Internal Controls on Trial: Japan's Supreme Court on Director Duty and 'Unforeseeable' Fraud

Case: Action for Damages

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of July 9, 2009

Case Number: (Ju) No. 1602 of 2008

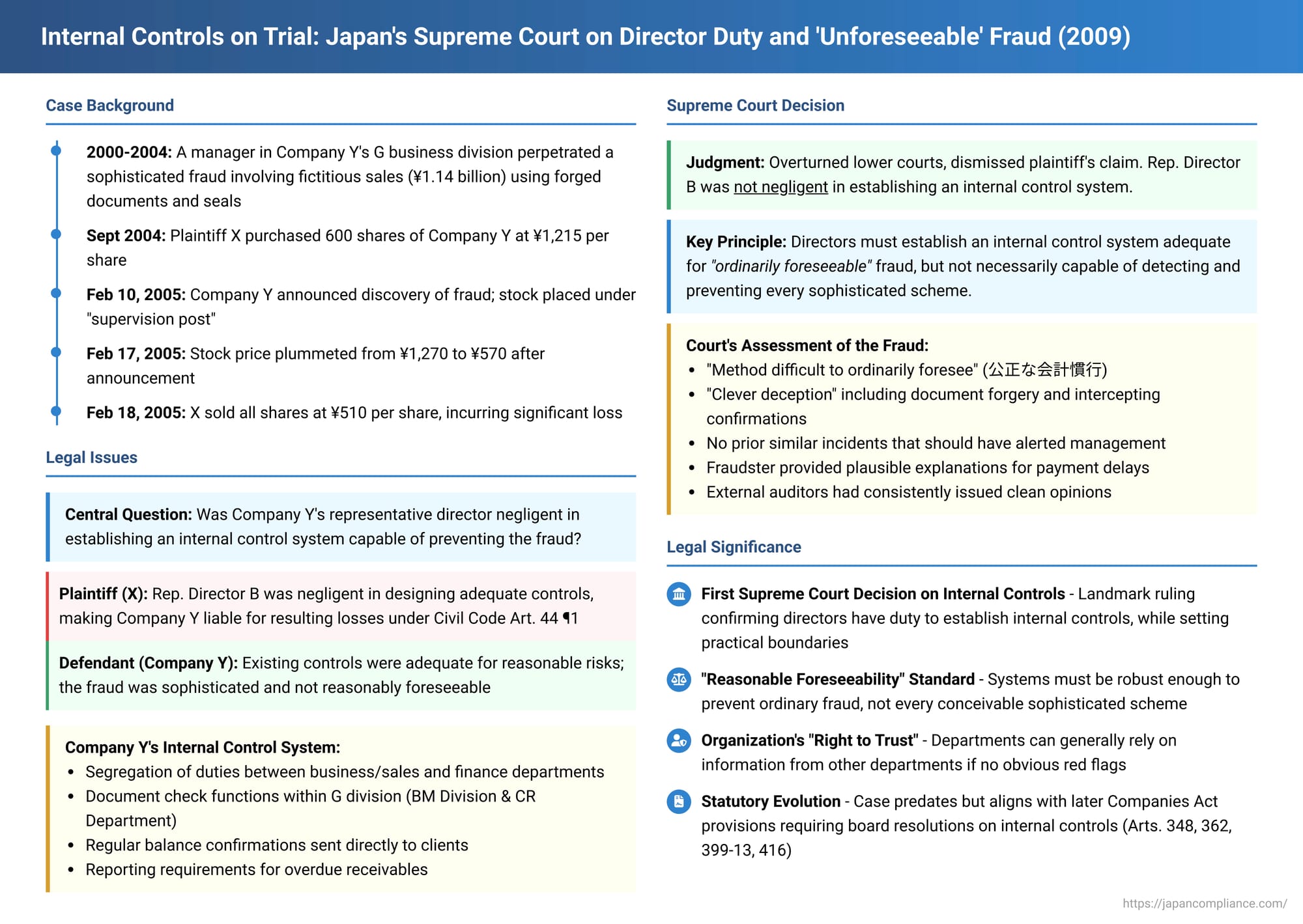

In an era of increasing corporate complexity and regulatory scrutiny, the establishment and maintenance of effective internal control systems have become paramount. Directors, particularly representative directors, bear a significant responsibility in this regard. But what happens when, despite existing controls, a sophisticated internal fraud occurs, leading to financial misstatements and a subsequent collapse in the company's stock price? Can the company itself be held liable to shareholders for the representative director's alleged negligence in failing to build a sufficiently robust internal control system? The Japanese Supreme Court addressed this critical issue for the first time in a landmark judgment on July 9, 2009.

A Sophisticated Fraud Unravels: Facts of the Case

The defendant, Company Y, was a software development and sales company listed on the Second Section of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. The plaintiff, X, was a shareholder who had acquired shares in Company Y in September 2004.

The case stemmed from a prolonged and elaborate fraudulent accounting scheme perpetrated by A, the former manager of Company Y's G business division. Motivated by a desire to maintain his position by showing consistently high performance, A engaged in fictitious sales reporting from approximately September 2000 to December 2004. This scheme involved:

- Fabricating Sales: For transactions that A believed had a high probability of eventually materializing into legitimate orders, he would prematurely recognize revenue. This was done by forging the seals of client sales companies, as well as creating fake order forms and inspection certificates. Over the four-year period, this amounted to approximately 1.14 billion yen in fictitious sales.

- Concealing the Fraud: Naturally, these fictitious sales led to a buildup of non-existent accounts receivable that were perpetually overdue. To cover this up, A and his colleagues employed several deceptive tactics. They would cite plausible-sounding reasons for the payment delays, such as budgetary issues or procedural postponements at the end-user organizations (often universities). More actively, they would misappropriate payments received for legitimate sales and apply them to these fictitious overdue receivables, effectively making it appear as though the fake debts were being settled.

Company Y did have internal control mechanisms in place:

- Segregation of Duties: Business development (sales) and financial departments were organizationally separate.

- Departmental Checks: Within the G business division, there was a "BM Division" (Business Management) responsible for formally checking order forms and inspection certificates, and a separate "CR Department" (Customer Relations) tasked with confirming the operational status of software at client sites. The intended workflow required these checks before sales were reported to the central Finance Department for booking.

- Receivable Confirmations: Company Y's Finance Department, as well as its external auditors, periodically sent balance confirmation letters directly to the sales companies to verify outstanding accounts receivable. For receivables that became overdue, the Finance Department had a procedure requiring the relevant sales departments (like A's G division) to submit reports explaining the reasons for the delay.

Despite these measures, A's sophisticated and concealed fraud went undetected for approximately four years. This resulted in Company Y publishing financial statements (in its securities reports) that contained material misstatements.

The fraud came to light in early 2005. On February 10, 2005, Company Y, upon discovering the不正行為 (fusei kōi - wrongful act), publicly announced that fraudulent accounting practices had been carried out by A and his team. The Tokyo Stock Exchange immediately placed Company Y's stock on a "supervision post," indicating a risk of delisting. The news was widely reported in the following day's newspapers.

The market reaction was severe. Company Y's stock price, which stood at 1,270 yen on February 10, plummeted. After several days of hitting the "stop-low" limit (the maximum permissible daily price decline), the stock closed at 570 yen on February 17, 2005.

The plaintiff, X, had purchased 600 shares of Company Y at an average price of 1,215 yen per share on September 13 and 14, 2004. On February 18, 2005, in the wake of the stock price collapse, X sold all these shares at 510 yen per share, incurring a significant loss.

X then filed a lawsuit against Company Y itself. The claim was based on tort liability (under the then-applicable Civil Code Article 44, Paragraph 1, as applied to companies via the Commercial Code – a liability now covered by Article 350 of the Companies Act). X argued that Company Y's representative director, B, had been negligent in his duty to establish and maintain an adequate internal control system capable of preventing such employee fraud. This alleged negligence, X claimed, led to the fraudulent accounting, the misstated financial reports, the subsequent stock price fall, and X's financial loss.

The Legal Question: Was the Internal Control System Negligently Deficient?

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court, judgment dated November 26, 2007) found in favor of X, at least in part. It held that representative director B had indeed been negligent in fulfilling his duty to establish an adequate internal control system.

The appellate court (Tokyo High Court, judgment dated June 19, 2008) also affirmed that B had breached this duty, and upheld a portion of X's damages claim. Company Y then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: System Was Adequate for "Ordinarily Foreseeable" Fraud

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and dismissed the plaintiff X's claim entirely.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Assessing the Control System and Foreseeability

The Supreme Court meticulously reviewed the facts and found that representative director B had not been negligent. Its reasoning centered on the adequacy of the existing controls relative to the nature of the fraud:

- Company Y's Existing Internal Control System Was Reasonable: The Court acknowledged the internal controls Company Y had in place:

- Organizational separation between business/sales departments and the Finance Department.

- Specific checking functions within the G business division (the BM Division for formal document review and the CR Department for operational software checks) before sales revenue was reported to the Finance Department.

- Regular balance confirmation procedures for accounts receivable conducted independently by both the external audit firm and Company Y's Finance Department, involving direct mailings to the client sales companies.

The Supreme Court concluded from these facts that Company Y had established a management system sufficient to prevent ordinarily foreseeable types of fraudulent activities, such as fictitious sales reporting.

- The Nature of A's Fraud – Sophisticated and Deceptive: The Court characterized the specific fraudulent acts committed by A and his subordinates as being executed "by a method difficult to ordinarily foresee." This involved not just simple misreporting but a "clever deception" (kōmyō na gisō kōsaku), including the forgery of client seals, the fabrication of multiple supporting documents, and active measures to intercept and falsify balance confirmation requests.

- Lack of Specific Foreseeability for Representative Director B: The Court found no special circumstances that should have led representative director B to specifically foresee the occurrence of this particular type of sophisticated fraud. For instance, there was no evidence of similar fraudulent methods having been employed within Company Y previously, which might have put management on higher alert.

- Functioning of the Finance Department's Risk Management: The Court also considered the conduct of the Finance Department. It noted that:

- The reasons provided by A for the overdue receivables (e.g., delays in university budget processes) were plausible on their face.

- Company Y had no history of disputes with the involved sales companies.

- The company's external auditors had consistently issued unqualified ("clean") opinions on Company Y's financial statements during the period of the fraud.

Given these factors, and particularly in light of A's team's "clever deception" in faking the balance confirmations to make them appear legitimate, the Supreme Court held that the Finance Department's failure to directly contact the sales companies to verify the existence of the overdue receivables or the reasons for their delay did not mean that its risk management system was non-functional or that it was negligent. They were, in essence, victims of a well-concealed internal fraud.

- Overall Conclusion on Representative Director B's Negligence: Based on the above points – that Company Y had a reasonable system for ordinary risks, that A's fraud was extraordinarily deceptive and not specifically foreseeable by B, and that the Finance Department's actions were understandable given the sophisticated concealment – the Supreme Court concluded that representative director B could not be found negligent for having breached a duty to establish a risk management system capable of preventing A's specific fraudulent acts.

Analysis and Implications: The Dawn of Supreme Court Jurisprudence on Internal Controls

This 2009 judgment was a landmark, being the first time the Japanese Supreme Court directly ruled on a director's duty related to the establishment of internal control systems.

- Director's Duty to Establish Internal Controls:

While the Supreme Court ultimately found no breach of duty in this case, its entire analysis proceeded on the implicit premise that directors, particularly representative directors, do have a duty to establish appropriate internal control systems. This duty had been previously recognized and developed in several influential lower court decisions (notably the Daiwa Bank shareholder derivative suit, Osaka District Court, September 20, 2000). This Supreme Court decision, by engaging with the merits of whether the duty was breached, effectively acknowledged its existence as a component of a director's broader responsibilities.

It's important to note that this case was a claim by a shareholder directly against the company (under what is now Companies Act Article 350) for damages resulting from the alleged negligence of its representative director in performing his duties. This is distinct from a shareholder derivative suit brought on behalf of the company against directors for breaching their duties to the company (under what is now Companies Act Article 423). Some legal commentary has questioned the directness of linking an RD's failure in establishing internal controls to a company's tort liability towards a shareholder for stock market losses, especially since the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (Article 21-2) now provides a more direct statutory basis for issuer liability for false statements in securities reports (this case predated some of those specific issuer liability reforms or they were not the primary basis of claim here). - Statutory Codification of Internal Control Obligations:

Subsequent to the events in this case, the Companies Act of 2005 (and later amendments) explicitly codified the requirement for boards of directors of certain large companies and companies with specific governance structures (like those with a nomination committee or audit and supervisory committee) to pass resolutions concerning the establishment of internal control systems (e.g., Companies Act Articles 348(4), 362(5), 399-13(1)(i)(b)&(c), 416(1)(i)(b)&(e)). These statutory provisions typically require systems for ensuring compliance with laws and regulations, risk management, the proper execution of director duties, and systems to ensure the effectiveness of audits. The details of these systems and their operational status must also be disclosed in business reports. This statutory framework has formalized and expanded upon the duties that were evolving through case law at the time of this Supreme Court decision. - Internal Controls and Director Liability – Key Distinctions:

When assessing director liability related to internal controls, it's useful to distinguish between:- The Duty to Establish an Adequate System ("System Establishment Duty" - 体制整備義務 - taisei seibi gimu): This concerns whether the directors, particularly top management, have designed and implemented an internal control framework appropriate to the company's size, business, and risks. This Supreme Court case primarily focused on this aspect.

- The Duty to Operate Within and Ensure the Functioning of the System ("System Operation Duty" - 運用義務 - un'yō gimu): This relates to whether individual directors (and employees) are properly fulfilling their roles and responsibilities within the established system.

Even if a robust system exists on paper, if it's not operated effectively or is overridden, liability can still arise. Conversely, even if a specific board resolution on internal controls is flawed or missing (where statutorily required), if an adequate system is nonetheless in place and functioning, it might be difficult to prove damages directly resulted from the flawed resolution itself.

- The Standard for an "Adequate" Internal Control System:

A crucial takeaway from this judgment is that the law does not expect internal control systems to be foolproof or to prevent every conceivable type of fraud, especially highly sophisticated and intentionally concealed misconduct by determined insiders. The Supreme Court indicated that the system needs to be robust enough to prevent "ordinarily foreseeable" types of不正行為 (fusei kōi). It should not be judged with the benefit of hindsight; the assessment must be based on what was reasonable and foreseeable at the time the system was operating.

The application of the business judgment rule to the design of internal control systems is a complex issue. While some argue that determining the appropriate level of control involves resource allocation and risk appetite decisions falling under business judgment, others contend that establishing a baseline, reasonable system is a fundamental duty, and only choices beyond that minimum involve broader discretion. This Supreme Court decision seems to lean towards a standard of "reasonableness for ordinary risks," implying that directors are not expected to design systems to thwart every "difficult to ordinarily foresee" scheme, unless there were specific prior warnings or red flags. - The "Right to Trust" within an Organization:

The Supreme Court's assessment of the Finance Department's conduct is also noteworthy. By noting that the Finance Department was deceived by A's "clever deception," relied on A's plausible explanations for payment delays, had not encountered prior issues with these specific sales companies, and was operating in an environment where external auditors had given clean opinions, the Court implicitly acknowledged a "right to trust." This principle suggests that within a structured organization with segregated duties and established procedures, individuals can generally rely on the information and actions of others performing their designated roles, provided there are no obvious reasons to be suspicious. The Finance Department was not necessarily negligent for being duped by a sophisticated internal fraud if their part of the control system appeared to be functioning based on inputs they had reason to believe were legitimate at the time.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 9, 2009, decision was a seminal moment in Japanese corporate governance law, providing the first high-level judicial guidance on the extent of a representative director's duty to establish internal control systems. While affirming the existence of this duty, the Court set a pragmatic standard: directors are expected to create systems adequate to prevent "ordinarily foreseeable" employee misconduct. They are not, however, absolute guarantors against all forms of fraud. If a particularly sophisticated and well-concealed fraudulent scheme is perpetrated by insiders, and there were no prior specific red flags that should have alerted top management to this unusual risk, a representative director (and, by extension, the company in a tort claim based on the RD's actions) may not be found negligent simply because the existing system failed to prevent that specific, "difficult to ordinarily foresee," fraud. This judgment underscores that while robust internal controls are crucial, there are practical limits to the foreseeability and preventability of all internal wrongdoing, and director liability will be assessed based on the reasonableness of the systems in place relative to normally anticipated risks.