Individual Income Attribution and Spousal Contributions: A 1961 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Case: Supreme Court Grand Bench Judgment, September 6, 1961 (Showa 34 (O) No. 1193: Action for Rescission of Income Tax Assessment Review Decision)

Introduction

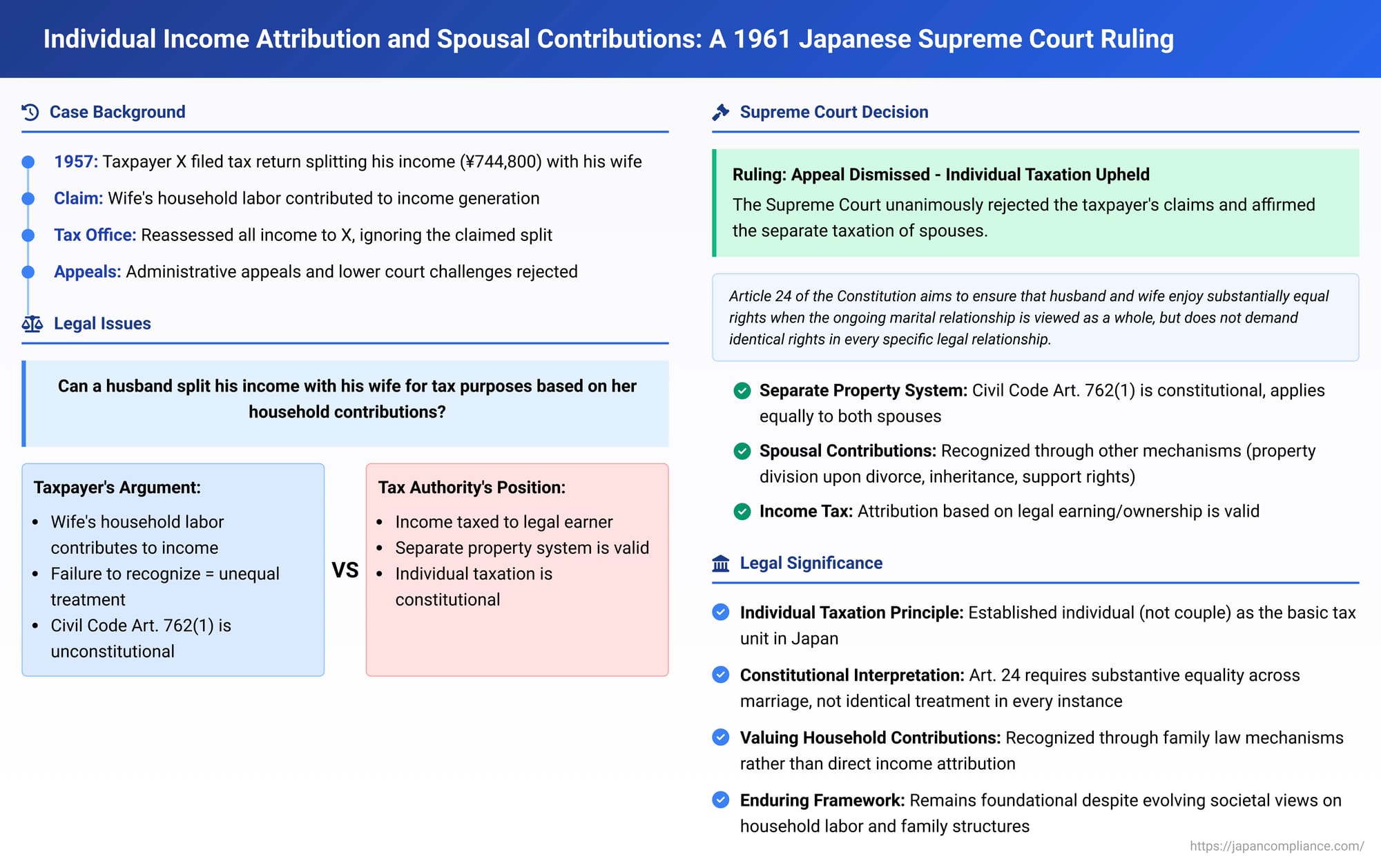

On September 6, 1961, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark decision addressing fundamental questions about the unit of taxation for individuals and the recognition of a spouse's non-economic contributions within the income tax framework. The case revolved around a taxpayer's attempt to split his declared income with his wife for tax purposes, arguing that her household labor contributed significantly to his earnings. This challenge brought into focus the interplay between Japan's Income Tax Act, the Civil Code's provisions on marital property, and the constitutional principles of equality and individual dignity in marriage. The Court's ruling clarified the prevailing principle of individual taxation in Japan and the constitutional validity of the system of separate property for married couples as a basis for income attribution.

The core issue was whether income legally earned and registered in the name of one spouse (the husband, X) could be divided and partly attributed to the other spouse (his wife) for income tax calculation, based on her contributions through household labor and general support. The taxpayer contended that failing to recognize such contributions for tax purposes violated the constitutional guarantee of equality between the sexes. The tax authority, Y, maintained that income should be taxed to the individual in whose name it was earned, in line with existing legal frameworks.

Facts of the Case

The appellant, X, when filing his income tax return for the year 1957, declared a total income that included employment income of 165,600 yen and business income of 459,200 yen. X asserted that these amounts were obtained through the cooperation of his wife, particularly her contributions through household labor and other forms of support. Based on this premise, he argued that these portions of his income should be considered as belonging equally to both himself and his wife. Consequently, X calculated his taxable income by taking one-half of the combined employment and business income, adding to it the full amount of his dividend income (119,800 yen), resulting in a declared total income of 432,200 yen.

The director of the competent tax office disagreed with X's approach. The tax office issued a corrective reassessment, attributing all the aforementioned income (employment, business, and dividend) solely to X. This resulted in an increased tax liability for X, and an underpayment penalty was also imposed on the additionally assessed amount.

X, being dissatisfied with this reassessment, filed an objection and subsequently a request for an administrative review with the Osaka Regional Taxation Bureau Chief, Y (the appellee). However, his appeals were dismissed. X then initiated legal proceedings seeking the cancellation of these administrative decisions. The court of first instance, the Osaka District Court (judgment of January 17, 1959), dismissed X's claim. His appeal to the Osaka High Court (judgment of September 3, 1959) was also dismissed.

X further appealed to the Supreme Court. His central argument on final appeal was that the tax authority's determination, by failing to evaluate his wife's contributions to the household and their joint life, undermined her dignity and violated the principle of the essential equality of the sexes, as enshrined in Article 24 of the Constitution of Japan. He contended that Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, which stipulates the system of separate marital property and formed the basis for the tax authority's decision, was unconstitutional. Consequently, he argued, the Income Tax Act, by relying on this allegedly unconstitutional provision of the Civil Code, was itself unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, sitting as a Grand Bench, unanimously dismissed X’s appeal, thereby upholding the decisions of the lower courts and the tax authority. The Court's reasoning systematically addressed the constitutional challenge, focusing on the interpretation of Article 24 of the Constitution, the validity of Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, and the consequential constitutionality of the Income Tax Act.

Interpretation of Article 24 of the Constitution

The Court began by interpreting Article 24 of the Constitution. This article states: "Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis" (Paragraph 1) and "With regard to choice of spouse, property rights, inheritance, choice of domicile, divorce and other matters pertaining to marriage and the family, laws shall be enacted from the standpoint of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes" (Paragraph 2).

The Supreme Court expounded on the meaning of these provisions:

- Article 24 lays down the principles of individual dignity and the essential equality of the sexes, which are fundamental tenets of democracy, specifically in the context of marriage and family relations.

- It signifies that men and women are essentially equal, and therefore, it prohibits unequal treatment between a husband and a wife merely on account of their status as husband or wife.

- The overarching aim of Article 24 is to ensure that, when the ongoing marital relationship is viewed as a whole, the husband and wife will enjoy substantially equal rights.

- However, the Court clarified that Article 24 does not go so far as to demand that husband and wife must invariably possess identical rights in every specific, concrete legal relationship. The constitutional expectation is for substantive equality in the broader context of the marital partnership, not necessarily formal identity of rights in all individual legal provisions.

Constitutionality of Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code

Next, the Court examined Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. This provision states: "Property owned by one party before marriage and property acquired in that party's own name during marriage shall be his or her separate property (referred to as 'separate property')."

The Court found this provision to be constitutional for the following reasons:

- The rule of separate property, as defined in Article 762, Paragraph 1, applies equally to both husband and wife. It does not inherently discriminate based on gender.

- The Court acknowledged the appellant's argument that spouses form a cooperative unit and that one spouse often contributes to the other's acquisition of property. However, it pointed out that the Civil Code contains other provisions designed to address and compensate for such mutual cooperation and contribution. These include:

- The right to claim distribution of property upon divorce (財産分与請求権, zaisan bun'yo seikyūken).

- Inheritance rights (相続権, sōzokuken).

- The right to claim support or maintenance (扶養請求権, fuyō seikyūken).

- The Court viewed these related rights as legislative measures intended to ensure that no substantive inequality arises between spouses as a result of their mutual cooperation and contributions throughout the marriage. By exercising these rights, a spouse's contributions can be recognized and compensated, leading to an outcome of substantive equality in the long run.

- Therefore, the Court concluded that Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, when considered in light of the overall intent of Article 24 of the Constitution as previously interpreted, is not unconstitutional.

Constitutionality of the Income Tax Act

Having established the constitutionality of Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code, the Court then turned to the Income Tax Act itself.

- The Court noted that the Income Tax Act, as applied in this case for calculating the income of spouses living together, relies on the principle of separate property (いわゆる別産主義, iwayuru bessanshugi) established by Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code. This means that income is generally attributed to the spouse in whose name it is earned or to whom the income-generating property legally belongs.

- Since Article 762, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Code was found not to violate Article 24 of the Constitution, the Court reasoned that the Income Tax Act, by basing its income attribution rules on this constitutional provision of the Civil Code, also cannot be deemed unconstitutional.

Thus, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower court's judgment, finding no grounds to support the appellant's claims of unconstitutionality. The appeal was dismissed, and the litigation costs were to be borne by the appellant, X.

Commentary Insights and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 1961 decision has had lasting significance in shaping the understanding of individual taxation and marital property rights in Japan.

Significance of the Ruling and the Separate Property System

This judgment firmly upheld the constitutionality of Japan's system of separate marital property, as defined in Civil Code Article 762, Paragraph 1, against challenges based on Article 24 of the Constitution. Consequently, it also validated the Income Tax Act's reliance on this system for determining individual tax liability.

The separate property system is recognized for granting spouses economic independence. However, a criticism often leveled against it is that it may not adequately value or recognize non-market contributions, such as household labor, in the ongoing economic life of the marriage, potentially creating a disparity in substantive equality between spouses, particularly for the spouse primarily engaged in such labor.

The Supreme Court, in this decision, interpreted Article 24 of the Constitution as aiming for "substantially equal rights" for husband and wife when viewed holistically, rather than mandating "identical rights in every specific instance". While acknowledging spousal cooperation, the Court found that the Civil Code addresses this through mechanisms like property division upon divorce, inheritance, and support rights. Even if these mechanisms, particularly property division which often occurs at the dissolution of marriage, represent a somewhat "negative format" for settling accounts on spousal contributions, the Court did not see this approach as inherently violating the constitutional principle of the essential equality of the sexes.

Tax Unit and the "Calculation of a Couple's Income"

The concept of the "tax unit" (課税単位, kazei tan'i) is central to this case. A tax unit determines how income is aggregated or divided for the purpose of applying tax rates. Broadly, tax systems can adopt:

- Individual unit taxation: Each individual is taxed separately on their own income.

- Couple unit taxation: The income of both spouses is combined. This can take forms such as "joint filing" where the combined income is taxed as a single sum (aggregate non-division), or "income splitting" where the combined income is notionally divided (e.g., halved, as with a "split-income" or "quotient" system like the deux parts or "two-shares" system) and then subjected to tax, often to mitigate progressive tax rates.

- Family unit taxation: Income of all family members is aggregated, potentially with further divisions based on the number of family members (e.g., an "n-share" or n分n乗 system).

Japan, since the abolition of a family aggregate taxation system in 1950, has adopted the principle of individual unit taxation (個人単位主義, kojin tan'i shugi) for its national income tax. Under this system, each spouse is taxed separately on the income they individually earn or that is legally attributed to them. X's claim was, in effect, an argument for a form of income splitting for a portion of his income, based on his wife's contributions.

The Supreme Court's decision in this case primarily assessed the constitutionality of the Income Tax Act by examining the constitutionality of the underlying Civil Code provision (Article 762, Paragraph 1). However, some legal commentary suggests that the reasoning for the constitutionality of a marital property system under private law (which balances various rights and interests between spouses) might not be identical to the reasoning required for the constitutionality of a tax system. Tax systems are primarily concerned with the fair distribution of the tax burden and principles of tax equity. Issues such as income splitting, the tax neutrality of marriage (i.e., whether marriage itself changes a couple's total tax burden compared to when they were single), and how to value or recognize non-market contributions like household labor for tax purposes involve complex questions of horizontal equity between different households (e.g., single-earner vs. dual-earner couples, couples with vs. without imputed income from household production). Therefore, it has been argued that demonstrating the constitutionality of tax laws should ideally involve considerations specific to tax policy, legislative intent within the tax sphere, and coherence with other tax provisions, such as gift tax rules (which might be implicated if income is freely shifted between spouses without recognition of an underlying legal right to that income).

Enduring Principles and Modern Context

While this judgment was delivered in 1961, the principles it enunciated regarding individual taxation and the legal attribution of income based on separate property remain fundamental aspects of the Japanese income tax system. The Court's deference to the legislative framework, which provides for spousal contributions to be recognized through specific family law mechanisms rather than direct income attribution for tax purposes, established a clear precedent.

The "Considerations for Discussion" section in the provided commentary asks how Article 24 of the Constitution might be interpreted in tax law today, given the diversification of how married couples work and structure their lives. This is an ongoing question. While the 1961 ruling is foundational, societal changes, evolving views on the economic value of household labor, and shifts in family dynamics continually prompt re-evaluation of whether existing legal frameworks achieve substantive equality in practice. However, any significant departure from the principle of individual taxation based on legal ownership or earning, towards a system that more directly accounts for non-market spousal contributions in the annual income tax calculation, would likely require substantial legislative reform rather than solely evolving judicial interpretation, given the clarity of this Supreme Court precedent.

Conclusion

The 1961 Supreme Court decision in the case of X firmly established that, under Japanese law, income is to be taxed to the individual who legally earns it or in whose name income-generating assets are held, consistent with the Civil Code's system of separate marital property. The Court found this system, and the Income Tax Act's reliance upon it, to be constitutional, holding that Article 24 of the Constitution's guarantee of individual dignity and essential equality of the sexes does not mandate income splitting or direct attribution of one spouse's income to the other based on household contributions. Instead, the Court pointed to other legal mechanisms within family law, such as property division upon divorce, inheritance, and support rights, as the legislative means for ensuring substantive equality and recognizing mutual contributions within a marriage over its entire course. This ruling underscores the principle of individual unit taxation in Japan and highlights the distinct legal pathways for the recognition of spousal contributions in private law versus tax law.