Inherited Land in Japan: Using the National Treasury Reversion System

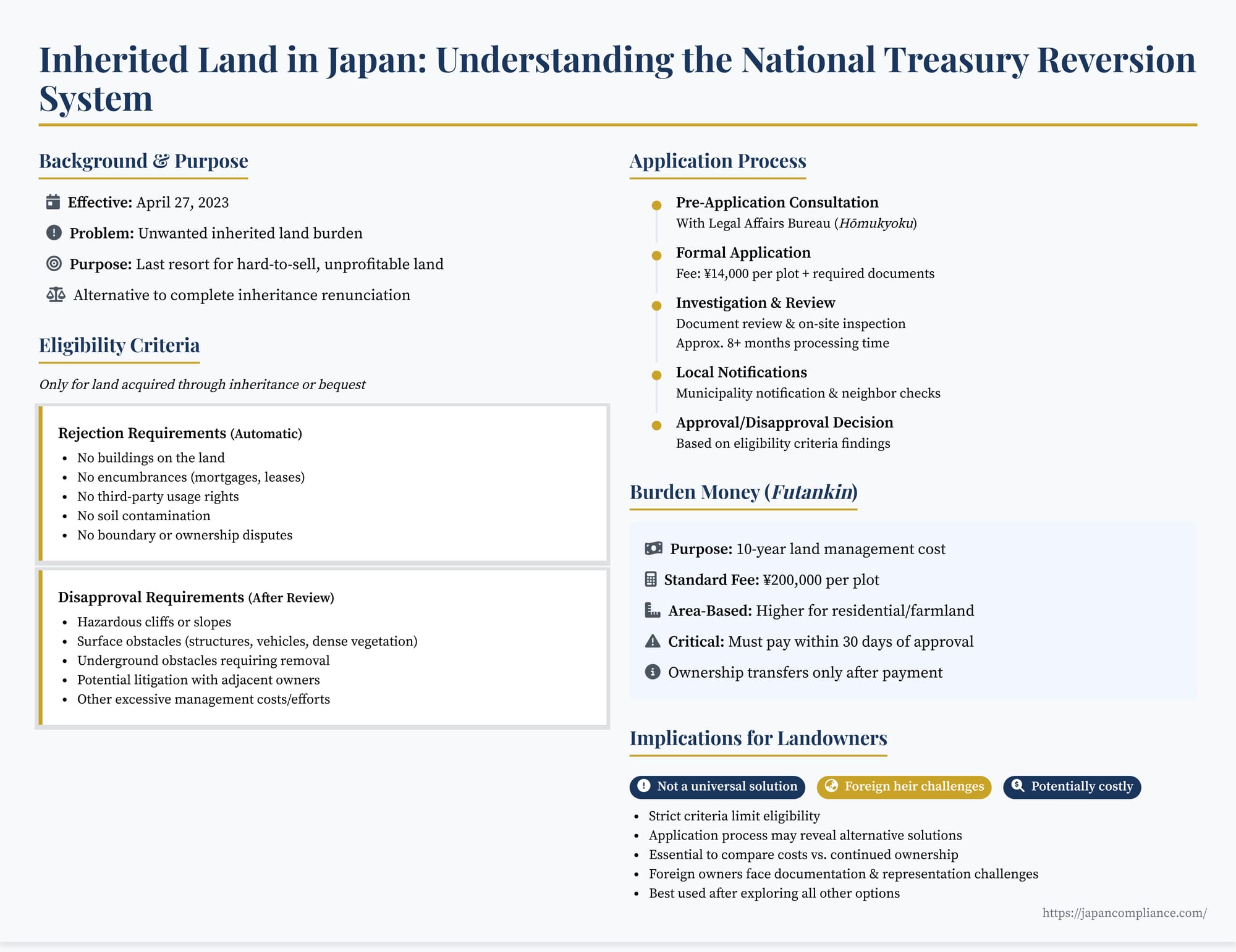

TL;DR: Japan’s National Treasury Reversion System lets heirs dump burdensome inherited land, but only if the parcel is vacant, dispute-free, and the heir pays a hefty “burden money” fee. It is a costly last resort—not a quick fix—for the owner-unknown land crisis.

Table of Contents

- The Dilemma of Unwanted Inherited Land

- What is the National Treasury Reversion System?

- Who is Eligible to Apply?

- What Land Qualifies? The Strict Eligibility Criteria

- The Application and Approval Process

- The Cost: Burden Money

- What Happens to Reverted Land?

- Implications and Considerations

- Conclusion: An Innovative but Demanding Option

The Dilemma of Unwanted Inherited Land

Inheriting property in Japan, particularly land in rural or depopulated areas, can sometimes present more of a burden than a benefit. Heirs, whether residing in Japan or overseas, may find themselves responsible for land that is difficult to manage, costly to maintain (due to property taxes and upkeep), has little to no market value, and cannot easily be sold or even given away. This situation is a significant contributor to Japan's growing problem of "land with unknown owners" (shoyūsha fumei tochi), as heirs may simply abandon the property implicitly by neglecting registration and management.

Traditionally, the primary way to avoid responsibility for unwanted inherited assets was through "inheritance renunciation" (相続放棄 - sōzoku hōki). However, this requires renouncing all inherited assets, including potentially valuable ones like cash or securities, making it an unsuitable option for many.

Recognizing this gap, the Japanese government introduced a novel system as part of its 2021 legal reforms aimed at tackling the ownerless land crisis: the System for Reversion of Land Ownership Acquired by Inheritance, etc., to the National Treasury (相続等により取得した土地所有権の国庫への帰属に関する法律 - Sōzoku tō ni yori shutoku shita tochi shoyūken no kokko e no kizoku ni kansuru hōritsu). This law (Act No. 25 of 2021), which came into effect on April 27, 2023, allows heirs, under stringent conditions, to relinquish ownership of specific unwanted inherited land directly to the Japanese government.

This system offers a potential pathway out for heirs burdened by certain types of land, but it is far from a simple disposal mechanism. It involves a rigorous application process, strict eligibility criteria, and potentially significant costs. Understanding its framework is crucial for anyone, including foreign nationals or entities, dealing with potentially burdensome inherited land in Japan.

What is the National Treasury Reversion System?

The core purpose of this system is to provide a last resort for heirs who have acquired land through inheritance or bequest (not through purchase or other means) and find it impossible or extremely difficult to manage, sell, or donate. By allowing such land to revert to the national treasury, the system aims to prevent it from becoming derelict and ownerless, thereby contributing to the proper management of national land resources.

It is explicitly designed as an alternative to inheritance renunciation, allowing heirs to keep desired assets while divesting only the problematic land parcel(s). However, its strict conditions are intended to prevent moral hazard (owners neglecting land knowing they can revert it) and the unfair transfer of management costs for fundamentally unusable land onto the taxpayer.

Who is Eligible to Apply?

The system is available only to individuals who have acquired ownership (or co-ownership) of the land through inheritance or bequest.

- It cannot be used for land acquired through purchase, original development, or other means during one's lifetime.

- If the land is co-owned by multiple heirs as a result of inheritance, all co-owners must apply jointly. Agreement among all heirs is necessary.

What Land Qualifies? The Strict Eligibility Criteria

This is where the system presents significant hurdles. The Act establishes two layers of screening criteria. Failure to meet the first set results in immediate rejection (kyakka), while failing the second set leads to disapproval (fushōnin) after investigation.

1. Rejection Requirements (申請却下要件 - Shinsei Kyakka Yōken) (Act Art. 2, Para. 3)

An application will be rejected outright if the land falls into any of these categories:

- (a) Buildings Exist: There is any kind of building (house, shed, etc.) on the land. The land must be vacant.

- (b) Encumbrances: Security rights (like mortgages - 抵当権 teitōken) or rights intended for use and profit (like superficies - 地上権 chijōken, leases - 賃借権 chinshakuken, easements for passage - 通行地役権 tsūkō chiekiken) are registered or exist on the land.

- (c) Third-Party Use: The land includes pathways or other areas designated or currently used by third parties (excluding incidental passage).

- (d) Contamination: The land is contaminated by specified hazardous substances under the Soil Contamination Countermeasures Act (e.g., lead, arsenic, specific organic compounds).

- (e) Boundary/Ownership Disputes: The boundaries of the land are unclear, or there is an ongoing dispute regarding the existence, attribution, or scope of ownership rights.

2. Disapproval Requirements (不承認要件 - Fushōnin Yōken) (Act Art. 5, Para. 1)

Even if the land passes the initial rejection check, the Minister of Justice (delegated to the Legal Affairs Bureau) will disapprove the application if the land is deemed to require excessive cost or effort for normal management or disposal. This includes land that:

- (a) Has Hazardous Cliffs: Contains cliffs meeting specific criteria (generally, 30-degree slope and 5m height) where normal management would entail excessive cost or labor.

- (b) Contains Obstacles on Surface: Has structures, derelict vehicles, certain types of vegetation (like dense bamboo thickets requiring special removal), or other physical objects on the surface that impede normal management or disposal.

- (c) Contains Underground Obstacles: Has objects buried underground (e.g., old foundations, waste) that must be removed to allow for normal management or disposal.

- (d) Requires Litigation for Management: Normal management or disposal is impossible without resorting to litigation with owners of adjacent land or other related parties (e.g., access disputes not covered by rejection criteria).

- (e) Otherwise Requires Excessive Cost/Effort: A catch-all category for land that, for other reasons, would impose an undue burden on the state if accepted (e.g., requiring significant ongoing maintenance like specialized slope management not covered by (a), or located in extremely inaccessible areas).

Essentially, the land must be relatively "clean," unencumbered, undisputed, and not pose unusual management difficulties for the state to take it over.

The Application and Approval Process

Applying for land reversion involves several steps:

- Pre-Application Consultation: Prospective applicants are encouraged (though not required) to consult with the Legal Affairs Bureau (法務局 - Hōmukyoku) that has jurisdiction over the land's location. This helps determine likely eligibility and understand the required documentation.

- Formal Application: Submit the application form along with required documents to the competent Legal Affairs Bureau. Documents typically include proof of inheritance, identity verification, land registry information, maps/drawings showing boundaries, photos of the land's condition, and potentially documents related to adjacent land. An application fee (currently ¥14,000 per plot) is required.

- Review and Investigation: The Legal Affairs Bureau reviews the documents for compliance with the rejection criteria. If these are cleared, they conduct further investigations, including on-site inspections, to check for disapproval criteria. This phase involves assessing the land's condition, boundaries, potential obstacles, and management needs. The standard processing time is officially estimated at around 8 months, but complex cases may take longer.

- Notification to Local Entities & Neighbors: During the review, the Legal Affairs Bureau notifies the relevant municipality and other government agencies (like agricultural committees for farmland) about the application. This provides an opportunity for local entities to consider accepting the land as a donation instead. Furthermore, confirming boundaries often involves contacting adjacent landowners. These contacts can sometimes lead to neighbors offering to acquire the land themselves, either through purchase or donation. Statistics indicate that a notable number of applications are withdrawn because such alternative solutions emerge during the process.

- Approval or Disapproval: Based on the investigation, the Legal Affairs Bureau (acting for the Minister of Justice) issues a formal notice of approval or disapproval. Disapproval will state the reasons based on the criteria listed above.

The Cost: Burden Money (負担金 - Futankin)

Approval is not the final step. If the application is approved, the applicant(s) must pay a significant "burden money" (futankin) before ownership transfers to the state (Act Art. 10).

- Basis: This fee represents the estimated standard management costs the government would incur for the land over a 10-year period. It is not based on the land's market value (which is often negligible).

- Calculation:

- The standard amount for many land types (like miscellaneous land - zasshuchi) is a flat ¥200,000 per plot.

- However, for specific categories like urban residential land (takuchi), farmland (ta, hatake), and forests (sanrin), the calculation is based on area, often using formulas defined by ordinance. For example:

- Urban residential land in certain designated areas might have formulas like (Area in m² × ¥X) + ¥Y. Specific examples cited based on early implementation suggest costs can easily reach ¥500,000 to over ¥1,000,000 for moderately sized urban/suburban plots.

- Agricultural land and forests also have area-based calculations, often tiered by size.

- Payment Deadline: The burden money must typically be paid within 30 days of receiving the approval notice.

Crucially, ownership only transfers to the National Treasury upon payment of this burden money. Failure to pay within the deadline invalidates the approval. The substantial cost is a major factor potential applicants must consider.

What Happens to Reverted Land?

Once ownership vests in the National Treasury, the land becomes "ordinary national property" (普通財産 - futsū zaisan). Its management and potential disposal fall under the jurisdiction of:

- The Ministry of Finance (via local Finance Bureaus - 財務局 Zaimukyoku) for most land types like residential land, miscellaneous land, etc.

- The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (MAFF) (via local Agricultural Administration Offices - 地方農政局 Chihō Nōseikyoku or Forestry Bureaus - 森林管理局 Shinrin Kanrikyoku) for farmland and forests, respectively.

How these agencies will manage or dispose of what are often small, scattered, low-value plots remains a significant long-term challenge. While some might eventually be sold or utilized for public purposes, many may require ongoing basic management (e.g., grass cutting, boundary maintenance) funded by taxpayers indefinitely. Finding efficient and beneficial uses for this growing portfolio of reverted land is an area of ongoing policy discussion.

Implications and Considerations

The National Treasury Reversion System is a targeted tool with specific implications:

- Not a Universal Solution: The strict eligibility criteria (especially the "no buildings" rule and hurdles related to management costs/disputes) and the potentially high burden money mean this system is not a viable option for all unwanted inherited land.

- "Last Resort" Principle: It is intended for situations where sale, donation, or other forms of transfer have proven genuinely difficult or impossible. Applicants should explore alternatives first.

- Potential for Facilitating Other Solutions: As noted, the application process itself, through notifications and boundary checks, can sometimes trigger interest from municipalities or neighbors, leading to a resolution before reversion occurs. This "matchmaking" aspect is an interesting secondary effect.

- Complexity for Foreign Heirs: While foreign nationals who inherit Japanese land can use the system, they face the additional hurdles of providing equivalent foreign documentation, potentially needing local representatives, and managing the process (including site visits and payments) from abroad.

- Limited Direct Business Application: The system is designed for individuals who inherited land. Businesses generally cannot use it directly for land they acquired through purchase. However, it might indirectly impact business if it resolves issues with adjacent inherited plots that were hindering development or causing nuisances, though this relies on the heirs choosing to apply and qualifying.

Conclusion: An Innovative but Demanding Option

The Inheritance Land Reversion System is an innovative legal mechanism created to address a specific facet of Japan's ownerless land problem – the burden on heirs inheriting unwanted, unmarketable, and hard-to-manage properties. It provides a formal pathway for relinquishing such land to the state, preventing its potential abandonment.

However, it is crucial to recognize that this is a highly conditional and costly "last resort." The stringent eligibility requirements related to the land's condition, encumbrances, and potential management burdens, combined with the substantial 10-year management fee (burden money), mean that only a subset of unwanted inherited land will qualify and be feasible for reversion. While the system demonstrates the government's effort to provide solutions, potential applicants, including those overseas, must carefully evaluate the criteria, costs, and alternative options before pursuing this demanding process. It reflects the ongoing balancing act between alleviating individual hardship and managing the public cost associated with taking responsibility for the nation's problematic land assets.

- Navigating Japan’s Land-with-Unknown-Owners Crisis: New Laws and Business Implications

- Mandatory Inheritance Registration in Japan: What US Companies & Expatriates Need to Know

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan: Key Differences for U.S. Investors

- Ministry of Justice — Guide to the Land Reversion System

https://www.moj.go.jp/MINJI/minji06_00345.html