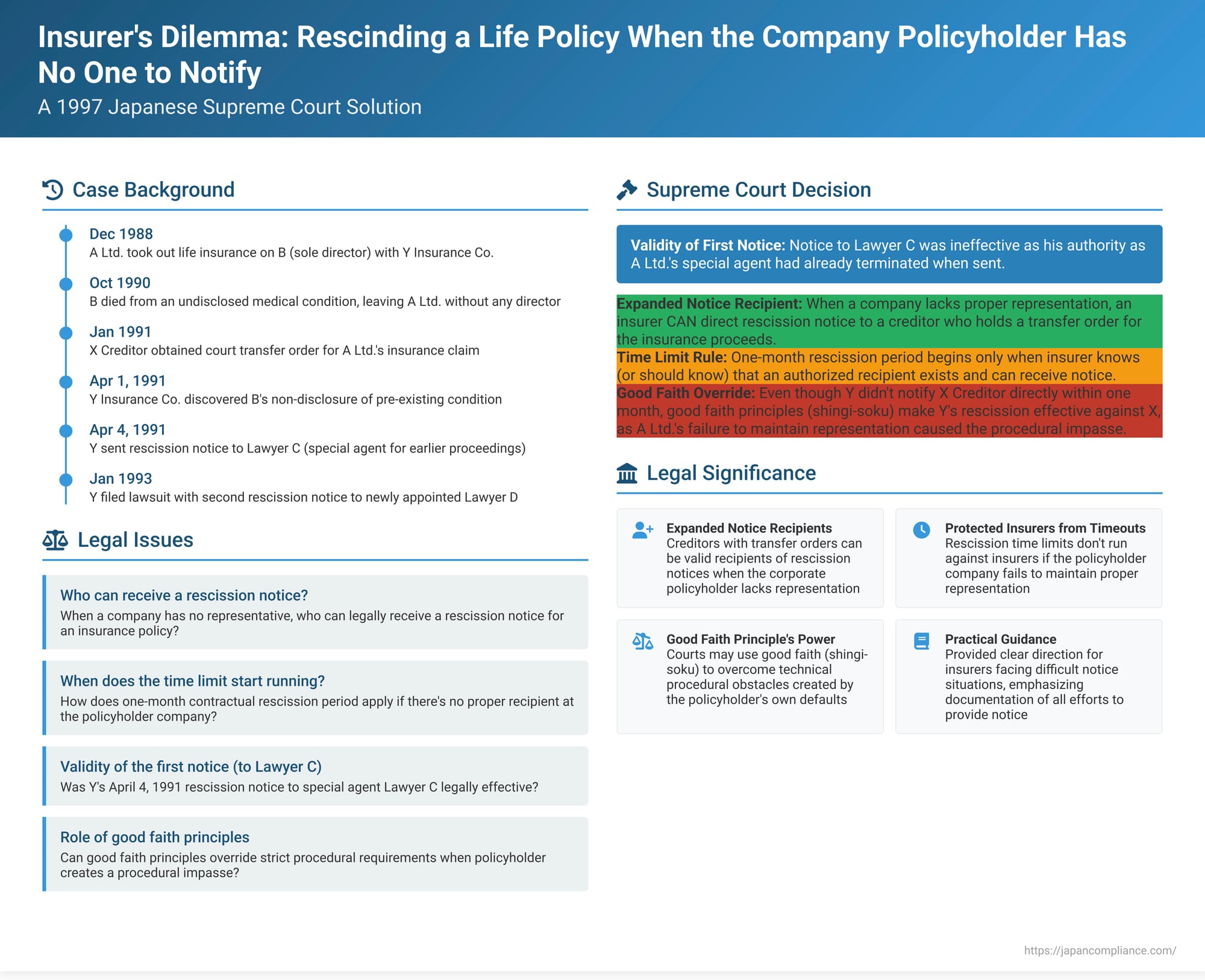

Insurer's Dilemma: Rescinding a Life Policy When the Company Policyholder Has No One to Notify – A 1997 Japanese Supreme Court Solution

Judgment Date: June 17, 1997

Court: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench

Case Name: Claim for Transferred Receivables Case

Case Number: Heisei 7 (O) No. 949 of 1995

Introduction: The Complexities of Policy Rescission and Corporate Representation

An insurer's right to rescind an insurance policy, particularly a life insurance policy, due to a material misrepresentation or non-disclosure by the insured at the time of application, is a fundamental tool for protecting against anti-selection and fraud. However, the exercise of this right is typically subject to strict procedural requirements, including providing timely and proper notice of rescission to the correct party – usually the policyholder.

But what happens when the policyholder is a company, and due to unforeseen circumstances, it finds itself without any legal representative (like a director) authorized to receive such a crucial notice? This situation can become even more intricate if the insured person under the policy (who might also have been the company's sole director) has died, and a creditor of the now unrepresented company has already legally attached and obtained a court "transfer order" (転付命令 - tenpu meirei) for the anticipated life insurance proceeds.

To whom can the insurer validly direct its notice of rescission in such a scenario? How does the contractual time limit for rescission (often a short period, such as one month after the insurer discovers the grounds for rescission) operate if there is no readily identifiable party to receive the notice? And can the overarching legal principle of good faith and fair dealing play a role in determining the effectiveness of a rescission if strict procedural compliance was hampered by the policyholder's own failure to maintain representation? These thorny issues were at the center of a significant 1997 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Facts: A Deceased Director, A Company Without Representation, An Attaching Creditor, and a Late Discovery of Non-Disclosure

The case involved A Ltd., a Japanese limited company (yūgen kaisha). On December 8, 1988, A Ltd. took out a life insurance policy on the life of Mr. B, who was its sole director. A Ltd. was named as both the policyholder and the beneficiary of this policy, which had a sum insured of 25 million yen. The policy was issued by Y Insurance Company. A crucial term in the policy stipulated that if the insurer discovered grounds for rescission (such as a breach of the duty of disclosure), it could not rescind the contract if one month had passed since the day it became aware of those grounds.

It later transpired that Mr. B had a serious pre-existing medical condition – a dissecting aortic aneurysm – for which he had previously received inpatient medical treatment for two months. However, at the time the life insurance contract was concluded, this significant medical history was not disclosed to Y Insurance Company; instead, false statements were allegedly made regarding Mr. B's health.

On October 23, Heisei 2 (1990), Mr. B died as a result of a ruptured dissecting aortic aneurysm, triggering a potential claim under the life insurance policy. Upon Mr. B's death, A Ltd., whose sole director he had been, was left without any serving directors, and a successor was not promptly appointed. This created a situation where A Ltd. had no individual legally authorized to act on its behalf or to receive official notices.

Meanwhile, X Creditor Co., which was owed money by A Ltd., took legal steps to recover its debt. On January 23, Heisei 3 (1991), X Creditor Co. successfully petitioned the court to appoint Lawyer C as a "special agent" (特別代理人 - tokubetsu dairinin) for A Ltd., specifically for the purpose of X Creditor Co.'s proceedings to secure the insurance money. On the same day, X Creditor Co. obtained a court order attaching A Ltd.'s life insurance claim against Y Insurance Company and, importantly, a "transfer order." This transfer order effectively assigned A Ltd.'s right to the 25 million yen insurance proceeds directly to X Creditor Co. in satisfaction of A Ltd.'s debt to X. This court order was formally served on Y Insurance Company on January 28, 1991, and on Lawyer C (as A Ltd.'s special agent for that proceeding) on February 1, 1991. The order became final and legally binding on February 8, 1991.

Some time after these events, on April 1, Heisei 3 (1991), Y Insurance Company discovered the facts concerning Mr. B's original non-disclosure of his serious medical condition – clear grounds for rescinding the life insurance policy. Faced with this discovery and the one-month contractual time limit for rescission, Y Insurance Company attempted to act:

- Rescission Notice 1: On April 4, Heisei 3 (1991), Y Company sent a formal notice of rescission, citing Mr. B's non-disclosure. This notice was addressed to A Ltd. via Lawyer C (the special agent who had been appointed for X Creditor Co.'s earlier attachment proceedings) and was mailed to A Ltd.'s registered address. It was delivered on the same day.

- Rescission Notice 2: Considerably later, on January 8, Heisei 5 (1993) – well beyond the initial one-month window from April 1, 1991 – Y Insurance Company filed a lawsuit against A Ltd., seeking a court declaration that it had no obligation to pay the life insurance proceeds (a declaratory judgment of non-liability). For the purpose of this new lawsuit, the court appointed a different special agent for A Ltd., Lawyer D. The complaint served in this lawsuit, which was delivered to Lawyer D on January 21, Heisei 5, also contained a statement asserting Y Company's rescission of the insurance contract.

X Creditor Co., having obtained the transfer order for the insurance proceeds, subsequently sued Y Insurance Company to compel payment. Y Company defended this lawsuit by asserting that the life insurance policy had been validly rescinded due to Mr. B's material non-disclosures.

The Core Legal Questions Before the Supreme Court

The case presented several intricate legal questions for the Supreme Court:

- Validity of Rescission Notice 1: Was the first rescission notice, sent to Lawyer C, legally effective? This depended on whether Lawyer C's authority as a special agent for A Ltd. (which had been granted for the earlier, separate attachment proceedings initiated by X Creditor Co.) was still valid and sufficient for him to receive such a critical notice on behalf of A Ltd. at the time Y Company sent it.

- Timeliness of Rescission Notice 2 (if Notice 1 was invalid): If the first notice was ineffective, had Y Company's one-month contractual right to rescind the policy already expired by the time the second notice (contained within the lawsuit documents served on the newly appointed special agent, Lawyer D, in Heisei 5) was delivered?

- The Addressee of Rescission When the Policyholder Company is Unrepresented but a Creditor Holds a Transfer Order: In a situation where a corporate policyholder, like A Ltd., has no directors or other legal representatives capable of receiving notices, can an insurer validly direct its notice of policy rescission to an attaching creditor who has already obtained a final and binding transfer order for the insurance policy proceeds?

- Operation of the Contractual Time Limit for Rescission When No Proper Recipient Exists: How does a contractual time limit for exercising a right of rescission (e.g., one month from the insurer discovering the grounds) apply if, during that period, there is genuinely no one at the policyholder company properly authorized to receive such a notice? Does the clock start running regardless, potentially causing the insurer to lose its right through no fault of its own if it cannot find a valid recipient?

- The Role of Good Faith and Fair Dealing: Could the overarching legal principle of good faith and fair dealing (shingi-soku) play a role in determining the effectiveness of a rescission if strict adherence to procedural requirements for notice was made exceptionally difficult or impossible due to the policyholder company's own failure to maintain proper legal representation, especially if the insurer could demonstrate it had made reasonable efforts to exercise its rescission right?

The Lower Courts' Rulings

The lower courts had reached different conclusions:

- Court of First Instance (Osaka District Court): This court had ruled in favor of X Creditor Co. It found that Rescission Notice 1 (sent to Lawyer C) was invalid because Lawyer C's authority as a special agent for A Ltd. had effectively ended once the attachment and transfer order proceedings for which he was appointed had concluded. It also found that Rescission Notice 2 (contained in the lawsuit documents served on Lawyer D much later) was delivered well after the one-month contractual time limit for rescission (calculated from when Y Company learned of the non-disclosure on April 1, 1991) had expired. Thus, the rescission was deemed ineffective, and Y Company was liable.

- Appellate Court (Osaka High Court): On appeal, the Osaka High Court reversed the first instance decision and ruled in favor of Y Insurance Company, dismissing X Creditor Co.'s claim. The High Court found that Rescission Notice 2 was effective to rescind the policy, essentially concluding that the rescission was timely and valid under the circumstances.

X Creditor Co. then appealed the High Court's adverse decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (June 17, 1997): A Solution Based on Good Faith in a Procedural Impasse

The Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, ultimately dismissed X Creditor Co.'s appeal. It upheld the High Court's conclusion that Y Insurance Company's rescission of the policy was effective against X Creditor Co., meaning Y Company was not liable to pay the insurance proceeds. However, the Supreme Court's reasoning for reaching this conclusion was significantly different and more nuanced than that of the High Court, involving novel interpretations of whom an insurer can notify and the application of the principle of good faith.

Invalidity of Rescission Notice 1 (to Lawyer C)

The Supreme Court first agreed with the court of first instance (and implicitly with the High Court on this point, though the High Court had focused on Notice 2) that Rescission Notice 1, which Y Company had sent to Lawyer C, was indeed legally ineffective. The Court reasoned that Lawyer C's appointment as a special agent for A Ltd. had been specifically for the purpose of representing A Ltd. in X Creditor Co.'s earlier attachment and transfer order proceedings. By April 4, Heisei 3 (1991), when Y Company sent its rescission notice to him, those proceedings had concluded, and Lawyer C's authority as a special agent for A Ltd. had therefore terminated. At that specific moment, A Ltd. was again effectively without any director or other person properly authorized to receive such a significant legal notice on its behalf.

To Whom Can a Rescission Notice Be Directed When the Policyholder Company is Unrepresented but the Insurance Claim Has Been Transferred to a Creditor?

This was a central and novel point in the Supreme Court's judgment. The Court laid down an important new principle:

In a situation where (a) the policyholder and beneficiary of a life insurance policy is a limited company, (b) its sole insured director has died, and (c) the company is consequently left without any director or other person who possesses the authority to receive legal notices on its behalf, IF a creditor of that company has, by that time, obtained a valid and final court transfer order for the company's life insurance claim against the insurer, then the insurer can also make its declaration of intent to rescind the life insurance contract (for legitimate reasons such as non-disclosure by the insured) effective against that attaching creditor who now holds the legal right to the insurance proceeds.

The Supreme Court provided several rationales for this significant extension of the potential addressee for a rescission notice:

- Creditor's Strong Interest: After the insured person's death, the primary outstanding legal issue concerning the life insurance contract is typically the payment of the death benefit. The attaching creditor, who has obtained a legally binding transfer order for this very benefit, now holds the most direct and substantial financial interest in the ultimate fate of the contract (i.e., whether it will be paid out or validly rescinded).

- Policyholder Company's Diminished Interest and Culpability: The policyholder company (A Ltd. in this case), having no serving director and having its primary asset under the policy (the right to the insurance proceeds) effectively transferred away to the creditor, has a significantly diminished direct interest in the contract's validity. Moreover, the company's failure to appoint a successor director – a basic and fundamental duty of corporate governance – is a fault attributable to the company itself. In such circumstances, the Supreme Court suggested, the company effectively forfeits its right to be the exclusive recipient of such critical notices if another party (the attaching creditor) now stands to directly gain or lose based on the insurer's decision to rescind. It is acceptable for the company to lose the opportunity to receive the notice directly if it has failed to maintain its own legal capacity to do so.

- Analogy to Beneficiary Notification: The position of the attaching creditor who holds a transfer order for the insurance proceeds is, in some respects, analogous to that of a specifically named beneficiary in other insurance contexts. Standard insurance policies and some statutory provisions (like the former Simplified Life Insurance Act Article 41, Paragraph 1) often allowed an insurer to provide notice to a beneficiary if the policyholder themselves could not be located or notified. The Supreme Court saw the attaching creditor in this scenario as being in a comparable position regarding their interest in the policy.

When Does the Contractual One-Month Time Limit for Rescission Start Running if There is No One at the Policyholder Company to Receive Notice?

The life insurance policy in this case contained a common clause stipulating that the insurer's right to rescind the contract for reasons such as non-disclosure would lapse if it was not exercised within one month of the insurer becoming aware of the grounds for rescission. The Supreme Court then addressed how this one-month time limit should be applied when, at the moment the insurer discovers the grounds for rescission, the policyholder company has no directors or other authorized representatives capable of receiving the rescission notice.

The Court held that in such circumstances – where the absence of a proper recipient for the notice is usually due to a failure or default on the part of the policyholder company itself (e.g., its failure to appoint a successor director after the death of its sole director) – it would be excessively harsh and unfair to the insurer for its legitimate right of rescission to simply expire within the one-month period merely because it cannot physically deliver the notice to an existing, authorized representative of the company. The Court also noted the practical difficulty for an insurer to quickly become aware if and when a successor director might eventually be appointed, especially if the company does not proactively inform the insurer.

Therefore, the Supreme Court ruled that the one-month period for exercising the right of rescission will only begin to run from the time the insurance company knows, or reasonably should have known, that an authorized recipient (such as a newly appointed director or a legally appointed special agent for the company) has appeared and is capable of receiving the notice.

Application of These Principles to the Facts of This Case – And the Decisive Role of Good Faith and Fair Dealing (Shingi-soku)

Applying these newly clarified principles to the specific timeline of Mr. X Creditor Co.'s case, the Supreme Court reached an initial, somewhat technical, conclusion:

- When Y Insurance Company learned of Mr. B's non-disclosure on April 1, Heisei 3 (1991), A Ltd. (the policyholder company) did indeed lack a director or other authorized representative.

- However, by that same date, X Creditor Co. had already obtained its final and effective transfer order for the life insurance proceeds.

- Applying the new principle established by the Supreme Court (that an attaching creditor with a transfer order can be a valid recipient of a rescission notice when the company is unrepresented), Y Insurance Company could have directed its rescission notice to X Creditor Co. on or after April 1, 1991.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court reasoned, the one-month contractual time limit for Y Company to rescind the policy should have started to run from April 1, 1991, with respect to X Creditor Co. (as the party then entitled to receive such notice).

- However, Y Insurance Company did not send a valid rescission notice directly to X Creditor Co. within that one-month period. (As noted, Rescission Notice 1, sent on April 4 to Lawyer C, was deemed ineffective because Lawyer C's specific agency for A Ltd. had already terminated).

This technical finding would, on its own, have suggested that Y Company's right to rescind had lapsed. However, the Supreme Court did not stop there. It then invoked the overarching legal principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義則 - shingi-soku) to ultimately uphold the effectiveness of Y Company's rescission against X Creditor Co. The Court's reasoning for this crucial "good faith override" was as follows:

- Y Insurance Company, although it may not have fully realized at the time that it could or should notify X Creditor Co. directly (as this was a legally novel point being clarified by this very judgment), did make significant and demonstrable efforts to rescind the policy as soon as it learned of the grounds for doing so. It promptly sent its first rescission notice (albeit to a party whose agency had, unbeknownst to it perhaps, terminated). Later, it took the further step of initiating a lawsuit against A Ltd. seeking a judicial declaration of non-liability, and the complaint in that lawsuit (which contained a renewed declaration of rescission) was properly served on a newly court-appointed special agent for A Ltd. (Lawyer D) in Heisei 5 (1993). These actions, the Supreme Court found, showed that Y Company was actively and diligently trying to exercise its rescission right under exceptionally difficult procedural circumstances.

- In stark contrast, A Ltd., the policyholder company, was primarily at fault for creating and perpetuating the procedural impasse. Its complete failure to appoint a successor director for a prolonged period (from Mr. B's death in late 1990 until at least early 1993 when the second special agent was appointed for Y Company's lawsuit) was a fundamental breach of its basic corporate governance responsibilities. This failure effectively obstructed Y Company's ability to deliver a conventional rescission notice to a duly authorized representative of the company.

- The Supreme Court concluded that it would be grossly unfair and contrary to the principle of good faith to allow A Ltd.'s own serious default (and by extension, to allow X Creditor Co., which now stood in A Ltd.'s shoes with respect to the insurance claim) to cause Y Insurance Company to lose its otherwise legitimate right to rescind the policy for a clear and material non-disclosure by the insured.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the overall sequence of events and the diligent efforts made by Y Company to rescind, when viewed in light of A Ltd.'s prolonged failure to have proper legal representation, should be treated under the principle of good faith and fair dealing as being legally equivalent to Y Company's rescission notice having effectively reached X Creditor Co. before Y Company's rescission right had legally expired.

- As a result, Y Company could validly assert the effect of the rescission against X Creditor Co., and X Creditor Co.'s claim for the insurance proceeds therefore failed.

Analysis and Implications of this Important Ruling

The 1997 Supreme Court of Japan decision in this intricate life insurance case provides several important takeaways for insurers, policyholders, and their creditors:

1. Expansion of Potential Addressees for an Insurer's Rescission Notice in Specific Circumstances:

A key legal development from this judgment is the expansion of the category of persons to whom an insurer can validly direct a notice of policy rescission. It establishes that when a corporate policyholder is effectively defunct or lacks any legal representation (e.g., due to the death of its sole director), and a creditor has already obtained a final and binding transfer order for the insurance policy proceeds, that attaching creditor can now be considered a valid recipient of such a critical notice from the insurer. This provides a much-needed practical solution for insurers who might otherwise be stymied in exercising their legal rights due to a procedural void created by the policyholder's own circumstances.

2. Tolling of Contractual Rescission Time Limits in Cases of Policyholder Default:

The ruling also provides significant protection to insurers regarding the strict contractual time limits (often very short, like one month) for exercising a right of rescission. The Supreme Court held that such a time limit will not begin to run against the insurer if, at the time the insurer discovers the grounds for rescission, the policyholder company has no authorized person available to receive the rescission notice. The clock only starts ticking from the time the insurer knows, or reasonably should have known, that a proper recipient (such as a newly appointed director or a court-appointed special agent) has come into existence. This prevents insurers from unfairly losing their substantive rights due to procedural difficulties caused by the policyholder's own failure to maintain proper corporate representation.

3. The Overriding Power of Good Faith and Fair Dealing (Shingi-soku) in Addressing Procedural Impasses:

Perhaps the most striking and widely discussed aspect of this decision is its ultimate reliance on the broad equitable principle of good faith and fair dealing (shingi-soku) to uphold the insurer's rescission, even though the Court found that the insurer had technically failed to notify the correct party (the attaching creditor, X Creditor Co.) strictly within the primary one-month window (once that window was deemed to have started). This demonstrates the Japanese judiciary's willingness, in exceptional circumstances, to look beyond strict procedural compliance to achieve an outcome that it perceives as equitable and just, especially when one party has made demonstrable efforts to act and the other party is largely responsible for creating or prolonging the procedural difficulty.

4. Important Guidance for Insurers Faced with Difficult Notice Situations:

This case offers valuable lessons for insurance companies that encounter situations where a corporate policyholder becomes unrepresented, making formal notice of rescission problematic:

- Insurers should act diligently to ascertain if any third party (such as an attaching creditor who has already obtained a transfer order for the policy proceeds) has acquired a direct and legally recognized interest in the policy proceeds. If so, that party may now be a proper (and perhaps even necessary) recipient for any notices affecting the policy's validity.

- If no such third party is immediately apparent, and the contractual rescission clock is potentially ticking (or might start ticking once a representative is known), taking proactive steps like initiating a lawsuit against the unrepresented company (which would typically lead to the court appointing a special agent to represent the company for the purpose of that lawsuit) can be a recognized and effective method of ensuring that a formal notice of rescission is eventually served on a legally authorized representative.

- Throughout the process, it is crucial for insurers to meticulously document all their efforts to provide notice and to exercise their rescission rights. This documentation can be vital if they later need to make an argument based on good faith, as Y Insurance Company successfully did in this case.

5. Key Considerations for Creditors Attaching Insurance Proceeds:

Creditors who succeed in attaching insurance policy proceeds and obtaining a transfer order must now be aware that they may become the direct recipients of important notices from the insurer, including potentially notices of policy rescission. They also need to understand that their hard-won claim to the insurance proceeds can still be defeated if the insurer subsequently discovers and can prove valid grounds for rescinding the original insurance contract due to the policyholder's or insured's prior misconduct (such as material non-disclosure at the time of application). The creditor, in this sense, steps into the shoes of the policyholder and takes the insurance claim subject to all valid defenses the insurer might have had against the policyholder.

6. The Potentially Limited Scope of the "Good Faith Rescue" for Insurers:

As legal commentary (such as the PDF provided with this case) has pointed out, the Supreme Court's ultimate use of the good faith principle to "save" Y Insurance Company's rescission in this specific instance might have been influenced, in part, by the legal novelty at the time of its ruling that an attaching creditor could be a proper recipient for a rescission notice. Now that the Supreme Court has clearly established this principle, insurers in future similar cases would likely be expected by the courts to notify the attaching creditor directly and promptly within the standard contractual time limits. A failure to do so in future cases might not receive the same degree of "good faith" indulgence from the courts as was extended in this particular 1997 judgment.

Conclusion

The June 17, 1997, Supreme Court of Japan decision is a highly significant ruling that navigates a complex intersection of insurance law, corporate law, and civil procedure, particularly concerning an insurer's right to rescind a life insurance policy when faced with a corporate policyholder that lacks legal representation and when a third-party creditor has already secured rights to the insurance proceeds.

The Court established important principles:

- In such circumstances, the insurer can validly direct its notice of rescission to the attaching creditor who holds a final transfer order for the policy benefits.

- The contractual time limit for the insurer to exercise its right of rescission (e.g., typically one month from the insurer learning the grounds for rescission) will not begin to run if the policyholder company has no authorized person available to receive such a notice, until such time as the insurer knows, or reasonably should know, that a proper recipient has become available.

Most notably, even though the insurer in this specific case was found to have not technically notified the correct party (the attaching creditor) strictly within the primary one-month window (once that window was deemed by the Court to have started running against the creditor), the Supreme Court, in a powerful application of the overarching legal principle of good faith and fair dealing (shingi-soku), found the insurer's rescission to be ultimately effective against the creditor. This was due to the insurer's demonstrable and diligent efforts to rescind under exceptionally difficult procedural circumstances, which were created primarily by the policyholder company's own prolonged failure to appoint a director and thereby maintain proper legal representation.

This judgment highlights the Japanese judiciary's pragmatic approach to resolving procedural impasses in complex insurance disputes. It balances the insurer's substantive right to rescind a policy for valid reasons (such as material non-disclosure by the insured) against the procedural need for proper notice, while ultimately ensuring that a party's significant fault in creating a procedural void does not lead to a grossly unfair or inequitable outcome. It underscores the profound importance of all parties involved in an insurance relationship acting in good faith.