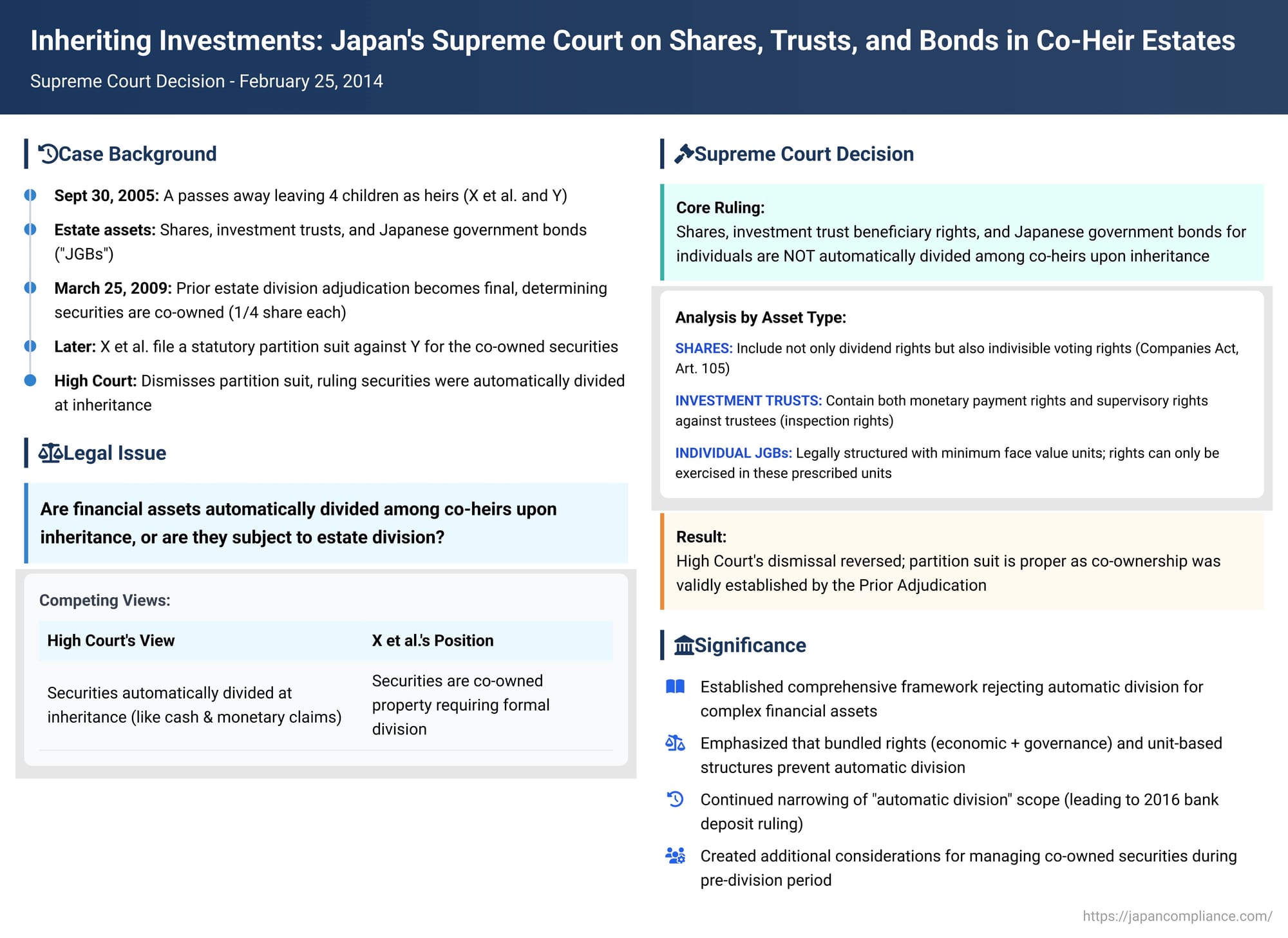

Inheriting Investments: Japan's Supreme Court on Shares, Trusts, and Bonds in Co-Heir Estates

Date of Judgment: February 25, 2014

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. Heisei 23 (Ju) No. 2250 (Claim for Partition of Co-owned Property)

When an individual passes away leaving behind financial assets such as shares of stock, investment trust beneficiary rights, or government bonds, and there are multiple heirs, a critical question arises: are these assets automatically divided among the co-heirs according to their inheritance shares at the moment of death? Or do they become co-owned property that requires a formal estate division process to determine their ultimate allocation? The Supreme Court of Japan provided comprehensive guidance on this issue in its decision on February 25, 2014, clarifying that such financial instruments generally do not undergo automatic division and are instead subject to the estate division process.

Facts of the Case: A Dispute Following an Estate Division Adjudication

The case involved four heirs and a dispute over the partition of various financial securities.

- The Deceased and Heirs: A passed away on September 30, 2005. The legal heirs were A's four children: X et al. (three individuals who were the plaintiffs/appellants) and Y (the defendant/appellee). Each heir had a statutory inheritance share of 1/4.

- The Disputed Securities: The estate included Japanese government bonds for individuals ("JGBs"), investment trust beneficiary rights (both domestic settlor-directed trusts and foreign investment trusts, collectively "Investment Trusts"), and shares of stock ("Shares"). These are collectively referred to as "the Disputed Securities."

- Prior Estate Division Adjudication: Y had previously initiated estate division proceedings concerning A's estate. In these proceedings, a judicial adjudication (the "Prior Adjudication") was made, which became final and binding on March 25, 2009. This Prior Adjudication determined, among other things, that the Disputed Securities were to be co-owned by X et al. and Y, with each party holding a 1/4 share in these assets.

- The Current Lawsuit for Statutory Partition: Based on the state of co-ownership established by this final Prior Adjudication, X et al. subsequently filed a new lawsuit against Y. In this new suit, X et al. sought a statutory partition (共有物分割 - kyōyūbutsu bunkatsu, under Article 256, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code) of the Disputed Securities, aiming to divide these co-owned assets physically or by other means prescribed by law.

- High Court's Dismissal of the Partition Suit: The High Court dismissed X et al.'s partition suit as legally improper. The High Court reasoned that financial assets like the Disputed Securities should be considered to have been automatically divided among the co-heirs according to their respective 1/4 inheritance shares at the moment of A's death. According to this view, the Prior Adjudication was merely a confirmation of this pre-existing, automatically divided ownership, rather than an act that created a state of co-ownership. Therefore, the High Court concluded, there was no co-owned property (in the sense required for a statutory partition suit) that could be the subject of a new partition claim.

- Appeal to the Supreme Court: X et al. appealed the High Court's dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Reversing the High Court

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings on the partition claim. The Supreme Court meticulously examined each category of the Disputed Securities and concluded that none of them were subject to automatic division upon inheritance.

Core Principle: Inherited shares, investment trust beneficiary rights, and individual JGBs are not automatically divided among co-heirs at the time of inheritance. Instead, they become subject to quasi co-ownership (準共有 - jun-kyōyū) by the heirs, and their final allocation must be determined through the estate division process.

The Court's reasoning for each type of security was as follows:

- Shares of Stock:

- Shares represent a legal status of being a shareholder in a company. This status encompasses not only economic rights (自益権 - jiekiken), such as the right to receive dividends (Companies Act, Art. 105(1)(i)) and distributions of residual assets (Art. 105(1)(ii)), but also administrative or participatory rights (共益権 - kyōekiken), such as the right to vote at general shareholders' meetings (Art. 105(1)(iii)).

- The Supreme Court held that, considering the nature and content of the rights included in shares, particularly the non-economic participatory rights which are not inherently divisible in proportion to inheritance shares, co-inherited shares are not automatically divided upon inheritance. The Court referenced its prior case law (e.g., Supreme Court, Showa 45.1.22 - January 22, 1970) that supported this view.

- Investment Trust Beneficiary Rights:

- Domestic Settlor-Directed Investment Trusts: The Court noted that beneficiary rights in such trusts (as defined in Article 2, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Investment Trusts and Investment Corporations) are typically denominated in units. These rights include not only claims for monetary payments (such as redemption proceeds and profit distributions under Article 6, Paragraph 3 of the same Act) but also supervisory rights exercisable against the trustee, like the right to inspect trust-related books and records (Article 15, Paragraph 2 of the same Act). Because these beneficiary rights include elements that are not simply for divisible monetary payments (i.e., the supervisory functions), the Court concluded that they are not automatically divided upon inheritance.

- Foreign Investment Trust Beneficiary Rights: These are rights in trusts established under foreign laws that are analogous to domestic investment trusts (as per Article 2, Paragraph 22 of the Act on Investment Trusts and Investment Corporations). While the specific details of the foreign investment trust rights in this case were not entirely clear from the record, the Court found that given their similarity to domestic investment trusts, there was sufficient basis to conclude that these rights, too, are not automatically divided upon inheritance and could be treated similarly to domestic ones.

- Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs for individuals):

- The JGBs in question were "individual JGBs" as prescribed by ministerial ordinance. The ordinance stipulates a minimum face value for these bonds (e.g., ¥10,000), and records of ownership in the book-entry transfer system are made in multiples of this minimum amount (Ordinance, Art. 3). Furthermore, mid-term redemption of these JGBs through purchase by a handling institution is also understood to be based on this unit amount (Ordinance, Art. 6).

- Given these legal provisions that establish a defined unit for the rights and do not envisage the exercise of rights for amounts less than this unit, the Supreme Court concluded that co-inherited individual JGBs are not automatically divided upon inheritance.

Consequences for the Partition Suit:

The Supreme Court reasoned that if the Disputed Securities were not automatically divided at the time of A's death, then their ultimate ownership and distribution among the heirs had to be determined through the estate division process.

Therefore, the Prior Adjudication (which had determined that X et al. and Y co-owned the Disputed Securities in 1/4 shares each) had validly established a state of quasi co-ownership for these assets.

As a result, the subsequent lawsuit filed by X et al. seeking a statutory partition of these co-owned Disputed Securities was a legally proper and admissible claim. The High Court's dismissal was thus erroneous.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 2014 Supreme Court decision has significant implications for how financial assets are handled in Japanese inheritance cases:

- Comprehensive Rejection of Automatic Division for Key Financial Assets: The judgment provides a clear and unified Supreme Court stance against the automatic division of commonly inherited financial instruments like shares, investment trusts, and individual-type JGBs. It firmly places them in the category of assets requiring formal estate division.

- Emphasis on the Nature of the Rights: A consistent thread in the Court's reasoning is its focus on the content and nature of the rights embodied by each financial product. If these rights include non-divisible elements (such as participatory rights in shares or supervisory rights in investment trusts) or if the legal or regulatory framework prescribes indivisible units (as with the JGBs), then the principle of automatic division is negated.

- Evolution from Earlier Views on Divisible Claims: Legal commentary notes that this decision represented a significant step in the evolving jurisprudence concerning inherited assets. While very simple monetary claims (like a tort damages claim, as per a Showa 29 [1954] ruling) were traditionally seen as automatically divisible, and for a long time, bank deposits were also treated this way (until a major Supreme Court Grand Bench decision in 2016, after this 2014 securities case), the trend has been to narrow the scope of "automatic division." This 2014 ruling on securities strongly signaled that more complex financial assets, with bundled rights or unit-based structures, are not amenable to such automatic splitting.

- Implications for Co-ownership and Exercise of Rights Post-Inheritance but Pre-Division: For assets like shares that become co-owned by heirs, their management and the exercise of shareholder rights (e.g., voting) before formal division are governed by rules applicable to co-ownership. Typically, this involves designating a representative to exercise such rights, often determined by the majority vote based on the value of the co-owned shares. The commentary also points to ongoing academic discussion regarding the protection of minority co-heirs' interests in such scenarios.

- The Broader Trend Towards Comprehensive Estate Division: This 2014 ruling, viewed alongside the subsequent 2016 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision that subjected bank deposits to estate division, reflects a clear judicial preference for including a wider range of financial assets within the formal estate division process. This approach allows for a more holistic and equitable distribution of the entire estate, especially when factors such as special benefits received by some heirs or contributions made by others need to be taken into account to achieve fairness.

- Concerns and Legislative Responses: While promoting comprehensive division, the trend away from automatic division also raised concerns about potentially hindering individual heirs' access to inherited assets or their ability to manage them effectively before the often lengthy estate division process concludes. For bank deposits, these concerns led to legislative reforms in 2018 (e.g., Article 909-2 of the Civil Code allowing limited withdrawals). For assets like shares, the issue of how individual co-heirs can meaningfully participate or protect their interests during the co-ownership period remains an important consideration.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2014 decision provides crucial clarity on the co-inheritance of shares, investment trusts, and individual-oriented JGBs. By holding that these financial assets do not automatically divide among heirs but instead become part of the co-owned estate subject to formal division, the Court emphasized the importance of considering the specific nature of the rights involved and the overarching goals of the estate division system. This ruling reinforces the trend towards ensuring that the distribution of complex estates can be handled comprehensively, allowing for equitable adjustments among heirs, and clarifies the proper procedural path for resolving co-ownership of such assets established through an estate division.