In Your Pocket, But Not in Use: How Japan's High Court Defined the Crime of Using a Forged Document

Imagine a person is carrying a fake ID in their wallet. Are they committing a crime simply by walking down the street with it? This question becomes even more pointed in the context of driving a car. The law requires a driver to carry their license at all times. If a person drives a car while carrying a forged driver's license, does the act of driving itself transform the passive "carrying" of the document into the active, criminal "use" of it?

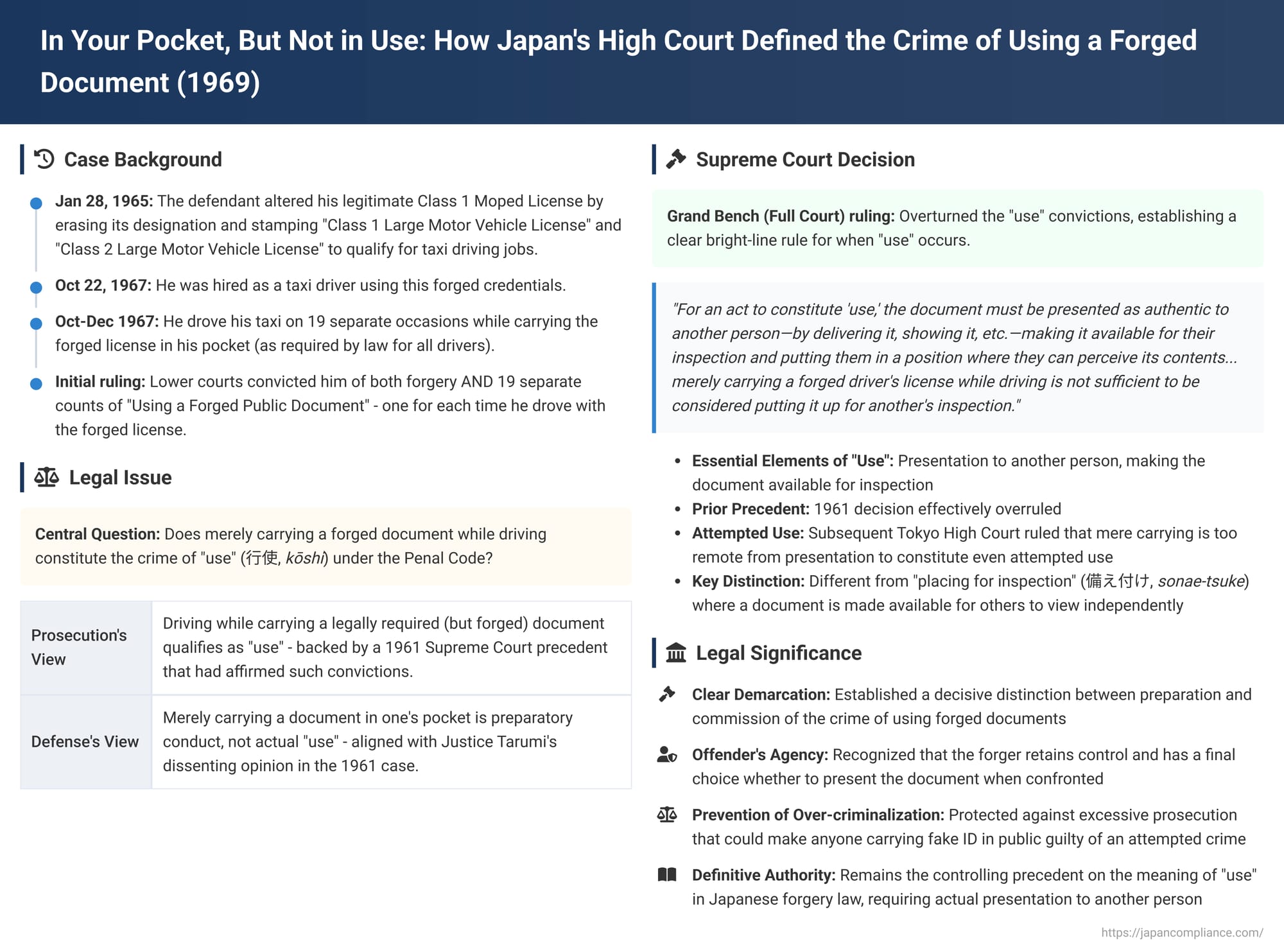

This fundamental question—about the precise moment an offender "uses" a forged document—was the subject of a landmark ruling by the full Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on June 18, 1969. The decision, which overturned a prior precedent, drew a clear and enduring line between preparing to deceive and the actual commission of the crime, a distinction that remains a cornerstone of Japanese forgery law.

The Facts: The Taxi Driver with the Fake License

The case involved a defendant who sought to work as a professional driver and devised a plan to obtain the necessary credentials illegally.

- The Forgery: On January 28, 1965, a day after receiving a legitimate Class 1 Moped License from the Fukuoka Prefectural Public Safety Commission, the defendant set about altering it. With the intent to use it for employment, he erased the words "Class 1 Moped License" and, using a set of typeset letters, stamped "Class 1 Large Motor Vehicle License" in its place. He also added a "Class 2 Large Motor Vehicle License" to the second category on the license.

- The Employment: On October 22, 1967, he was hired as a taxi driver.

- The Alleged "Use": Between that date and December 1, 1967, the defendant drove his taxi on 19 separate occasions. During each of these instances, he carried the forged driver's license with him, as required by law for all drivers.

The lower courts convicted the defendant not only of the initial act of forgery but also of 19 separate counts of Using a Forged Public Document—one count for each time he drove his taxi while carrying the fake license. This set the stage for a Supreme Court showdown over the legal meaning of "use."

The Legal Question: Is Carrying a Document the Same as Using It?

The core legal question was whether the act of driving while carrying a legally required (but forged) document constitutes the crime of "use" (kōshi) under the Penal Code. Prior to this case, the Supreme Court's position was ambiguous. A 1961 decision had affirmed a conviction in a similar case, leading many to believe that the Court considered driving-while-carrying to be "use." However, that 1961 ruling included a powerful dissenting opinion from Justice Tarumi, who argued that merely carrying a document in one's pocket was not enough to constitute "use." The 1969 Grand Bench case would ultimately resolve this conflict.

The Supreme Court Grand Bench's Landmark Ruling

In a major decision that changed the course of forgery law, the Grand Bench overturned the lower courts' convictions for "use." It established a clear, bright-line rule that definitively answered the question. The Court held:

The crime of Using a Forged Public Document is intended to prevent the concrete infringement of public trust in the authenticity of documents. Therefore, for an act to constitute "use," the document must be presented as authentic to another person—by delivering it, showing it, etc.—making it available for their inspection and putting them in a position where they can perceive its contents... Accordingly, even though the law stipulates a duty to carry a driver's license when operating a motor vehicle and to present it in certain circumstances, in a situation where one merely carries a forged driver's license while driving, this is not sufficient to be considered putting it up for another's inspection, and it should be understood as not constituting the crime of Using a Forged Public Document.

Analysis: The Line Between Preparation and Commission

The Supreme Court's ruling provided a crucial and logical distinction between the potential for deception and the actual act of it.

- The Offender's Final Choice: The Court's logic recognizes that as long as the forged document remains in the defendant's possession, he retains control. If he were to be stopped by a police officer, he still has a choice: he can present the forged license and commit the crime of "use," or he can refuse to present it (or confess to being unlicensed) and face a different, lesser charge. The crime of "use" is only complete when he takes that final, voluntary step of presenting the document to another person.

- The Distinction from "Placing for Inspection": This reasoning distinguishes "carrying" from a separate legal concept known as "placing for inspection" (sonae-tsuke). In previous cases, the courts had held that "use" occurs when a forger places a fake document, such as a forged ledger, in an office where it can be viewed by authorized persons, or causes a false entry to be made in a public registry open to public inspection. In those scenarios, the document is made available for others to view independently of any further action by the forger. In contrast, a license carried in a pocket requires the forger's active participation to be seen.

- The Question of Attempted Use: If carrying is not the completed crime, could it be an attempted use? This question was also settled in the wake of the Grand Bench decision. A subsequent Tokyo High Court ruling, along with the majority of legal scholars, concluded that it is not. Mere carrying is considered too remote from the actual act of presentation to constitute a criminal attempt. An attempt would require a more direct action, such as reaching for one's wallet to retrieve the license upon being asked by an officer. To rule otherwise would risk over-criminalization, potentially making anyone who simply carries a fake ID in public guilty of an attempted crime.

Conclusion

The 1969 Grand Bench decision remains the definitive authority on the meaning of "use" in Japanese forgery law. It established that the crime is not committed by mere possession or carrying, even when there is a legal duty to have the document ready for inspection. The crime of "use" is only completed when the forger takes the crucial, additional step of presenting the document to another person, thereby putting the public's trust in its authenticity at concrete risk. This ruling provides a clear and logical distinction between preparing to deceive and the actual act of deception—a fundamental principle not only in forgery law but across the entire landscape of criminal justice.