International Tax Risks in Japan: PE, Transfer Pricing, CFC & Pillar Two Guide for US Companies

TL;DR

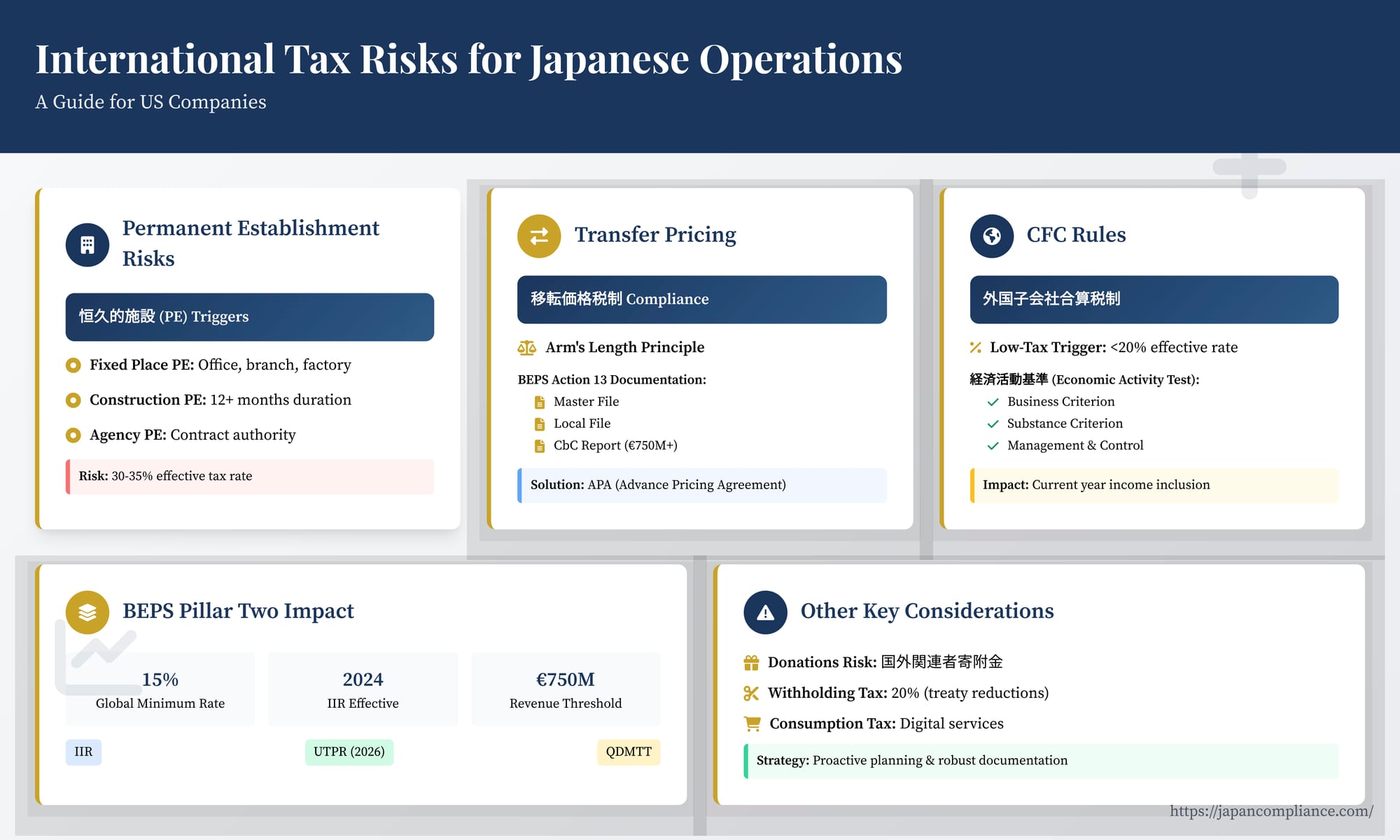

- Japan poses four headline risks for US multinationals: Permanent Establishment, Transfer Pricing, CFC rules and BEPS Pillar Two top-up taxes.

- Mis-steps can push effective tax rates above 35 % or trigger double taxation.

- Careful structuring, robust TP documentation and early modelling of Pillar Two exposures are essential.

Table of Contents

- Permanent Establishment (PE) Risk

- Transfer Pricing

- Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) Rules

- Impact of BEPS Pillar Two (Global Minimum Tax)

- Other Key International Tax Risks

- Risk Management and Conclusion

Expanding business operations into Japan offers significant opportunities, but it also necessitates careful navigation of a complex international tax landscape. US companies establishing a presence in Japan, whether through a branch or a subsidiary, must be cognizant of various Japanese tax rules and potential risks that differ from US domestic tax law. Understanding key areas such as Permanent Establishment (PE) risk, Transfer Pricing (TP), Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) rules, and the implications of global tax reforms like BEPS Pillar Two is crucial for effective tax planning, compliance, and risk mitigation.

This guide provides an overview of these critical international tax considerations for US businesses with operations in Japan.

1. Permanent Establishment (PE) Risk

A fundamental threshold question is whether a US company's activities in Japan create a "Permanent Establishment" (恒久的施設 - kōkyū-teki shisetsu). The existence of a PE generally subjects the foreign company (the US parent or other entity) to Japanese corporate income tax on the profits attributable to that PE.

Defining PE

Japan's domestic law and its network of tax treaties (largely based on the OECD Model Tax Convention) define what constitutes a PE. Common types include:

- Fixed Place of Business PE: Having a fixed place such as an office, branch, factory, or workshop through which the business is wholly or partly carried on. Activities that are purely preparatory or auxiliary in nature (e.g., storage, display, information gathering) generally do not create a fixed place PE, but this exception is interpreted narrowly.

- Construction PE: A building site or construction/installation project constitutes a PE if it lasts for a certain duration (typically 12 months, though treaties vary).

- Agency PE: Arises if a person (other than an independent agent acting in the ordinary course of their business) habitually acts in Japan on behalf of the foreign enterprise and has, and habitually exercises, authority to conclude contracts in the name of the enterprise. The BEPS project has led to refinements internationally aimed at preventing artificial avoidance of agency PE status (e.g., through commissionaire arrangements or splitting contracts), and these trends influence treaty interpretation and domestic practices.

Common Risk Scenarios

- Representative Offices: While often intended solely for preparatory/auxiliary functions (like market research or liaison), exceeding these limited activities can inadvertently create a fixed place PE. Careful management of the office's functions and personnel activities is essential.

- Subsidiary Activities: While a subsidiary is a separate legal entity, the activities of its employees could, in certain circumstances, create an agency PE for the US parent if those employees habitually conclude contracts in the name of the parent or play the principal role leading to contract conclusion without material modification by the parent. This requires careful delineation of roles and responsibilities between parent and subsidiary personnel.

- Service PE (Treaty Dependent): Some treaties (though less common in Japan's older treaties) include provisions where providing services (like consultancy) within Japan for a certain duration can create a PE, even without a fixed base or dependent agent.

Consequences and Mitigation

If a PE is deemed to exist, the attributable profits are subject to Japanese corporate income tax (standard national rate around 23.2%, plus local taxes leading to effective rates often around 30-35% depending on location and size, although a special defense surtax may apply from FY2026 increasing these slightly). Determining attributable profit often involves complex allocation studies. Mitigation involves carefully structuring activities in Japan to remain within non-PE thresholds (e.g., ensuring representative office activities are strictly preparatory/auxiliary) and clearly defining contractual and operational relationships between related entities.

2. Transfer Pricing (移転価格税制 - iten kakaku zeisei)

When a Japanese entity (branch or subsidiary) transacts with a related foreign party (e.g., its US parent or affiliates), Japan's transfer pricing regulations require that the pricing of these transactions adheres to the arm's length principle. This means prices should be consistent with those that would be agreed upon between unrelated parties in comparable circumstances.

Scope and Methods

The rules apply broadly to any cross-border transaction between related parties, including sales of goods, provision of services, licensing of intangibles (royalties), and financial transactions (loans, guarantees). Accepted methods for determining the arm's length price, generally aligned with OECD guidelines, include:

- Comparable Uncontrolled Price (CUP) Method

- Resale Price Method (RPM)

- Cost Plus Method (CPM)

- Profit Split Method (PSM - comparable, contribution, residual)

- Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM)

- Methods equivalent to the above (including potentially the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method for certain intangibles since 2019 reforms).

The "best method rule" applies, requiring selection of the most appropriate method based on the facts and circumstances and availability of reliable comparable data. TNMM is frequently used in practice due to the availability of comparable company data from commercial databases, although its application requires careful functional analysis.

Documentation and Risk Management

Japan has implemented BEPS Action 13 documentation requirements. Companies exceeding certain revenue thresholds involved in cross-border related-party transactions must prepare and maintain (and potentially file):

- Master File: Providing a high-level overview of the multinational group's global business and TP policies.

- Local File: Detailing the specific related-party transactions involving the Japanese entity and the TP analysis supporting their arm's length nature. Simultaneous documentation (preparation by the tax filing deadline) is required for companies meeting certain transaction volume thresholds.

- Country-by-Country (CbC) Report: For MNE groups exceeding global revenue thresholds (€750 million), providing high-level data on revenue, profit, tax paid, and economic activity by jurisdiction.

Failure to maintain adequate documentation can lead to penalties and potentially unfavorable outcomes in audits, including presumptive assessments by tax authorities. Transfer pricing adjustments can be substantial, leading to double taxation if the counterparty jurisdiction does not provide a corresponding adjustment. While the Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP) under tax treaties exists to resolve double taxation, it can be lengthy and uncertain. Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs) – unilateral (with Japanese authorities only) or bilateral (involving Japanese and US authorities) – offer a way to obtain upfront certainty on TP methodologies for future transactions, significantly reducing risk, although they require significant time and resources to negotiate.

3. Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) Rules (外国子会社合算税制 - gaikoku kogaisha gassan zeisei)

Japan's CFC rules, often referred to as "tax haven countermeasures," aim to prevent Japanese corporations (and certain individuals) from artificially deferring Japanese tax on income earned through subsidiaries located in low-tax jurisdictions.

Mechanism and Triggers

If a Japanese company holds a requisite level of shares (directly or indirectly, considering related parties) in a foreign subsidiary that is deemed a CFC, certain income of that CFC may be included in the Japanese parent's taxable income in the current year, even if not distributed as dividends. Key elements include:

- Definition of Foreign Related Company: Based on shareholding ratios (typically >50% control by Japanese residents/corporations, considering direct/indirect ownership and specific rules for "specially related non-residents" which can include relatives residing abroad, as interpreted strictly by courts like the Tokyo District Court on March 16, 2023).

- Low-Tax Trigger: The regime is primarily triggered if the CFC's effective tax rate in its country of residence is below a certain threshold (currently 20% for the main test, although a higher 27% or 30% threshold applies to certain "paper companies," "cash box companies," or those in blacklisted jurisdictions).

- Economic Activity Test (経済活動基準 - keizai katsudō kijun): Even if the tax rate is below 20%, full income inclusion can be avoided if the CFC satisfies all parts of an economic activity test, demonstrating genuine business operations in its location. This test involves multiple criteria:

- Business Criterion (事業基準 - jgyō kijun): The CFC's main business must not be primarily passive investment activities (holding shares/IP, leasing ships/aircraft).

- Substance Criterion (実体基準 - jittai kijun): The CFC must have a fixed place of business (office, factory, etc.) in its country of residence.

- Management and Control Criterion (管理支配基準 - kanri shihai kijun): The CFC must locally manage, control, and conduct its business activities.

- Income Inclusion:

- If the CFC fails the economic activity test (or is a "paper company" etc. taxed below 27%/30%), its entire income is generally subject to inclusion.

- If the CFC passes the economic activity test but is taxed below 20%, only certain types of passive income (e.g., dividends, interest, certain royalties, capital gains) are subject to inclusion.

These rules are highly complex, requiring careful analysis of ownership structures, foreign tax rates, and the substance of foreign operations.

4. Impact of BEPS Pillar Two (Global Minimum Tax)

Adding another layer of complexity is Japan's implementation of the OECD/G20 BEPS Pillar Two framework.

- Income Inclusion Rule (IIR): Japan enacted legislation implementing the IIR, effective for fiscal years beginning on or after April 1, 2024. This applies to multinational enterprise (MNE) groups with consolidated global revenue exceeding €750 million. If a Japanese parent company has subsidiaries in jurisdictions where the group's effective tax rate (ETR) is below the 15% minimum, the Japanese parent may be subject to a "top-up tax" in Japan to bring the tax on that low-taxed income up to the 15% minimum.

- UTPR and QDMTT: Japan also enacted the Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR) and rules for a Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-up Tax (QDMTT) in its 2025 tax reforms, generally expected to apply for fiscal years beginning on or after April 1, 2026.

- Interaction with CFC Rules: Pillar Two and Japan's CFC rules can overlap. Both target low-taxed foreign income. While coordination rules exist and are developing, MNE groups subject to both regimes face increased complexity in calculating potential liabilities under each system and understanding how they interact (e.g., potential credits or ordering). The Japanese government and business groups have acknowledged the need to potentially simplify the CFC rules in light of Pillar Two, but significant reforms are still under consideration.

5. Other Key International Tax Risks

Beyond PE, TP, CFC, and Pillar Two, US companies should also consider:

- Characterization of Intercompany Payments (Donations Risk - 国外関連者寄附金 - kokugai kanrensha kifukin): Japanese tax authorities may scrutinize payments from a Japanese entity to a foreign affiliate (e.g., for management services, royalties, cost-sharing). If the payment is deemed excessive relative to the benefit received, lacks clear contractual basis or economic substance, or if receivables are not diligently collected without justification, the authorities might recharacterize all or part of the payment/uncollected amount as a non-deductible donation to the foreign affiliate, effectively denying a tax deduction in Japan. Robust documentation and clear justification for intercompany charges and credit terms are essential.

- Withholding Taxes: Payments from Japan to foreign entities for dividends, interest, and royalties are generally subject to Japanese withholding tax (typically 20% under domestic law). Tax treaties between Japan and the US often reduce or eliminate these taxes, but claiming treaty benefits requires specific procedures (e.g., filing appropriate forms with the Japanese tax office before payment).

- Consumption Tax: Japan imposes a consumption tax (similar to VAT). US companies providing digital services (e.g., streaming, software downloads, online advertising) to customers (both B2C and B2B) in Japan may have obligations to register, charge, and remit Japanese Consumption Tax, even without a physical presence in Japan.

Risk Management and Conclusion

Operating successfully in Japan requires navigating a multifaceted international tax environment shaped by domestic laws, tax treaties, and rapidly evolving global standards like BEPS. Key risk management strategies for US companies include:

- Proactive Planning: Structure operations and transactions carefully from the outset to manage PE exposure and optimize tax outcomes under applicable treaties.

- Robust Documentation: Maintain comprehensive transfer pricing documentation (Local File, Master File) and detailed intercompany agreements justifying the nature and pricing of all related-party transactions.

- Substance Over Form: Ensure foreign subsidiaries (especially in lower-tax jurisdictions) have genuine economic substance and local management to meet CFC economic activity tests and withstand scrutiny.

- Monitor Global Developments: Stay abreast of ongoing BEPS Pillar Two implementation details and potential future reforms to Japan's CFC rules.

- Seek Expert Advice: Engage qualified Japanese tax advisors early and often to understand specific obligations, navigate complex rules like TP and CFC, ensure treaty benefits are properly claimed, and manage interactions with the National Tax Agency (NTA).

While complex, Japan's international tax rules are generally based on internationally recognized principles. With careful planning, robust documentation, and expert local guidance, US companies can effectively manage their tax risks and focus on building successful business operations in the Japanese market.

- Understanding Japan's Approach to the Global Minimum Tax (Pillar 2): Key Considerations for Multinationals

- Unlocking Japan's Corporate Tax Incentives: A Guide for US Subsidiaries

- EU Data Act Compliance for US Firms with Japanese Links: Key Risks & Strategic Steps

- National Tax Agency – BEPS Pillar Two Guidance (Japanese)

- METI Transfer Pricing APA Guidelines (English PDF)