Intent vs. Harm: How Japan's Supreme Court Redefined Forcible Indecency in a Landmark 2017 Ruling

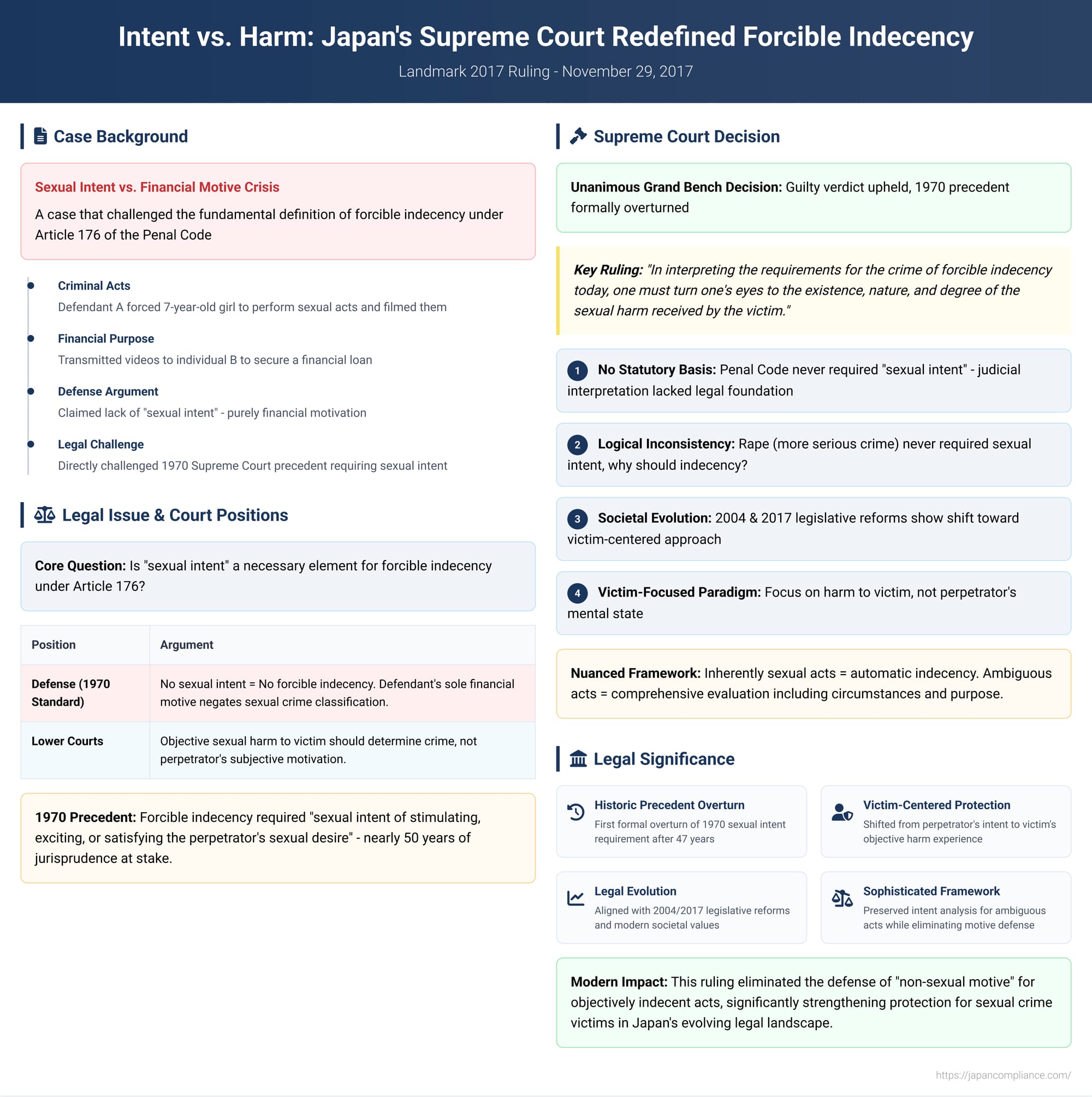

On November 29, 2017, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment that fundamentally reshaped the country's legal landscape concerning sexual offenses. The decision, arising from a case of child sexual abuse, addressed a critical question that had been governed by a nearly 50-year-old precedent: Is a perpetrator's specific "sexual intent" a necessary element to establish the crime of forcible indecency?

In a decisive move, the Court answered in the negative, overturning its 1970 precedent. It declared that the focus of the law should be on the harm inflicted upon the victim, not the internal motivations of the perpetrator. This ruling represents a significant evolution in Japanese jurisprudence, reflecting changing societal values and a deeper understanding of the nature of sexual violence. This article explores the facts of the case, the legal precedent it overturned, and the nuanced reasoning behind the Supreme Court's landmark decision.

The Facts of the Case

The case involved a defendant, identified as A, who was indicted on several charges, including forcible indecency in violation of Article 176 of the Japanese Penal Code. The prosecution's case centered on the following facts:

The defendant, A, forced a seven-year-old girl to perform several sexual acts. These included forcing her to touch his genitals, engaging in oral sex, and touching the victim's own private parts. The defendant then used a smartphone to film these acts. He subsequently transmitted this data to another individual, B, for the purpose of securing a financial loan.

During the trial, the defendant's defense counsel presented a novel argument. They contended that the defendant's actions, while reprehensible, did not constitute the crime of forcible indecency. The core of their argument was that the defendant lacked the requisite "sexual intent." His primary and sole motivation, they claimed, was financial—to obtain a loan from B. He was not, they argued, seeking to stimulate, excite, or satisfy his own sexual desires. Therefore, under the prevailing legal standard at the time, he could not be found guilty of forcible indecency.

The Legal Backdrop: The 1970 Precedent on "Sexual Intent"

To understand the significance of the defendant's argument and the subsequent court decisions, one must look back to a 1970 Supreme Court ruling (the "Shōwa 45 Precedent"). This case had established the legal framework for forcible indecency for nearly half a century.

The 1970 ruling explicitly stated that for the crime of forcible indecency to be established, the act in question must be "performed with the sexual intent of stimulating, exciting, or satisfying the perpetrator's sexual desire."

The court in that case reasoned that if an act, such as forcing a woman to become nude to be photographed, was done exclusively for a purpose other than sexual gratification—for example, for revenge, humiliation, or abuse—it would not constitute forcible indecency. While such an act might constitute another crime, such as coercion (which carried a lighter sentence), it fell outside the scope of a sex crime charge.

This precedent placed the perpetrator's subjective state of mind at the very center of the legal analysis. The objective nature of the act and the experience of the victim were secondary to the question of the perpetrator's internal motivation. It was this precedent that the defendant's counsel in the 2017 case relied upon.

The Lower Courts' Direct Challenge

The trial began at the Kobe District Court. The court was faced with a direct conflict: the acts committed were unambiguously sexual and harmful, yet the defendant's claim of a purely financial motive introduced doubt regarding his "sexual intent" as defined by the 1970 precedent.

The District Court, in its verdict, acknowledged that there was "reasonable doubt" as to whether the defendant acted with a traditional sexual intent, given his professed financial motive. However, in a bold move, the court found him guilty of forcible indecency anyway. It reasoned that the crime is established when an act that objectively infringes upon a victim's sexual freedom is committed, and the perpetrator is aware of this fact. The perpetrator's specific intent, whether for sexual gratification or another purpose, should not be a determining factor in the crime's establishment.

The case was appealed to the Osaka High Court, which upheld the district court's conviction. The High Court went a step further, explicitly stating that the 1970 Supreme Court precedent was no longer tenable in the present day and should not be maintained. By directly challenging the highest court's precedent, the lower courts effectively forced the issue, sending a clear signal that the long-standing interpretation of forcible indecency was out of step with modern legal and social thinking. The case was then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision of 2017

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, composed of all its justices, took up the case to resolve the deep legal conflict. On November 29, 2017, it issued a unanimous decision that not only upheld the defendant's conviction but also formally overturned the 1970 precedent. The Court's reasoning was comprehensive, multi-faceted, and signaled a profound shift in legal philosophy.

1. Lack of Statutory Basis for "Sexual Intent"

The Court began its analysis by examining the text of the law itself. It noted that the Japanese Penal Code, since its enactment, has never contained language requiring "sexual intent" or any other subjective element beyond general criminal intent (koi, or the knowledge and will to commit the act) for the crime of forcible indecency. The requirement of a specific motive related to sexual gratification was a judicial interpretation added by the 1970 Court, not a mandate from the legislature. The 2017 Court found that such a judicially created, extra-statutory requirement lacked a firm basis in the law.

2. Flaws and Inconsistencies in the 1970 Precedent

The Court then critically examined the logic of the old precedent. It found the 1970 ruling to be unpersuasive for several reasons.

First, the old ruling never provided a clear rationale for why the presence or absence of sexual intent should be the critical factor that determines whether an act is the serious felony of forcible indecency or the lesser crime of coercion.

Second, the Court highlighted a significant logical inconsistency. The crime of rape (gōkan-zai, the legal predecessor to the current "forcible sexual intercourse"), which was understood as an aggravated form of forcible indecency, had never been interpreted to require a specific sexual intent. It was illogical, the Court suggested, for the lesser offense (indecency) to require a specific intent that the more serious, aggravated offense (rape) did not. The 1970 precedent had failed to explain or resolve this contradiction.

3. The Imperative of Evolving with Societal Norms

Perhaps the most powerful part of the Court's reasoning was its emphasis on the need for legal interpretation to reflect contemporary societal values. The Court stated that the interpretation of sex-related crimes has a special characteristic: it must take into account the prevailing understanding of society to properly define the scope of punishable conduct.

The Court viewed the 1970 precedent as a product of its time, reflecting the societal consciousness of that era. However, in the decades since, there has been a dramatic shift in public awareness regarding sexual crimes and their impact on victims.

The Court pointed to two major legislative reforms as clear evidence of this societal evolution:

- The 2004 Penal Code Revision: This amendment significantly increased the statutory penalties for sex crimes, including forcible indecency, signaling that society and the legislature viewed these offenses with greater gravity.

- The 2017 Penal Code Revision: This landmark reform, enacted shortly before the Court's decision, further modernized Japan's sex crime laws. It replaced the crime of "rape" with "forcible sexual intercourse," making the law gender-neutral. It also created new offenses to address specific situations of vulnerability, such as abuse by a guardian.

The Court concluded that these legislative changes were a clear reflection of a societal shift toward prioritizing the victim's experience and ensuring that the law could adequately address the realities of sexual harm.

4. A New Paradigm: Focusing on the Victim's Harm

Drawing these threads together, the Supreme Court articulated a new guiding principle for the interpretation of forcible indecency. It declared:

"In interpreting the requirements for the crime of forcible indecency today, one must turn one's eyes to the existence, nature, and degree of the sexual harm received by the victim."

With this statement, the Court formally shifted the legal focus away from the perpetrator's subjective mental state and onto the objective reality of the victim's harm. The argument that a perpetrator's motive was "not sexual" was no longer a viable defense if the act itself was objectively indecent and harmful. The Court concluded that the 1970 precedent, which made the perpetrator's sexual intent a requirement, had "lost its substantive basis for support and can no longer be maintained."

A Nuanced Framework: The Continuing Role of Intent

While the Court abolished "sexual intent" as a mandatory element of the crime, it did not eliminate intent from all consideration. The judgment provided a more nuanced framework for determining what constitutes an "indecent act" (waisetsu na kōi) under Article 176.

The Court recognized that indecent acts fall on a spectrum.

- Inherently Sexual Acts: On one end are acts that are so obviously and inherently sexual in nature that they are considered indecent regardless of the surrounding circumstances or the perpetrator's motive. The acts in the case before the court—forcing a child to perform oral sex and touching her genitals—fell squarely into this category. For such acts, the inquiry into indecency ends there.

- Ambiguous Acts: On the other end are acts that are not inherently sexual and whose character is ambiguous. A touch on the shoulder, for example, could be a gesture of comfort, an accident, or an act of indecency.

For these ambiguous acts, the Court clarified that a determination of indecency requires a comprehensive evaluation of the totality of the circumstances. This includes objective factors such as the specific part of the body touched, the context of the interaction, and the relationship between the parties. Critically, in this context, the court may also consider subjective factors, including the perpetrator's purpose or motive.

For example, an act of touching might be deemed a legitimate medical examination if performed by a doctor for a diagnostic purpose. However, the same physical act could be deemed indecent if the perpetrator's purpose was to humiliate the victim or to gratify a non-sexual but abusive impulse.

Importantly, the Court also suggested that the relevant "purpose" is not limited to traditional sexual gratification. A perpetrator who acts with the express purpose of causing sexual humiliation for revenge may also be found to have committed an "indecent act," as this purpose imbues the act with a sexual meaning.

Conclusion: A New Era in Japanese Sex Crime Law

The Supreme Court's November 29, 2017, decision is a watershed moment in Japanese criminal law. By overturning a long-standing precedent, the Court modernized the legal definition of forcible indecency, aligning it with contemporary societal values and a victim-centered understanding of sexual harm.

The key takeaway is the definitive shift from a perpetrator-focused inquiry into "sexual intent" to a victim-focused analysis of the act and its harmful consequences. The ruling makes clear that one cannot escape liability for an objectively indecent act by claiming a non-sexual motive, such as financial gain or personal revenge.

At the same time, the decision demonstrates judicial sophistication by preserving a role for the analysis of intent in cases involving ambiguous acts. This ensures that the law is applied with careful consideration of the specific facts of each case. This landmark judgment represents not just a change in legal doctrine, but a profound statement about the nature of sexual freedom and the law's paramount duty to protect it.