Individual Bondholder vs. Corporate Issuer: A 1928 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Independent Redemption Claims

Judgment Date: November 28, 1928

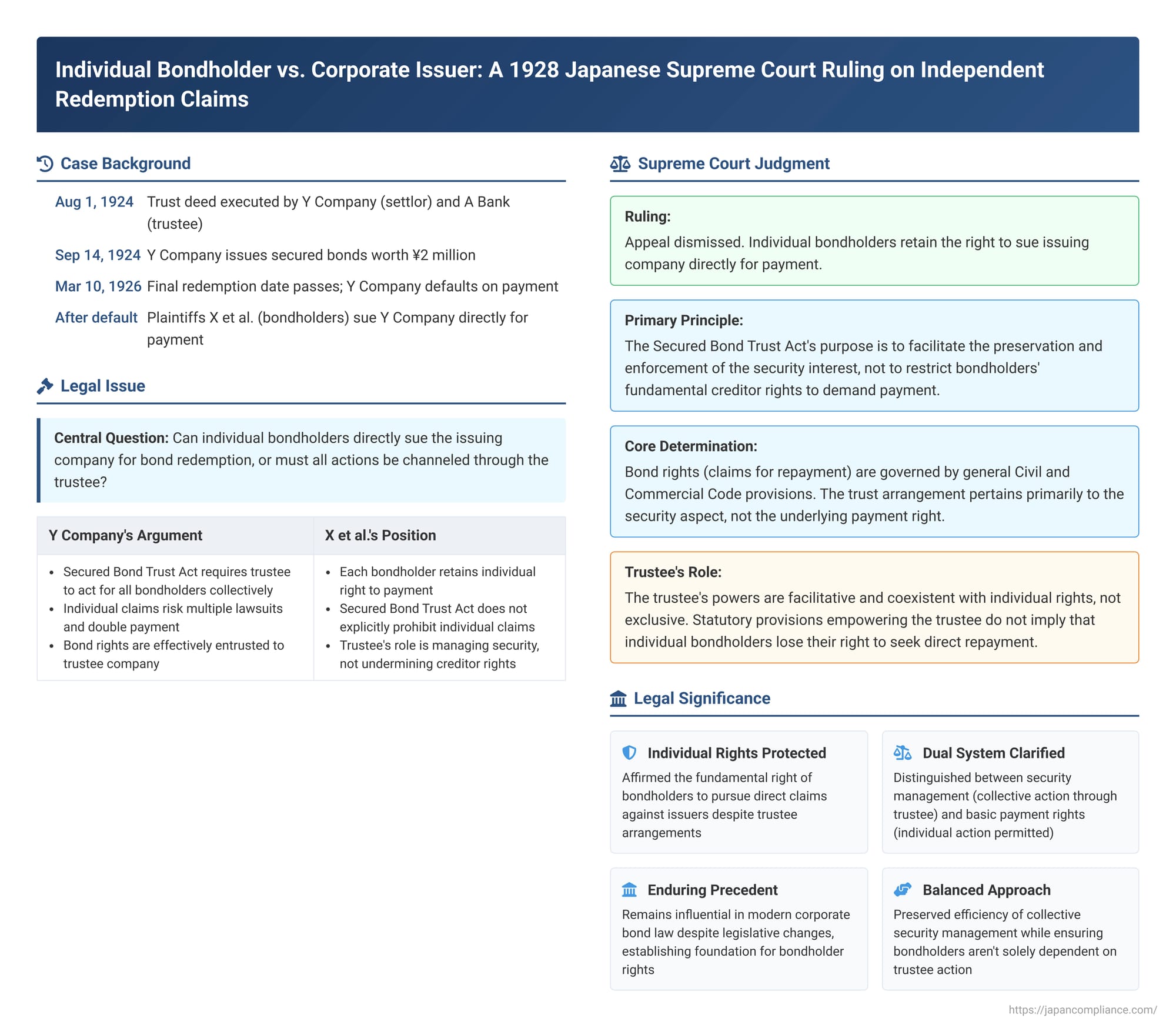

When a company issues bonds, especially those secured by assets, a trustee company is often appointed to manage the security and act in the collective interest of the bondholders. This raises a fundamental question: if the issuing company defaults, can an individual bondholder take direct legal action to recover their investment, or must all such actions be channeled through the trustee? A landmark decision by the Daishin-in, Japan's Supreme Court prior to the current constitution, on November 28, 1928, provided a clear answer to this, establishing a vital principle for bondholder rights that continues to resonate in modern Japanese corporate law.

The Factual Scenario: A Default and Determined Bondholders

The case involved Y Company, which had issued secured bonds on September 14, 1924, with a total value of ¥2 million. This issuance was based on a trust deed dated August 1, 1924, wherein Y Company was the settlor (委託者 - itaku sha) and A Bank was appointed as the trustee company (受託者 - jutaku sha) to hold and manage the security for these bonds.

The plaintiffs, X and another individual (referred to as X et al.), were holders of these secured bonds, each possessing three ¥1,000 bonds. Y Company subsequently defaulted on its obligations, failing to pay the principal and interest due after the final redemption date of March 10, 1926.

In response to this default, X et al. took direct legal action against Y Company, demanding payment of the bond principal, accrued interest, and damages for non-payment.

Y Company's primary defense was rooted in the provisions of the Secured Bond Trust Act (担保附社債信託法 - Tanpo tsuki Shasai Shintaku Hō, the title of which was later slightly amended). Y Company argued that under this Act, secured bondholders were not permitted to independently exercise their rights to claim repayment of the bonds. Instead, such actions, they contended, had to be pursued by the trustee company, A Bank, acting on behalf of all bondholders. Y Company raised concerns about the potential for a multitude of lawsuits from individual bondholders and the risk of double payment if individual claims were allowed.

The lower courts, including the appellate court, generally found in favor of X et al. The appellate court specifically held that the Secured Bond Trust Act contained no provisions that restricted or prohibited individual secured bondholders from independently exercising their bond rights. It therefore rejected Y Company's defense and upheld X et al.'s claim for the most part (some claims for damages were adjusted, and it was noted that Y Company had made partial payments before the appellate judgment).

Y Company appealed to the Daishin-in, reiterating its arguments that:

- The trustee company (A Bank) possessed the legal authority under the Act (specifically citing then-Article 84) to undertake all necessary actions to obtain payment of the bonds.

- The bond rights themselves were effectively entrusted to the trustee company.

- Permitting individual bondholders to sue independently could lead to a chaotic flood of litigation and create scenarios of double recovery or payment.

The Daishin-in's Landmark Ruling

The Daishin-in, in its judgment of November 28, 1928, dismissed Y Company's appeal, thereby affirming the right of individual secured bondholders to sue the issuing company directly for repayment. The Court's reasoning was meticulous:

- Primary Purpose of the Secured Bond Trust Act: The Daishin-in began by clarifying the principal objective of the Secured Bond Trust Act. It stated that the Act's main purpose is to facilitate and ensure the issuance and redemption of bonds by providing a framework for the preservation and enforcement of the security interest (物上担保権 - butsujō tanpoken) that backs the bonds, all based on the underlying trust agreement. The Court noted that the Act itself largely lacks substantive provisions concerning the nature of the bond right (shasaiken - 社債権) as a claim for payment.

- Bond Right Governed by General Laws: Consequently, the bond right itself – the claim for repayment of principal and interest – is primarily governed by the general provisions of the Civil Code and the Commercial Code. These laws define the fundamental creditor-debtor relationship.

- No General Restriction on Bondholders' Rights (Except for Security-Related Matters): Secured bondholders, as creditors, are not restricted in exercising their rights to claim payment, except for matters specifically concerning the administration or enforcement of the security. The Court emphasized that an individual bondholder is entitled to demand redemption from the debtor issuing company.

- Trust Pertains to Security, Not the Core Payment Right: The Daishin-in acknowledged that secured bonds are issued based on a trust agreement between the issuing company and the trustee company, and that the bondholders who acquire these bonds are undoubtedly beneficiaries of this trust. The trustee company has a duty to hold and enforce the security for the benefit of all bondholders, and actions concerning the preservation or enforcement of this collective security generally require collective action or action by the trustee. However, the Court stressed that this framework pertains to the security aspect. It does not act as a barrier to an individual bondholder seeking simple repayment of their matured bond claim without resorting to the enforcement of the security itself.

- Trustee's Powers are Facilitative and Coexistent, Not Exclusive: The Secured Bond Trust Act indeed grants various powers to the trustee company. For example:However, the Daishin-in interpreted these statutory powers as ancillary to the trustee's status, granted for convenience, allowing the trustee to act on behalf of the issuing company or the bondholders. These provisions do not imply that individual bondholders are stripped of their inherent right to act independently to recover their own due debt, nor do they impose a requirement for collective action through the trustee for all purposes, especially for straightforward repayment claims. The Court explicitly rejected the notion that these provisions were intended to prohibit individual bondholders from initiating litigation for repayment.

- Under special mandate in the trust agreement, the trustee can handle all procedures for bond issuance and also undertake all acts concerning redemption and interest payments (then-Article 23 of the Act).

- Unless prohibited by the trust agreement, the trustee can collect the debt on behalf of all bondholders (then-Article 84).

- Following a resolution at a bondholders' meeting, the trustee can undertake litigation, participate in bankruptcy proceedings, grant a moratorium on payments for all bonds, release the issuer from liability for default, or enter into settlements (then-Articles 85 and 86).

Thus, the Daishin-in concluded that Y Company's arguments were unfounded and that X et al. were entitled to pursue their claims directly.

Enduring Relevance in Modern Japanese Corporate Law

This 1928 Daishin-in decision, though delivered under older legislation, remains a cornerstone in understanding bondholder rights in Japan. Its principles are considered broadly applicable to the current Secured Bond Trust Act (last significantly amended in 2005) and, by analogy, to the legal framework governing unsecured bonds where a bond administrator (shasai kanrisha - 社債管理者) is appointed under the Companies Act.

Legal scholarship generally supports the Daishin-in's conclusion and its continued relevance. The rationale is that the fundamental right to claim payment for a due debt belongs to each individual bondholder. Statutory provisions empowering a trustee or bond administrator are typically seen as facilitative or for managing collective interests (especially concerning security or modifications to bond terms), not as divesting individual bondholders of their primary claim for repayment. Indeed, other legal provisions, such as those allowing a trustee to challenge preferential payments made by the issuer to certain bondholders, seem to presuppose that individual bondholders can and do receive payments directly.

The Debate: Individual Claims vs. Collective Action

Despite the Daishin-in's clear stance, the tension between individual bondholder rights and the mechanisms for collective action continues to be a subject of legal discussion.

Arguments for Allowing Independent Bondholder Claims:

- Ownership of the Right: The core debt obligation is owed to each bondholder individually.

- Risk of Trustee/Administrator Inaction: A trustee or bond administrator might not always act promptly or effectively to protect bondholder interests, potentially due to negligence or conflict of interest. Allowing individual claims provides a safeguard.

- Bondholder Autonomy: If a bondholder is willing and able to pursue their own claim, especially for a simple monetary default, restricting this exercise of a fundamental creditor right might be seen as overly paternalistic, particularly if the primary rationale for a trustee/administrator is the impracticality of requiring every bondholder to manage their own complex security interests or participate in collective negotiations.

Arguments for Channeling Claims Through a Trustee/Administrator:

- Preventing a "Race to the Courthouse" and Ensuring Equity: Allowing numerous individual lawsuits could lead to a chaotic situation where some bondholders recover fully while others, perhaps slower to act or with smaller claims, get nothing if the issuer's assets are limited. A trustee or administrator can, in theory, ensure a more orderly and equitable distribution.

- Counterpoint: In situations of genuine insolvency where equitable distribution is paramount, formal bankruptcy or corporate reorganization proceedings are generally considered the appropriate legal mechanisms, overriding individual collection efforts.

- Avoiding Duplicative Litigation and Issuer Burden: Facing multiple lawsuits on the same underlying default can be burdensome for the issuing company.

- Counterpoint: The issuer only has to pay the debt once. Procedural rules in civil litigation can often manage overlapping claims. However, questions can arise if defenses (like set-off) available against one bondholder are also applicable if the trustee sues for the collective.

- Protecting the Collective Interest: Individual actions could sometimes prejudice the interests of the bondholder group as a whole (e.g., a premature enforcement action that diminishes the value of shared security). A trustee or administrator is positioned to consider the broader implications.

When Individual Action Becomes Particularly Crucial

The right of an individual bondholder to pursue their claim becomes especially important in scenarios where the issuing company defaults on its payment obligations as stipulated in the bond terms (e.g., method of redemption under Companies Act Art. 676, Item 4), and the appointed trustee or bond administrator fails to take appropriate or timely action. In such cases, denying individual bondholders the right to sue would effectively mean they bear not only the credit risk of the issuer but also the risk associated with the potential non-performance or inadequate performance of the trustee/administrator.

Limitations on Individual Bondholder Rights Remain

It is important to note that the right of individual bondholders to act independently is not absolute. Japanese law does impose restrictions in certain specific contexts:

- Creditor Objection Procedures: In corporate reorganizations like mergers or demergers, individual bondholders typically cannot independently file objections to protect their claims; this is usually handled collectively through a bondholders' meeting resolution or by the bond administrator (Companies Act Art. 740, Paragraphs 1 and 2).

- Formal Insolvency Proceedings: In corporate reorganization (会社更生 - kaisha kōsei) or civil rehabilitation (民事再生 - minji saisei) proceedings, the bond trustee or administrator usually files a single proof of claim on behalf of all bondholders. Individual bondholders might then be restricted in their ability to exercise voting rights independently unless they follow specific procedures to opt-out or act separately (see Corporate Reorganization Act Art. 190(1); Civil Rehabilitation Act Art. 169-2(1)).

- Collective Decisions: Bondholders' rights can be collectively modified or restricted by resolutions passed at a bondholders' meeting concerning matters such as deferral of payments, waiver of principal or interest, or overall settlement terms (Companies Act Art. 706, Paragraph 1, Item 1). Certain litigation or actions related to insolvency proceedings can also be exclusively entrusted to the bond administrator by a bondholders' meeting resolution or by the terms of the bond issuance itself (Companies Act Art. 706, Paragraph 1, Item 2 and proviso; Art. 676, Item 8).

The possibility of imposing further restrictions on individual bondholder rights beyond these statutory limits, perhaps through the terms of the bond issuance or by bondholder meeting resolutions, is a complex legal question, raising issues about adequate disclosure and the balance between collective efficiency and individual creditor rights.

Conclusion

The Daishin-in's 1928 judgment robustly affirmed the principle that individual holders of secured bonds generally retain the right to sue the issuing company directly for the repayment of their matured claims. While the role of trustee companies (and modern bond administrators) is indispensable for managing shared security, facilitating collective action, and representing bondholders in complex negotiations or reorganizations, this role does not, as a default rule, extinguish the fundamental creditor-debtor relationship that entitles each bondholder to seek payment of what is owed to them. This historic decision continues to safeguard the direct recourse of bondholders, ensuring they are not solely reliant on an intermediary when their primary claim for payment goes unfulfilled.