Inheritance and Acquisitive Prescription: Can an Heir's Possession Become "Ownership" in Japan?

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of November 12, 1996 (Heisei 8) (Case No. 228 (O) of 1995 (Heisei 7))

Subject Matter: Claim for Land Ownership Transfer Registration Procedures (土地所有権移転登記手続請求事件 - Tochi Shoyūken Iten Tōki Tetsuzuki Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

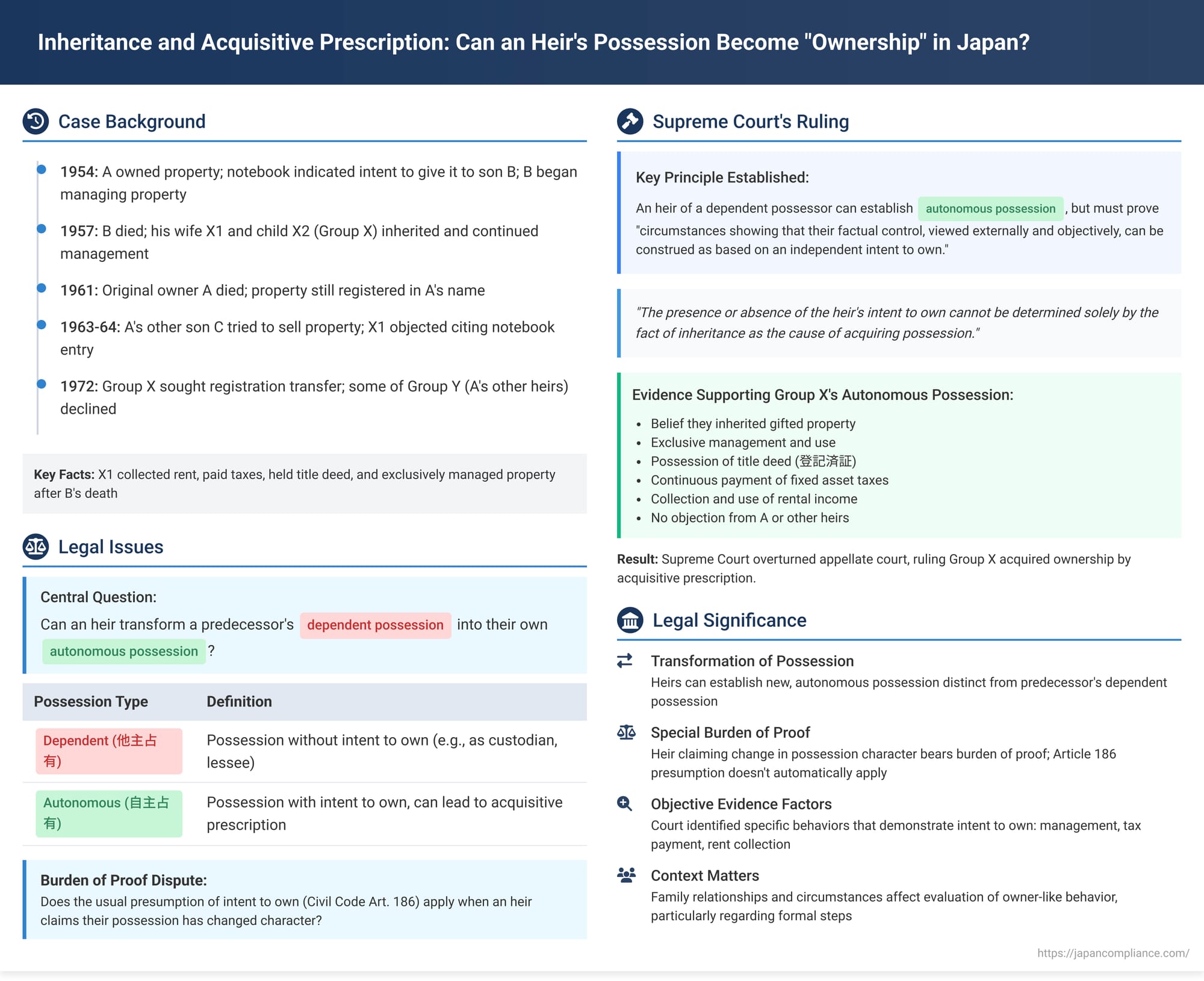

This article explores a 1996 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses a nuanced issue at the intersection of inheritance law and the doctrine of acquisitive prescription (取得時効 - shutoku jikō). Specifically, the case examines how the nature of possession can change upon inheritance, potentially allowing the heir of a person who possessed property without an intent to own (e.g., as a custodian or lessee – known as "dependent possession" or 他主占有 - tashu sen'yū) to subsequently acquire that property by prescription through their own "autonomous possession" (自主占有 - jishu sen'yū) with the intent to own. The Court's decision clarifies the burden of proof and the types of circumstances that can demonstrate this transformation in the character of possession by an heir.

The dispute involved Group X (appellants/plaintiffs), the heirs of B, who claimed ownership of land and buildings by acquisitive prescription, and Group Y (appellees/defendants), the other heirs of the original owner, A.

Factual Background

In 1954, A owned the land and buildings in question (the "Property"), part of which was leased to third parties. A maintained a notebook detailing his numerous real estate holdings, their valuations, and rental income. This notebook contained an entry indicating that the Property was to be given to his fifth son, B. From around May 1954, B began to possess and manage the Property. He dealt with the tenants, collected rent, and used this income for his own living expenses.

B passed away on July 24, 1957. His heirs, his wife X1 and child X2 (collectively Group X), succeeded to his possession of the Property. X1 exclusively managed the Property, continued to negotiate with tenants, collected rent, and used it for their family's living expenses. X1 also held the certificate of completed registration (登記済証 - tōkizumishō, a type of title deed) for the Property and continuously paid the fixed asset taxes on it.

A, the original owner and B's father, died in February 1961. His heirs included his wife Y1, his eldest son C, his second son Y2, his fourth son D, his eldest daughter Y3 (Y1, Y2, Y3 forming part of Group Y), and his grandson X2 (B's child, also an heir of A by representation). Around 1963-1964, C attempted to sell the Property to settle A's debts. However, X1 objected, citing the notebook entry indicating A’s intention to give the Property to B, and the sale did not proceed.

In June 1972, since the Property was still registered in the deceased A's name, X1 requested the cooperation of Group Y (A's other heirs) to complete the ownership transfer registration into the names of X1 and X2. Y1 agreed to this, but Y2 reserved his answer, and Y3, citing lack of knowledge of the circumstances, did not consent. As a result, the registration was not completed.

Group X then filed a lawsuit against Group Y, seeking the ownership transfer registration. Their claims were based on: (1) an alleged gift of the Property from A to B, followed by inheritance by Group X; (2) alternatively, acquisitive prescription based on B's possession, succeeded by Group X; or (3) alternatively, acquisitive prescription based on Group X's own independent possession after B's death.

The first instance court found that there was a gift from A to B and ruled in favor of Group X. However, the appellate court overturned this, dismissing Group X's claims. The appellate court found no conclusive evidence of a completed gift from A to B. It determined that B's possession was based on a mandate (委任契約 - inin keiyaku) from A to manage the property, and thus was "dependent possession" (tashu sen'yū) without intent to own. The appellate court further held that this dependent character of possession did not change to autonomous possession (jishu sen'yū) for Group X upon inheriting B's possession. It cited X1's lack of specific action regarding an inheritance tax return for A's estate filed around 1963 (which listed the Property as part of A's estate) and the fact that Group X only sought ownership registration in 1972 as reasons for this finding. Group X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court overturned the appellate court's decision and, in a rare move of "self-judgment" (破棄自判 - haki jihan), ruled in favor of Group X, ordering the registration transfer.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- General Presumption vs. Heir of Dependent Possessor:

The Court first acknowledged the general rule under Article 186, paragraph 1 of the Civil Code: a possessor is presumed to possess with the intent to own (autonomous possession). Therefore, a party contesting acquisitive prescription by arguing that the possession was merely dependent normally bears the burden of proving that the possession was based on a title that by its nature lacks intent to own (e.g., lease, mandate) or that the possessor, by their objective conduct, did not intend to oust the true owner's rights. The Court referenced its prior rulings that mere failure to seek registration or pay property taxes does not, by itself, definitively negate the intent to own, as these can be influenced by personal relationships or other circumstances. - Burden of Proof on Heir Claiming Change in Nature of Possession:

However, the Court then laid down a crucial distinction for when an heir of a dependent possessor asserts acquisitive prescription based on their own, new period of possession (as opposed to merely tacking on the predecessor's possession):

"When an heir of a dependent possessor asserts the completion of acquisitive prescription based on their own possession, for that possession to be considered as based on an intent to own, it is appropriate that the heir, as the possessor, must themselves prove circumstances showing that their factual control, when viewed externally and objectively, can be construed as being based on an independent intent to own. This is because the prior nature of possession has been altered by the heir commencing a new factual control, and thus the party asserting acquisitive prescription should prove this change. Furthermore, in such cases, the presence or absence of the heir's intent to own cannot be determined solely by the fact of inheritance as the cause of acquiring possession."

This means the usual presumption of intent to own under Article 186(1) does not directly apply to an heir of a dependent possessor who claims their own possession has become autonomous; they must affirmatively show it. - Application to the Facts – Group X's Autonomous Possession:

Applying this to the present case, the Supreme Court found that Group X had established that their possession, after B's death, was based on an independent intent to own:- X1, after B's death, believed that B had received the Property as a gift from A and that she and X2 had inherited it.

- Based on this belief, X1 exclusively managed and used the Property, held the title deed (登記済証 - tōkizumishō), and continuously paid the fixed asset taxes.

- X1 collected rents from tenants and used this money exclusively for Group X's living expenses.

- The Property had traditionally been managed as a single unit among A's properties in that city.

- The Court concluded that Group X, upon B's death, not only succeeded to B's possession by inheritance but also newly commenced factual control over the entire Property, thereby initiating their own possession.

- Lack of Objection and Subsequent Conduct of Other Heirs:

Critically, A and his other legal heirs (Group Y) were aware of the manner in which Group X was factually controlling the Property. Yet, there was no evidence that they raised any objection to Group X's possession. Moreover, when X1 sought cooperation for registration in 1972, Y1 (A's wife) acknowledged the gift to B/X1, and Y2 (A's son) and Y3 (A's daughter) did not initially object strongly. - Conclusion on Intent to Own:

Given these circumstances, the Supreme Court held that Group X's factual control over the Property, viewed externally and objectively, was indeed based on an independent intent to own. The appellate court's reasons for denying this (X1's inaction on the inheritance tax return and the timing of the registration request) were deemed insufficient to negate this intent, especially considering the family relationships involved, which might explain non-confrontational behavior. Such conduct was not necessarily "abnormal" for an owner in that context.

Therefore, since Group X's possession was found to be autonomous, and Group Y had not proven any interruption of the prescription period, Group X was deemed to have acquired ownership of the Property by acquisitive prescription 20 years after they commenced their own possession on July 24, 1957 (the date of B's death). The Supreme Court itself then issued the judgment ordering the transfer of registration to Group X.

Justice Kabe's Supplementary Opinion

Justice Kabe provided a supplementary opinion, reviewing the evolution of case law on determining "intent to own" for acquisitive prescription, particularly following a significant 1983 Supreme Court decision. He emphasized that while Article 186(1) presumes intent to own, this can be rebutted by showing the possession originated from a title that by nature lacks such intent (e.g., lease) or by circumstances objectively indicating the possessor did not intend to exclude the true owner's rights. He noted that the 1983 case highlighted factors like "not taking actions a true owner normally would" or "acting in a way a true owner normally wouldn't" as grounds to rebut the presumption. However, Justice Kabe also pointed to a subsequent 1995 Supreme Court decision (cited by the majority here) which cautioned against over-relying on factors like failure to seek registration or pay taxes as definitive proof of lacking intent to own, as family dynamics or other circumstances could explain such omissions. He viewed the current majority opinion as consistent with this more nuanced approach, correctly evaluating the specific family context in finding that Group X's actions (or inactions regarding certain formal steps) did not negate their objectively demonstrated intent to possess as owners.

Analysis and Implications

This 1996 Supreme Court judgment is a significant clarification of how acquisitive prescription applies to heirs, particularly when the predecessor's possession was dependent (tashu sen'yū).

- Heir Can Establish Own Autonomous Possession: The case firmly establishes that an heir of a dependent possessor is not necessarily locked into the dependent nature of that prior possession. The heir can, through their own actions and circumstances following the inheritance, establish a new, independent possession that is autonomous (jishu sen'yū) and can thus form the basis for their own claim of acquisitive prescription.

- Burden of Proof Shifts for "New" Autonomous Possession by Heir: Crucially, when an heir of a dependent possessor claims that their own subsequent possession became autonomous, the usual presumption of intent to own (Article 186(1)) does not automatically apply to prove this change in character. The heir themselves bears the burden of demonstrating, through objective, external facts, that their new factual control over the property is indeed based on an independent intent to own. This differs from a scenario where someone initially starts possessing property without a prior dependent possessor in their chain.

- Factors Demonstrating Independent Intent to Own: The Court looked at a combination of factors to determine Group X's independent intent:

- Belief of Ownership: Their belief (derived from A's notebook and B's statements) that they were the rightful owners by gift and inheritance.

- Exclusive Management and Use: Actively managing the property, dealing with tenants, collecting and using rent for their own sustenance.

- Possession of Title Deed: Holding the certificate of completed registration.

- Payment of Taxes: Continuously paying fixed asset taxes.

- Lack of Objection by True Owner's Heirs: The acquiescence or lack of challenge by A's other heirs for a significant period.

- Affirmative Actions: X1's later attempt to secure registration, and Y1's (A's wife's) acknowledgment.

- Context Matters (Especially Family Relationships): The Court emphasized that actions or inactions (like not immediately demanding registration or contesting a tax return) must be viewed in their full context, including interpersonal family relationships. What might seem like a lack of owner-like behavior in a commercial setting might be perfectly understandable and not indicative of a lack of intent to own within a family context.

- "New Factual Control": The concept that the heir must "newly commence factual control" is important. It's not just a passive continuation of the predecessor's possession; it implies the heir establishing their own direct and independent dominion over the property in a manner consistent with ownership.

This judgment provides a nuanced framework for assessing claims of acquisitive prescription by heirs of dependent possessors. It balances the need for the heir to demonstrate a clear shift to autonomous possession against the understanding that family contexts can influence how "owner-like" behavior is manifested, particularly regarding legal formalities like registration. It underscores that an objective assessment of all circumstances surrounding the heir's possession is critical.