Integrating Business and Human Rights in Japan: Developing and Implementing a Corporate Human Rights Policy

TL;DR

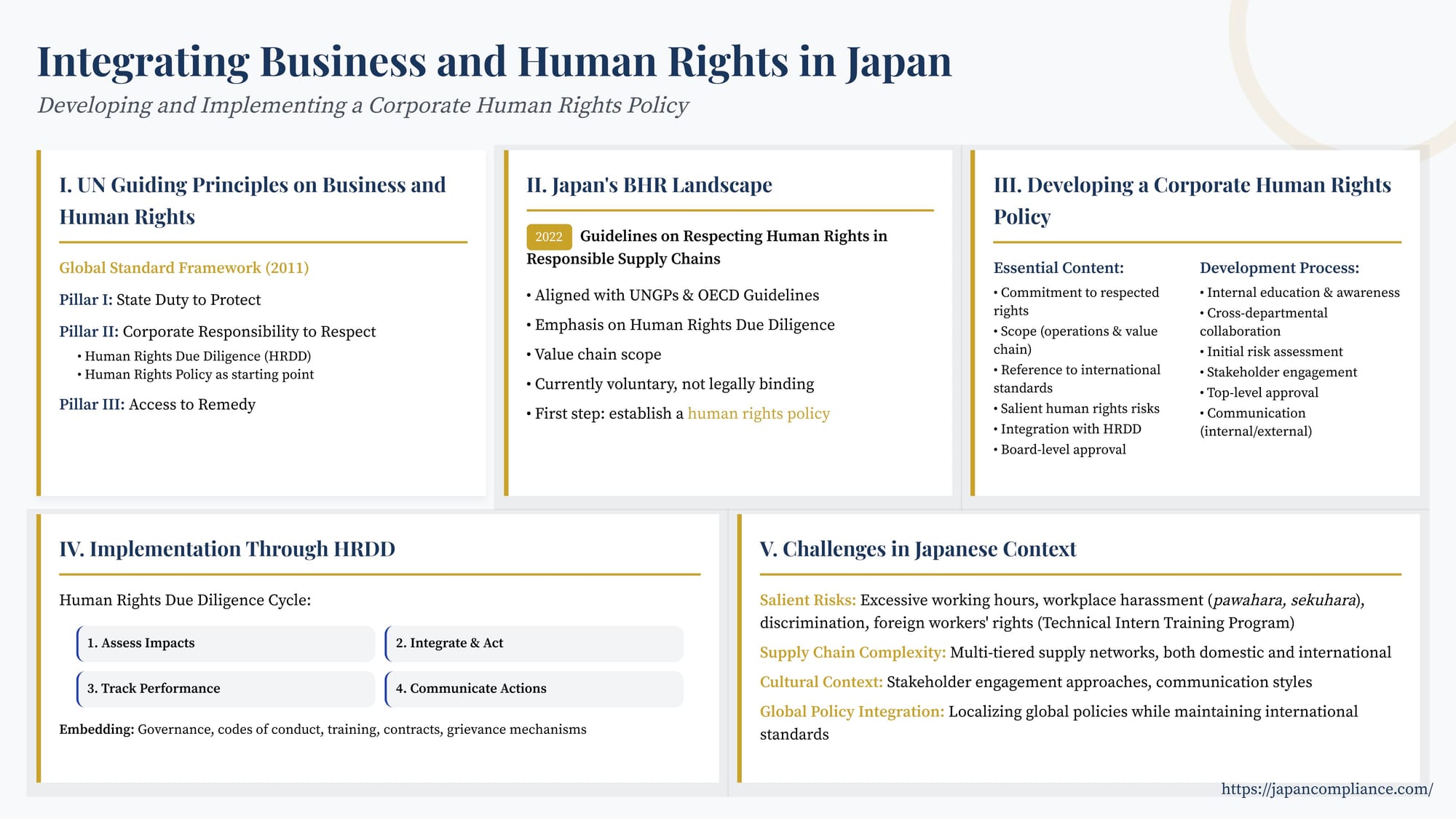

Japan’s 2022 government Guidelines align with the UNGPs and expect companies to publish a board-approved human-rights policy, then run ongoing due diligence. Creating the policy requires cross-functional input, stakeholder dialogue and top-level sign-off; real impact comes from embedding it in supply-chain contracts, training, grievance mechanisms and disclosure.

Table of Contents

- The Global Standard: UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs)

- Japan's BHR Landscape and Government Guidance

- Developing a Corporate Human Rights Policy: Process and Content

- Beyond the Policy Document: Implementation and HRDD

- Grievance Mechanisms and Access to Remedy

- Challenges and Considerations for Multinational Businesses in Japan

- Conclusion

The landscape of corporate responsibility is rapidly evolving globally, with increasing emphasis placed on the impacts businesses have on human rights throughout their value chains. Driven by international standards, regulatory developments, investor pressure, and stakeholder expectations, companies operating across borders are increasingly expected to proactively identify, prevent, and mitigate adverse human rights risks associated with their operations and business relationships. Japan is firmly part of this global trend. The Japanese government has signaled its commitment to promoting responsible business conduct, notably through the issuance of comprehensive guidelines aligning with international frameworks.

For multinational corporations, including US-based businesses with operations, supply chains, or investments in Japan, understanding the Japanese context for Business and Human Rights (BHR) is becoming essential. A foundational element of a credible BHR approach is the development and implementation of a corporate human rights policy. This article explores the key principles and processes involved in creating such a policy within the Japanese context, drawing on international standards and domestic guidance.

The Global Standard: UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs)

The universally recognized framework for BHR is the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011. The UNGPs rest on three pillars:

- The State Duty to Protect: Governments must protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including businesses.

- The Corporate Responsibility to Respect: Businesses have an independent responsibility to respect human rights, meaning they should avoid infringing on the rights of others and address adverse impacts with which they are involved.

- Access to Remedy: Victims of business-related human rights abuses must have access to effective remedy, through both judicial and non-judicial mechanisms.

Central to the corporate responsibility to respect (Pillar II) is the expectation that businesses will undertake Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD). This is an ongoing risk management process to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for how a company addresses its adverse human rights impacts. A public human rights policy serves as the essential starting point, articulating the company's commitment and providing a framework for its HRDD efforts.

Japan's BHR Landscape and Government Guidance

Japan has demonstrated growing engagement with the BHR agenda. While perhaps lagging slightly behind some European jurisdictions in terms of mandatory HRDD legislation (as of early 2025), the government has taken significant steps to promote voluntary action aligned with the UNGPs.

A key development was the publication in September 2022 of the "Guidelines on Respecting Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains, etc." (責任あるサプライチェーン等における人権尊重のためのガイドライン, Sekinin aru Supply Chain tō ni okeru Jinken Sonchō no tame no Guideline). Developed through multi-stakeholder consultations involving government ministries, business associations, labor unions, and civil society organizations, these Guidelines serve as the government's primary guidance document for Japanese companies on implementing their responsibility to respect human rights.

Key features of the Guidelines include:

- Alignment with UNGPs: They explicitly reference and are structured around the UNGPs and other international standards like the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises.

- Emphasis on HRDD: The core recommendation is for companies to establish and implement an HRDD process appropriate to their size, sector, and operational context.

- Scope: The Guidelines encourage companies to consider impacts not only within their own operations but also throughout their supply chains and other business relationships.

- Voluntary Nature: While not legally binding mandatory legislation, the Guidelines represent a strong governmental expectation and are becoming an influential benchmark for responsible business practice in Japan. They signal the direction of travel and may inform future legislative or regulatory developments.

The Guidelines explicitly state that the first step in undertaking HRDD is for a company to establish and disclose a human rights policy.

Developing a Corporate Human Rights Policy: Process and Content

A human rights policy is more than just a statement; it's the strategic foundation for embedding respect for human rights throughout a company's operations. Based on the UNGPs, the Japanese Guidelines, and evolving corporate practice, an effective policy and its development process typically involve the following:

1. Purpose and Foundational Content:

The policy should clearly state the company's commitment to respecting human rights. Essential content elements generally include:

- Commitment: An unambiguous statement of commitment to respect internationally recognized human rights, often referencing core documents like the International Bill of Human Rights (Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) and the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

- Scope: Clarification that the commitment applies to the company's own operations and personnel, and outlining expectations towards business partners, suppliers, and other relevant stakeholders across the value chain.

- UNGPs Alignment: Explicit acknowledgment of the corporate responsibility to respect human rights as articulated in the UNGPs.

- Salient Issues (Optional but Recommended): While the main policy might be high-level, some companies choose to reference their most salient (most severe potential) human rights risks, demonstrating awareness.

- Integration: Mentioning how the policy connects to the company's HRDD processes and overall risk management.

- Remedy: Indicating the company's commitment to providing or cooperating in remediation processes and referencing available grievance mechanisms.

- Governance: Stating that the policy has been approved at the highest level of the company (e.g., Board of Directors).

2. The Development Process:

Creating a meaningful policy requires more than just drafting text; it involves internal engagement and understanding. Insights from the experiences of Japanese companies that have undertaken this process highlight several key steps:

- Planning and Internal Education: The initial phase involves understanding the task and building internal awareness. This often includes educating key personnel and leadership about international BHR norms (UNGPs, OECD Guidelines), the company's potential human rights footprint, and the rationale for developing a policy. Engaging external experts or conducting internal seminars can be crucial, especially as BHR concepts might be relatively new to some departments.

- Cross-Departmental Collaboration: Human rights issues cut across various corporate functions. Effective policy development requires input and buy-in from multiple departments beyond just CSR or Legal. Procurement/Supply Chain Management (supplier risks), Human Resources (labor rights, harassment, diversity), Environmental Health & Safety (community impacts, worker safety), Business Units (operational impacts), and Legal/Compliance (regulatory alignment, risk management) are all key stakeholders. Establishing a cross-functional working group can facilitate this collaboration.

- Initial Risk Assessment / Identifying Salient Issues: Before finalizing the policy content, it's vital to have a preliminary understanding of the company's potential human rights risks. This doesn't necessarily require a full-scale HRDD at this stage, but internal workshops involving representatives from different departments can help identify potential high-risk areas based on the company's sector, geographic footprint, business model, and known industry challenges. For example, a manufacturing company might focus initially on supply chain labor conditions, occupational health and safety, and potential environmental impacts on local communities. Discussions about internal issues like harassment or rights of foreign workers might also emerge. This initial assessment helps ensure the policy commitments are grounded in the company's reality.

- Stakeholder Engagement (Internal & External): While the initial focus might be internal, the UNGPs emphasize the importance of consulting potentially affected stakeholders. This could involve discussions with employee representatives, unions, suppliers, local community groups, or relevant civil society organizations (CSOs/NGOs). While potentially challenging, external input can provide valuable perspectives on risks and expectations, enhancing the policy's credibility and relevance. Even if extensive external consultation isn't feasible during initial policy drafting, acknowledging the importance of ongoing stakeholder dialogue within the policy itself is recommended.

- Drafting and Refinement: The policy should be drafted in clear, accessible language. The cross-departmental group often takes the lead, potentially with expert support. Iterative review and feedback within the company are important.

- Top-Level Approval and Communication: Securing formal approval from the highest governance body (typically the Board of Directors) is essential for demonstrating senior leadership commitment, as stressed by the UNGPs and the Japanese Guidelines. Communicating the policy effectively both internally (to all employees) and externally (e.g., on the company website) is the final step in the development phase. Consistent reporting to leadership on the BHR agenda's progress is also vital for sustained engagement.

Experiences suggest that while this process requires time and resources, the internal dialogue and cross-functional collaboration fostered during policy development are invaluable for building the shared understanding necessary for effective implementation later on. Rushing the process or drafting the policy in isolation risks creating a document disconnected from the company's actual risks and operational realities.

Beyond the Policy Document: Implementation and HRDD

A human rights policy is only effective if it is actively implemented and embedded within the company's culture and operations. The Japanese Guidelines, following the UNGPs, emphasize that the policy should be the starting point for an ongoing Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD) process. This involves:

- Assessing Impacts: Regularly identifying and assessing actual and potential adverse human rights impacts connected to the company's operations, products, services, and business relationships (including supply chains). This requires gathering information from various sources, potentially including desk research, supplier questionnaires (Self-Assessment Questionnaires or SAQs), audits, and direct stakeholder engagement.

- Integrating Findings and Taking Action: Incorporating the findings from impact assessments into relevant internal functions and processes. Developing and implementing action plans to prevent and mitigate identified risks. This might involve revising procurement practices, strengthening supplier codes of conduct, improving workplace safety protocols, providing specific training, or engaging with business partners to address shared risks.

- Tracking Performance: Monitoring the effectiveness of the actions taken to address adverse human rights impacts. This involves setting relevant indicators and regularly reviewing progress.

- Communicating Actions: Reporting externally on how the company identifies and addresses human rights impacts. This is increasingly expected through sustainability reports, dedicated human rights reports, or compliance with non-financial disclosure regulations (such as those related to Japan's "Human Capital Visualization Guidelines" - 人的資本可視化指針, Jinteki Shihon Kashika Shishin, where relevant human rights aspects might intersect).

Embedding the policy also means integrating its principles into:

- Corporate Governance: Assigning board and senior management oversight for human rights performance.

- Codes of Conduct: Reflecting human rights commitments in employee codes and supplier codes of conduct.

- Training: Providing appropriate training to employees and relevant business partners on the human rights policy and expectations.

- Contracts: Incorporating human rights clauses into supplier contracts and other relevant agreements.

Grievance Mechanisms and Access to Remedy

The UNGPs (Pillar III) and the Japanese Guidelines also highlight the importance of access to remedy. Companies are expected to establish or participate in effective grievance mechanisms for individuals and communities who may be adversely impacted to raise concerns and seek remediation. These mechanisms should be legitimate, accessible, predictable, equitable, transparent, rights-compatible, and based on dialogue and engagement. They can include company-level hotlines, dialogue processes, or collaboration with existing industry or multi-stakeholder mechanisms.

Challenges and Considerations for Multinational Businesses in Japan

While the BHR framework is increasingly global, applying it in the Japanese context involves specific considerations:

- Identifying Salient Risks: Companies need to understand the particular human rights risks prevalent in their sector within Japan and its associated supply chains. Issues often highlighted include excessive working hours, workplace harassment (power harassment - パワハラ, pawahara, sexual harassment - セクハラ, sekuhara), discrimination (gender, LGBTQ+, minorities), challenges related to the rights of foreign workers (including those under the controversial Technical Intern Training Program - 外国人技能実習制度, gaikokujin ginō jisshū seido), and downstream environmental impacts.

- Supply Chain Complexity: Mapping and assessing risks deep within complex, multi-tiered supply chains, both domestic and international, remains a significant challenge. Collaboration with suppliers and industry initiatives is often necessary.

- Cultural Context: Stakeholder engagement and communication strategies need to be culturally appropriate. Building trust and navigating communication styles effectively is key.

- Integrating Global Policies: Multinational companies need to ensure their global human rights policies are effectively implemented and understood within their Japanese operations, subsidiaries, and business relationships, potentially requiring translation, localized training, and adaptation to local legal nuances while maintaining core international standards.

Conclusion

The expectation for businesses to respect human rights is no longer a niche concern but a growing mainstream requirement for operating responsibly in the global economy, including in Japan. The Japanese government's 2022 Guidelines provide clear direction, aligning domestic expectations with international standards like the UN Guiding Principles. Developing a robust corporate human rights policy is the crucial first step, signaling commitment and providing a framework for action. However, the real value lies in its effective implementation – embedding respect for human rights into corporate culture, conducting ongoing human rights due diligence across the value chain, engaging meaningfully with stakeholders, and providing access to remedy when adverse impacts occur. For US and other multinational companies, proactively integrating BHR principles into their Japanese operations and supply chains is not only aligned with global best practices but is increasingly essential for maintaining reputation, managing risk, and ensuring long-term business sustainability in this vital market.

- Navigating Japan's New Human Rights Due Diligence Guidelines: A Guide for US Businesses

- Japan's Human Rights Due Diligence: Navigating New Expectations for Your Supply Chain

- ESG in Japan: Reshaping Investment Paradigms and Corporate Governance

- METI: Guidelines on Respecting Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains (Japanese)