Inherited Property, Faulty Registrations, and Third-Party Rights: A 1963 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling and Its Modern Context

Date of Judgment: February 22, 1963 (Showa 38)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 35 (o) No. 1197 (Claim for Registration Cancellation Procedure)

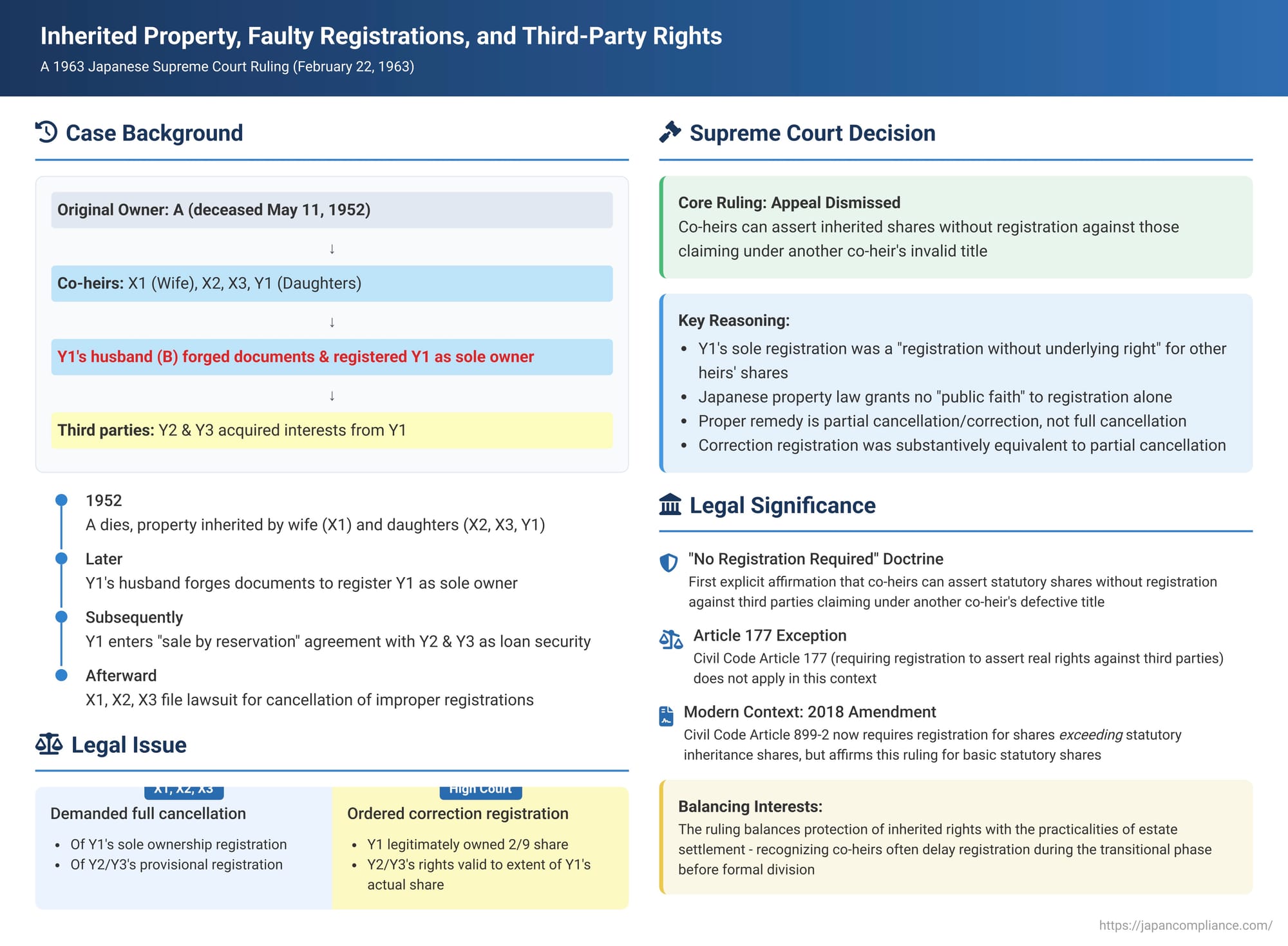

When property is inherited by multiple heirs, it becomes their co-ownership. However, complications frequently arise if one co-heir improperly registers the property in their sole name and then enters into transactions with third parties concerning that property. Can the other co-heirs assert their inherited rights against these third parties if their own shares are not yet registered? And what is the appropriate legal remedy to correct the faulty registration? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed these fundamental questions in a significant decision on February 22, 1963, establishing key principles regarding inheritance and property registration.

Facts of the Case: A Disputed Inheritance and Subsequent Transactions

The case concerned real property ("the Property") originally owned by A, who passed away on May 11, 1952.

- The Co-Heirs: A's legal heirs, who jointly inherited the Property, were his wife X1 (Sada A.), and their three daughters, X2 (Kimiyo A.), X3 (Hatsuko O.), and Y1 (Sakae Y.).

- Fraudulent Sole Ownership Registration: Y1's husband, B, acting without proper authority, forged documents and illicitly procured a registration indicating Y1 as the sole owner of the Property by way of inheritance.

- Transaction with Third Parties: Subsequently, B, initially acting purportedly on Y1's behalf due to her sole ownership registration (and later with Y1's consent), entered into an agreement styled as a "sale by reservation" (売買予約 - baibai yoyaku) for the Property with Y2 (Kikuo T.) and Y3 (Jujo Shoji K.K., a company). This agreement was intended to serve as security for a loan that Y1 (facilitated by B) was seeking from Y2 and Y3. A provisional registration (仮登記 - karitōki) was made on the Property to secure the rights of Y2 and Y3 under this sale by reservation.

- Lawsuit by Other Co-Heirs: X1 (A's wife) and her daughters X2 and X3 (the plaintiffs/appellants) initiated a lawsuit to protect their inherited interests.

- Against Y1 (the daughter in whose sole name the property was improperly registered): They demanded the complete cancellation (抹消登記 - masshō tōki) of her sole ownership registration.

- Against Y2 and Y3 (the third-party acquirers of the interest from Y1): They demanded the complete cancellation of the provisional registration that secured their claim under the sale by reservation.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- First Instance Court: This court ruled entirely in favor of the plaintiffs (X1, X2, X3), ordering the full cancellation of both Y1's sole ownership registration and Y2/Y3's provisional registration.

- High Court: Y1, Y2, and Y3 appealed. The High Court modified the first instance judgment. It reasoned that Y1 genuinely possessed an inherited co-ownership share in the Property. Therefore, the sale by reservation made by Y1 to Y2/Y3 was valid at least to the extent of Y1's actual inherited share. Consequently, completely cancelling Y2/Y3's provisional registration was deemed inappropriate as it could unjustly harm their legitimate rights concerning Y1's valid share. Instead of ordering a full cancellation, the High Court ordered a "correction registration" (更正登記 - kōsei tōki). This correction would amend Y2/Y3's provisional registration to accurately reflect that it pertained only to Y1's actual inherited co-ownership share in the Property (which was determined to be 2/9 based on the applicable inheritance laws at the time – wife 1/3, remaining 2/3 shared equally by three daughters, so each daughter 2/9).

- Appeal to the Supreme Court by Plaintiffs: X1, X2, and X3 appealed the High Court's decision. Their primary ground for appeal was procedural: they argued that the High Court, by ordering a "correction registration" when they had specifically sued for "cancellation registration," had violated the principle that a court cannot grant relief not sought by the parties (a rule then found in Article 186 of the Code of Civil Procedure, now Article 246).

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding Substance Over Form

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1, X2, and X3, thereby affirming the High Court's substantive outcome.

The Supreme Court's reasoning encompassed several key points:

- Co-heirs Can Assert Inherited Shares Without Prior Registration Against Those Claiming Under Another Co-heir's Invalid Title:

The Court held that if one co-heir (like Y1) improperly obtains a registration of sole ownership for an inherited property, and a third party (like Y2 and Y3 in their capacity as purchasers/lenders dealing with Y1) then acquires an interest or registration based on this flawed sole ownership claim, the other co-heirs (X1, X2, X3) can validly assert their own inherited co-ownership shares against both the improperly registered co-heir (Y1) and the third-party acquirer (Y2/Y3). Crucially, they can do so without needing to have previously registered their own inherited shares.

The Court's rationale was twofold:- Y1's sole ownership registration was, to the extent it purported to cover the shares rightfully belonging to X1, X2, and X3, a registration without any underlying legal right (無権利の登記 - mukenri no tōki).

- Japanese property law does not grant "public faith" or indefeasibility of title merely based on registration (登記に公信力なし - tōki ni kōshinryoku nashi). This means that a third party acquiring from someone whose registered title is defective (like Y1's, concerning the other heirs' shares) cannot obtain good title to those portions that the seller did not legitimately own.

- The Proper Remedy: Partial Cancellation (Correction Registration):

In such circumstances, when the rightful co-heirs seek to rectify the property register to reflect the true state of ownership, the appropriate remedy is not a full cancellation of the improperly obtained sole ownership registration or the subsequent third-party registration that relies upon it.

Instead, the rightful co-heirs are entitled to a partial cancellation of these registrations, or what is substantively equivalent, a correction registration. This means the register should be amended to show that the transacting co-heir (Y1) only ever held, and therefore could only validly transact with, her actual inherited share. Consequently, the interest acquired by the third parties (Y2 and Y3) is limited to this actual, validly held share of Y1.

The reason for this is that the improper registrations are, in fact, valid to the extent of the transacting co-heir's (Y1's) actual legitimate share. The other co-heirs (X1, X2, X3) only possess the right to demand the removal of the encumbrance or misrepresentation affecting their own shares. - Procedural Point: Correction Registration as Substantive Partial Cancellation:

Addressing the appellants' procedural argument, the Supreme Court found that the High Court's order for a "correction registration" was, in substance, a "partial cancellation registration." Therefore, the High Court had not impermissibly granted a form of relief that was not sought by the plaintiffs. Instead, it had effectively granted a quantitatively lesser part of the total cancellation the plaintiffs had initially demanded, which is within a court's power.

Legal Principles and Significance: Then and Now

This 1963 Supreme Court decision was a landmark for its time and continues to have relevance, especially when considered alongside subsequent legislative developments.

- "No Registration Required" Doctrine for Co-heirs (Historical Context): This was the Supreme Court's first explicit affirmation that co-heirs do not need to register their directly inherited shares to assert their rights against a third party who derives their claim from another co-heir's defective or incomplete title. This principle is often referred to as arising from the "doctrine of no rights from a void title" (無権利の法理 - mukenri no hōri), essentially stating that one cannot give what one does not have, and registration alone cannot cure a fundamental lack of title against the true owners.

- Implications for Article 177 of the Civil Code (Perfection of Real Rights): In the specific context addressed by this ruling—co-heirs asserting their directly inherited shares against those claiming under another co-heir's flawed title—the general rule of Article 177 of the Civil Code (which typically requires registration to assert changes in real property rights against third parties) was deemed not to apply to defeat the unregistered claims of the rightful co-heirs concerning their statutory shares. The third party in such a situation is not considered a "third party" against whom the original co-heirs need to perfect their directly and automatically acquired inherited shares via registration.

- Justifications and Tensions: The "no registration required" stance for inherited statutory shares can be justified by recognizing that estate co-ownership is often a transitional phase. Heirs might not immediately undertake individual registration procedures, especially since separate registration of individual undivided shares can be complex or procedurally restricted; often, an initial joint inheritance registration is made in the names of all heirs, or full registration awaits the completion of the formal estate division. However, this principle does create a potential risk for third parties who rely on the public register, as they might not easily ascertain the true extent of an individual heir's legitimate share or the status of the estate division.

- The "Elasticity of Co-ownership" Theory (An Alternative View, Not Adopted): The PDF commentary mentions an older academic theory termed "elasticity of co-ownership" (共有の弾力性 - kyōyū no danryokusei). This theory, if adopted, might have led to a different outcome by suggesting that a registered share could "expand" to cover unregistered portions when dealing with third parties. However, this theory faced criticism and was not the basis for the Supreme Court's decision.

- The Impact of the 2018 Civil Code Amendment (Article 899-2): This is a critical modern development discussed in the PDF commentary. The Civil Code was amended in 2018, introducing Article 899-2. This new article stipulates that if an heir acquires rights through inheritance (whether by statutory succession, specific share designation in a will, or an "assign by inheritance" type will) that exceed their basic statutory inheritance share, they cannot assert these excess rights against a bona fide third party unless those rights (or the transfer causing them) are registered.

- Consistency with the 1963 Ruling (for Statutory Shares): Article 899-2, when read inversely, implies that an heir can assert their rights up to their statutory inheritance share against third parties without registration. This aspect of the 1963 Supreme Court ruling—that statutory shares can be asserted without registration against those claiming under another co-heir's faulty title—is therefore consistent with, and arguably reinforced by, the new Article 899-2 for the portion representing the statutory share. The rationale is that the stable succession of statutory shares is fundamental.

- Change for Supra-Statutory Shares: However, Article 899-2 significantly changes the legal landscape for inherited rights that exceed an heir's basic statutory share (e.g., rights derived from a will that gives one heir more than their statutory portion, or from a specific share designation in a will). Prior to this amendment, some Supreme Court precedents (e.g., Heisei 5.7.19 and Heisei 14.6.10) had extended the "no registration required" principle to such supra-statutory acquisitions. Article 899-2 now mandates registration for an heir to assert these rights exceeding their statutory share against third parties, effectively overturning those later precedents on that specific point and enhancing transactional safety concerning such non-statutory augmentations of shares.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1963 decision established important principles regarding the rights of co-heirs when faced with an improper registration by one heir and subsequent dealings with third parties. It affirmed that co-heirs can assert their inherited shares without prior registration against those claiming under the defective title of another co-heir, and clarified that the appropriate remedy is a partial cancellation or correction of the faulty registration to reflect true ownership.

While the core finding of this 1963 judgment regarding the assertion of statutory inheritance shares without registration against such parties remains consistent with the legislative intent behind the newer Article 899-2 of the Civil Code, the legal landscape for inherited rights exceeding statutory shares has been significantly modified by this recent amendment. The 1963 ruling, therefore, stands as a key historical precedent, parts of which have been reinforced and other related aspects refined by modern legislative efforts to balance the security of inherited rights with the overall safety of property transactions.