Iressa and the Duty to Warn: Japan's Supreme Court on Pharmaceutical Product Liability and Package Inserts

Judgment Date: April 12, 2013

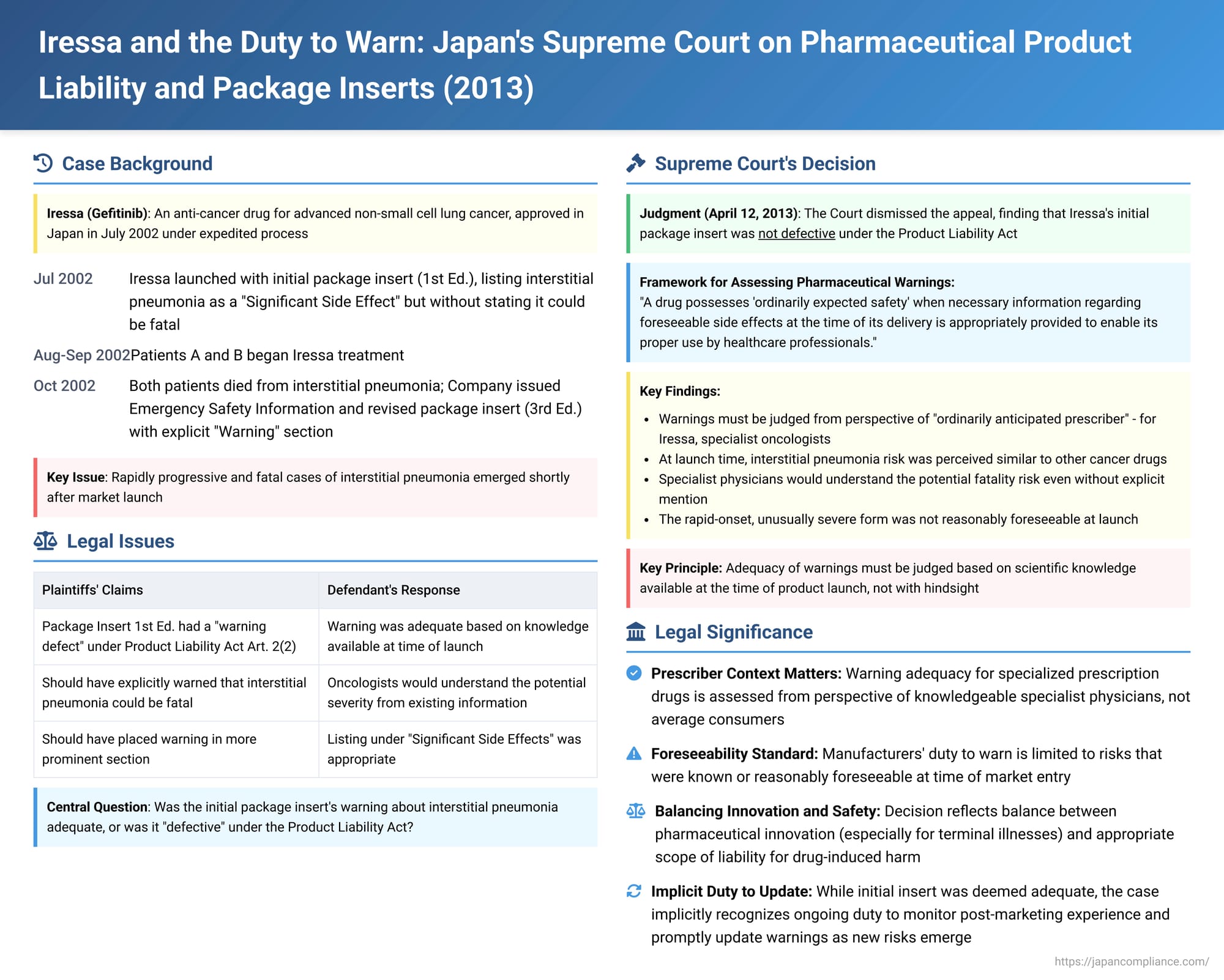

Pharmaceutical drugs offer immense benefits in treating diseases, but they also carry inherent risks of side effects. When these side effects are severe or even fatal, questions arise regarding the responsibility of the drug manufacturer. A crucial aspect of this responsibility lies in providing adequate warnings and instructions to healthcare professionals and patients. The "Iressa Litigation" in Japan, culminating in a Supreme Court judgment on April 12, 2013 (Heisei 24 (Ju) No. 293), delved deeply into the product liability of a pharmaceutical company concerning its anti-cancer drug Iressa, specifically focusing on whether the initial package insert provided adequate warning about the risk of a serious side effect, interstitial pneumonia.

Iressa: A New Hope for Lung Cancer, A Tragic Side Effect

Iressa (generic name: Gefitinib) is a molecular targeted therapy drug developed for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), particularly for patients with advanced or recurrent disease for whom standard chemotherapy had proven ineffective or was no longer an option. Given the often grim prognosis for such patients and the potential of Iressa to offer a new line of treatment, it underwent an expedited approval process in Japan. This process, common at the time for certain critical drugs like anti-cancer agents, allowed for approval based on the results of Phase II clinical trials, with the more extensive Phase III trial results to be submitted to regulatory authorities after the drug was already on the market. Y, the defendant company, received import approval for Iressa and began selling it in Japan on July 16, 2002.

However, shortly after its launch, a significant number of cases of interstitial pneumonia (間質性肺炎 - kanshitsusei haien), a serious lung condition, were reported as a side effect in patients treated with Iressa. Some of these cases progressed rapidly and were fatal.

The plaintiffs in this case, X1 and X2, were family members of two NSCLC patients, A and B, respectively. Patient A (stage IV NSCLC) began Iressa treatment in August 2002 and died in October 2002 from what was believed to be Iressa-induced interstitial pneumonia. Patient B (stage III NSCLC, with a pre-existing history of interstitial pneumonia that had somewhat worsened due to the cancer's progression) started Iressa in September 2002 and also died in October 2002 after an acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia. Both patients A and B were treated with Iressa during the period when the initial version of the drug's package insert was in use.

The Legal Battle: Allegations of a "Warning Defect" in the Initial Package Insert

X1 and X2 sued Y company under Japan's Product Liability Act (製造物責任法 - Seizōbutsu Sekinin Hō). Their central argument was that Iressa, as initially marketed, had a "defect" (欠陥 - kekkan) as defined in Article 2, Paragraph 2 of the Act. Specifically, they alleged a "warning/instruction defect" (指示・警告上の欠陥 - shiji/keikoku-jō no kekkan) in the first edition of Iressa's package insert (添付文書 - tenpu bunsho).

The key deficiencies alleged in the initial package insert (referred to as "Package Insert 1st Ed.") were:

- Interstitial pneumonia was listed as the fourth item under the "Significant Side Effects" (重大な副作用) section, rather than being highlighted in a separate "Warning" (警告) section at the top of the insert.

- The description stated: "Interstitial pneumonia (frequency unknown): Interstitial pneumonia may occur, so observe patients carefully, and if abnormalities are noted, discontinue administration and take appropriate measures."

- Crucially, Package Insert 1st Ed. did not explicitly state that interstitial pneumonia could be fatal.

It's important to note that following the emergence of numerous severe cases post-launch, Y company, under the guidance of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, issued an "Emergency Safety Information" bulletin on October 15, 2002. On the same day, Y revised the package insert (to its 3rd edition), which then included a prominent "Warning" section at the beginning. This revised insert and later versions contained much stronger language about the risk of acute lung disorder and interstitial pneumonia, explicitly stating that these conditions "can occur and may follow a fatal course," and advising close monitoring including regular chest X-rays. However, patients A and B had been treated before these revisions.

The Tokyo District Court (first instance) found that while Iressa did not have a "design defect," Package Insert 1st Ed. did have a "warning/instruction defect" due to its inadequate communication of the risks. It partially granted the plaintiffs' claims. The Tokyo High Court (second instance), however, overturned this, finding no defect in either the design or the warnings, and dismissed the plaintiffs' claims entirely. X1 and X2 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Framework for "Defect" in Pharmaceutical Warnings

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of April 12, 2013, ultimately dismissed the plaintiffs' appeal, finding that Iressa, as supplied with Package Insert 1st Ed., did not have a defect under the Product Liability Act. The Court laid out a detailed framework for assessing such claims:

- General Principle for "Defect" in Pharmaceuticals (Regarding Warnings/Instructions):

The Court started by acknowledging that pharmaceuticals, by their very nature (being foreign substances to the human body), inherently carry the risk of some side effects. The mere existence of side effects does not automatically render a drug defective.

Instead, a drug is considered to possess its "ordinarily expected safety" when necessary information regarding foreseeable side effects at the time of its delivery (i.e., when it is put into the market) is appropriately provided to enable its proper use by healthcare professionals. A "defect" can arise if such crucial information about side effects is not appropriately provided. - The Package Insert as the Key Information Vehicle for Prescription Drugs:

For prescription medicines like Iressa, the primary means of conveying this necessary side effect information to healthcare professionals is the package insert (添付文書). - Standard for Adequacy of Warnings in Package Inserts:

The adequacy of a package insert's warnings must be judged from the perspective of the "ordinarily anticipated prescriber or user" (通常想定される処方者ないし使用者 - tsūjō sōtei sareru shohōsha naishi shiyōsha) of the drug. For highly specialized medications such as Iressa—an anti-cancer agent indicated for advanced or recurrent NSCLC and designated as a "drug requiring physician's instruction" (要指示医薬品)—this means the target audience for the warnings is physicians specializing in the treatment of such cancers (oncologists).

The critical question is whether the risks of foreseeable side effects were made "sufficiently clear" to these specialist physicians. This determination requires a comprehensive consideration of all circumstances, including:- The content and severity of the side effect in question (including its frequency of occurrence).

- The level of knowledge and clinical capabilities generally possessed by such specialist physicians regarding the drug class, the disease, and potential adverse reactions.

- The form, style, and overall presentation of the side effect information within the package insert.

Applying the Framework to Iressa's Initial Package Insert

The Supreme Court then applied this framework to the specific facts concerning Iressa's Package Insert 1st Ed.:

- (A) Regarding the Generally Foreseeable Risk of Interstitial Pneumonia with Anti-Cancer Drugs:

The Court found that at the time of Iressa's import approval and launch in July 2002:- The available clinical trial data (domestic and international Phase II trials) indicated that Iressa carried a risk of inducing interstitial pneumonia, but this risk was perceived to be comparable in frequency and severity to that associated with other existing anti-cancer drugs. There were some fatal cases in overseas trials, but a direct causal link to Iressa was not definitively established due to confounding factors like co-administration of other chemotherapy or advanced disease.

- Specialist physicians treating advanced lung cancer (the intended prescribers of Iressa) were generally aware that interstitial pneumonia was a known, common, and potentially fatal side effect of many anti-cancer agents.

- Package Insert 1st Ed. did list interstitial pneumonia under the "Significant Side Effects" section. It also advised physicians to "observe patients carefully, and if abnormalities are noted, discontinue administration and take appropriate measures."

- The Supreme Court concluded that specialist oncologists, upon reading this information in Package Insert 1st Ed., and drawing upon their existing professional knowledge about anti-cancer drugs, would have understood that Iressa, like other drugs in its class, carried this risk of interstitial pneumonia, which could potentially be fatal. The Court stated that this understanding would not be materially affected by the specific order in which interstitial pneumonia was listed within the "Significant Side Effects" section, or by other information available in medical journals at the time.

- (B) Regarding the Unforeseen Aspect – Rapidly Progressing and Unusually Severe Interstitial Pneumonia:

The Court acknowledged that the specific pattern of some Iressa-induced interstitial pneumonia cases—characterized by rapid onset shortly after starting treatment and unusually severe, swift progression to fatality—was a feature that became more apparent through post-marketing surveillance and led to the Emergency Safety Information in October 2002.- This particularly aggressive form of interstitial pneumonia was not considered similar to the typically understood presentations of this side effect with other anti-cancer drugs.

- Crucially, the Court found that this specific, rapidly severe form could not have been reasonably foreseen based on the clinical trial data and other scientific information available to Y Company at the time of Iressa's import approval and initial marketing.

- The Court also considered the context: Iressa was approved under an expedited pathway for a very aggressive and often terminal illness (advanced/recurrent NSCLC) where existing treatment options were limited. Specialist physicians prescribing such a novel drug in such a context would generally understand that new and powerful medications approved based on Phase II data might carry as-yet-unknown or incompletely characterized risks.

- Therefore, the absence of warnings in Package Insert 1st Ed. specifically detailing this unforeseen, rapidly severe form of interstitial pneumonia did not render that initial insert inadequate or defective. A manufacturer cannot be held liable for failing to warn about a specific risk manifestation that was not scientifically foreseeable at the time the product was placed on the market.

- Conclusion on Defect: Based on this two-part analysis, the Supreme Court concluded that Package Insert 1st Ed. was not defective with respect to the side effects that were foreseeable at the time of Iressa's approval and launch. The Court also found no new circumstances emerging between the approval date and the time patients A and B began Iressa treatment that would have rendered the initial insert inadequate regarding then foreseeable risks.

Significance and Broader Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's decision in the Iressa litigation provides important, albeit debated, guidance on product liability for pharmaceuticals in Japan:

- High Bar for "Warning Defects" for Specialized Prescription Drugs: The ruling suggests a relatively high bar for establishing a "warning defect" under the Product Liability Act when the drug in question is a specialized prescription medicine intended for use by expert physicians. The Court gives considerable weight to the existing knowledge base and clinical judgment expected of those specialist prescribers.

- Foreseeability as a Key Element: The decision strongly underscores that a manufacturer's duty to warn about side effects is generally limited to those risks that were known or reasonably foreseeable based on the scientific and technical knowledge available at the time the product was marketed. This aligns with the concept of the "development risk defense" (PL Act Art. 4(i)), although the Court's primary analysis here was centered on whether a "defect" existed in the first place.

- The Package Insert Judged Against Contemporary Knowledge: The adequacy of warnings is judged based on the state of knowledge at the time of the product's launch, not with the benefit of hindsight gained from later post-marketing experience or research.

- Ongoing Duty to Monitor and Update (Implicit): While the case focused on the initial package insert, the sequence of events (rapid emergence of severe cases post-launch, followed by an Emergency Safety Information bulletin and revised inserts) implicitly highlights the ongoing duty of pharmaceutical companies to conduct post-marketing surveillance and to update warnings promptly as new significant risks become known. This was not the direct point of liability in this judgment but remains a critical aspect of pharmaceutical safety.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2013 Iressa judgment found that the initial package insert for the drug was not defective under Japan's Product Liability Act. The Court emphasized that for specialized prescription drugs, the adequacy of warnings about foreseeable side effects is assessed from the perspective of knowledgeable prescribing physicians. Risks or specific manifestations of side effects that were not reasonably foreseeable at the time of product launch do not retroactively render the initial warnings defective. While this decision provided a degree of legal clarity for pharmaceutical manufacturers concerning their duty to warn for complex medicines, it also generated considerable discussion and debate regarding the balance between pharmaceutical innovation, patient access to new treatments for severe diseases, and the appropriate scope of corporate responsibility for drug-induced harm.