Immediate Acquisition of Movables in Japan: Is "Constructive Possession" Enough?

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of February 11, 1960 (Showa 35) (Case No. 1092 (O) of 1957 (Showa 32))

Subject Matter: Claim for Confirmation of Movable Ownership, Delivery thereof, etc. (動產所有権確認同引渡等請求事件 - Dōsan Shoyūken Kakunin Dō Hikiwatashi tō Seikyū Jiken)

Introduction

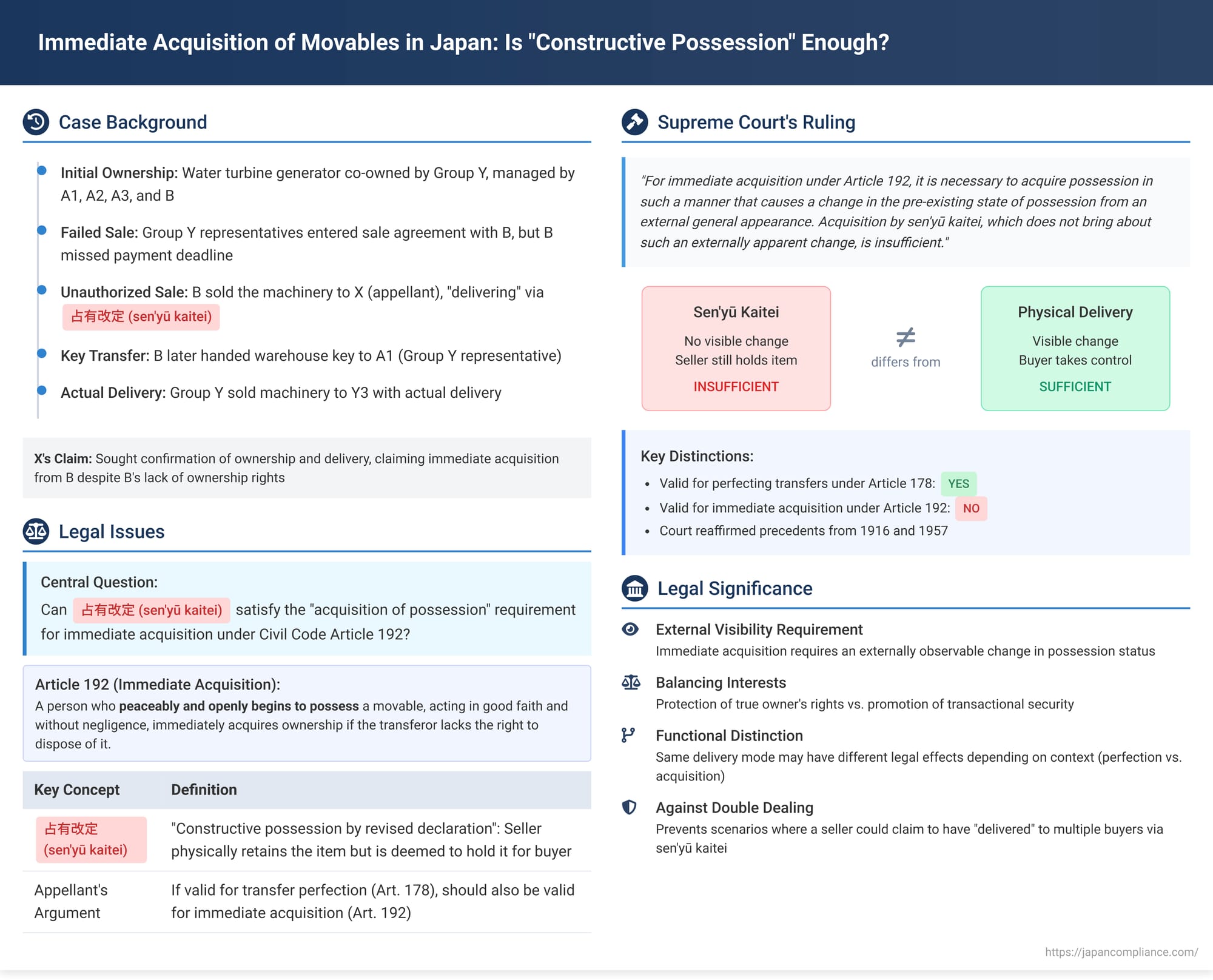

This article analyzes a 1960 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that addresses a critical aspect of acquiring ownership of movable property from a person who does not have the right to dispose of it. This legal doctrine, known as "immediate acquisition" or "bona fide acquisition" (即時取得 - sokuji shutoku) under Article 192 of the Civil Code, allows a good faith acquirer to obtain ownership under certain conditions. A key condition is the acquisition of "possession." This case specifically examines whether "constructive possession by revised declaration" (占有改定 - sen'yū kaitei), a form of delivery where the seller retains physical control of the goods but is deemed to hold them for the buyer, satisfies the possession requirement for immediate acquisition. The Supreme Court reaffirmed the established precedent that it does not.

The dispute involved X (appellant/plaintiff), who claimed to have acquired ownership of a water turbine generator and associated machinery through immediate acquisition, and Group Y (appellees/defendants), who were the original co-owners or their successors/representatives and who later re-took possession of the equipment.

Factual Background

A water turbine generator and its ancillary machinery and tools (the "Movables") were co-owned by some residents of a village in Okayama Prefecture (collectively, "Group Y," the original owners). This equipment was managed by individuals A1, A2, A3, and B. B held the key to the warehouse where the Movables were stored.

The representatives of Group Y (A1, A2, and A3) entered into a sales agreement for the Movables with B personally. This agreement stipulated that the contract would become void if B failed to pay the purchase price by a specified date. B did not complete the payment by the deadline. Despite this, B, purporting to be the owner of the Movables, subsequently entered into a sales contract for the same Movables with X (the appellant). X, believing B to be the true owner, paid the purchase price to B. The "delivery" of the Movables from B to X was effected by "sen'yū kaitei" – an arrangement where B, who continued to physically possess the Movables, was deemed to be holding them on behalf of X.

Sometime later, A1, A2, and A3 designated A1 as the sole representative for Group Y. B agreed to this and handed over the warehouse key to A1. Subsequently, A1, acting as Group Y's representative and through the mediation of Y2 (one of the defendants), sold the Movables to Y3 (another defendant, representing or part of Group Y), and the full price was received by A1. It appears effective control or actual delivery was made to Y3.

When X later attempted to remove the Movables from the warehouse, he was prevented by members of Group Y, and Y3 ultimately took possession of the equipment. X then filed a lawsuit against Y1, Y2, and Y3 (referred to collectively as Group Y in the appeal context), seeking confirmation of his ownership of the Movables, their delivery, and, alternatively, compensation if delivery was impossible.

The lower courts (both first instance and appellate) dismissed X's claim. The appellate court found that B had not acquired ownership from the original owners (Group Y's representatives A1, A2, A3) because he failed to pay the price as agreed. Therefore, B was an unauthorized person (無権利者 - mukenrisha) when he purported to sell to X. Furthermore, the appellate court held that the "delivery" of the Movables from B to X was merely by "sen'yū kaitei." It ruled that immediate acquisition under Article 192 of the Civil Code cannot be based on "sen'yū kaitei." X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that since "sen'yū kaitei" is a valid form of delivery for perfecting a transfer of movables under Article 178 of the Civil Code, it should also be considered sufficient "acquisition of possession" for the purposes of immediate acquisition under Article 192.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, affirming the appellate court's decision.

The Court's reasoning was concise and directly addressed the legal effect of "sen'yū kaitei" in the context of immediate acquisition:

"When movables are acquired from an unauthorized person, for the transferee to be able to acquire ownership under Article 192 of the Civil Code, it is necessary to acquire possession in such a manner that causes a change in the pre-existing state of possession from an external general appearance. It must be said that acquisition by the so-called method of 'sen'yū kaitei,' which does not bring about such an externally apparent change, is insufficient."

The Supreme Court cited two key precedents from the Great Court of Cassation (Daishin'in): a judgment from May 16, 1916 (Taisho 5), and its own more recent Second Petty Bench judgment from December 27, 1957 (Showa 32). These precedents had established the rule that "sen'yū kaitei" does not suffice for immediate acquisition.

The appellate court had found that X purchased the Movables from B, but B was an unauthorized person at the time. It also found that although B "delivered" the Movables to X, this delivery was by "sen'yū kaitei." Meanwhile, the Movables were subsequently sold by A1 (representing the true owners, Group Y) to Y3 (also part of Group Y), with full payment and actual delivery completed. Given these facts, the Supreme Court held that the appellate court was correct in denying X's claim of ownership through immediate acquisition and, consequently, dismissing X's lawsuit.

The Supreme Court found that X's arguments were based on a contrary position regarding the interpretation and application of Article 192 and essentially amounted to a criticism of the lower court's lawful fact-finding, and thus could not be adopted.

Analysis and Implications

This 1960 Supreme Court judgment is a significant reaffirmation of a long-standing principle in Japanese law concerning the requirements for immediate acquisition (bona fide purchase) of movables under Article 192 of the Civil Code.

- Immediate Acquisition (Sokuji Shutoku - Article 192): This doctrine allows a person who, in good faith and without negligence, peaceably and openly begins to possess a movable, believing the transferor to be the owner with the right to dispose of it, to immediately acquire the ownership of that movable, even if the transferor was not the true owner or lacked the authority to sell. It is a crucial rule for protecting the security of transactions involving movable property.

- Requirement of "Acquisition of Possession": A core requirement for immediate acquisition is that the acquirer must "begin to possess" the movable. The legal debate, as highlighted by this case, centers on what types of "possession" satisfy this requirement.

- "Sen'yū Kaitei" (Constructive Possession by Revised Declaration) is Insufficient for Immediate Acquisition: The clear and unwavering rule established by the Daishin'in and consistently upheld by the post-war Supreme Court is that "sen'yū kaitei" does not meet the "acquisition of possession" requirement for immediate acquisition under Article 192.

- Rationale – Lack of External Change: The primary reason cited in the precedents (and implied here) is that "sen'yū kaitei" does not involve any outward, observable change in the state of possession. The transferor (the unauthorized seller) continues to physically hold the goods. The agreement that they now hold for the transferee is purely internal between those two parties and is not apparent to the outside world, including the true owner. The courts have emphasized that for immediate acquisition, there must be a change in possession that is, at least in principle, externally recognizable.

- Distinction from "Delivery" as a Perfection Requirement (Article 178): This is where a key distinction lies. Under Article 178, "delivery" is required to perfect a transfer of rights in movables so it can be asserted against third parties. The Civil Code recognizes several forms of delivery, including actual physical delivery (Article 182(1)), simplified delivery (Article 182(2)), delivery by direction (Article 184), and "sen'yū kaitei" (Article 183). While "sen'yū kaitei" is a valid form of delivery for perfecting a transfer of ownership between a rightful owner and a buyer, it is not considered sufficient "acquisition of possession" to trigger the extraordinary protection of immediate acquisition when the seller is unauthorized.

- The PDF commentary on this case points out that scholarly opinion was once divided, with some arguing that if "sen'yū kaitei" is a valid delivery under Article 178, it should also count for Article 192. However, the prevailing judicial view and much of modern scholarship differentiate the policy considerations. Article 178 deals with perfecting an otherwise valid transfer; Article 192 deals with an exceptional acquisition from a non-owner, requiring a higher standard of public visibility in the change of possession to protect the true owner.

- Protecting the True Owner: The rule denying immediate acquisition through "sen'yū kaitei" serves to offer greater protection to the true owner of the movables. If a mere internal agreement between an unauthorized possessor and a buyer could divest the true owner of their title, it would significantly weaken property rights. Requiring a more tangible change in possession (like actual delivery or at least simplified delivery where the buyer is already holding the item) provides a better balance.

- Policy Considerations: Transactional Security vs. True Owner's Rights: The doctrine of immediate acquisition itself aims to promote transactional security by protecting bona fide purchasers. However, limiting it by excluding "sen'yū kaitei" reflects a balancing act. The law deems that the level of reliance deserving protection under Article 192 requires a more concrete change in the possessory status than what "sen'yū kaitei" provides. The risk that the person retaining physical possession (the unauthorized seller in a "sen'yū kaitei" scenario) might engage in further unauthorized dealings (e.g., a second sale with actual delivery) is a significant factor.

This Supreme Court decision solidifies the interpretation that while "sen'yū kaitei" can effect a transfer of possession between parties for some purposes (like perfecting a sale from a rightful owner), it does not provide the robust, externally apparent change in possession necessary to enable a buyer to immediately acquire ownership from an unauthorized seller under Article 192. For immediate acquisition, a more tangible form of taking possession is required.