Inventing Fairness: Japan's Olympus Case and "Reasonable Remuneration" for Employee Inventions

The innovation driven by employees is a cornerstone of corporate success, particularly in technology-intensive industries. In Japan, "employee inventions" (職務発明 - shokumu hatsumei)—inventions made by an employee that fall within the employer's business scope and relate to the employee's duties—are subject to specific provisions under the Patent Act. A critical aspect of this framework is the "reasonable remuneration" (相当の対価 - sōtō no taika) that an employee is entitled to when the rights to such an invention are transferred to their employer. The Supreme Court of Japan's decision in the Olympus Optical Co. case on April 22, 2003, was a landmark judgment that significantly influenced the interpretation and application of these provisions under the then-existing Patent Act (specifically, the 1959 version, hereafter "Old Act").

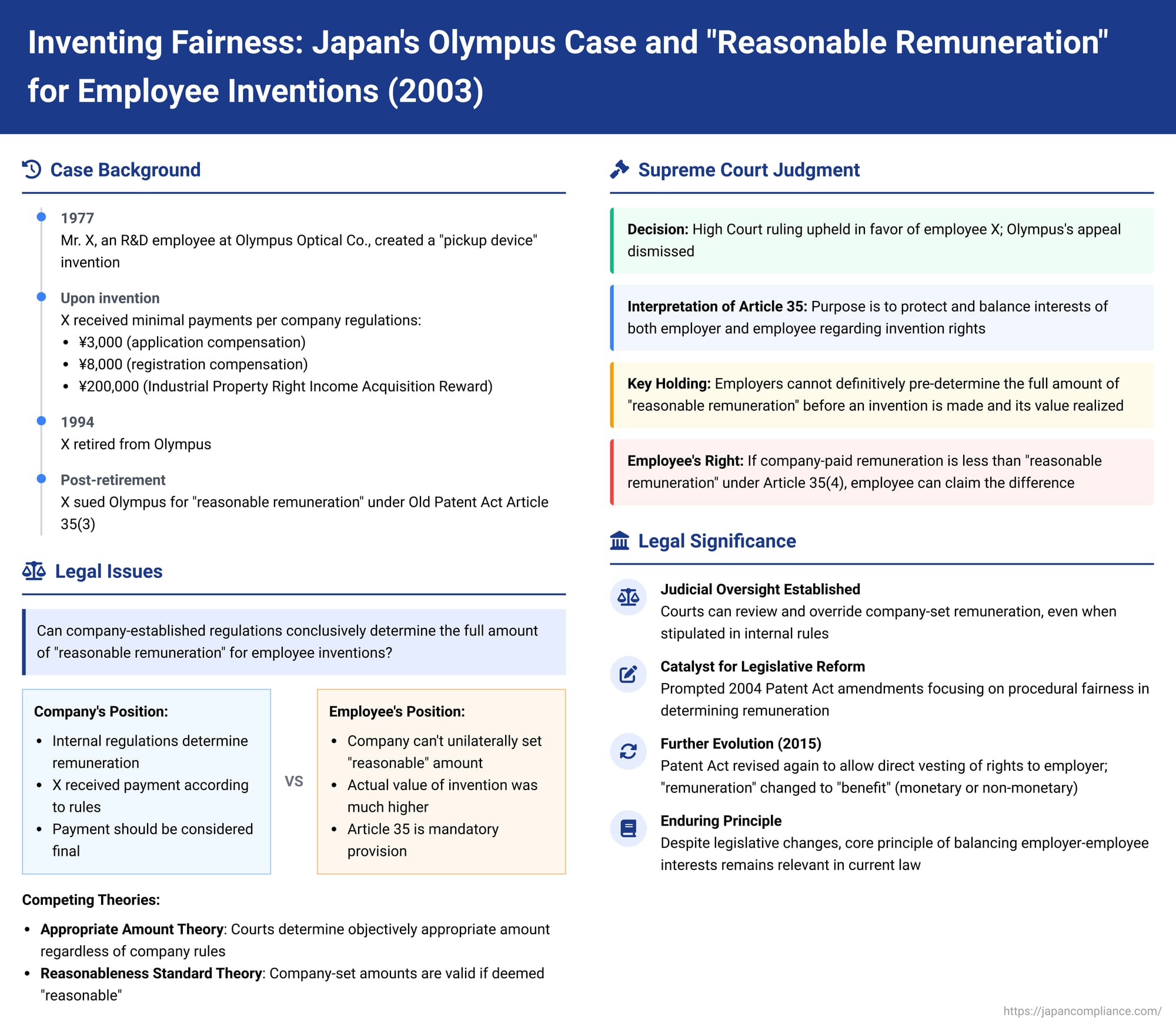

The Olympus Dispute: A "Pickup Device" and a Claim for Fair Reward

The plaintiff, Mr. X, was an employee in the research and development department of Y (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd.), a manufacturer of optical machinery. In 1977, X created an employee invention titled a "pickup device" (referred to as "the P device").

Y had established "Invention Handling Regulations" which stipulated that the rights to employee inventions would be assigned to the company. These regulations also outlined that Y would provide remuneration to the inventing employee, including an "Industrial Property Right Income Acquisition Reward." This specific reward was a one-time payment, capped at 1 million yen, to be made if Y continuously received income from a third party for the employee's invention, covering the first two years of such income.

In accordance with these regulations, Y acquired the patent rights for X's P device. X, in turn, received several payments from Y: 3,000 yen as application compensation, 8,000 yen as registration compensation, and 200,000 yen as the Industrial Property Right Income Acquisition Reward. Mr. X retired from Y in 1994. Subsequently, X filed a lawsuit against Y, claiming "reasonable remuneration" under Article 35, Paragraph 3 of the Old Patent Act for the assignment of his invention.

The Tokyo District Court partially ruled in favor of X, holding that Y's unilaterally established regulations could not definitively bind X regarding the amount of remuneration if that amount fell short of what was legally considered "reasonable remuneration." The Tokyo High Court upheld this, affirming that Articles 35(3) and 35(4) of the Old Patent Act were mandatory provisions. The High Court found Y's payments to be insufficient and awarded X approximately 2.22 million yen as appropriate remuneration. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's 2003 Stance on "Reasonable Remuneration"

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision in favor of X. The Supreme Court's reasoning provided a critical interpretation of the Old Patent Act's provisions on employee inventions:

- Interpreting (Old) Patent Act Article 35: The Court clarified that Article 35 of the Old Patent Act was premised on the principle that the right to obtain a patent for an employee invention originally belongs to the employee who made the invention. The article's purpose was to protect the respective interests of both the employer and the employee concerning the ownership and use of such invention rights and to adjust any conflicting interests between them.

- Limits on Pre-Determining Remuneration: A key finding of the Court was that while employers could, through work rules or other internal regulations, provide for the assignment of invention rights and stipulate terms for remuneration (including amount and timing), it was not permissible to definitively pre-determine the full and final amount of "reasonable remuneration" before an invention was actually made and its specific content and value had materialized. The Court reasoned that the value of an invention is inherently uncertain before its creation.

- Company-Set Remuneration as Potentially Partial Payment: Consequently, any remuneration amount stipulated in company regulations could, at best, be considered a part of the "reasonable remuneration" owed to the employee, but it could not automatically be deemed to constitute the entirety of it. The stipulated amount would only be considered the full "reasonable remuneration" if it truly aligned with the spirit and substance of Article 35, Paragraph 4 of the Old Patent Act, which required consideration of the profit the employer would receive from the invention and the extent of the employer's own contribution to the invention.

- Employee's Right to Claim Shortfall: Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that if the remuneration paid by the employer under its internal regulations was less than the "reasonable remuneration" as determined by considering the factors in Article 35(4) of the Old Patent Act, the employee was entitled to claim the difference from the employer under Article 35(3). This implicitly supported a judicial role in ultimately determining the adequacy of the remuneration.

The "Appropriate Amount" vs. "Reasonableness Standard" Debate

Prior to the Olympus ruling, there were broadly two main schools of thought on how to interpret "reasonable remuneration" under the Old Patent Act:

- Appropriate Amount Theory (適正額基準説 - tekiseigaku kijun-setsu): This theory posited that courts should determine the objectively "appropriate amount" of remuneration, irrespective of what company regulations might state. It viewed Article 35 as having a labor law character, acting as a mandatory provision to protect employees from potentially unfair, unilaterally set remuneration levels, given the unequal bargaining power between employer and employee. Many lower court rulings before Olympus tended to follow this approach.

- Reasonableness Standard Theory (合理性基準説 - gōrisei kijun-setsu): This theory suggested that if the amount of remuneration set by company rules was "reasonable" when viewed against the criteria in Article 35(3) and (4), then that amount should be considered the "reasonable remuneration." It acknowledged the difficulty in precisely valuing an invention and viewed "reasonable remuneration" as a range rather than a fixed point, thereby aligning more closely with existing corporate practices in Japan at the time.

The Supreme Court's decision in Olympus, while not explicitly rejecting the Reasonableness Standard Theory, was seen as leaning closer to the Appropriate Amount Theory. By allowing courts to intervene and award a shortfall if the company-paid amount was insufficient, it affirmed a judicial power to ultimately determine the appropriate level of remuneration. One commentator described the ruling as potentially "diverging from the reality of compensation in many Japanese companies but an unavoidable interpretation of Patent Law Article 35" as it then stood.

Ripple Effects and Legislative Reforms (2004 & 2015 Patent Act Amendments)

The Olympus judgment, along with several other high-profile cases around the same time where substantial sums were awarded to employee-inventors (such as the Hitachi, Nichia Chemical, and Ajinomoto cases, involving awards or claims in the hundreds of millions or even tens of billions of yen ), created significant concern within Japanese industry. This led to calls for legislative reform of Patent Act Article 35.

- The 2004 Amendment: In response to industry pressure, the Patent Act was amended in 2004. This reform largely adopted an approach reflecting the Reasonableness Standard Theory, placing greater emphasis on procedural fairness in the employer's process of determining remuneration. Key changes included:

- A new provision (then Article 35(4), now Article 35(5)) stating that the payment of remuneration should not be found unreasonable if, in determining the standard for such payment, the employer had engaged in consultations with employees (or their representatives), disclosed the standards, and taken into account feedback received.

- Another provision (then Article 35(5), now Article 35(7)) stipulated that if no remuneration rules existed, or if payment under existing rules was deemed unreasonable despite the procedures, then the remuneration amount should be determined by considering factors such as the profit the employer should receive from the invention, the employer's burdens and contributions related to the invention, and the treatment of the employee inventor.

This amendment aimed to give more weight to autonomously agreed-upon company systems for inventor remuneration, provided those systems were developed through fair processes.

- The 2015 Amendment: The Patent Act underwent further significant changes in 2015 concerning employee inventions:

- A new provision (now Article 35(3)) explicitly allowed employment contracts or work rules to stipulate that the right to obtain a patent for an employee invention shall vest directly in the employer from the moment of its creation. This was intended to prevent issues related to double assignment of rights.

- If such direct vesting in the employer occurs, the employee then acquires the right to receive "reasonable monetary or other economic benefit" (「相当の利益」 - sōtō no rieki). The term was changed from "reasonable remuneration" (対価 - taika) to "reasonable benefit" (利益 - rieki) to clarify that this could include non-monetary rewards such as promotions, stock options, or study opportunities, not just cash payments.

- To further promote procedural fairness, a new provision (now Article 35(6)) mandated that the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) establish and publish guidelines concerning the procedures for determining this "reasonable benefit," such as consultation processes between employers and employees.

The Enduring Significance of the Olympus Ruling

Despite these significant legislative amendments, the 2003 Olympus Supreme Court decision retains importance for several reasons:

- Fundamental Interpretation of Purpose: The Olympus case established that Japan's legal framework for employee inventions, as embodied in Patent Act Article 35, is not merely a technical intellectual property regulation but a system designed to balance the respective interests of employers and employee-inventors. This purposive interpretation remains a vital backdrop to understanding the current law.

- Judicial Oversight in Specific Scenarios: Although the amended Patent Act now places greater emphasis on procedural reasonableness in setting remuneration/benefits, the spirit of the Olympus ruling concerning substantive fairness may still come into play. For instance, if an employer meticulously follows all prescribed procedures (consultation, disclosure, etc.) but the resulting "reasonable benefit" offered to the employee is grossly and unjustifiably disproportionate to the invention's value to the employer, or if no internal rules or agreements on remuneration exist at all, courts might still be called upon to assess the substantive fairness of the outcome. In such situations, the judiciary would likely look to the core principles of balancing interests and considering factors like employer profit and employee contribution, as highlighted in the Olympus decision, to determine what constitutes a "reasonable benefit".

Therefore, while the direct application of the Olympus judgment concerning the pre-determination of remuneration under the Old Act has been superseded by legislative changes, its foundational articulation of the purpose behind Japan's employee invention system—the adjustment of interests between employer and employee—continues to hold relevance and inform the interpretation of the current, procedurally focused framework.

Conclusion

The Olympus Optical Co. Supreme Court decision of 2003 was a critical moment in the legal treatment of employee inventions in Japan. It clarified that, under the Old Patent Act, company-stipulated remuneration for inventors was not final and was subject to judicial review to ensure it met the standard of "reasonable remuneration," considering the actual value and benefit derived from the invention. While this ruling acted as a catalyst for significant legislative reforms in 2004 and 2015—reforms that shifted the focus towards procedural fairness in determining inventor rewards—the Olympus case's core insight about the Patent Act's role in balancing employer and employee interests remains an important underlying principle in this evolving area of law.