Inheriting Joint and Several Debt in Japan: The Supreme Court's "Divided Succession" Principle

Date of Judgment: June 19, 1959

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 32 (o) No. 477 (Claim for Loan Repayment)

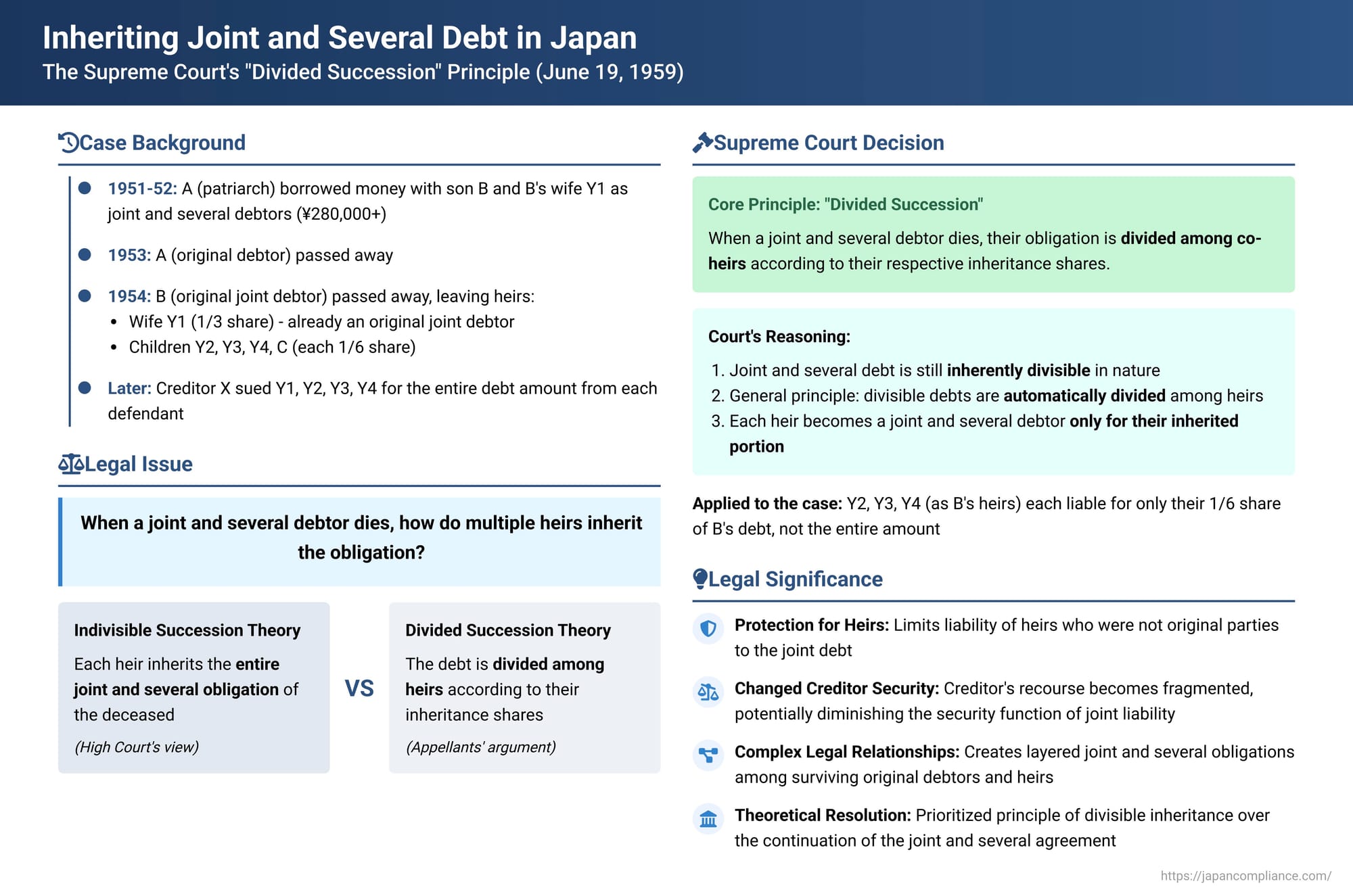

When an individual who is a party to a joint and several debt (連帯債務 - rentai saimu) passes away leaving multiple heirs, a critical question arises: how is this debt inherited? Does each heir become responsible for the entirety of the deceased's obligation, reflecting the original "joint and several" nature? Or is the debt divided among the heirs according to their respective inheritance shares, with each heir then liable only for their inherited portion? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this fundamental issue in its decision on June 19, 1959, establishing the principle of "divided succession" for such inherited debts.

Facts of the Case: A Family Debt and Subsequent Inheritances

The case involved a series of loans within a family context and the subsequent deaths of key debtors.

- The Original Debt: A, the patriarch of a family, had borrowed money on several occasions from the predecessor of X (the plaintiff/creditor) for purposes such as sending allowances to his grandchildren Y2, Y3, and Y4, who were studying in Tokyo. In Showa 26 (1951), these debts were consolidated. A promissory note for over ¥180,000 was issued to X's predecessor, with A as the primary borrower. A's son, B, and B's wife, Y1, were effectively made joint and several debtors. While B and Y1's children (Y2, Y3, Y4) were also listed on the note as joint borrowers, the courts later found they were not knowingly parties to this initial agreement, and the binding contractual effect was limited to A, B, and Y1. A subsequent loan agreement in Showa 27 (1952), primarily for unpaid interest on the first loan (treated as a quasi-loan for consumption), brought the total principal owed to over ¥280,000 under similar joint and several terms for A, B, and Y1.

- Deaths of Original Debtors: A passed away in Showa 28 (1953). Subsequently, A's son B passed away in Showa 29 (1954).

- B's Heirs: Upon B's death, his legal heirs were his wife, Y1 (who was already an original joint and several debtor), and their children, Y2, Y3, Y4, and another child, C. Under the statutory inheritance shares applicable at the time (pre-1980 Civil Code amendment), Y1's share as B's spouse was 1/3, and each of the four children (Y2, Y3, Y4, C) inherited a 1/6 share of B's estate (including his debts).

- The Lawsuit: As the loan remained unpaid, X (the successor to the original creditor) filed a lawsuit against Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4, seeking repayment of the full outstanding amount (over ¥280,000) from each of them.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance Court: This court found that Y2, Y3, and Y4 were not bound as original joint borrowers. However, it held Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4 liable as heirs of B, ordering each to pay a portion of B's debt divided according to their respective inheritance shares.

- High Court: On appeal, the High Court affirmed Y1's status as an original contracting party (joint and several debtor). Critically, it adopted the legal interpretation that when a joint and several debtor dies, their heirs each inherit the obligation to pay the full amount of the deceased's joint and several debt (this is known as the "indivisible succession theory"). However, because the creditor X had not appealed the first instance judgment's award (which was based on divided shares), the High Court, despite its differing legal view, ultimately upheld the first instance judgment's outcome which had ordered payments of divided shares.

- Appeal to the Supreme Court by Y1-Y4: Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4 appealed to the Supreme Court. They argued that inherited debts, including those arising from a joint and several obligation of the deceased, should be divided among the heirs according to their inheritance shares, thereby reducing their individual liability.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Establishing "Divided Succession"

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's judgment. It dismissed Y1's appeal but found in favor of Y2, Y3, and Y4, remanding their cases for recalculation of their liabilities.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of Joint and Several Debt: The Court first described joint and several debt as an obligation where multiple debtors are each independently liable for the full performance of the entire debt. These individual obligations are interconnected to achieve the common goal of securing the creditor's claim and ensuring satisfaction. However, the Court emphasized that, like ordinary monetary debts, a joint and several debt is still inherently divisible in nature.

- General Principle of Inheriting Debts: The Court then referred to established precedents (a Daishin'in (Great Court of Cassation) decision from Showa 5.12.4 and a Supreme Court decision from Showa 29.4.8 ) which held that when a debtor dies leaving multiple heirs, the deceased's monetary debts and other divisible obligations are, by operation of law, automatically divided among the co-heirs. Each co-heir succeeds to these debts according to their respective inheritance share.

- Application to the Inheritance of Joint and Several Debt: Combining these two points, the Supreme Court concluded:

- When one of several joint and several debtors dies, their heirs inherit the deceased debtor's obligation as divided portions according to their individual inheritance shares.

- Each heir, having succeeded to their respective divided portion of the debt, then becomes a joint and several debtor only to the extent of that inherited divided portion. They stand in this limited joint and several capacity alongside the original, surviving joint and several debtors (if any) and alongside other heirs who have similarly inherited their respective portions.

Application to the Appellants:

- Y1 (Wife of B): The Supreme Court affirmed that Y1, having been an original contracting party to the joint and several loan agreement alongside A and B, remained liable for the full amount of the debt, independent of her status as an heir of B. Her appeal was therefore dismissed. (Her inheritance of a share of B's debt was, in her case, subsumed by her pre-existing full liability).

- Y2, Y3, Y4 (Children of B): These appellants were found liable only in their capacity as heirs of B (who was an original joint and several debtor). The High Court had erred in its legal interpretation by stating that they would inherit B's joint and several obligation indivisibly (i.e., each being liable for the full amount B owed). Because the High Court's reasoning was based on this incorrect "indivisible succession" theory, it would have, in principle, imposed an excessive liability on Y2, Y3, and Y4. Therefore, their appeals were considered valid, and their cases were remanded for a recalculation of their liabilities based on the "divided succession" principle – meaning each would be liable for their 1/6 share of B's original joint and several debt.

Legal Principles and Significance of the Ruling

This 1959 Supreme Court judgment is a foundational decision in Japanese inheritance law, establishing the "divided succession theory" (分割承継説 - bunkatsu shōkeisetsu) for how joint and several debts are inherited.

- Adoption of Divided Succession: The Court clearly rejected the "indivisible succession theory" (不分割承継説 - fubunkatsu shōkeisetsu), which would have made each heir liable for the entirety of the deceased joint and several debtor's obligation.

- Emphasis on the Divisible Nature of Monetary Debt: The core of the Court's reasoning lies in the inherently divisible nature of monetary obligations. It applied the general principle that divisible debts of a deceased person are automatically split among heirs according to their inheritance shares.

- Protection for Heirs (Not Original Co-debtors): This ruling generally limits the liability of heirs who were not themselves original parties to the joint and several agreement. Instead of being burdened with the full weight of the deceased's obligation, their liability is confined to their proportional inherited share of that obligation.

- Impact on the Creditor's Security Function: The primary argument in favor of the "indivisible succession theory" (which was supported by many legal scholars) was the preservation of the creditor's security. Joint and several liability is designed to protect the creditor by allowing them to claim the full amount from any one debtor, thus mitigating the risk of insolvency of other debtors. The "divided succession" approach adopted by the Supreme Court means that when a joint and several debtor dies, the creditor can no longer look to that deceased debtor's "slot" for the full amount from each of their heirs individually. Instead, they must pursue each heir for their respective divided portion. While the heirs collectively cover the deceased's original share, the creditor's recourse becomes fragmented. The Supreme Court's decision implicitly accepts that the death of a co-debtor may inevitably alter the creditor's security, prioritizing the principle of divided succession for inherited debts over the undiminished continuation of the original security arrangement against each heir of a single deceased debtor.

- Increased Complexity of Legal Relationships: The "divided succession theory" can lead to more complex legal relationships, especially if multiple joint and several debtors pass away and their obligations are inherited by different sets of heirs. Each heir of a deceased joint and several debtor becomes liable for their inherited fraction, and they are jointly and severally liable for that fraction with any surviving original joint and several debtors and with other heirs who have similarly inherited portions of other deceased co-debtors' liabilities. The PDF commentary provides an illustration: if M and N are joint and several debtors for ¥10 million, and M dies leaving heirs m1 and m2 (each inheriting 1/2 of M's ¥5 million share of debt), and N later dies leaving heirs n1 and n2 (each inheriting 1/2 of N's ¥5 million share of debt), the creditor needs to strategically combine claims. For example, claiming ¥5M from m1 and ¥5M from n1 might lead to full recovery, but claiming from m1 and m2 only covers M's original share, not the full ¥10M. This complexity requires careful navigation by creditors.

- Alternative Creditor Protections (Historical Context): The PDF commentary mentions that creditors might have historically had other (though perhaps limited) avenues for protection, such as requesting a formal separation of the deceased's estate for the satisfaction of debts (財産分離請求 - zaisan bunri seikyū) or, under pre-2017 Civil Code revisions, relying on specific contractual agreements to make an obligation indivisible (a mechanism since abolished). The abolition of the latter potentially weakens one of the arguments that might have indirectly supported the divided succession theory by removing an alternative creditor safeguard.

- Theoretical Underpinnings – Divisibility vs. Contractual Intent: The core of the debate between the "divided" and "indivisible" succession theories lies in a tension: should the law prioritize the "joint and several agreement" (連帯特約 - rentai tokuyaku) made by the original debtors (which subjected them to full liability), thereby transmitting this full-liability status indivisibly to each heir? Or should it prioritize the general legal principle that divisible inherited obligations (like monetary debts) are automatically divided among heirs? The Supreme Court, in this 1959 decision, opted for the latter when determining the extent of liability for heirs who were not original co-debtors.

Conclusion

The 1959 Supreme Court decision established a crucial principle in Japanese inheritance law: when a joint and several debtor dies, their obligation is inherited by their co-heirs in divided shares. Each heir then becomes a joint and several debtor, but only to the extent of their inherited portion of the deceased's debt, alongside any surviving original joint and several debtors. While this "divided succession theory" can introduce complexity into the resulting legal relationships and may alter the creditor's original security landscape, it aligns with the broader principle of how divisible debts are generally treated upon inheritance, offering a degree of protection to heirs from being unexpectedly burdened with the entirety of a deceased family member's joint and several liability. This ruling continues to be a foundational element in understanding the interplay between joint and several obligations and the principles of inheritance in Japan.