IP Management for Startups & Universities in Japan: Protecting and Leveraging Innovation

TL;DR

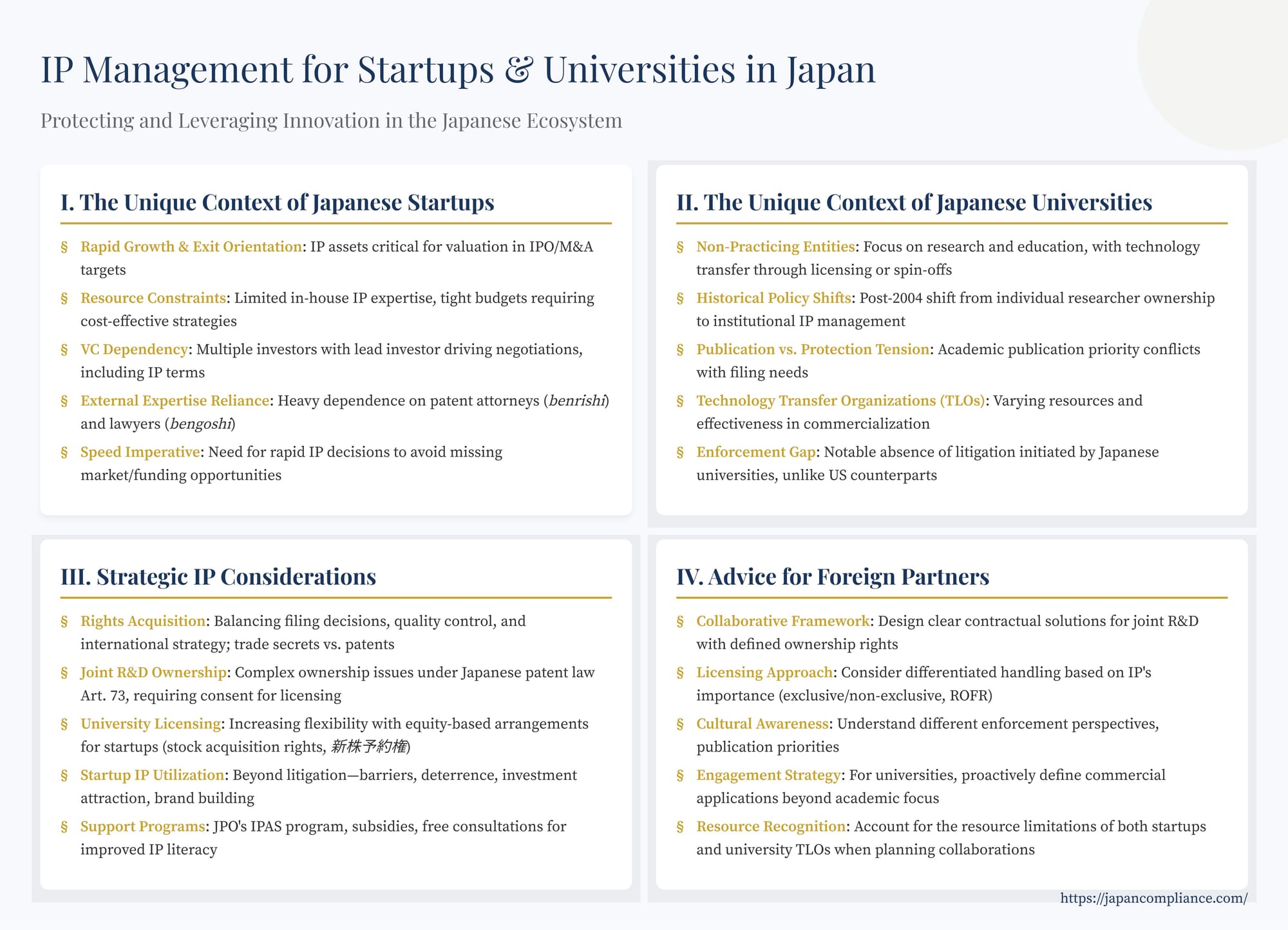

Explains how Japanese startups and universities can build cost-effective IP portfolios, navigate joint R&D ownership, and use patents, trade secrets and licensing to raise funds, strike partnerships and drive national innovation goals.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Engines of Japan's IP-Driven Growth

- Part 1: IP Management in Japanese Startups

- The Unique Context of Japanese Startups

- Strategy Formulation: Integrating IP from Day One

- Rights Acquisition: Navigating the Process

- Utilization: Beyond the Threat of Litigation

- Support Systems

- Part 2: IP Management in Japanese Universities

- The Unique Context of Japanese Universities

- Strategy Formulation: Bridging Research and Commercialization

- Joint R&D and IP Ownership: Navigating Complexity

- Rights Acquisition: Balancing Academia and Commerce

- Utilization: Licensing and the Enforcement Gap

- Conclusion: Strategic Imperatives for Innovation Partners

Introduction: The Engines of Japan's IP-Driven Growth

Japan's strategic focus on becoming an "Intellectual Property Nation" relies heavily on the innovative capacity of its startups and universities. These entities are crucial sources of new technologies, business models, and creative content. However, effectively managing intellectual property (IP) within these dynamic environments presents unique challenges distinct from those faced by established corporations. Startups operate under intense pressure for rapid growth and funding, often with limited internal IP expertise. Universities, while centers of research, grapple with translating academic discoveries into commercially viable assets and navigating the complexities of technology transfer and industry collaboration. Understanding the specific IP management considerations for both Japanese startups and universities is essential for foreign companies seeking to invest, partner, or license technology in Japan's innovation ecosystem.

Part 1: IP Management in Japanese Startups

The startup landscape in Japan, while growing robustly in recent years with increased funding activity (particularly in sectors like SaaS and AI), operates under specific constraints that heavily influence IP strategy.

The Unique Context of Japanese Startups

Several factors shape how Japanese startups approach IP:

- Rapid Growth Cycles & Exit Orientation: Most startups aim for significant growth within a limited timeframe, targeting an Initial Public Offering (IPO) or Merger & Acquisition (M&A) as an exit strategy. IP assets play a critical role in company valuation and attractiveness during these events.

- Venture Capital Dependency: Funding primarily comes from venture capital (VC) firms and corporate venture capital (CVC). Investment rounds often involve multiple investors, with a "lead investor" typically driving negotiations on terms, including IP-related clauses. This leaves individual investors, especially non-lead foreign entities, with limited negotiating leverage on standard investment agreements.

- Resource Constraints: Startups almost invariably lack dedicated in-house IP departments or personnel, particularly in the early stages. IP budgets are often tighter compared to larger companies, necessitating cost-effective strategies.

- Speed of Execution: The startup environment demands rapid decision-making. Lengthy internal approval processes for IP filings or licensing deals can be detrimental, potentially causing a startup to miss crucial funding or market opportunities.

Strategy Formulation: Integrating IP from Day One

Effective IP management for startups begins with integrating IP considerations into the core business strategy from the outset, rather than treating it as an afterthought.

- Early Integration: Because startups often create new markets or niches, their strategy frequently involves educating the market and building barriers to entry against fast followers. An IP strategy must align with this. For example, a startup developing a novel material might need to disclose some technology to encourage adoption but use patents to control key aspects and enable licensing revenue as the market grows. This requires parallel planning of business, development, and IP strategies.

- Leveraging External Expertise: Given the lack of internal IP staff, startups heavily rely on external experts – primarily patent attorneys (benrishi, 弁理士) and lawyers (bengoshi, 弁護士). Choosing the right advisors is crucial. Effective advisors need not only IP knowledge but also an understanding of the startup industry, business acumen to contribute to strategic discussions, and the willingness to grasp the startup's technology. Programs like the JPO-backed Intellectual Property Acceleration program for Startups (IPAS) recognize this, forming support teams of business and IP experts to assist startups.

- Tailored Approach: IP strategy isn't one-size-fits-all. It must be tailored to the startup's specific business model, technology, competitive landscape, and exit goals. While patents are often emphasized, trade secrets, trademarks, design rights, and copyrights all have roles to play depending on the context.

Rights Acquisition: Navigating the Process

Securing IP rights presents practical challenges for resource-constrained startups.

- Filing Decisions: Startups, often lacking experience, may struggle to evaluate the necessity and strategic value of filing specific patents suggested by external counsel. The fee structures of some external counsel (e.g., success fees upon grant) might introduce biases towards filing or narrowing claims excessively during prosecution, which startups may not be equipped to critically assess. Engaging separate counsel for second opinions or using advisors with fee structures not directly tied to filing/grant outcomes can mitigate these risks.

- Quality Control: Drafting high-quality patent specifications that align with the business strategy requires significant input and review. Startups may lack the internal capacity for thorough quality checks on drafts prepared by external counsel. Close collaboration and clear communication are essential.

- International Strategy: For startups with global ambitions, deciding where and when to file internationally is a critical, costly decision requiring careful strategic alignment.

- Trade Secrets vs. Patents: Deciding what to patent and what to keep as a trade secret is a key strategic choice, balancing the benefits of exclusive rights against the risks of disclosure and the costs of patenting.

Utilization: Beyond the Threat of Litigation

While the ability to sue infringers is a core benefit of IP, startups often lack the resources for protracted litigation. However, IP utilization extends far beyond lawsuits.

- Building Barriers & Deterrence: Patents can create significant barriers for potential competitors, particularly other startups. Even without litigation, the existence of relevant patents can deter entry or, strategically, disrupt a competitor's funding round. Communicating the existence of core patents to the investor community (e.g., VCs) can create pressure, as investors have a fiduciary duty to avoid funding ventures with high infringement risk. This may force competitor startups to seek legal opinions or delay their funding, giving the original startup a valuable time advantage.

- Attracting Investment & Partnerships: A strong IP portfolio signals technological capability and defensibility, making a startup more attractive to investors and potential corporate partners. IP due diligence is a standard part of investment rounds and M&A.

- Licensing Revenue: As discussed, licensing core technology can be a viable strategy, especially in market-creation scenarios, allowing the startup to maintain some control while fostering broader adoption.

- Branding & Marketing: Trademarks are crucial for brand building. Design rights can protect the aesthetic appeal of products. Even patents can be used in marketing materials to convey innovation and technological leadership.

- Strategic Disclosure/Non-Assertion: Sometimes, selectively not asserting patents or contributing them to standards can foster industry collaboration or build goodwill, which can be strategically advantageous.

Startups must be purposeful about why they are acquiring each IP right and actively pursue utilization strategies aligned with those goals to maximize the return on their limited IP investments.

Support Systems

Recognizing these challenges, Japanese government bodies and related organizations offer various support programs. The JPO and INPIT provide resources like IPAS, free consultations, seminars, and subsidies for patent filing, particularly targeting SMEs and startups. These programs aim to improve IP literacy and provide access to expert advice.

Part 2: IP Management in Japanese Universities

Japanese universities are vital sources of basic research and cutting-edge discoveries. However, translating this research into societal and economic value through effective IP management involves a different set of challenges compared to startups or established companies.

The Unique Context of Japanese Universities

- Non-Practicing Entities: Universities typically do not commercialize their inventions directly. Their primary role is research and education, with technology transfer occurring through licensing or the creation of spin-off companies. This influences their perspective on IP value and enforcement.

- Historical Context & Policy Shifts: Historically, especially before the incorporation of national universities in 2004, IP rights from university research often vested in individual professors rather than the institution. Policies like the "Japanese Bayh-Dole Act" (Act on Special Measures for Industrial Revitalization, 1999) and subsequent initiatives promoted university ownership and the establishment of IP management offices and TLOs to facilitate technology transfer. However, challenges in effective commercialization persist.

- Balancing Publication and Protection: Academic culture prioritizes rapid publication of research findings, which can conflict with the need to file patent applications before public disclosure. Managing this tension is a constant operational challenge.

- Resource Allocation: While university IP offices and TLOs exist, their resources, expertise, and strategic focus can vary significantly between institutions. Surveys like the University Technology Transfer Survey track activities but highlight ongoing needs for skilled personnel and operational funding.

Strategy Formulation: Bridging Research and Commercialization

Universities face the inherent difficulty of developing commercially relevant IP strategies without direct involvement in the market implementation of their technologies.

- Aligning Research with Needs: Identifying research with commercial potential and shaping it towards market needs often requires proactive engagement with industry, which can be challenging given differing timelines and objectives.

- Marketing University IP: Effectively marketing university IP portfolios to potential licensees (both established companies and startups) requires translating complex scientific discoveries into understandable value propositions. Utilizing platforms like Japan Search or engaging with VCs and industry associations can help, but requires dedicated effort and communication skills tailored to non-experts.

- Industry Collaboration Models: Joint research projects with industry are crucial but require careful negotiation regarding IP ownership and usage rights. Universities must balance the company's need for commercial advantage with the university's mission of broader knowledge dissemination and potential future research avenues.

Joint R&D and IP Ownership: Navigating Complexity

Collaborations between universities and industry often lead to jointly created inventions, raising complex ownership and exploitation issues.

- Ownership Models: While joint ownership is common, it can create hurdles for licensing and transfer under Japanese patent law, which generally requires consent from all co-owners for licensing (Patent Act, Article 73(3)) or assignment of a share (Article 73(1)). In some cases, assigning sole ownership to the university (with appropriate licenses back to the company) might be preferable for facilitating broader dissemination, though this requires careful negotiation considering the company's contribution. Conversely, assigning sole ownership to the company might stifle further academic research or wider use.

- Contractual Solutions: Collaboration agreements must clearly define how IP arising from the project will be owned and managed. Recent guidance suggests frameworks that differentiate handling based on the IP's importance to the company's core business, including options like exclusive licenses (potentially converting to non-exclusive if not worked), rights of first refusal (ROFR), or options for the company to secure exclusive rights within a defined period. Clear definitions of terms like "reasonable period" or "justifiable reason" for non-working are critical to avoid future disputes. Standard agreement templates exist but often require customization.

- Researcher Mobility: IP ownership issues also arise when researchers move between institutions, requiring clear institutional policies and potentially complex negotiations between universities.

Rights Acquisition: Balancing Academia and Commerce

The patenting process itself requires strategic considerations within the university context.

- Timing and Disclosure: The pressure to publish necessitates careful coordination with patent filings. Filing provisional or domestic applications before publication is standard practice, but the content must be sufficient to support commercially valuable claims later. Relying solely on academic papers for patent drafts can lead to overly narrow claims focused on specific experimental results rather than broader, commercially relevant applications.

- Scope and Commercial Value: University IP offices and external counsel need to work with researchers to broaden the scope of inventions beyond the immediate research findings, considering potential commercial applications and alternative embodiments to create stronger, more valuable patents. Utilizing priority periods effectively to incorporate feedback from potential industry partners identified post-filing can enhance commercial relevance.

- International Filing: Decisions on international patent protection require strategic assessment of market potential and licensing opportunities, balanced against significant costs.

Utilization: Licensing and the Enforcement Gap

Universities primarily utilize IP through licensing and spin-off creation.

- Licensing Strategies: Agreements vary widely. For licenses to startups, universities are increasingly open to flexible arrangements, potentially accepting equity or warrants (stock acquisition rights, 新株予約権) in lieu of or in addition to traditional cash royalties (upfront fees, running royalties). This aligns incentives and addresses the cash constraints of early-stage companies. Determining the appropriate royalty rate or equity percentage requires careful consideration of the IP's contribution to the business. Precedent exists for major Japanese universities successfully using equity-based licensing deals.

- Technology Transfer Organizations (TLOs): Approved TLOs, either internal or external to the university, play a crucial role in managing IP, marketing technologies, negotiating licenses, and supporting spin-offs. Their effectiveness varies based on resources, expertise, and networks.

- The Enforcement Challenge: A significant difference compared to the US is the notable absence of IP litigation initiated by Japanese universities. While US universities actively enforce their patents, sometimes generating substantial revenue, Japanese universities have historically been hesitant. This reluctance can weaken their negotiating position in licensing discussions, as potential licensees may perceive a lower risk of being sued for infringement. Recent government guidelines encourage universities to consider enforcement, including litigation, as a necessary tool to protect the value of their IP and ensure responsible utilization, but a cultural shift may be needed for this to become common practice.

Conclusion: Strategic Imperatives for Innovation Partners

Both startups and universities are indispensable players in Japan's IP-driven innovation strategy. Startups require nimble, business-aligned IP management that leverages limited resources effectively, using IP not just for defense but for growth, funding, and market positioning. Universities face the challenge of bridging the gap between academic research and commercial application, requiring strategic handling of IP ownership in collaborations, proactive licensing efforts, and a potentially evolving stance on enforcement.

For foreign companies looking to engage with these entities – whether through investment, R&D collaboration, or technology licensing – understanding these distinct contexts, challenges, and the supporting ecosystem is paramount. Acknowledging the resource constraints of startups, the unique mission of universities, the nuances of joint IP development, and the available government support mechanisms will enable more effective partnerships and successful navigation of Japan's dynamic intellectual property landscape.