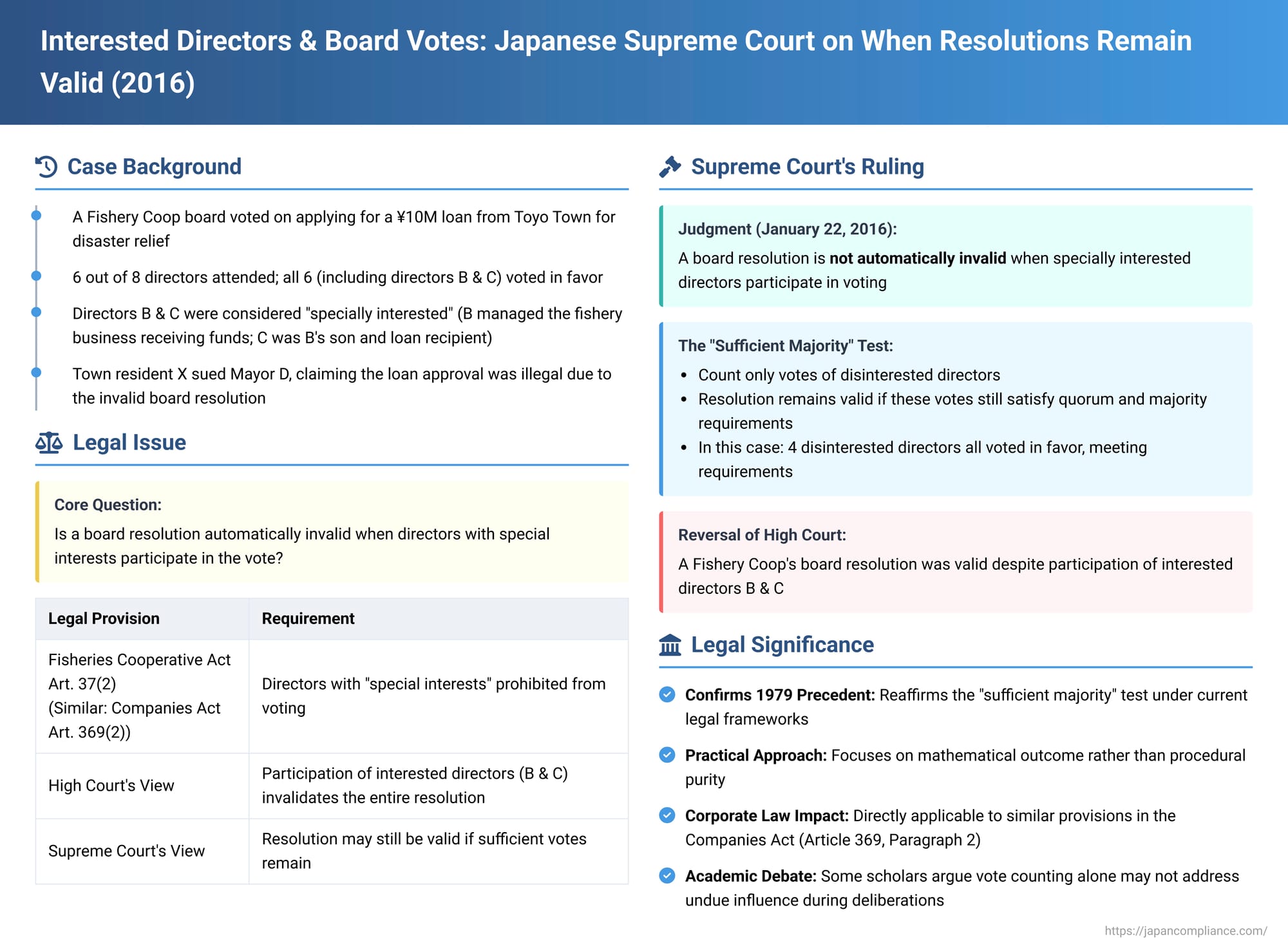

Interested Directors & Board Votes: 2016 Japanese Supreme Court on When Resolutions Remain Valid

Date of Judgment: January 22, 2016

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

Conflicts of interest are a persistent challenge in corporate and cooperative governance. Directors have a duty to act in the best interests of their organization, but what happens when a director has a personal stake in a matter being decided by the board? If such a "specially interested director" participates in a board vote on that matter, is the resulting resolution automatically invalid?

This critical question was addressed by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan in a decision on January 22, 2016. While the case directly concerned a fisheries cooperative, its reasoning has significant implications for the interpretation of similar conflict-of-interest rules applicable to company directors under Japan's Companies Act.

The Legal Principle: Barring Specially Interested Directors from Voting

Japanese law, both for cooperatives (like the Fisheries Cooperative Act, Article 37, Paragraph 2, in this case) and for stock companies (Companies Act, Article 369, Paragraph 2), generally prohibits a director who has a "special interest" in a particular board resolution from participating in the vote on that resolution.

The purpose of this prohibition is twofold:

- To ensure the fairness and impartiality of board deliberations and decisions.

- To protect the interests of the organization (the cooperative or company) from being compromised by a director's personal agenda.

A breach of this rule—meaning a specially interested director does vote—raises questions about the validity of the resolution itself.

Facts of the A Fishery Coop Case

The case arose from a residents' lawsuit concerning a loan made by Toyo Town to A Fishery Coop.

- The Loan Application: A Fishery Coop, seeking to provide disaster relief funds to its members affected by a typhoon, applied to Toyo Town for a 10 million yen loan under a specific town lending regulation. This regulation, although later found by the courts to have been improperly promulgated (publicized), stipulated that a loan application from a cooperative required a prior resolution of the cooperative's board of directors approving the borrowing.

- The Board Resolution: On November 3, 2011, A Fishery Coop's board of directors held a meeting to vote on applying for this loan.

- Out of a total of 8 directors, 6 attended the meeting.

- The resolution to apply for the loan was passed unanimously by all 6 attending directors.

- Among these 6 directors were Mr. B and his son, Mr. C. Mr. B was the manager of "b Kumiai," the fishery business whose members were the intended ultimate beneficiaries of the disaster relief loan. Mr. C subsequently received the 10 million yen as a loan from A Fishery Coop after the coop received the funds from Toyo Town.

- Both B and C were therefore considered "specially interested directors" in the resolution to apply for the town loan.

- The Mayor's Action and Legal Challenge: The Mayor of Toyo Town, Mr. D, approved the 10 million yen loan to A Fishery Coop, and the funds were disbursed. Mr. X, a resident of Toyo Town, filed a lawsuit arguing that this expenditure was illegal. One of X's key arguments was that A Fishery Coop's board resolution approving the loan application was invalid due to the participation of the specially interested directors (B and C), and therefore, the mayor should not have approved the loan. The High Court had sided with X on this point, finding the mayor liable.

The Supreme Court's Decision of January 22, 2016

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's finding regarding the invalidity of the board resolution and the mayor's consequent liability on that specific ground.

Reaffirmation of the "Sufficient Majority" Test

The Court's core reasoning rested on a principle it had previously established in a 1979 Supreme Court precedent:

- Even if a director with a special interest participates in a board vote, the resolution passed is not automatically rendered invalid.

- The resolution remains valid if, after excluding the vote(s) of the specially interested director(s), the remaining votes from the disinterested directors are still sufficient to meet the legal and internal (articles of incorporation) requirements for passing the resolution (i.e., a proper quorum of eligible voters and a necessary majority among them).

Application to A Fishery Coop's Resolution

The Supreme Court applied this test to the facts:

- Directors B and C were indeed specially interested in the loan application resolution.

- The resolution was passed unanimously by all 6 attending directors (including B and C).

- If B and C are excluded from the count of voting directors, 4 disinterested directors remain.

- All 4 of these disinterested directors voted in favor of the resolution.

- The Fisheries Cooperative Act and A Fishery Coop's articles required a resolution to be passed by a majority of directors present who were eligible to vote, provided a quorum of such eligible directors was present. The Supreme Court found that, even when excluding B and C from being able to vote on this specific matter, the attendance of the 4 disinterested directors who all voted in favor satisfied both the quorum requirements (a majority of the 6 directors eligible to vote on this matter if all 8 directors had been present and these 2 were conflicted) and the majority vote requirement among those eligible and present.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that A Fishery Coop's board resolution approving the loan application was valid, despite the participation of B and C in the vote, because the necessary majority was achieved even without counting their votes.

Consequence for the Mayor's Action

Since the coop's board resolution was deemed valid, the mayor's decision to grant the loan based on this resolution (a key loan requirement) was not, in this particular respect, an abuse of discretion or an illegal act. The Supreme Court remanded the case to the High Court to consider other potential grounds of illegality that X had raised concerning the loan.

Significance and Implications (Especially for Company Law)

This 2016 Supreme Court decision, while directly addressing a fisheries cooperative, has significant persuasive authority for the interpretation of analogous provisions in Japan's Companies Act (specifically Article 369, Paragraph 2 concerning specially interested directors at board meetings).

- Consistency Under Current Legal Frameworks: The decision is important because it confirms that the "sufficient majority" test, established under older legal regimes, continues to be the standard for assessing the validity of board resolutions involving the participation of specially interested directors under current laws.

- Impact of Quorum Rules: The PDF commentary notes an interesting point of legal development. The current Companies Act, unlike the old Commercial Code which was in force during the 1979 precedent, explicitly excludes specially interested directors from being counted towards establishing a quorum for a board meeting. Some legal scholars had argued that this newer, stricter quorum rule might imply that specially interested directors should be entirely barred from even attending the meeting or speaking on the matter in which they have an interest. This Supreme Court decision, by reaffirming the logic of the 1979 precedent (which focused on the voting outcome), suggests that while the quorum must be met by disinterested directors, if a resolution still passes with a sufficient majority of those disinterested directors, the mere participation (including voting) by an interested director might not be fatal to the resolution's validity.

- A "Harmless Error" Approach to Voting: The ruling effectively applies a form of "harmless error" principle to the voting participation of specially interested directors: if their vote did not mathematically alter the outcome that would have been reached by the disinterested directors alone, the resolution can stand.

- Ongoing Academic Debate: It's important to acknowledge, as the PDF commentary does, that this numerically focused test is not without its critics in academic circles. A significant counter-argument posits that merely achieving a numerical majority of disinterested votes might not be sufficient to ensure true fairness if the presence, arguments, and influence of the specially interested director(s) unduly swayed the deliberations and the votes of the otherwise disinterested directors. This view calls for a more substantive inquiry into the deliberative process, beyond a simple vote count. The Supreme Court in this particular decision did not delve into this "undue influence" aspect, maintaining its focus on the voting mathematics.

Conclusion

The 2016 Supreme Court decision reaffirms a pragmatic approach to dealing with board resolutions where a specially interested director has participated in the vote. It establishes that such a resolution in a Japanese cooperative (and by strong implication, in a company) is not automatically void. The critical determinant of validity is whether, after disregarding the interested director's vote, the resolution was still approved by a sufficient majority of disinterested directors who met the necessary quorum.

While this "sufficient majority" test provides a degree of legal certainty and prevents resolutions from being easily overturned on technicalities where the outcome was not affected, it also highlights an ongoing discussion within legal scholarship about the thoroughness of such a test in safeguarding against more subtle forms of undue influence. For best governance practices, companies and cooperatives should continue to rigorously enforce policies requiring specially interested directors to fully abstain from voting and, where appropriate, to recuse themselves from deliberations on matters in which they hold a personal interest.