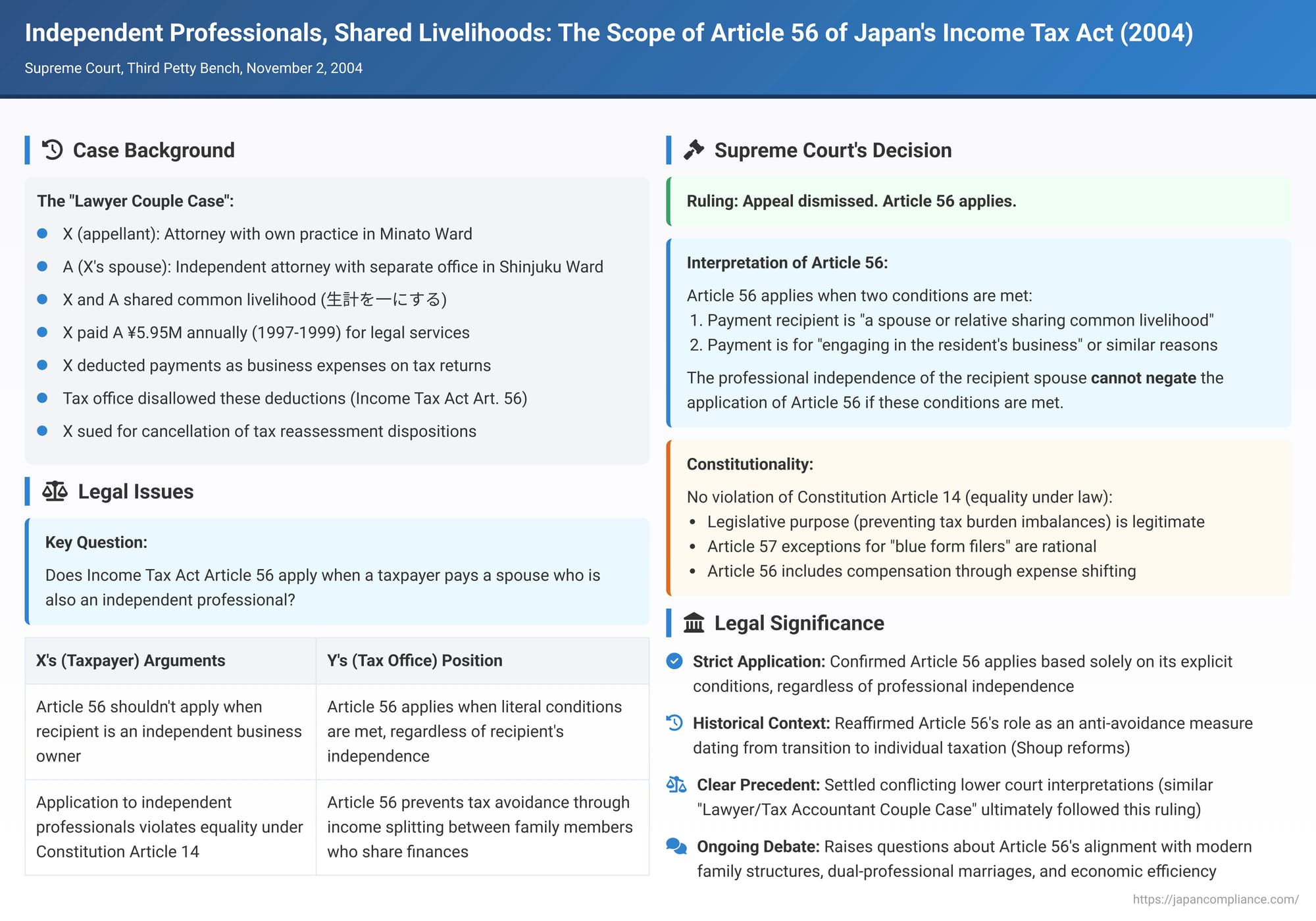

Independent Professionals, Shared Livelihoods: The Scope of Article 56 of Japan's Income Tax Act – The "Lawyer Couple Case"

Case: Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of November 2, 2004 (Heisei 16 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 23: Action for Rescission of Income Tax Reassessment Disposition, etc.)

Introduction

On November 2, 2004, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pivotal judgment in a case commonly referred to as the "Lawyer Couple Case." This decision addressed the scope of Article 56 of the Income Tax Act, which restricts the deductibility of payments made by a taxpayer to a spouse or other relative who shares a common livelihood and is involved in the taxpayer's business. The case was particularly significant because it involved two independently practicing lawyers who were married and living together, raising questions about whether the professional independence of the recipient spouse could preclude the application of Article 56. The Supreme Court's ruling provided crucial clarification on this issue, affirming the broad application of the provision based on its explicit conditions.

The central issue was whether a lawyer, X, could deduct as necessary business expenses payments made to his spouse, A – also a lawyer operating her own independent practice – for legal services A provided to X's law practice, given that X and A shared a common livelihood. X argued that A's status as an independent professional should exempt such payments from the restrictions of Article 56, and further challenged the constitutionality of the provision if applied in such circumstances.

Facts of the Case

X, the appellant, was a lawyer registered with the B Bar Association and operated his law firm in Minato Ward, Tokyo. His spouse, A, was also a lawyer, registered with the C Bar Association, and ran her own independent law practice under a different firm name in Shinjuku Ward, Tokyo. A's law office had its own staff, office facilities, purchased books, and other expenses, all of which were accounted for separately from X's law firm expenses. X and A lived together and shared a common livelihood (生計を一にする, seikei o itsu ni suru).

For the years 1997, 1998, and 1999, X paid A 5.95 million yen annually as remuneration for legal work A performed in connection with X's business. X withheld income tax from these payments at the time they were made and subsequently filed his final income tax returns for these years, deducting the payments to A as necessary business expenses from his gross business income.

The tax office director, Y (the appellee), disallowed these deductions, asserting that the payments to A (referred to as "the弁護士報酬" or "lawyer's remuneration" in question) were not deductible as necessary expenses from X's gross income. Consequently, on December 25, 2000, Y issued reassessment dispositions for X's income tax for the years 1997 through 1999, along with underpayment penalty dispositions. (These dispositions were partially rescinded by an administrative review decision on February 5, 2002; the dispositions after this partial rescission are referred to as "the Dispositions in Question").

X filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the Dispositions in Question, arguing:

- Article 56 of the Income Tax Act should not apply when the person receiving the remuneration is engaged in the work as an independent business owner.

- If Article 56 is applied to remuneration paid by one spouse to another for work performed by the latter in the former's business, where both spouses are independently operating their own businesses, it would be excessively unreasonable and would violate Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution (guaranteeing equality under the law). X contended this unreasonableness was evident when compared to "blue form filers" (青色申告者, aoiro shinkokusha) who can deduct appropriate remuneration paid to family members as necessary expenses under Article 57 of the Income Tax Act, and also when compared to taxpayers who employ unrelated individuals.

The Tokyo District Court, as the court of first instance (judgment of June 27, 2003), dismissed X's claims. It held that Article 56 clearly applies if two conditions are met based on its literal wording: (1) the recipient of the payment is "a spouse or other relative sharing a common livelihood with the resident," and (2) the reason for payment is "engaging in the resident's business that generates real estate income, business income, or forestry income, or other similar reasons whereby payment is received from said business". The court stated that neither Article 56 nor any other provision in the Income Tax Act suggests that its application is affected by individual circumstances such as the nature of the recipient relative's business, whether the relative is dependently or independently engaged, the reason for payment, or the appropriateness of the remuneration amount. Thus, as long as these two conditions are met, Article 56 should apply regardless of individual circumstances.

X appealed, but the Tokyo High Court (judgment of October 15, 2003) also dismissed the appeal, leading X to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the decisions of the lower courts. The Court provided detailed reasoning concerning both the interpretation of Article 56 and its constitutionality.

Interpretation and Application of Article 56

The Supreme Court first elaborated on the purpose and mechanics of Article 56 of the Income Tax Act:

- The Court stated that Article 56 is designed to address situations where a person closely related to a resident taxpayer engaged in business receives payment in connection with that business. If such payments were freely allowed as necessary expenses in calculating the resident's business income, it could lead to imbalances in tax burdens among taxpayers.

- To prevent this, Article 56 stipulates that when a spouse or other relative who shares a common livelihood with the resident engages in the resident's business (which generates business income, etc.) or receives payment from said business for other reasons, the amount equivalent to such payment shall not be included as a necessary expense in calculating the resident's business income.

- Concomitantly, Article 56 provides that any amount that should be included as necessary expenses in calculating the various types of income of the relative (related to that payment) shall instead be included as a necessary expense in calculating the business income of the resident taxpayer.

- Based on this legislative intent and the explicit wording of Article 56, the Supreme Court concluded that even if a spouse or other relative who shares a common livelihood with the resident also operates a separate business independently, this fact alone cannot be a reason to negate the application of Article 56. As long as the requirements stipulated in Article 56 are met, the provision applies.

Constitutionality (Article 14, Paragraph 1) and Relation to Article 57

The Supreme Court then addressed X's argument that Article 56 was unconstitutional:

- The Court affirmed that the legislative purpose of Article 56, as described above, is legitimate.

- The specific requirements laid out in Article 56 are intended to clarify the scope of its application and to enable straightforward and simple tax administration. In this context, the requirements are not unreasonable in relation to the legislative purpose.

- Furthermore, considering that Article 56 itself includes measures for necessary expense deductions (i.e., allowing the relative's expenses related to the payment to be deducted from the resident's business income), the rationality of Article 56 cannot be denied.

- The Court then discussed Article 57, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act. This provision allows a resident who is a "blue form filer" (approved by the tax office director) to deduct as necessary expenses salaries paid to a spouse or other relative sharing a common livelihood who is exclusively engaged in the resident's business, provided certain conditions are met and the amount is deemed reasonable remuneration for the labor in light of circumstances specified by cabinet order. Article 57, Paragraph 3 also allows a certain amount of deduction for taxpayers other than blue form filers if they have a spouse or relative sharing a common livelihood who is exclusively engaged in their business.

- The Supreme Court explained that these provisions in Article 57 were established with the pre-existing framework of Article 56 in mind. A key consideration for enacting Article 57 was to prevent tax burden imbalances between individuals operating businesses and those operating businesses as corporations.

- Given the purpose and content of Article 57, the Court concluded that the Income Tax Act's approach of limiting exceptions to Article 56 only to the cases specified in Article 57 is not "manifestly unreasonable" (著しく不合理であることが明らかであるとはいえない).

- Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the Dispositions in Question did not misapply Article 56 and were not in violation of Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution. The Court noted that this conclusion was consistent with the spirit of a previous Grand Bench ruling (Supreme Court, Showa 55 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 15, judgment of March 27, 1985). The High Court's judgment was deemed correct and free of the asserted legal violations.

Commentary Insights

The "Lawyer Couple Case" and its judgment have been subjects of considerable legal commentary, particularly regarding the evolution and modern applicability of Article 56.

Historical Background and Legislative Intent of Article 56

Article 56 of the Income Tax Act has historical roots in the post-World War II tax reforms influenced by the Shoup Recommendations of 1949. These recommendations advocated for a shift from the then-prevailing household unit taxation system (世帯単位課税, setai tan'i kazei) to a system of individual unit taxation (個人単位課税, kojin tan'i kazei). However, to prevent potential tax avoidance loopholes for "savvy taxpayers," the Shoup report also suggested specific anti-avoidance measures. These included (1) aggregating the asset income of cohabiting spouses and minor children with the taxpayer's income for reporting and taxation, and (2) aggregating the income of spouses and minor children employed in the taxpayer's business with the taxpayer's income. The current Article 56 is an evolution of provisions first introduced in the 1950 tax system reforms following these recommendations. The primary purpose of Article 56 is thus understood to be the prevention of arbitrary income dispersion among cohabiting family members that could arise from a strict application of individual taxation, thereby ensuring fairness.

Significance of the Ruling in Context

Many previous court cases concerning Article 56 involved situations where the relative receiving payments from the taxpayer's business had a limited degree of independence. The "Lawyer Couple Case" was distinct because it concerned payments between two highly qualified professionals, each operating their own independent law practice.

This case gained prominence partly because a similar case being litigated around the same time, known as the "Lawyer/Tax Accountant Couple Case" (where a lawyer paid remuneration to his wife, a tax accountant, for services), initially saw a different outcome at the District Court level. In that initial ruling (Tokyo District Court, July 16, 2003), the court held that Article 56's phrase "engaged in...or other reasons whereby payment is received from said business" referred to situations where the relative participated in the business in a subordinate capacity, was employed as an employee, or similar dependent roles. It suggested that if a relative provided services as an independent contractor based on a transaction with the taxpayer's business, Article 56 would not apply. This differing initial judgment fueled debate on the precise scope of Article 56's application.

However, in the "Lawyer Couple Case" (the present case), the courts consistently held, from the District Court through to the Supreme Court, that Article 56 applies as long as its two explicit statutory conditions are met: (1) the recipient is a spouse or other relative sharing a common livelihood with the resident taxpayer, and (2) the payment is for engaging in the resident's business generating relevant income categories, or for other reasons leading to payment from that business. The independence of the spouse's or relative's own business activities was not considered a factor that would negate the application of Article 56.

Ultimately, the "Lawyer/Tax Accountant Couple Case" also saw its initial District Court ruling overturned on appeal (Tokyo High Court, June 9, 2004), and its subsequent Supreme Court decision (July 5, 2005) cited the judgment in this "Lawyer Couple Case." It affirmed that Article 56 applies even when the cohabiting spouse or relative operates a separate business. With these two Supreme Court judgments, the interpretation regarding the scope of application of Article 56 was largely considered settled.

Reconsideration in Light of Modern Societal Changes

Commentary also reflects on the contemporary relevance of Article 56. It is pointed out that at the time of Article 56's enactment, many individual businesses in Japan were operated as family units, often under the de facto control of the head of the household (usually the business owner). In such an environment, there was often no established practice of paying formal remuneration to family members engaged in the business, or if payments were made, it was difficult to assess their reasonableness or legitimacy as genuine compensation.

However, significant transformations in Japanese society, including changes in family structures, evolving marital relationships, and the increased participation of women in the workforce and professions, have led to critiques of Article 56. Critics argue that the provision may no longer align with current social realities and could even act as a tax-related constraint on women's societal and economic advancement. While Japan's Tax Commission has engaged in discussions about creating a tax system that is neutral with respect to different working styles, Article 56 itself has not recently been a direct subject of proposed legislative reforms, though some legal scholars and practitioners continue to advocate for changes.

Broader Implications and Discussion

The Supreme Court's decision in the "Lawyer Couple Case" has several broad implications:

- Strict Application of Statutory Conditions: The ruling confirms that Article 56 is applied strictly based on its literal conditions: (1) the recipient of the payment is a spouse or other relative sharing a common livelihood with the taxpayer, and (2) the payment is for the relative's engagement in the taxpayer's business (or other reasons leading to payment from that business).

- Limited Role for "Independence" Argument: The professional independence of the recipient spouse, or the fact that they operate their own separate business, does not automatically exclude the application of Article 56 if the above conditions are met. This was a key point affirmed by the Supreme Court.

- Rationale of Article 56: The Court upheld the legitimacy of Article 56's purpose – preventing artificial income splitting within a family unit that shares finances, ensuring clarity in tax law, and simplifying tax administration.

- Article 57 as Limited Relief: The judgment reinforces that Article 57 (providing for deductions of salaries to exclusively engaged family members for blue form filers, and a smaller allowance for others) constitutes a specific, limited exception to the general rule in Article 56. The conditions for Article 57, such as exclusive engagement, must be met for this relief to apply.

- Potential Disincentives: While legally sound from the Court's perspective, the application of Article 56 in such scenarios can be perceived as a disincentive for spouses who are both professionals to formally engage each other's services, even if doing so would be economically efficient or logical from a business standpoint.

The "Considerations for Discussion" section in the provided commentary raises the question of how Article 56 might be reformed to maintain its anti-abuse function while being minimally restrictive, within an individual unit taxation system. This reflects an ongoing debate about balancing tax fairness, administrative simplicity, and the evolving nature of family businesses and professional collaborations in modern society.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 2, 2004, judgment in the "Lawyer Couple Case" decisively clarified that Article 56 of the Income Tax Act applies to payments made by a taxpayer to a spouse who shares a common livelihood for services rendered to the taxpayer's business, even if that spouse is an independent professional operating their own separate business. The Court underscored the provision's legitimate legislative purpose of preventing tax avoidance through income splitting and ensuring fairness among taxpayers. It also confirmed that the limited exceptions provided under Article 57 for payments to family members are distinct and require specific conditions to be met. This ruling remains a cornerstone in understanding the scope of Article 56 and its implications for married professionals and family businesses in Japan.