherhood, and co-parenting.

- International Comparisons: Increasing awareness of joint custody models prevalent in other countries.

These factors fueled a long, complex, and often highly polarized debate about revising the post-divorce custody system, culminating in the 2024 legislative overhaul.

2. A Paradigm Shift? Introducing Optional Joint Parental Authority

The most widely discussed element of the reform is the introduction of optional joint parental authority (kyoudou shinken) after divorce.

- The Core Change (Revised Civil Code Art. 819): The previous mandatory sole custody rule is abolished. Instead, divorcing parents (whether divorcing by mutual agreement or through court proceedings) can choose to retain joint parental authority. If they agree on joint authority, it continues post-divorce. This option is also extended, by agreement or court order, to parents of children born outside of marriage (upon legal recognition, ninchi).

- Decision-Making Process:

- Parental Agreement Prioritized: The law emphasizes parental consultation (kyougi) and agreement as the preferred method for deciding between joint or sole authority (Art. 819(1)).

- Court Intervention: If parents cannot agree, either party can petition the Family Court (katei saibansho) to determine parental authority. The court will decide whether to assign sole authority (to one parent) or joint authority based on the best interests of the child (Art. 819(2), (5)).

- The Crucial "Safety Valve" Against DV and Abuse (Art. 819(7)): A critical component, added to address widespread concerns voiced during the legislative debate, is a mandatory exception. The Family Court must assign sole parental authority if it finds that, due to domestic violence (DV), child abuse, or other circumstances, one parent poses a risk of harm to the child's physical or mental well-being, or if joint exercise is otherwise deemed difficult (e.g., due to intractable conflict negatively impacting the child). This provision aims to prevent joint custody from being imposed in situations where it could endanger a child or perpetuate abuse.

- Exercise of Joint Parental Authority (Revised Civil Code Arts. 824-2, 824-3): How does joint authority function day-to-day?

- Daily Matters: Decisions concerning routine daily care and education (nichijou no koui) can generally be made individually by the parent who is physically caring for the child at that time (Art. 824-2(2)).

- Important Matters: Significant decisions (e.g., major medical treatments, choosing higher education, consenting to adoption, potentially relocation depending on circumstances) require the joint consent of both parents (Art. 824-2(1)).

- Urgent Circumstances: If there is an urgent need for the child's benefit, one parent can act unilaterally (Art. 824-2(1)(iii)).

- Disagreements: If parents with joint authority cannot agree on an important matter, either can petition the Family Court. The court can then designate one parent to exercise authority regarding that specific matter (Art. 824-3). This avoids dissolving the entire joint authority arrangement over a single disagreement.

- Designated Custodian (Kangosha): Even under joint parental authority, parents will typically need to determine the child's primary residence and day-to-day care arrangements. They can designate one parent as the primary custodian (kangosha) (Revised Civil Code Art. 824-2(3)).

This move to optional joint custody represents a fundamental shift in Japanese family law, potentially enabling greater continued involvement of both parents after divorce, but relying heavily on parental cooperation or court intervention guided by the child's best interests and safety.

3. Strengthening Child Support (Youikuhi) Enforcement

Addressing the chronic problem of unpaid child support was another major focus of the reform.

- The Problem: Japan has long struggled with low compliance rates for child support payments, often leaving custodial parents (predominantly mothers) facing financial instability. Enforcement mechanisms were often seen as cumbersome or ineffective.

- New Statutory Lien (Ippan no Sakidori Tokken) (Revised Civil Code Art. 306(3), 308-2): The reform grants a general statutory lien (a type of preferred claim) for child support obligations, up to a "standard amount" to be determined by government ordinance (based on standard living costs). This gives child support arrears higher priority over other unsecured debts if the paying parent becomes insolvent or enters bankruptcy proceedings, increasing the likelihood of recovery.

- "Statutory Child Support" (Houtei Youikuhi) (Revised Civil Code Art. 766-3): This entirely new mechanism aims to provide immediate baseline support. If parents divorce without having an agreement or court order for child support in place, the parent primarily caring for the child can automatically claim a statutorily defined monthly amount from the other parent, starting from the month after divorce.

- Purpose: To prevent a gap in support while parents negotiate or await a court decision, and to establish a minimum floor.

- Calculation: The amount will be calculated based on factors like the minimum cost of living for a child and parental capacity, with details set by government ordinance.

- Debtor's Defense: The paying parent can object to paying the full statutory amount if they can prove inability to pay (e.g., due to illness or unemployment) or that payment would cause them undue hardship. The court can then adjust or waive the amount.

- Procedural Streamlining: Amendments to the Civil Execution Act and Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act aim to make enforcement easier. Key changes include allowing creditors (custodial parents) to bundle requests for debtor asset disclosure (e.g., bank accounts, employment information) with the initial enforcement petition (Revised Civil Execution Act Art. 167-17, 193(2)), and potentially simplifying access to income information through court orders (Revised Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act Art. 152-2).

These measures collectively aim to make child support obligations more secure and easier to enforce.

4. Facilitating Parent-Child Visitation/Contact (Oyako Kouryuu)

The reforms also seek to promote continued contact between children and both parents after separation, where appropriate and safe.

- Codifying Importance of Contact: The revised Civil Code now explicitly mentions considering parent-child interaction (kouryuu) when determining custody arrangements, acknowledging its general importance for the child's welfare (Art. 817-13).

- Court-Ordered Trial Visitation (Shikouteki Jisshi) (Revised Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act Art. 152-3): Recognizing that disputes over visitation can become intractable, the law introduces a new tool for the Family Court. During proceedings concerning custody or visitation, the court can now order or encourage trial periods of visitation under specific conditions, provided it's not deemed harmful to the child's well-being and is necessary for the court's investigation.

- Purpose: To help break negotiation deadlocks, allow the court to observe interactions, assess the feasibility and safety of contact arrangements, and gather information before making a final order.

- Conditions: The court can specify the method, timing, location, and crucially, whether supervision by a third party (like a visitation support organization) or observation by a court official (Family Court Investigator) is required. The court can also impose conditions like prohibiting harmful speech or conduct during the visits.

- Feedback: The court can require parties to report on the outcomes of the trial visitation.

This mechanism provides courts with a more proactive tool to manage high-conflict visitation disputes while prioritizing child safety.

5. Other Significant Changes

- Property Division (Zaisan Bunyo) Time Limit: The period for claiming division of marital property after divorce is extended from two years to five years (Revised Civil Code Art. 768(2)). This addresses situations where financial matters are complex or take longer to resolve. The factors courts should consider when determining property division are also clarified (Art. 768(3)).

- Clarification of Parental Duties (Oya no Sekimu) (Revised Civil Code Art. 817-12): New provisions explicitly state the fundamental duties of parents towards their children, including respecting the child's personality (jinkaku sonchou), providing care and education appropriate to their age and development, and providing financial support necessary for the child to maintain a standard of living equivalent to the parent's. Importantly, these duties apply regardless of the parents' marital status, reinforcing the principle that parental responsibilities endure beyond divorce.

6. Implementation Challenges and Societal Impact

While the legal framework is now in place, the success of these reforms hinges on effective implementation and broader societal adaptation.

- Awaiting Full Implementation: The law allows up to two years from promulgation (i.e., until mid-2026) for the main provisions, including joint custody, to come into effect. This period is needed for the government to finalize crucial details through Cabinet Orders and Ministry Ordinances (e.g., the standard amount for statutory child support, detailed criteria for court decisions) and for systems to be prepared.

- Burden on Family Courts: The introduction of joint custody and new procedures is expected to increase the complexity and potentially the volume of cases handled by Japan's already strained Family Courts. Adequate resources, specialized training for judges and mediators, and potentially new case management approaches will be essential.

- Need for Enhanced Support Systems: Making optional joint custody viable, especially in cases with moderate conflict, requires robust support infrastructure. This includes accessible and affordable mediation services, parental counseling programs, neutral third-party supervised visitation centers, and legal aid for low-income parents. The availability and quality of these services vary across Japan and require significant investment.

- Rigorous Application of Safeguards: The effectiveness of the "safety valve" provisions (mandating sole custody in DV/abuse cases) is paramount. Courts and related agencies need reliable methods for screening for abuse and ensuring victim safety is prioritized in all custody and visitation decisions. Coordination between courts, police, and child welfare agencies is vital.

- Cultural Shift and Public Education: Moving from a long-standing tradition of sole custody requires a shift in societal understanding and expectations regarding post-divorce parenting. Public education campaigns explaining the new options, emphasizing cooperative co-parenting (where appropriate), and clarifying parental responsibilities will be important. Whether the reforms lead to more collaborative parenting or simply new forms of conflict remains to be seen.

- Implications for Employers and Employees: While seemingly distant from the corporate world, these fundamental changes in family law can have ripple effects. Employees undergoing divorce may need time off for new court procedures or mediation. Joint custody arrangements could necessitate more flexible work schedules or shared leave requests. Changes to child support rules might impact employees' financial situations. Employers may benefit from understanding the basics of the new system to support employees navigating these transitions.

Conclusion

Japan's 2024 family law reform constitutes a watershed moment, fundamentally altering the legal landscape for divorce and child-rearing. The introduction of optional joint parental authority marks a departure from the mandatory sole custody system that defined the post-war era, potentially fostering greater continued involvement from both parents. Simultaneously, measures to strengthen child support enforcement and facilitate parent-child contact aim to address long-standing challenges related to the financial and emotional well-being of children after parental separation.

The reforms embody a complex balancing act – attempting to promote shared parental responsibility while safeguarding children from conflict and abuse. The success of this ambitious overhaul will depend critically not just on the letter of the law, but on the robust development of judicial guidelines, adequate court resources, comprehensive support services for families, and a societal willingness to embrace more cooperative approaches to co-parenting when it is safe and beneficial for the child.

For international observers and businesses, these changes offer a window into evolving social norms and legal frameworks in Japan. While the direct impact on corporate operations may be limited, understanding this significant societal shift provides valuable context for engaging with employees and navigating the broader social environment in Japan as the new law moves towards full implementation by mid-2026.