Invisible Losses? Japanese Supreme Court on Damages for Lost Earning Capacity Without Actual Income Drop

Date of Judgment: December 22, 1981

Case Name: Claim for Damages

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

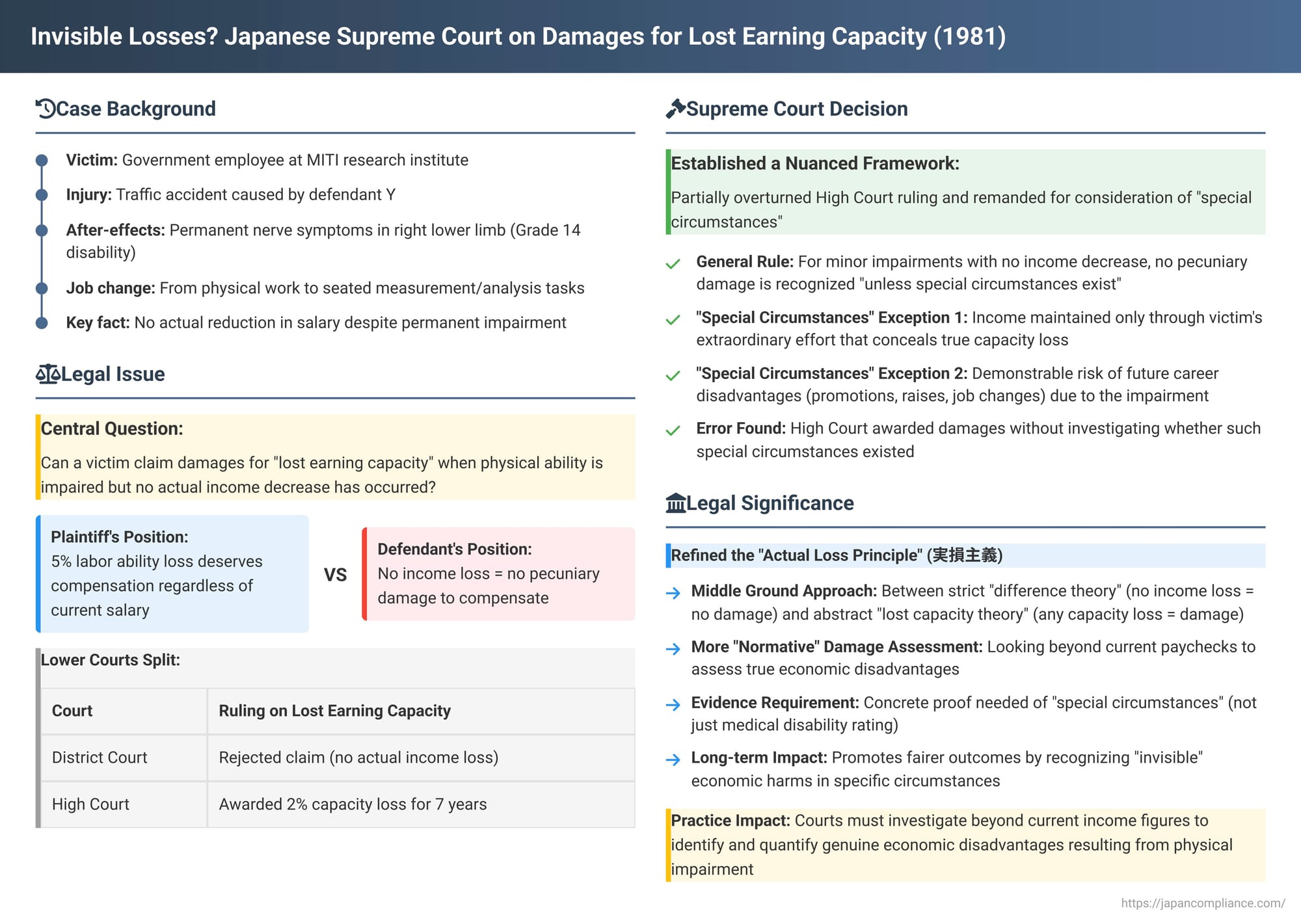

When an individual suffers a personal injury due to someone else's wrongful act (a tort), one of the key components of their damage claim is often for "lost earning capacity." This typically refers to the income they will lose in the future because their ability to work has been diminished by the injury. But what happens if a person sustains a permanent impairment, yet their actual salary or income doesn't decrease after the accident? Can they still claim financial compensation for a theoretical or underlying loss of their ability to earn, even if it's not immediately reflected in their paychecks? A significant Japanese Supreme Court decision from December 22, 1981, addressed this complex issue, establishing important guidelines for when such "invisible losses" might be legally compensable.

An Accident, A Lingering Injury, But No Pay Cut: The Facts

The case involved a government employee injured in a traffic accident:

- The Accident and Injuries: X, a technical officer working at a research institute of the former Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), was injured when struck by a car driven by Y. X underwent medical treatment for approximately two years and ten months.

- Permanent After-Effects: While X recovered from the acute injuries, he was left with permanent after-effects (後遺症 - kōishō). These consisted of local nerve symptoms in his right lower limb. Medically, this was classified as a Grade 14 physical disability (a relatively lower grade on the disability scale). Importantly, the diagnosis indicated no functional impairment or movement disorder in his upper or lower limbs.

- Impact on Work and Income:

- Due to the lingering pain and discomfort in his lower limb, X found it difficult to continue with his previous job duties, which involved physically demanding plastic molding processing work. As a result, his work responsibilities were changed to measurement and analysis tasks, which could largely be performed while seated.

- Despite this change in duties and the persistence of his symptoms, X did not suffer any actual reduction in his salary or any other disadvantageous treatment in terms of his pay from his government employer following the accident.

- The Lawsuit and X's Claim for Lost Earning Capacity: X sued Y (the driver responsible for the accident) for damages. In addition to claims for medical expenses and solatium (慰謝料 - isharyō, compensation for pain, suffering, and emotional distress), X sought compensation for "lost earning capacity" (逸失利益 - isshitsu rieki). X argued that his permanent after-effects equated to a 5% loss of his overall labor ability and claimed a sum equivalent to 5% of his annual income projected over a period of 34 years (his expected remaining working life), totaling over ¥2.38 million.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The first instance court acknowledged X's after-effects but stated that it was "difficult to recognize that a future income reduction will occur for X due to this loss of labor ability from the after-effects." It concluded that while X's job change and any workplace difficulties due to the after-effects should be considered when calculating the solatium (for non-pecuniary harm), a separate award for pecuniary loss of earning capacity could not be granted because no actual income loss was demonstrated.

- The High Court (on appeal) took a different approach. It held that if a victim is recognized as having suffered a total or partial loss of labor ability due to an accident, then even if there is no observable decrease in their income, it is still appropriate for the court to assess and quantify the damage. This assessment should comprehensively consider factors such as the victim's pre- and post-injury income levels, their type of occupation, and the site and severity of their after-effects. Based on this reasoning, and by referencing labor ministry tables that correlate disability ratings with percentage loss of labor capacity, the High Court found that X had suffered a 2% loss of labor ability for a period of 7 years following the accident. It accordingly awarded X over ¥340,000 for this lost earning capacity as a pecuniary loss, in addition to a sum for solatium.

Y (the defendant driver) appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, specifically challenging the award of damages for lost earning capacity in the absence of any actual income reduction.

The Supreme Court's Nuanced Approach

The Supreme Court, on December 22, 1981, partially overturned the High Court's decision. It found that the High Court's award for lost earning capacity had been made prematurely and remanded the case for further examination of whether specific "special circumstances" existed that would justify such an award despite the lack of an actual income drop.

The Supreme Court laid out the following key principles:

- General Rule – No Actual Income Loss, No Pecuniary Damage for Minor Impairment:

- The Court started by acknowledging that, hypothetically, the loss of some physical functionality itself due to an accident's after-effects could be conceived as a form of "damage" (損害 - songai).

- However, if the degree of these after-effects is "relatively minor" (比較的軽微 - hikakuteki keibi), AND

- Considering the nature of the victim's occupation, no present or future reduction in income is apparent or recognized,

- THEN, as a general rule, and "unless special circumstances exist" (特段の事情のない限り - tokudan no jijō no nai kagiri), there is no basis for recognizing pecuniary damage specifically for partial loss of labor ability.

- The "Special Circumstances" Exception – When Pecuniary Damage Can Be Recognized Despite No Income Loss:

The Supreme Court then elaborated on what might constitute such "special circumstances" that would allow a court to award pecuniary damages for lost earning capacity even if the victim's paychecks haven't changed:- (a) Income Maintained by Victim's Special Efforts: If the victim's income has remained unchanged not because their earning capacity is truly unaffected, but because they are making "special efforts" (特別の努力 - tokubetsu no doryoku) to overcome the limitations imposed by their injury and thereby prevent an income decrease. In such a scenario, if it can be recognized that their income would have decreased without these extraordinary efforts or other non-accident-related factors (like a sympathetic employer temporarily maintaining salary despite reduced productivity), then a pecuniary loss due to impaired capacity can be acknowledged.

- (b) Tangible Risk of Future Disadvantage: Even if the current loss of labor capacity is assessed as minor, if the nature of the victim's current occupation, or an occupation they are reasonably expected to pursue in the future, is such that there is a demonstrable risk of disadvantageous treatment specifically concerning promotions, salary raises, opportunities for job changes (転職 - tenshoku), etc., due to the permanent after-effects, then this can constitute a cognizable economic disadvantage.

- In essence, the Court stated that for pecuniary damages for lost earning capacity to be awarded in the absence of actual income loss, there must be proof of special circumstances sufficient to affirm a real "economic disadvantage" (経済的不利益 - keizaiteki furieki) brought about by the after-effects, going beyond the mere existence of the physical impairment.

- High Court's Error: The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred. It had awarded damages for lost earning capacity based solely on the existence of X's after-effects (and a standardized disability rating) without adequately investigating or determining whether such "special circumstances" – like extraordinary effort by X or a clear risk of future career detriment directly attributable to the 2% assessed capacity loss – were actually present.

The case was therefore sent back to the High Court for a re-examination of these specific points.

Defining "Damage" in Personal Injury: Beyond Actual Pay Slips

This 1981 Supreme Court decision is significant for refining the "actual loss" principle (実損主義 - jitsuson shugi), which traditionally underpins damage calculations in Japanese tort law.

"Lost Earning Capacity" vs. "Lost Income"

- The Traditional "Difference Theory" (差額説 - sagaku setsu): For pecuniary damages, this theory primarily focuses on the actual monetary difference in the victim's financial position before and after the tort. Applied strictly, if a victim's income does not decrease, then there is no pecuniary loss under this heading. Some earlier Supreme Court cases had applied this quite strictly.

- The "Lost Earning Capacity Theory" (労働能力喪失説 - rōdō nōryoku sōshitsu setsu): This alternative theory, which X (the plaintiff) argued from, posits that the impairment or loss of a person's inherent ability to work and earn a livelihood is itself a distinct form of damage, regardless of whether that loss immediately translates into a smaller paycheck. For example, a homemaker whose ability to perform household chores is impaired suffers a loss of valuable (though unpaid) labor capacity. Similarly, a young person's future earning potential can be diminished by an injury, even before they have established a career.

- The Supreme Court's Compromise: The 1981 judgment carves out a middle ground. It does not fully embrace the abstract notion that any diagnosed loss of physical capacity automatically equates to a pecuniary loss if there's no actual income drop. However, it moves decisively away from a rigid "no income drop equals no pecuniary damage" stance by introducing the "special circumstances" exception. This allows courts to look beyond the immediate paycheck to more subtle or future economic disadvantages.

Towards a More "Normative" Damage Assessment

Legal commentators suggest that this decision marked a step towards a more "normative" understanding of damages (規範的損害論 - kihanteki songai ron). This means that the assessment of loss isn't just a mechanical calculation of actual income differences but also involves an evaluation of the fairness of the situation and the true nature of the disadvantages imposed on the victim by the injury. The "special circumstances" – such as the need for extraordinary effort to maintain income, or the risk of future career stagnation – are factors that allow a court to recognize a compensable pecuniary loss even when current income figures alone might not show it.

Proving "Special Circumstances"

Demonstrating these "special circumstances" requires concrete evidence. For instance, a plaintiff might need to show:

- Evidence of specific efforts made to overcome their disability at work that go beyond what would normally be expected.

- Proof that a promotion was denied or a less favorable job assignment was given due to the impairment.

- Expert testimony or industry data suggesting that individuals with similar impairments in their profession typically face quantifiable disadvantages in career progression or earning potential over time.

Simply having a medical disability rating or experiencing some level of physical discomfort might not be sufficient if it doesn't translate into a proven or highly probable future economic detriment in their specific line of work.

Conclusion

The 1981 Supreme Court ruling provides a nuanced and more equitable approach to claims for lost earning capacity in Japanese personal injury law. It acknowledges that a physical impairment resulting from a tort doesn't always lead to an immediate and obvious drop in income. However, it also recognizes that a loss of labor capacity can still represent a real and compensable economic harm if the victim is forced to exert extraordinary efforts to maintain their income level or if they face a tangible and demonstrable risk of future career setbacks or earning disadvantages due to their injury. This decision encourages a holistic assessment of damages, looking beyond just current paychecks to the broader and longer-term economic implications of a lasting impairment caused by another's wrongful act, thereby promoting a fairer outcome for victims under specific, well-defined circumstances.