Insurance Lapse Without Warning? Japanese Supreme Court Scrutinizes "No-Notice Lapse" Clauses Under Consumer Contract Act

Judgment Date: March 16, 2012

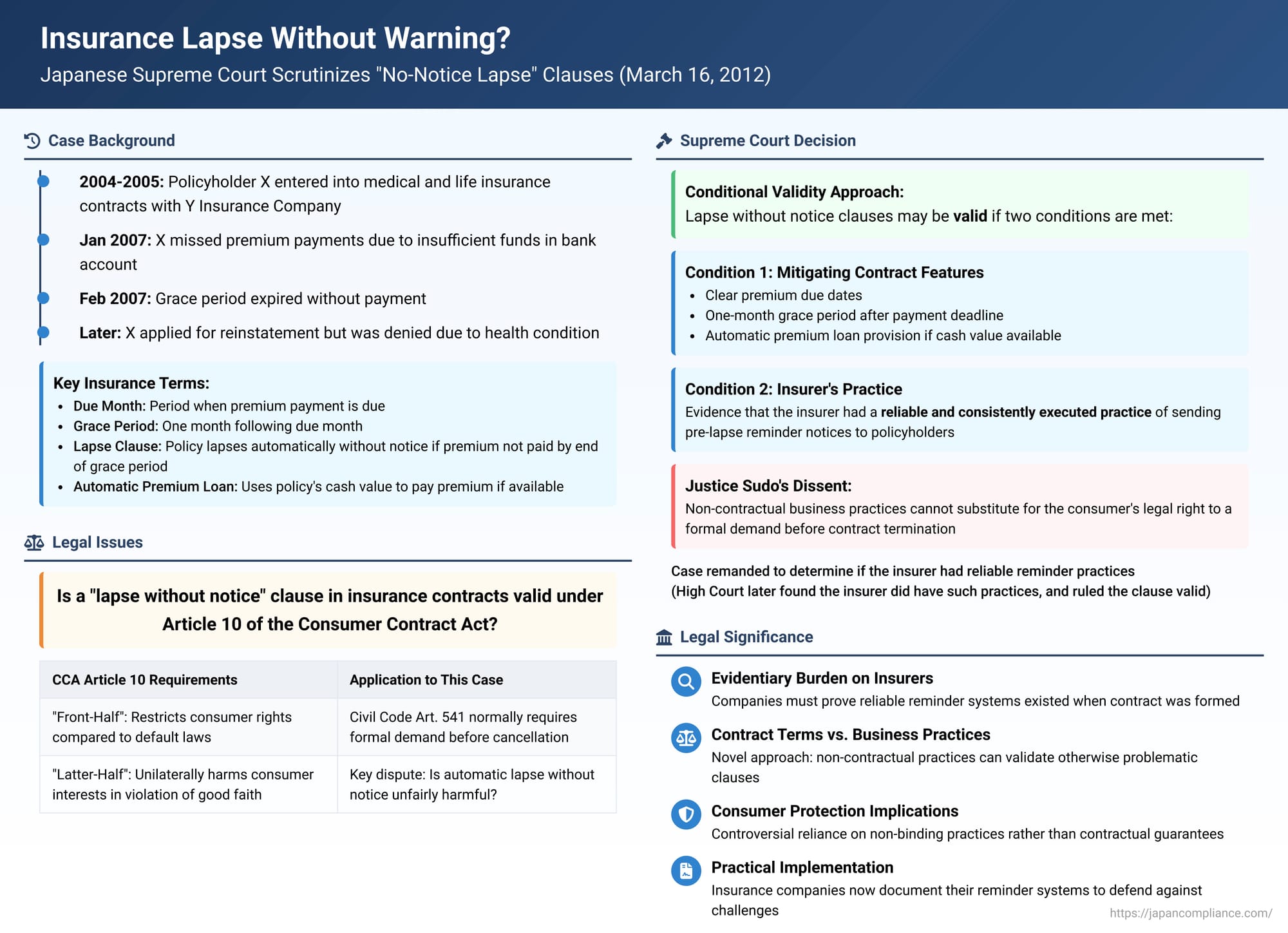

For many individuals, life and medical insurance policies represent a crucial safety net. The regular payment of premiums is essential to keep this coverage active. But what happens if a policyholder inadvertently misses a premium payment? Can their vital insurance coverage simply disappear without a formal warning or demand for payment from the insurer? This question was at the heart of a significant Japanese Supreme Court decision on March 16, 2012 (Heisei 22 (Ju) No. 332), where the Court examined the validity of "lapse without notice" clauses in insurance contracts under Article 10 of Japan's Consumer Contract Act (CCA).

The Policyholder, the Policies, and the Missed Payment

The plaintiff, X, had entered into two insurance contracts with the defendant, Y Life Insurance Company: a medical insurance policy on August 1, 2004, and a life insurance policy on March 1, 2005. Both policies, which involved monthly premium payments, were acknowledged as "consumer contracts" falling under the purview of the Consumer Contract Act.

The policy terms (約款 - yakkan) applicable to both contracts contained several important clauses regarding premium payments and contract validity:

- Premium Due Date: For the second premium onwards, payment was due within the contract's anniversary month (e.g., if the contract started August 1st, the August premium was due between August 1st and August 31st). This period was referred to as the "due month" (払込期月 - haraikomiki-zuki).

- Grace Period: A grace period (猶予期間 - yūyo kikan) for premium payment was provided, lasting from the first day to the last day of the month following the due month. For example, if the January premium was due by January 31st, the grace period would extend through February 28th/29th.

- Lapse Clause (本件失効条項 - honken shikkō jōkō): This was the central clause in dispute. It stipulated that if the premium was not paid within the grace period, the insurance contract would automatically "lose its effect" (i.e., lapse) effective from the day immediately following the end of the grace period. Notably, this lapse occurred without any requirement for the insurer to first issue a formal demand for payment (催告 - saikoku) to the policyholder.

- Automatic Premium Loan Clause (本件自動貸付条項 - honken jidō kashitsuke jōkō): The terms also included a provision stating that if a premium remained unpaid after the grace period, but the total amount of overdue premiums plus interest did not exceed the policy's cash surrender value, Y Insurance Company would automatically lend the policyholder the necessary premium amount to keep the contract in force. This loan would be deemed to have been made on the last day of the grace period, with interest accruing at a prescribed rate.

- Reinstatement Clause (本件復活条項 - honken fukkatsu jōkō): If a policy lapsed, the policyholder could apply for its reinstatement within a certain period (1 year for the medical policy, 3 years for the life policy), subject to Y Insurance Company's approval, which would typically involve an assessment of the insured's health status at the time of application. If reinstated, the insurer's liability would recommence from the date of reinstatement.

The dispute arose when the premium payments for January 2007, due by the end of January, were not made. This was because X's bank account, from which premiums were automatically withdrawn, had insufficient funds. The premiums remained unpaid throughout the February 2007 grace period. Subsequently, X applied for reinstatement of the policies, tendering three months' worth of premiums. However, Y Insurance Company refused reinstatement, primarily citing X's health condition at that later time.

X then filed a lawsuit, seeking a court declaration that the insurance contracts were still in existence. X's main argument was that the Lapse Clause, allowing the policies to terminate automatically without a formal demand for payment, was void under Article 10 of the Consumer Contract Act as being unfairly detrimental to consumers.

The Legal Challenge: Is an Automatic Lapse Clause Unfair to Consumers?

The lower courts came to different conclusions:

- The Yokohama District Court (first instance) dismissed X's claim, finding that the contracts had indeed lapsed in accordance with their terms due to non-payment.

- The Tokyo High Court (on appeal) reversed this decision and ruled in favor of X. The High Court found that the Lapse Clause could indeed cause significant and undue detriment to consumer policyholders. It considered the Automatic Premium Loan Clause and the Reinstatement Clause to be insufficient safeguards to mitigate the harshness of an automatic lapse without prior notice or demand. Crucially, the High Court held that Y Insurance Company's actual business practice of sending reminder notices for unpaid premiums (a point Y had raised) was irrelevant to assessing the legal validity of the contractual clause itself. Y Insurance Company appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Conditional Approach to "Lapse Without Notice" Clauses

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 16, 2012, reversed the Tokyo High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court laid out a detailed, conditional framework for assessing the validity of such Lapse Clauses under CCA Article 10.

- Lapse Clause Restricts Consumer Rights (CCA Art. 10 "Front-Half" Satisfied):

The Court first agreed with the High Court on a preliminary point: the Lapse Clause, by providing for the termination of the insurance contract due to non-payment of premiums without requiring the insurer to first issue a formal demand for payment (a saikoku, which is generally a prerequisite for a creditor to cancel a contract due to the debtor's default under Article 541 of the Civil Code), does indeed restrict the rights of the consumer policyholder as compared to the default rules under existing statutes. This satisfied the first part of the test for applying CCA Article 10. - Assessing "Unilateral Harm to Consumer Interests" (CCA Art. 10 "Latter-Half"):

The core of the Supreme Court's analysis focused on whether the Lapse Clause, despite restricting consumer rights, also "unilaterally harms the interests of the consumer in violation of the principle of good faith and fair dealing."- (a) The Detriment of Lacking a Formal Demand: The Court acknowledged that a formal demand for performance under Civil Code Article 541 serves an important function: it alerts the defaulting party to their breach and provides them with an opportunity to rectify it before the contract is cancelled. In the context of insurance contracts – where coverage typically continues even if a premium is missed, until the point of lapse – there is a heightened possibility that a policyholder might genuinely overlook a missed payment or be unaware of an issue like insufficient bank funds. Therefore, a clause that allows the policy to lapse without such a demand does impose a detriment on the policyholder that is "by no means a small one."

- (b) Mitigating Factors within the Policy Terms: The Supreme Court then looked for factors within the insurance contract itself that might mitigate this detriment. It noted:

- The policy clearly stipulated that premiums were due within the "due month."

- Lapse did not occur immediately upon non-payment but only if the default continued through an additional one-month grace period. The Court pointed out that this one-month period was longer than the "reasonable period" that must typically be given in a Civil Code Article 541 demand.

- The Automatic Premium Loan Clause was also a significant consideration. If the policy had accrued sufficient cash surrender value, this clause would prevent an immediate lapse due to a single missed payment, effectively extending coverage.

The Court viewed these provisions as demonstrating "a certain degree of consideration" by the insurer for the protection of policyholder rights even in the event of non-payment.

- (c) The Crucial Role of the Insurer's Actual and Reliable Practice of Sending Reminder Notices: This was the most novel and, for some commentators, controversial part of the Supreme Court's reasoning. Y Insurance Company had argued that its Lapse Clause was intended to operate within the context of an established business practice of sending reminder notices (督促 - tokusoku) to policyholders whose payments were overdue, before their policies actually lapsed.

The Supreme Court held that IF Y Insurance Company, at the time X's contracts were concluded, had a system in place and reliably and consistently executed a practice of sending such pre-lapse reminder notices, then policyholders would normally become aware of their non-payment status.

The Court stated that if such a reliable reminder practice by the insurer was proven, this, in combination with the mitigating factors already present in the policy terms (like the grace period and automatic premium loan clause), would mean the Lapse Clause could not be deemed to unilaterally harm consumer interests in violation of good faith under CCA Article 10.

- Reason for Remand:

The Supreme Court found that the Tokyo High Court had erred in its interpretation of the grace period (incorrectly seeing it as part of the payment deadline rather than a period after default). More importantly, the High Court had dismissed the relevance of Y Insurance Company's actual reminder practices when assessing the validity of the Lapse Clause. Therefore, the Supreme Court remanded the case back to the High Court to make specific factual findings on whether Y Insurance Company truly had such a reliable and consistently executed system of sending pre-lapse reminder notices to policyholders at the relevant times.

Justice Sudo's Dissenting Opinion: Why "Practice" Isn't a Sufficient Safeguard

Justice Masahiko Sudo issued a dissenting opinion, disagreeing with the majority's reliance on the insurer's non-contractual practices. His key arguments, which resonated with some legal commentators, included:

- Lack of Legal Guarantee: A mere business practice of sending reminders, if not contractually stipulated in the policy terms, offers no legal guarantee to the policyholder. The insurer could change or inconsistently apply this practice (e.g., due to cost-cutting) without any legal recourse for the consumer. The protection it offers is factual, not legal.

- Insufficiency of Other "Mitigating Factors":

- The one-month grace period, while seemingly longer than a typical Civil Code demand period, only becomes meaningful once the policyholder is aware of the default. If a reminder notice is delayed, the actual time available to rectify the default can be very short.

- The Automatic Premium Loan Clause is contingent on the policy having accrued sufficient cash surrender value. For relatively new policies, like X's, this feature might offer no protection at all if the cash value is zero or negligible.

- Primacy of Legal Rights: The dissent argued that the legal right to receive a formal demand for payment under Civil Code Article 541, which provides a clear opportunity to avoid contract termination, is a fundamental protection. The combination of a contractual grace period of uncertain practical utility and a non-binding reminder practice by the insurer does not provide an equivalent level of legal security to the policyholder.

- Conclusion of the Dissent: Justice Sudo concluded that because the Lapse Clause deprived policyholders of the legally guaranteed protection of a formal demand before their vital insurance coverage was terminated, it did indeed unilaterally harm consumer interests in violation of good faith and should be deemed void under CCA Article 10. He emphasized that the focus should be on the legally binding terms of the contract itself, not on the insurer's discretionary and potentially variable operational practices.

Implications of the Ruling and the Outcome on Remand

The Supreme Court's decision did not give a blanket approval to all "lapse without notice" clauses in insurance policies. Instead, it established a conditional validity: such clauses might be upheld under CCA Article 10 if the insurance policy itself contains certain mitigating features (like a clearly defined grace period and an automatic premium loan provision, where applicable) AND if the insurer can prove that it had, at the relevant time, a demonstrably reliable and consistently executed business practice of sending pre-lapse reminder notices to policyholders.

This places a significant evidentiary burden on insurers seeking to enforce such clauses. They may need to demonstrate not only that their policy wordings offer some safeguards but also that their internal operational systems for warning policyholders about impending lapse are robust, consistently applied, and were in effect when the consumer's contract was formed.

As noted in the provided PDF commentary, the Tokyo High Court, upon re-examining the case on remand (in a judgment dated October 25, 2012), made factual findings that Y Insurance Company did indeed have a reliable and consistently executed system of sending such reminder notices. Based on this factual determination, and following the Supreme Court's directive, the High Court on remand concluded that the Lapse Clause in X's policies was not void under CCA Article 10. Consequently, X's claim for a declaration that the insurance policies were still in existence was ultimately dismissed. This outcome underscores the critical importance of the factual findings regarding the insurer's actual operational practices in applying the Supreme Court's conditional test.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2012 judgment in this insurance lapse case provides a nuanced, if somewhat controversial, framework for assessing "lapse without notice" clauses under Japan's Consumer Contract Act. While acknowledging the potential detriment to consumers from losing insurance coverage without a formal demand for payment, the Court allowed for the validity of such clauses if a combination of contractual safeguards and reliably executed, albeit non-contractual, reminder practices by the insurer are in place. The decision highlights the judiciary's willingness to consider the broader operational context of consumer contracts but also sparks ongoing debate about the extent to which non-binding business practices should influence the legal assessment of a contractual term's fairness, particularly when fundamental consumer protections are at stake.