Is a "Mujina" a "Tanuki"? How a 1925 Japanese Hunting Case Defined Criminal Intent

Decision Date: June 9, 1925

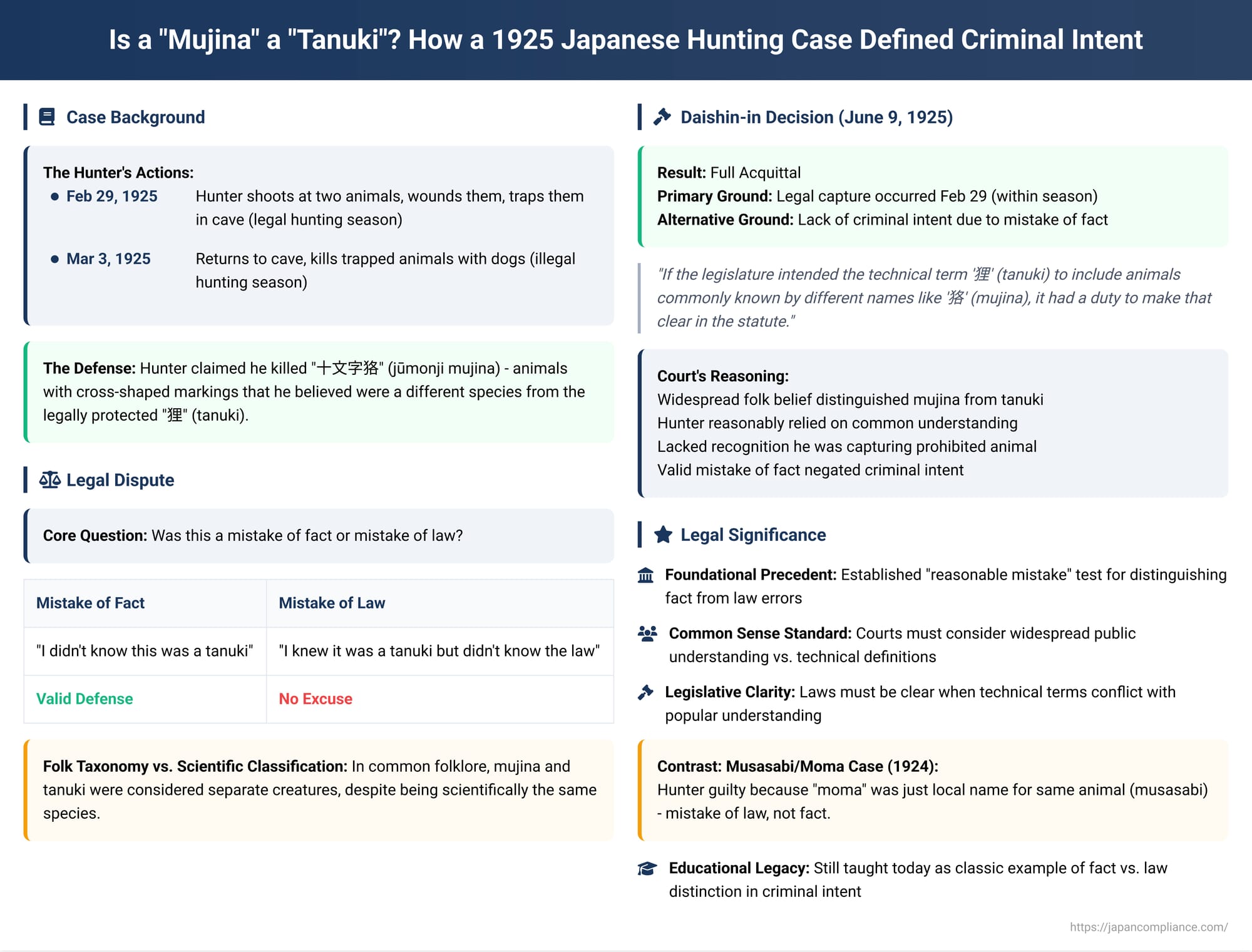

The distinction between a mistake of fact and a mistake of law is a foundational concept in criminal law. A mistake of fact—for example, taking a coat you genuinely believe is yours—can negate the intent required to be guilty of a crime. A mistake of law—for example, not knowing that taking someone else's coat is illegal—is famously no excuse. But this seemingly clear line can become blurry when a person's understanding of the world, shaped by common language and folklore, conflicts with the precise, technical language of a statute.

This very issue was at the heart of two classic, almost legendary, cases from 1920s Japan that are still used today to teach this fundamental legal distinction. The most famous of these is the "Tanuki/Mujina case," decided by Japan's pre-war high court, the Daishin-in, on June 9, 1925. In it, the court found that a hunter's zoological mistake, rooted in common folklore, was a legally valid error of fact that exonerated him of a crime.

The Factual Background: The Hunt for the "Jūmonji Mujina"

The case involved a licensed hunter and an interpretation of the Hunting Law of the era. The law prohibited the hunting of certain animals, including the 狸 (tanuki, or raccoon dog), outside of a designated season.

The hunter's actions unfolded in two stages:

- February 29 (during the legal hunting season): The defendant was hunting in a mountain forest when he spotted and shot at two tanuki. The wounded animals fled into a nearby cave. The hunter blocked the cave entrance with stones, effectively trapping them, and then returned home.

- March 3 (outside the legal hunting season): The hunter returned to the cave, removed the stones, and used his hunting dogs to enter the cave and kill the two animals inside.

Because the final killing occurred outside the legal season, the hunter was charged with violating the Hunting Law. His defense was a peculiar one: he argued that the animals he killed were not, in fact, the legally protected tanuki. He claimed that the animals had a distinct cross-shaped marking on their backs and were what the people in his region called 十文字狢 (jūmonji mujina), which he sincerely believed to be an entirely different species from the tanuki mentioned in the law.

The Daishin-in's Ruling: A Finding of No Intent

The Daishin-in issued a full acquittal. It first found, on a technical ground, that the legal "capture" of the animals was completed on February 29, when the hunter trapped them in the cave. Since that day was still within the legal hunting season, he was not guilty.

However, the Court then went on to address the hunter's more fascinating defense in a famous obiter dictum—a judicial statement that is not essential to the final holding but provides influential guidance. The Court stated that even if the capture were deemed to have occurred on the illegal date of March 3, the defendant would still be not guilty because he lacked the necessary criminal intent.

The Court's reasoning was a masterclass in legal pragmatism:

- It acknowledged that from a scientific, zoological perspective, the jūmonji mujina is simply a variety of tanuki.

- However, the Court gave great weight to the fact that in common Japanese custom and folklore, the tanuki and the mujina had long been popularly considered two distinct and separate creatures.

- The Court reasoned that if the legislature, in writing the law, intended the technical term

狸(tanuki) to also include the animal that the public commonly knew by a different name,狢(mujina), then it had a duty to make that clear in the text of the statute. - Since the law was not clear, the defendant was justified in relying on the common, popular understanding. Because he believed he was capturing a mujina—which, in his mind and in the common parlance of his community, was not a tanuki—he "lacked the recognition" that he was capturing the animal actually prohibited by the law.

This lack of recognition was deemed a valid error of fact, which negated his criminal intent and provided a second, independent ground for his acquittal.

The Crucial Counterpoint: The "Musasabi/Moma" Case

To fully appreciate the Court's reasoning, it is essential to contrast the "Tanuki/Mujina" case with its famous counterpart, which the Daishin-in had decided just a year earlier.

- The Facts: In that case, a hunter captured a

鼯鼠(musasabi), a species of giant flying squirrel that was protected under the Hunting Law. His defense was that he didn't know he had captured a musasabi; he claimed he thought he had captured aもま(moma). - The Ruling: The Daishin-in found this hunter guilty. The key difference was that, unlike tanuki and mujina, the word moma was not the name of a different creature in the popular imagination. It was simply a local, colloquial folk name for the exact same animal, the musasabi. The Court ruled that the hunter knew what the animal was—he knew it as a moma—and his mistake was simply not knowing that the law protected this animal under its formal name, musasabi. This was not an error about the factual nature of the animal, but an error about its legal status. It was, the court concluded, "mere ignorance of the law," which is no excuse.

Distinguishing Fact from Law: The "Reasonable Mistake" Test

Together, these two seemingly contradictory rulings create a remarkably clear legal test. The line between a legally valid mistake of fact and an invalid mistake of law hinges on the reasonableness of the defendant's misunderstanding from the perspective of an ordinary person at the time.

- In the Tanuki/Mujina case, the belief that the two were different creatures was a widespread and long-standing folk taxonomy. An ordinary person could reasonably make this mistake. Therefore, the hunter's mistake was treated as an error of fact. He did not recognize the object before him as possessing the essential, legally defined quality of being a "tanuki."

- In the Musasabi/Moma case, there was no widespread belief that these were different animals. The hunter correctly identified the animal he was capturing by its common name; his mistake was only about the law that applied to it. This was an error of law.

The "Tanuki/Mujina" ruling also carries an important lesson for lawmakers. When a legal term has a technical or scientific meaning that conflicts with a deeply ingrained popular understanding, the legislature must be explicit if it intends for the technical meaning to prevail. Without such clarity, citizens cannot be expected to know the law's true scope and cannot be justly punished for relying on the common sense of their community.

Conclusion: A Lesson in Common Sense and Legal Interpretation

The "Tanuki/Mujina" case, especially when read alongside its "Musasabi/Moma" counterpart, remains a cornerstone of Japanese legal education. Despite being a century old and revolving around a quirky zoological debate, the pair offers a timeless and profound lesson on the nature of criminal intent. They stand for the principle that the line between a mistake of fact and a mistake of law is not always a bright one and can depend on the social context and the reasonableness of the defendant's belief.

The rulings teach that a mistake about the identity of an object can be a legally valid error of fact if it is rooted in a widespread, common-sense public understanding that conflicts with a technical definition in a statute. A mistake about the legal status of an object that the defendant correctly identifies, however, is merely an error of law. The law does not demand scientific expertise from its citizens, but it does demand that they know the law. This pragmatic distinction ensures that criminal intent is not found where a genuine and reasonable misunderstanding of the world exists.