Ink and Interpretation: Japanese Supreme Court Rules Tattooing is Not a "Medical Act"

Tattooing, an ancient practice with deep cultural roots and growing global popularity, has often occupied a grey area in legal definitions, particularly concerning its intersection with medical regulations. In Japan, this ambiguity led to a pivotal case where a tattooist was prosecuted for allegedly violating the Medical Practitioners' Act. On September 16, 2020, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision (Heisei 30 (A) No. 1790), ruling that performing tattoos does not constitute "medical practice" (igyō) as defined by the Act, thereby acquitting the tattooist.

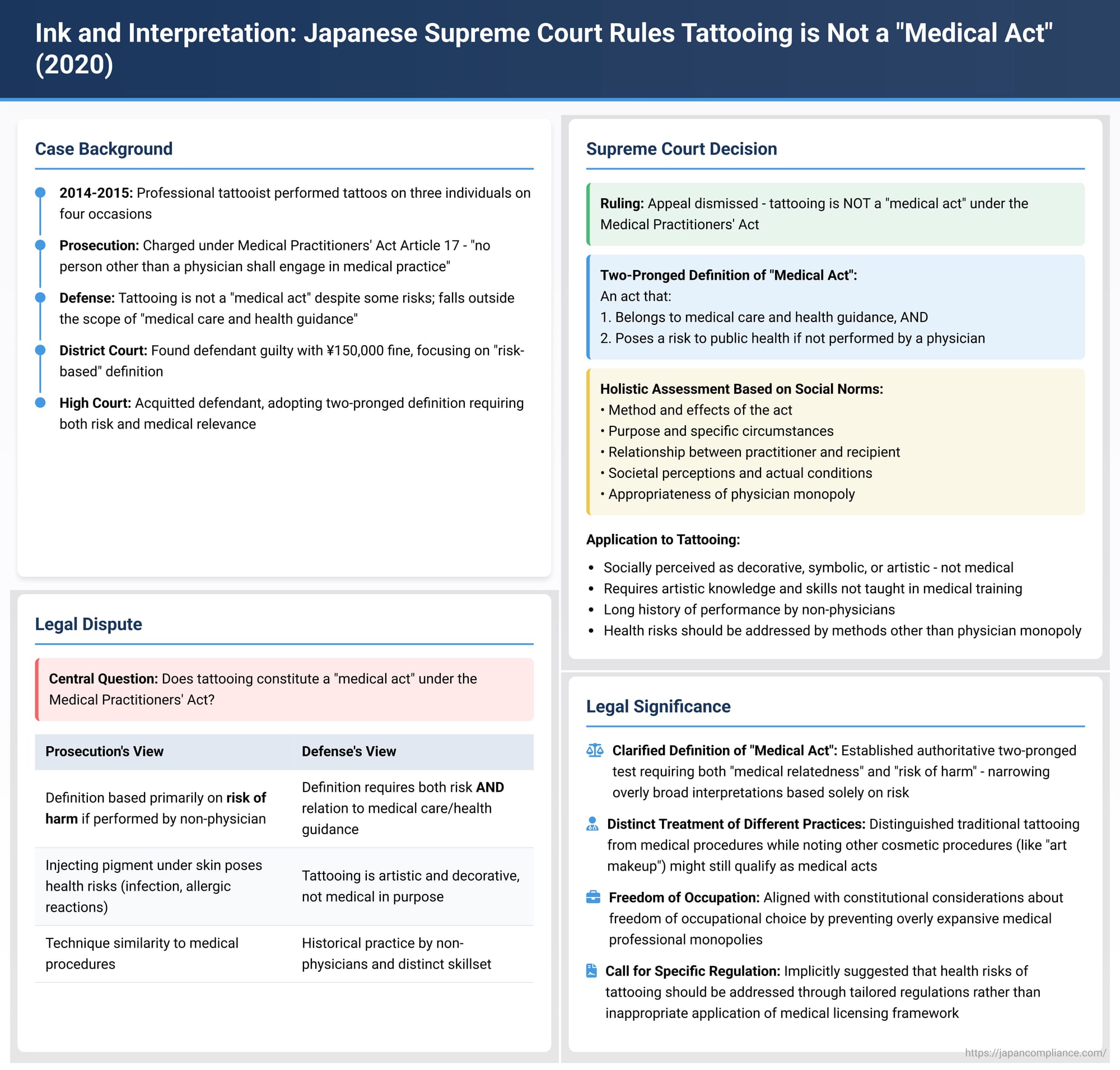

The Case: A Tattooist Charged Under the Medical Practitioners' Act

The defendant, a professional tattooist, was charged with violating Article 17 of the Medical Practitioners' Act, which stipulates that "no person other than a physician shall engage in medical practice." The prosecution alleged that the defendant, despite not being a licensed physician, had performed tattooing—defined as using a needle-equipped tool to inject pigment into the skin—on three individuals as a business on four occasions between July 2014 and March 2015.

The core legal question was whether tattooing falls under the definition of a "medical act" (ikōi), the performance of which as a business constitutes "medical practice" reserved exclusively for physicians. The defense argued that a "medical act" must not only pose a potential risk to public health if not performed by a physician but must also inherently pertain to "medical care and health guidance." They contended that tattooing, while carrying risks, did not meet the latter criterion, and that punishing it under the Medical Practitioners' Act would infringe upon constitutional rights, including freedom of occupation.

The Legal Journey: Conflicting Lower Court Views

The lower courts presented contrasting interpretations:

- First Instance (Osaka District Court): The District Court found the defendant guilty, imposing a fine of 150,000 yen. Its decision hinged on a definition of "medical act" that primarily emphasized the risk of harm to public health and hygiene if not performed by a physician. It deemed the "medical relatedness" aspect unnecessary, concluding that tattooing, due to potential skin damage and other health risks, fell within this risk-based definition.

- Appellate Court (Osaka High Court): The High Court overturned the conviction and acquitted the defendant. It adopted a two-pronged definition, arguing that a "medical act" must not only carry a potential health risk but must also be an act that pertains to medical care and health guidance. The High Court found that tattooing, despite its risks, lacked this essential "medical relatedness" and therefore did not constitute a medical act under the statute. It also noted that defining "medical act" solely by risk could raise constitutional questions regarding freedom of occupational choice.

The prosecutor appealed the acquittal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (September 16, 2020): Tattooing is Not a Medical Act

The Supreme Court dismissed the prosecutor's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's acquittal of the tattooist. The Court's decision provided a crucial clarification on the definition of "medical act."

Two-Pronged Definition of "Medical Act" Confirmed:

The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's two-part test, stating:

"The Medical Practitioners' Act establishes medical care and health guidance as the duty of physicians, and aims to contribute to the improvement and promotion of public health and thereby ensure the healthy lives of the people by physicians fulfilling this duty (Article 1)... In light of these provisions... Article 17 is understood as a provision intended to prevent public health and hygiene dangers that arise when unqualified persons, who are not physicians, perform medical care and health guidance, which is the duty of physicians. Therefore, it is appropriate to interpret a medical act as an act among those belonging to medical care and health guidance, which poses a risk to public health and hygiene if not performed by a physician." Both elements are necessary.

Holistic Assessment Based on Social Norms (Shakai Tsūnen):

The Court elaborated on how to determine if an act qualifies as a "medical act":

"When judging whether a certain act constitutes a medical act, it is necessary to examine the method and effects of said act. However, even for acts with the same method and effects, whether they belong to medical care and health guidance, or whether they pose a risk to public health and hygiene, can differ depending on their purpose, the relationship between the practitioner and the recipient, the specific circumstances under which the act is performed, etc. Furthermore, since Article 17 of the Medical Practitioners' Act is a provision intended to prevent public health and hygiene dangers by means of granting physicians a monopoly over medical acts, it is necessary to also consider the actual conditions of said act, societal perceptions thereof, etc., in order to judge the permissibility and appropriateness of physicians performing it exclusively. Thus, regarding whether a certain act constitutes a medical act, it is appropriate to make a judgment in light of social common sense, after considering not only the method and effects of said act, but also its purpose, the relationship between the practitioner and the recipient, the specific circumstances under which it is performed, its actual conditions, societal perceptions thereof, etc."

Applying the Definition to Tattooing:

Based on this comprehensive approach, the Supreme Court found that tattooing did not meet the criteria of a "medical act":

- Societal Perception and Purpose: "The act of tattooing... is something that has been perceived as a social custom with decorative, symbolic, or artistic significance, and has not been considered an act belonging to medical care and health guidance."

- Required Skills are Artistic, Not Medical: "Moreover, the act of tattooing is an act that requires knowledge and skills related to art, etc., which are different from medicine, and it is not envisioned that these knowledge and skills are acquired in the process of obtaining a medical license, etc."

- Historical Practice by Non-Physicians: "Historically, there has been a long-standing reality of tattooists without medical licenses performing it, and a situation where physicians exclusively perform it is difficult to imagine."

- Conclusion on Tattooing: "Under these circumstances, the defendant's actions, in light of social common sense, are difficult to recognize as acts belonging to medical care and health guidance, and should be said not to constitute medical acts."

Addressing Health Risks Associated with Tattooing

The Supreme Court acknowledged the potential health risks linked to tattooing. However, it concluded that these risks should be addressed differently: "Regarding the public health and hygiene dangers associated with the act of tattooing, there is no choice but to prevent them by methods other than having physicians perform it exclusively." This points towards the need for specific regulations, industry standards, or other public health measures tailored to the practice of tattooing itself.

Significance of the Decision

This Supreme Court decision carries considerable weight:

- Clarification of "Medical Act": It provides an authoritative, two-pronged definition of "medical act," emphasizing that both "medical relatedness" and "risk of harm if not done by a physician" are necessary components. This moves away from a potentially overbroad interpretation based solely on risk, a view that had gained traction in some administrative interpretations and lower court rulings in the past. The Court's grounding of this interpretation in the overall purpose of the Medical Practitioners' Act is considered persuasive.

- Impact on Other Practices: The ruling may necessitate a re-evaluation of other practices that lie at the intersection of aesthetics, wellness, and potential health risks. The commentary notes that "art makeup" (cosmetic tattooing for eyebrows, eyeliner, etc.) was still considered a medical act by the High Court in this case, and the Supreme Court's judicial research official's commentary on this decision also suggested art makeup would likely still be considered a medical act. This suggests that the specific historical context and societal perception of decorative tattooing played a significant role in the Supreme Court's reasoning, and the ruling's direct applicability to other procedures will require careful consideration of their specific circumstances.

- Freedom of Occupation Considerations: Although the Supreme Court did not explicitly invoke constitutional rights as the primary basis for its decision, its reasoning aligns with concerns about freedom of occupational choice. Defining "medical practice" too broadly solely based on risk could unduly restrict legitimate professions that, while carrying some risks, are not inherently medical in nature.

- Call for Specific Regulation (Implicit and Explicit): The decision, particularly when read with Justice Kusano's supplementary opinion and the High Court's remarks, effectively signals that if the health risks associated with tattooing are deemed to require governmental oversight, the appropriate path is through new, specific legislation or regulations for the tattooing industry, rather than attempting to shoehorn it into the existing framework of medical licensing designed for physicians.

A Note on Other Potential Legal Issues

In his supplementary opinion, Justice Koichi Kusano pointed out that the act of tattooing inherently involves causing injury to the client's body. Therefore, depending on the specific content, method, hygiene standards, and outcome of the procedure, tattooing could potentially still give rise to criminal charges for offenses such as assault or causing bodily injury under separate articles of the Penal Code, even if the client consents (as consent does not always negate criminal liability for injury in Japanese law).

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 2020 decision in the tattooist's case is a landmark ruling. It clarifies that tattooing, recognized for its artistic, decorative, and symbolic roles in society, does not fall under the definition of "medical acts" restricted to licensed physicians by the Medical Practitioners' Act. While acknowledging the potential health risks involved, the Court has indicated that these are matters to be addressed through specific regulatory measures tailored to the tattooing practice itself, rather than through an expansive interpretation of medical law. This judgment emphasizes the importance of considering historical context, societal understanding, and the specific nature of an activity when defining the boundaries of professional monopolies, especially when fundamental freedoms like occupational choice are implicated.