Investing in Japanese Startups: Key Legal Considerations for US Investors

TL;DR

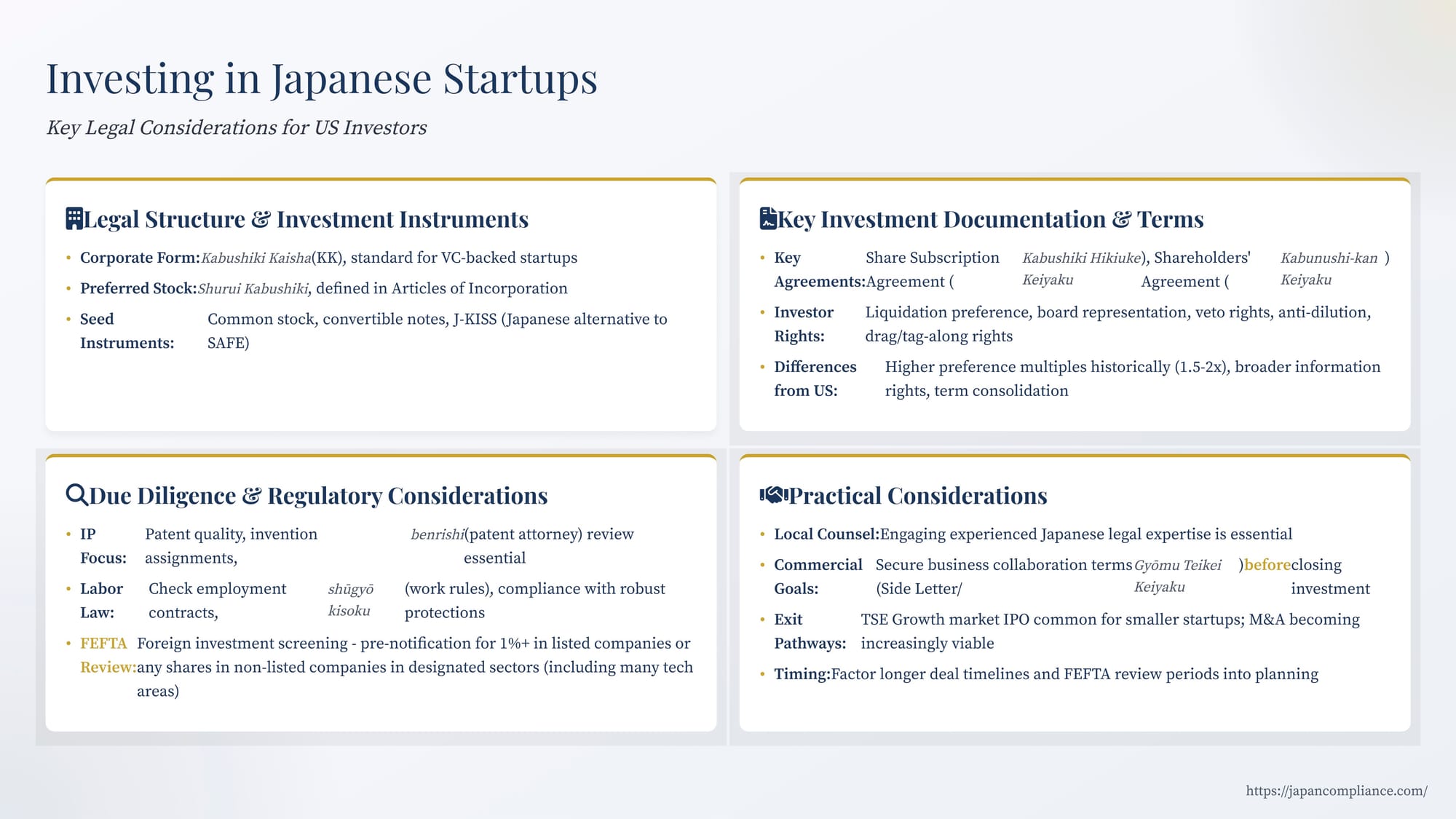

Most Japanese startups are KKs that issue preferred stock similar to U.S. deals, but term sheets, FEFTA filings, and board structures differ. U.S. investors should watch liquidation multiples, veto scopes, and national-security reviews while securing side-letter business rights up front.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Why Japan’s VC Scene Matters

- Legal Structures & Funding Instruments

- Core Deal Documents in Japan

- Preferred Stock Terms vs. Silicon Valley Norms

- Due-Diligence Hotspots (IP, Labor, Compliance)

- Foreign Investment Review under FEFTA

- Governance & Minority-Protection Snapshot

- Side Letters for Strategic Investors

- Exit Paths: TSE Growth vs. M&A

- Practical Tips & Timelines

- Conclusion

Introduction: Tapping into Japan's Innovation Engine

Japan's startup ecosystem, long overshadowed by Silicon Valley and other global hubs, is experiencing significant growth and attracting increasing attention from international investors. Fueled by government initiatives aimed at fostering innovation, deep pools of technological expertise, and a large domestic market, Japanese startups present compelling opportunities, particularly in sectors like SaaS, AI, deep tech, and life sciences.

However, for US investors accustomed to the deal structures, legal documentation, and regulatory environment of Silicon Valley, investing in Japan requires navigating a distinct landscape. While sharing fundamental concepts like venture capital funding and equity rounds, Japanese startup investment involves different corporate forms, standard contract terms, regulatory hurdles, and cultural nuances. Understanding these key legal considerations is crucial for structuring successful investments and building fruitful partnerships with Japanese innovators.

This article outlines critical legal aspects US investors should be aware of when considering investments in Japanese startups, covering corporate structures, investment instruments, typical agreement terms, due diligence priorities, regulatory reviews, and exit strategies.

Legal Structure & Investment Instruments

- Corporate Form: The overwhelming majority of Japanese startups destined for growth and external investment are incorporated as Kabushiki Kaisha (株式会社, often abbreviated as KK). This is the standard Japanese stock corporation structure, analogous to a US C-corp. While other forms exist (like the Gōdō Kaisha or GK, similar to an LLC), the KK structure is preferred for venture funding and eventual IPOs. Establishing a KK has become relatively straightforward, with minimum capital requirements significantly lowered since the early 2000s.

- Investment Instruments:

- Preferred Stock (種類株式 - Shurui Kabushiki): Similar to US practice, venture capital investments in Series A rounds and beyond typically involve preferred stock. Japanese corporate law allows for various classes of shares with different rights regarding dividends, liquidation preferences, and voting, which are defined in the company's Articles of Incorporation (定款 - Teikan). While the concept is similar, the specific terms common in Japan can differ from Silicon Valley norms (discussed below).

- Seed Stage Instruments: For seed funding, investments might be made using common stock, preferred stock, or increasingly, convertible instruments. While traditional convertible notes exist, Simple Agreements for Future Equity (SAFEs), popularized by Y Combinator in the US, are less common in Japan compared to convertible notes or specific Japanese variations like J-KISS (Japanese Keep It Simple Security), which aims to provide a SAFE-like instrument adapted to Japanese law. Convertible Equity (CE), which converts based on time or milestones rather than just a future financing round, is also sometimes used.

Key Investment Documentation & Terms

Unlike the common US practice (particularly following NVCA models) where investment terms are spread across multiple documents (Stock Purchase Agreement, Investor Rights Agreement, Voting Agreement, Right of First Refusal & Co-Sale Agreement), Japanese startup investments typically consolidate terms into two main agreements:

- Share Subscription Agreement (株式引受契約 - Kabushiki Hikiuke Keiyaku): This agreement covers the specifics of the share issuance – the number of shares, price per share, payment mechanics, closing conditions, and often contains representations and warranties from the company and founders, along with potential indemnification provisions or investor call options triggered by breaches.

- Shareholders' Agreement (株主間契約 - Kabunushi-kan Keiyaku): This is the cornerstone document outlining the ongoing rights and obligations among the company, founders, and investors post-investment. It typically governs key investor protection provisions.

While specific terms are always subject to negotiation, US investors should be aware of common practices and potential differences from US standards regarding key rights typically found in the Shareholders' Agreement:

- Liquidation Preference: Preferred shareholders usually receive priority in distributions upon a liquidation event (including M&A, often termed "deemed liquidation" - みなし清算 minashi seisan). While a 1x non-participating preference is common in the US, Japanese deals historically saw higher multiples (1.5x or 2x) and participating preferred stock (where investors get their preference plus a pro-rata share of remaining proceeds alongside common stock) was more common. However, market trends are shifting, and terms closer to US standards (like 1x non-participating or participating with a cap) are becoming more prevalent, though negotiation is still key.

- Information Rights: Access to financial statements and business updates is standard. However, the level of detail and frequency might differ. Unlike the common US distinction where only "Major Investors" meeting a certain threshold get extensive rights, information rights in Japan are often negotiated more broadly within the Shareholders' Agreement, though significant investors naturally have more leverage.

- Board Representation: Obtaining a board seat (director - 取締役 torishimariyaku) or observer rights (オブザーバー) is a common goal for lead investors or those making substantial investments. The specific threshold for these rights is negotiated. Japanese corporate law generally requires a minimum of three directors for a KK with a board. Minority investors often secure appointment rights contractually in the Shareholders' Agreement.

- Veto / Consent Rights (Protective Provisions): Investors typically seek veto rights over critical corporate actions to protect their investment. Under the Companies Act (会社法 - Kaisha Hō), certain fundamental changes (e.g., amending Articles of Incorporation, mergers, significant asset sales) already require a special resolution at a shareholders' meeting (typically a two-thirds supermajority), giving investors holding over one-third of voting rights a de facto veto. Additionally, Japanese law allows for issuing specific classes of shares with built-in veto rights over defined matters (requiring approval at a meeting of that class). More commonly, specific veto rights (e.g., over new share issuances diluting the investor, changes to preferred rights, large debt incurrence, deviation from budget, executive compensation changes) are contractually defined in the Shareholders' Agreement, triggered by approval requirements from preferred shareholders or specific investor-appointed directors. The scope of these contractual vetoes is a key negotiation point.

- Anti-Dilution Protection: Protection against dilution from subsequent down-rounds is standard, typically using a weighted-average formula, similar to US practice. Full-ratchet protection is less common.

- Preemptive Rights (優先引受権 - Yūsen Hikiuke Ken): The right to maintain pro-rata ownership by participating in future financing rounds is usually included, though its scope and mechanics might be negotiated.

- Exit Rights:

- Drag-Along Rights (強制売却権 - Kyōsei Baikyaku Ken): Enables majority shareholders (often including major investors) to force minority shareholders to sell their shares in a qualifying M&A transaction approved by a defined threshold. This ensures 100% of the company can be delivered to a buyer. Thresholds and conditions are negotiated.

- Tag-Along / Co-Sale Rights (売却参加権 - Baikyaku Sanka Ken): Protects minority shareholders by allowing them to participate on a pro-rata basis if founders or major shareholders sell their shares.

- Registration Rights: Provisions granting investors rights to have their shares registered for sale in an IPO are common, similar to US practice, though the specifics relate to Japanese listing rules.

- Founder Vesting & Lock-ups: Provisions ensuring founder shares vest over time and restrictions on founder share transfers are standard practice, often detailed in the Shareholders' Agreement or separate founder agreements.

Due Diligence Considerations in Japan

While the core principles of due diligence (DD) are universal, investing in Japan requires attention to specific local factors:

- Intellectual Property: For technology startups, IP DD is paramount. This involves not just confirming patent filings or registrations but assessing patent quality, scope, enforceability, and freedom-to-operate (FTO) within the Japanese market and key international markets. Understanding the startup's IP strategy (patent vs. trade secret) and ensuring proper assignment of inventions from employees/founders is crucial. Engaging Japanese patent attorneys (benrishi) early is advisable.

- Labor & Employment: Japan has robust labor laws offering significant employee protections. DD should verify compliance with regulations regarding working hours, overtime pay, social insurance contributions, and dismissal procedures. Reviewing employment agreements and work rules (就業規則 - shūgyō kisoku) is essential. Ensuring proper handling of confidentiality and invention assignments in employment contracts is also critical.

- Regulatory Compliance: Depending on the startup's industry (e.g., FinTech, HealthTech, Energy), specific regulatory licenses, permits, or approvals may be required. Verifying compliance with relevant Japanese laws (e.g., data privacy under the Act on the Protection of Personal Information - APPI, financial regulations, pharmaceutical affairs law) is critical.

- Corporate Governance: Reviewing the Articles of Incorporation (Teikan), corporate registration (Tōki), board minutes, and shareholder meeting minutes is necessary to confirm proper governance and authorization for past actions, including previous financing rounds.

- Financial & Tax: Standard financial and tax DD applies, but understanding specific Japanese accounting standards and tax implications is important.

Regulatory Landscape: Foreign Investment Review (FEFTA)

US investors must be aware of Japan's foreign investment screening regime under the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (FEFTA, 外国為替及び外国貿易法 - Gaitamehō). While historically less stringent than CFIUS in the US, FEFTA regulations were significantly tightened in recent years, particularly concerning national security.

- Scope: FEFTA requires foreign investors acquiring shares in Japanese companies to file notifications with the government (via the Bank of Japan).

- Pre-Notification Requirement: A pre-transaction notification and approval are required if a foreign investor acquires 1% or more of the shares/voting rights in a listed company operating in designated sensitive sectors, or acquires any shares in a non-listed company operating in such sectors.

- Designated Sectors: The list of designated sectors requiring pre-notification is broad and includes areas relevant to national security, public order, public safety, and the smooth operation of the Japanese economy. Crucially, this includes many sectors common for tech startups, such as:

- Core Sectors: Weapons, aircraft, nuclear, space, cybersecurity, semiconductors, advanced electronics, critical minerals, certain medical devices/pharmaceuticals.

- Other Designated Sectors: Software development, data processing, internet services, telecommunications, electricity, gas, oil, water supply, railways, maritime/air transport, agriculture, fisheries, leather manufacturing, security services.

- Exemptions: Exemptions from pre-notification exist, particularly for portfolio investments or where the foreign investor meets certain criteria (e.g., agreeing not to appoint board members or access sensitive non-public technology information), but these must be carefully assessed. For non-listed startups in designated sectors, exemptions are generally not available for direct share acquisitions.

- Post-Transaction Reporting: Even if pre-notification is not required, a post-transaction report is generally necessary for acquisitions exceeding certain thresholds (typically 10% for listed companies, but applies to any acquisition for non-listed).

- Review Process & Timeline: Pre-notification triggers a review by the Ministry of Finance and relevant sector-specific ministries. There is a statutory 30-day waiting period after formal filing, although pre-consultation with ministries is common and the review period can be shortened or extended. This regulatory timeline must be factored into deal planning.

Given the breadth of designated sectors, particularly in technology, foreign investors targeting Japanese startups must assess FEFTA requirements early in the process. Failure to comply can result in corrective orders or penalties.

Corporate Governance Snapshot

While a Shareholders' Agreement provides contractual controls, the underlying Japanese Companies Act framework is also relevant:

- Shareholder Meetings (株主総会 - Kabunushi Sōkai): Ordinary resolutions typically require a simple majority of votes present; special resolutions (for major changes like amending the Articles, M&A) generally require attendance by shareholders holding a majority of voting rights and approval by two-thirds of the votes present.

- Board of Directors (取締役会 - Torishimariyaku-kai): Directors owe fiduciary duties (duty of care - 善管注意義務 zenkan chūi gimu; duty of loyalty - 忠実義務 chūjitsu gimu) to the company. Investor-appointed directors must act in the company's best interest, not solely the investor's.

- Minority Protections: The Companies Act provides certain statutory rights for minority shareholders (e.g., rights to inspect records, call meetings, propose actions, derivative suits), though thresholds vary.

Business Collaboration and Side Letters

For corporate venture capital (CVC) investors or strategic partners, the investment is often primarily motivated by potential business synergies (access to technology, distribution channels, joint development). As investment agreements focus mainly on shareholder rights, securing these business objectives requires separate, concurrent negotiation.

Consistent with practice when investing in US startups, these commercial arrangements are typically documented in a Side Letter or a separate Business Alliance Agreement (業務提携契約 - Gyōmu Teikei Keiyaku) executed alongside the investment documents. It is critical to negotiate and finalize these commercial terms before or simultaneous with the investment closing. Relying on post-closing negotiation often fails, as the startup's incentive to prioritize the collaboration diminishes once funding is secured.

The Exit Environment

Understanding potential exit paths is vital for investors:

- IPO: Japan has active markets for smaller growth companies, notably the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) Growth market (formerly Mothers). Listing requirements focus on growth potential, liquidity (share distribution, market cap), and having at least one year of continuous operation. While IPOs are a common exit route, median market capitalizations at listing for startups have historically been lower than on Nasdaq, though some large successful startup IPOs occur.

- M&A: Strategic acquisitions are becoming an increasingly important exit path for Japanese startups. Both domestic corporations and foreign companies are active acquirers. The prevalence of drag-along rights in investment agreements facilitates M&A exits.

Practical Considerations

- Local Counsel: Engaging experienced Japanese legal counsel (lawyers for corporate/contracts/FEFTA, benrishi for IP) is indispensable. They provide expertise on local law, market practices, and negotiation dynamics.

- Cultural Nuances: Decision-making processes in Japanese companies can be more consensus-driven and may take longer than in some US contexts. Understanding communication styles and building relationships is important.

- Deal Timelines: While improving, deal execution timelines can sometimes be longer than in Silicon Valley, partly due to regulatory reviews like FEFTA and potentially more deliberative internal processes within Japanese startups or VCs.

Conclusion: Navigating with Local Expertise

Investing in Japanese startups offers access to a vibrant and technologically advanced innovation ecosystem. However, success requires more than just identifying promising targets; it demands a thorough understanding of Japan's specific legal and regulatory framework. Key differences from US practice exist in standard investment documentation, common deal terms (especially regarding preferred stock rights and investor controls), foreign investment review processes under FEFTA, and aspects of corporate governance and exit pathways.

US investors should prioritize early engagement with experienced Japanese legal and IP counsel, conduct thorough, locally-informed due diligence, factor regulatory timelines into their planning, and proactively negotiate critical terms, including business collaboration objectives via Side Letters. By appreciating the unique aspects of the Japanese startup environment and leveraging local expertise, foreign investors can effectively navigate the legal landscape and capitalize on the significant opportunities within Japan's growing venture ecosystem.