Japan Supreme Court Clarifies Survivor Claims to Unpaid Pensions (1995)

Japan’s Supreme Court (1995) ruled survivors must file a separate administrative claim for unpaid pension installments—no automatic succession to the deceased’s lawsuit. Learn the procedure and implications.

TL;DR

- The 1995 Supreme Court held that survivors cannot automatically continue a pension lawsuit after the recipient dies.

- Unpaid installments are not inheritable property; Article 19 of the National Pension Act gives certain relatives a statutory claim.

- Survivors must first file an administrative claim with the pension agency; only after a decision can they litigate.

- The ruling underscores the primacy of administrative procedures in Japan’s social‑security disputes.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: A Dispute Over Pension Suspension and a Plaintiff's Death

- Lower Court Rulings: Lawsuit Terminated

- The Legal Framework: Survivor Rights to Unpaid Pension (NPA Art. 19)

- The Supreme Court's Analysis (November 7, 1995)

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

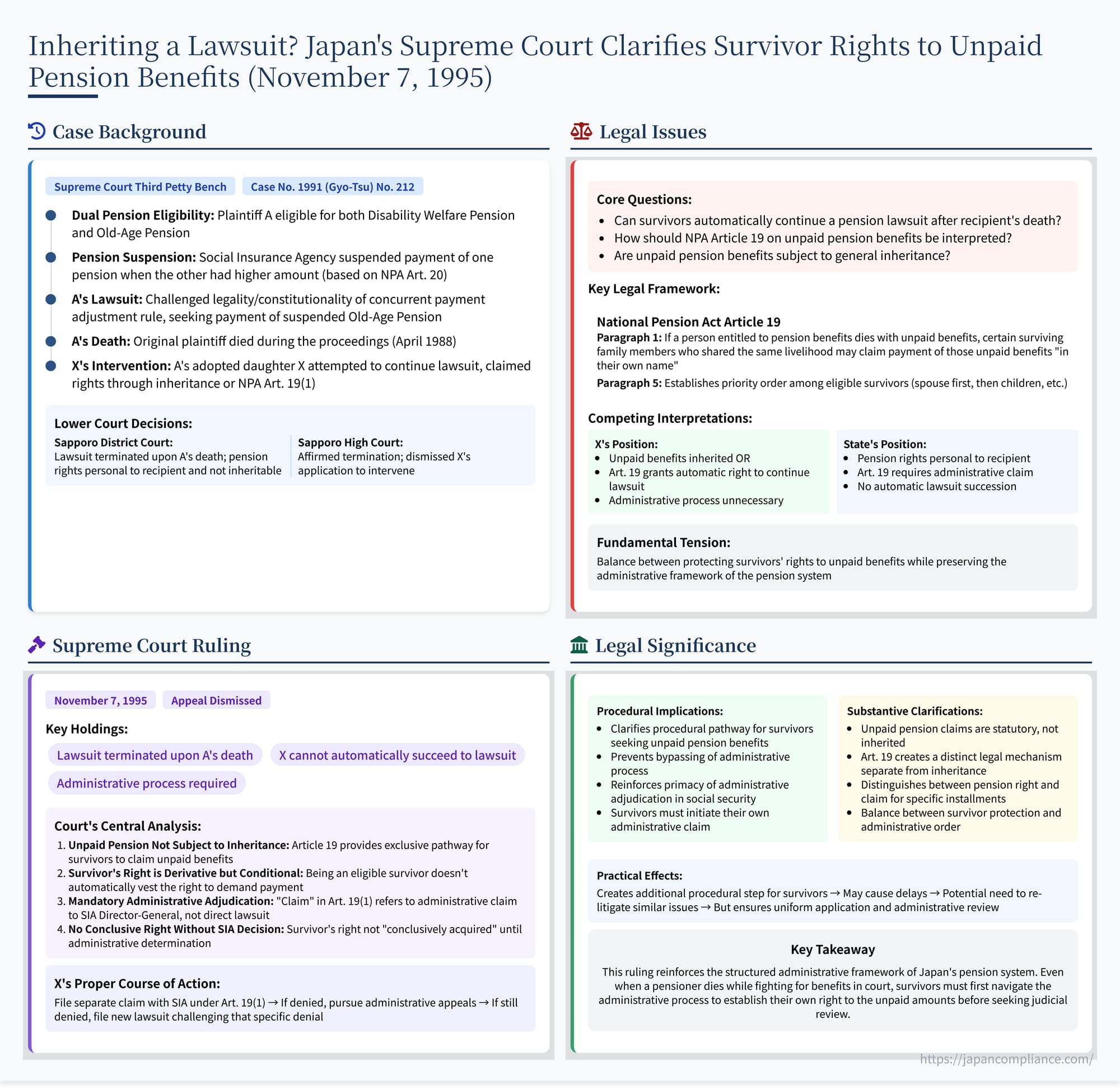

On November 7, 1995, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a ruling addressing a significant procedural question within the country's public pension system: If a person receiving pension benefits dies while pursuing a lawsuit related to those benefits, can their surviving family members automatically step into the deceased's shoes and continue the lawsuit? (Case No. 1991 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 212, "Old-Age Pension Claim, Intervention Application Case"). The Court concluded that survivors cannot automatically succeed to such lawsuits. Instead, they must utilize a specific administrative procedure provided by the National Pension Act to claim any unpaid benefits owed to the deceased, underscoring the distinct nature of survivor claims for unpaid installments compared to both inheritance and the deceased's original pension entitlement.

Factual Background: A Dispute Over Pension Suspension and a Plaintiff's Death

The case originated from a dispute concerning the application of pension rules under Japan's National Pension Act (NPA), specifically the version in effect before the major reforms of 1985:

- Dual Pension Eligibility: The original plaintiff, A, was entitled to receive two types of pensions under the old NPA:

- A Disability Welfare Pension (障害福祉年金 - shōgai fukushi nenkin): A non-contributory pension.

- An Old-Age Pension (老齢年金 - rōrei nenkin): A contributory pension based on A's past premium payments.

- Concurrent Payment Adjustment: The old NPA contained a provision (Article 20) adjusting concurrent pension payments (併給調整 - heikyū chōsei). Generally, an individual eligible for multiple pensions would receive the one with the higher amount, with the other being suspended. A did not submit the required application form to choose which pension to receive.

- Pension Suspension: Consequently, the Social Insurance Agency (SIA) Director-General suspended payment of A's Old-Age Pension for periods when the Disability Welfare Pension amount was higher. Conversely, the Governor of Hokkaido (acting as an administrative agent for certain pension functions at the time) suspended A's Disability Welfare Pension for periods when the Old-Age Pension amount was higher.

- A's Lawsuit: A filed a lawsuit against the State (Y, the appellee), challenging the legality and constitutionality of the concurrent payment adjustment rule (NPA Art. 20) and the resulting suspension of the Old-Age Pension payments. A sought payment of the installments of the Old-Age Pension that had been suspended.

- A's Death and X's Attempt to Continue: While this lawsuit was pending in the court of first instance, A passed away in April 1988. The appellant, X, who was A's adopted daughter, sought to continue the lawsuit. X argued that she had acquired A's right to the unpaid Old-Age Pension installments either through general inheritance laws or, alternatively, directly under NPA Article 19, Paragraph 1. Article 19(1) specifically allows certain surviving family members to claim unpaid pension benefits owed to a deceased recipient. X filed a motion requesting recognition of her succession to A's position as plaintiff. Later, in the appellate stage, X also filed a motion to intervene in the (by then potentially terminated) lawsuit.

Lower Court Rulings: Lawsuit Terminated

The lower courts did not allow X to continue the lawsuit:

- First Instance (Sapporo District Court): Declared that the lawsuit had terminated upon A's death. It denied X's claim of automatic succession, reasoning that the right to receive pension benefits was personal to A (isshin senzoku teki - 一身専属的, meaning non-transferable) and therefore not subject to inheritance. It did not explicitly rule on the effect of NPA Art. 19(1) regarding succession to the lawsuit.

- Second Instance (Sapporo High Court): Upheld the first instance court's declaration that the lawsuit terminated upon A's death. It also dismissed X's application to intervene in the lawsuit as procedurally improper.

X appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Survivor Rights to Unpaid Pension (NPA Art. 19)

The core of the appeal turned on the interpretation and procedural implications of NPA Article 19, which governs unpaid pension benefits after a recipient's death:

- Article 19, Paragraph 1: States that if a person entitled to pension benefits dies, and there are unpaid benefits that should have been paid to the deceased, certain surviving family members – specifically, the spouse, children, parents, grandchildren, grandparents, or siblings who were "sharing the same livelihood" (生計を同じくしていた - seikei o onajiku shite ita) with the deceased at the time of death – may claim payment of those unpaid benefits "in their own name" (jiko no na de).

- Article 19, Paragraph 5: Establishes an order of priority among these eligible survivors (spouse first, then children, etc.).

- Distinct from Inheritance: The provision explicitly allows these specific survivors to claim the funds directly, operating as a statutory mechanism separate from general inheritance law.

The question was whether acquiring the right to claim unpaid benefits under Article 19(1) also meant acquiring the right to automatically continue a lawsuit initiated by the deceased seeking those benefits.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (November 7, 1995)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated November 7, 1995, affirmed the lower courts' conclusion that the lawsuit terminated upon A's death and that X could not automatically succeed to A's position as plaintiff.

1. Unpaid Pension Benefits Not Subject to Inheritance:

The Court first definitively stated that Article 19 provides the exclusive pathway for survivors to claim unpaid pension benefits. The deceased recipient's right to these specific past-due installments does not become part of their inheritable estate. The statute creates a distinct right for specific survivors, separate from inheritance principles. Therefore, X could not claim succession based on general inheritance law.

2. Survivor's Right Under Art. 19(1) is Derivative but Conditional:

The Court acknowledged that the right granted to survivors under Article 19(1) can be understood as being "successively acquired" (承継的に取得 - shōkeitekini shutoku suru) – meaning the survivor's right stems from the deceased's original entitlement. However, the Court held that simply falling within the category of eligible survivors listed in Article 19(1) does not automatically and conclusively vest the right to the funds in that survivor or grant them the immediate ability to demand payment through court action.

3. Mandatory Administrative Adjudication Process:

The crucial part of the Court's reasoning was the necessity of an administrative determination before the survivor's right becomes judicially enforceable.

- The Claim Requirement: Article 19(1) states the survivor "may claim" (seikyū suru koto ga dekiru) payment. The Court interpreted this "claim" by reference to the broader structure of the NPA, particularly Article 16. Article 16 requires that the basic right to receive pension benefits must be determined (saitei - 裁定) by the SIA Director-General based on a claim filed by the potential recipient. This administrative determination process ensures uniform and fair application of eligibility rules and prevents unnecessary disputes.

- Analogy to Basic Pension Claims: While the survivor's claim under Article 19(1) is for specific past-due installments (a "branch right" - 支分権 shibunken) rather than the underlying pension entitlement (a "basic right" - 基本権 kihonken), the Court reasoned that the purpose behind requiring an administrative determination under Article 16 (ensuring uniformity, fairness, legal certainty through official confirmation of eligibility and amounts) applies equally to claims for unpaid benefits by survivors under Article 19.

- Survivor's Claim Directed to SIA: Therefore, the "claim" mentioned in Article 19(1) must be understood as a claim directed to the SIA Director-General, analogous to the initial claim for pension benefits. (The Court noted that implementing regulations already specified this procedure).

- SIA Decision as an Administrative Disposition: The SIA Director-General is expected to respond to this claim. This response, deciding whether the claimant qualifies as the eligible survivor according to the statutory priority and is entitled to the unpaid amount, constitutes an official, public-law confirmation (kōkenteki ni kakunin). As such, this decision falls under the definition of an "administrative disposition concerning benefits" (給付に関する処分 - kyūfu ni kansuru shobun) as used in NPA Article 101(1), making it subject to formal administrative appeals if the claimant disagrees.

4. No Definitive Right or Lawsuit Succession Without SIA Decision:

The Court concluded that until an eligible survivor files a claim under Article 19(1) and receives a formal decision from the SIA Director-General granting payment (shikyū kettei - 支給決定), the survivor has not "conclusively acquired" (kakuteiteki ni shutoku shita) the right to the unpaid pension installments.

Because the right is not conclusively established without this administrative step, the survivor cannot bypass it. They cannot directly sue the State for payment of the unpaid benefits, nor can they automatically take over a lawsuit initiated by the deceased that concerned those benefits.

5. X's Proper Course of Action:

Applying this to the case, the Supreme Court held that X's proper course of action was to file a separate claim for the unpaid Old-Age Pension installments directly with the SIA Director-General under NPA Article 19(1). If that claim were denied, X could then pursue administrative appeals and, if necessary, file her own lawsuit challenging that specific denial. She could not simply step into A's shoes in the ongoing lawsuit challenging the pension suspension rule.

Conclusion on Appeal: Since X could not automatically succeed to A's lawsuit, the lower courts were correct in declaring the lawsuit terminated upon A's death and in denying X's application for intervention. X's appeal was therefore dismissed.

Implications and Significance

This 1995 Supreme Court judgment carries significant procedural weight for beneficiaries of Japan's public pension systems:

- Unpaid Pension Claims are Statutory, Not Inherited: It definitively confirmed that the right of survivors to claim pension installments accrued but unpaid at the time of the recipient's death is governed exclusively by specific statutory provisions (like NPA Art. 19) and is not part of the deceased's inheritable estate.

- Mandatory Administrative Claim for Survivors: The ruling established that even though Article 19 grants survivors a substantive right derived from the deceased, exercising this right requires filing a formal claim with the relevant pension agency (formerly SIA, now largely the Japan Pension Service or relevant mutual aid association) and obtaining an administrative decision.

- Administrative Adjudication is Primary: It underscores the principle that administrative agencies have the primary role in determining eligibility for and amounts of social security benefits. The courts generally only review the legality of the agency's final administrative disposition, rather than allowing direct lawsuits for payment in the first instance (or through succession to a deceased's suit before the survivor's own eligibility is determined administratively).

- Procedural Hurdle for Survivors: While ensuring administrative order and uniformity, this ruling creates a distinct procedural step for survivors. They cannot simply continue a deceased relative's pension-related lawsuit; they must initiate their own administrative claim for the unpaid benefits first. This could potentially lead to delays or require re-litigating similar issues if the agency denies their claim on grounds already being contested in the original lawsuit.

- Distinction Between Benefit Right and Claim for Installments: The judgment implicitly highlights the distinction between the underlying right to receive a pension (which might be the subject of litigation by the pensioner while alive) and the specific right to claim payment of individual installments that become due. Article 19 deals specifically with the latter after the pensioner's death.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 7, 1995 decision clarified that under Japan's National Pension Act, a surviving family member cannot automatically inherit or succeed to a lawsuit initiated by a deceased pension recipient concerning unpaid pension benefits. While NPA Article 19 grants specific survivors the right to claim such unpaid installments "in their own name," separate from inheritance, this right must first be asserted through a formal claim to the administrative agency (the SIA Director-General at the time). Only after the agency makes a decision on the survivor's claim can the matter potentially proceed to court if the survivor disputes the outcome. This ruling reinforces the primacy of administrative procedures in the Japanese social security system for determining entitlement to benefits, even for claims derived from a deceased recipient's rights.

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- Student Disability Pension Gap: Why Japan’s Supreme Court Backed Voluntary Enrollment (2007)

- Japan Supreme Court 2017 Survivor‑Pension Case: Why Age Rules for Widowers Survived an Equality Challenge

- Survivor's Pension Overview – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Public Pension Benefit Structure – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare