Intent to Burn, But Not to Endanger? A Japanese Supreme Court Case on the Criminal Mind in Arson

To be found guilty of a crime, a person must generally possess a "guilty mind," or mens rea—they must have intended to commit the wrongful act. But what does this mean for a complex crime like arson? Must an offender only intend to start a fire, or must they also be aware that their fire will create a wider "public danger"? This question probes the very heart of criminal culpability: is a person responsible only for what they specifically intended, or also for the dangerous consequences that naturally flow from their actions?

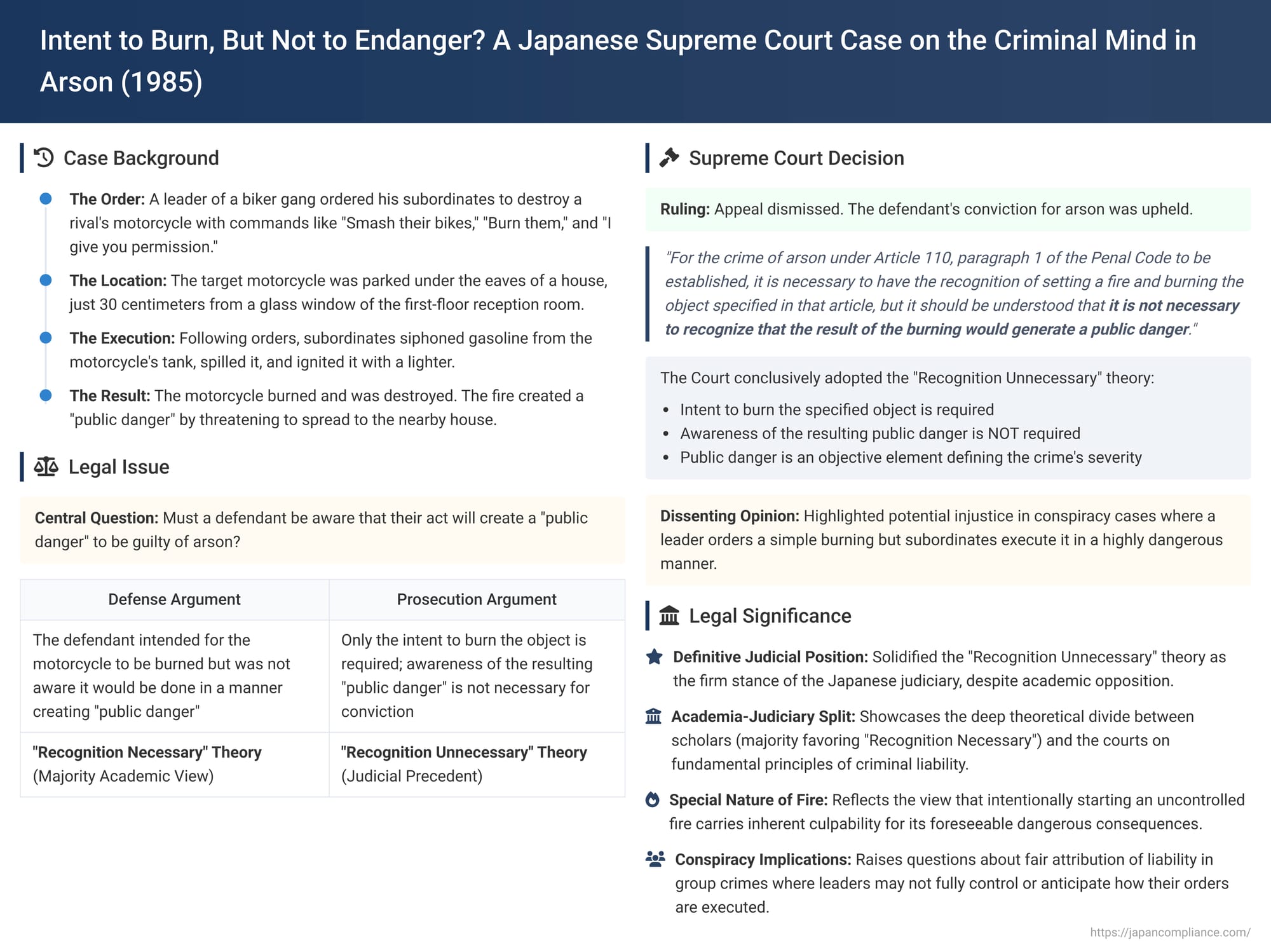

A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 28, 1985, provided a clear, albeit controversial, answer to this question. The case, involving a biker gang leader who ordered the destruction of a rival's motorcycle, solidified the judiciary's long-standing position on the level of intent required for arson, a position that stands in stark contrast to the prevailing view among most legal scholars.

The Facts: The Biker Gang's Revenge

The case originated from a dispute between rival biker gangs (bōsōzoku).

- The Order: The defendant, a leader of one group, conspired with his subordinates to destroy a motorcycle belonging to a member of a rival gang. He gave a series of general commands, such as "Smash their bikes," "Burn them," and "I give you permission."

- The Execution: Following these orders, two of the subordinates, F and E, went to the home of a person named K, where the target motorcycle was parked. The motorcycle was located under the eaves of the house, just 30 centimeters from a glass window of the first-floor reception room. F siphoned gasoline from the motorcycle's tank, let it spill, and ignited it with a lighter.

- The Result: The motorcycle's saddle seat and other parts were set ablaze and destroyed. The fire also created a "public danger" by threatening to spread to K's house.

The defendant was charged as a co-conspirator in the crime of Arson of Objects Other Than Buildings (Article 110 of the Penal Code). His defense argued that he lacked the necessary criminal intent (koi) for this specific crime. While he intended for the motorcycle to be burned (an act of property damage), he claimed he was never aware that it would be done in a manner that created a "public danger."

The Legal Question: Is Awareness of Public Danger Required for Arson?

Certain arson offenses in Japan, including Article 110, are classified as "concrete endangerment crimes." This means that for the crime to be complete, the act must have actually generated a "public danger." The central legal question is whether this element of "public danger" must be part of the defendant's subjective awareness, or if it is an objective consequence for which the defendant is held strictly responsible once they have intended the basic act of burning.

The lower appellate court (the Tokyo High Court) found no evidence that the defendant specifically recognized the risk of public danger. Nevertheless, it convicted him, ruling that Article 110 is a type of "result-aggravated crime" (kekkateki kajūhan) for which awareness of the aggravating result (the public danger) is not required.

The Court's Verdict: The "Recognition Unnecessary" Theory

The Supreme Court upheld the conviction. In a clear and direct statement, it established its official stance on the issue:

"For the crime of arson under Article 110, paragraph 1 of the Penal Code to be established, it is necessary to have the recognition of setting a fire and burning the object specified in that article, but it should be understood that it is not necessary to recognize that the result of the burning would generate a public danger."

This ruling solidified what is known as the "Recognition Unnecessary Theory" (ninshiki fuyō setsu) as the definitive position of the Japanese judiciary. The Court held that the only intent required is the intent to commit the base act: intentionally setting a fire to burn the target object. The resulting public danger is an objective element that defines the severity of the crime, not a subjective element that the defendant must foresee.

A Fierce Debate: The Judiciary vs. The Academy

The Supreme Court's decision, while consistent with prior case law, stands in direct opposition to the majority view in Japanese legal scholarship.

- The "Recognition Necessary" Theory (Prevailing Scholarly View): Most academics argue that awareness of the public danger is, and should be, a necessary component of the criminal intent for arson. Their arguments are compelling:

- The element of "public danger" is what elevates the crime from simple property damage to a grave offense against public safety. To be held liable for this much more serious crime, a defendant's level of culpability should match it; they must be aware of the very danger that makes their act so serious.

- This is especially true for cases of burning one's own property (covered by other arson statutes). The act of burning one's own things is not inherently illegal. The only criminal element is the creation of public danger. Therefore, a defendant cannot have a "guilty mind" unless they are aware of that specific element.

- Arguments for the Court's "Recognition Unnecessary" Theory: The judiciary's position is based on several grounds:

- Statutory Wording: The phrasing of Article 110 ("...and thereby caused a public danger") is structurally similar to that of other result-aggravated crimes where intent for the result is not required.

- The Inherent Danger of Fire: A more modern argument holds that the act of "burning" is fundamentally different from merely "damaging." Fire is inherently uncontrollable and has a high potential to spread. Therefore, anyone who intentionally starts an uncontrolled fire can be said to possess a sufficient level of culpability for the public danger that foreseeably results.

The Conspiracy Conundrum: A Dissenting View

The decision included a powerful separate opinion from one justice who disagreed with the majority. This opinion highlighted a significant potential for injustice under the "Recognition Unnecessary" theory, particularly in conspiracy cases. The justice posed a hypothetical: What if a leader gives a simple order to "burn a motorcycle," intending only an act of property destruction, and the subordinates, on their own initiative, choose to do so in a highly dangerous location next to a house?

Under the majority's rule, the leader would be guilty of the aggravated arson charge, even though he never contemplated the public danger his subordinates created. The dissenting justice argued this was unjust and that such cases should be resolved using the legal principles of "error in complicity" (kyōhan ni okeru sakugo), which would likely limit the leader's liability to the crime he actually intended (property damage).

Conclusion: A Deep Divide with Limited Practical Difference?

The 1985 Supreme Court decision definitively settled the law on this issue from the judiciary's perspective, but it did not end the academic debate. Despite this sharp theoretical divide, legal commentators note that in reality, the practical difference between the two theories is often small. It is difficult to imagine a real-world scenario where an arsonist creates a genuine public danger without having at least a minimal, speculative awareness (a level of intent known as dolus eventualis) that the fire might spread. The true test of the two theories, and the potential for injustice highlighted by the dissenting opinion, lies in those rare cases of conspiracy where the gap between the leader's intent and the subordinate's execution is starkly exposed.