Illegal Permit, No Crime? Japan's Supreme Court on Abusive Administrative Acts and Criminal Liability

A Second Petty Bench Ruling from June 16, 1978

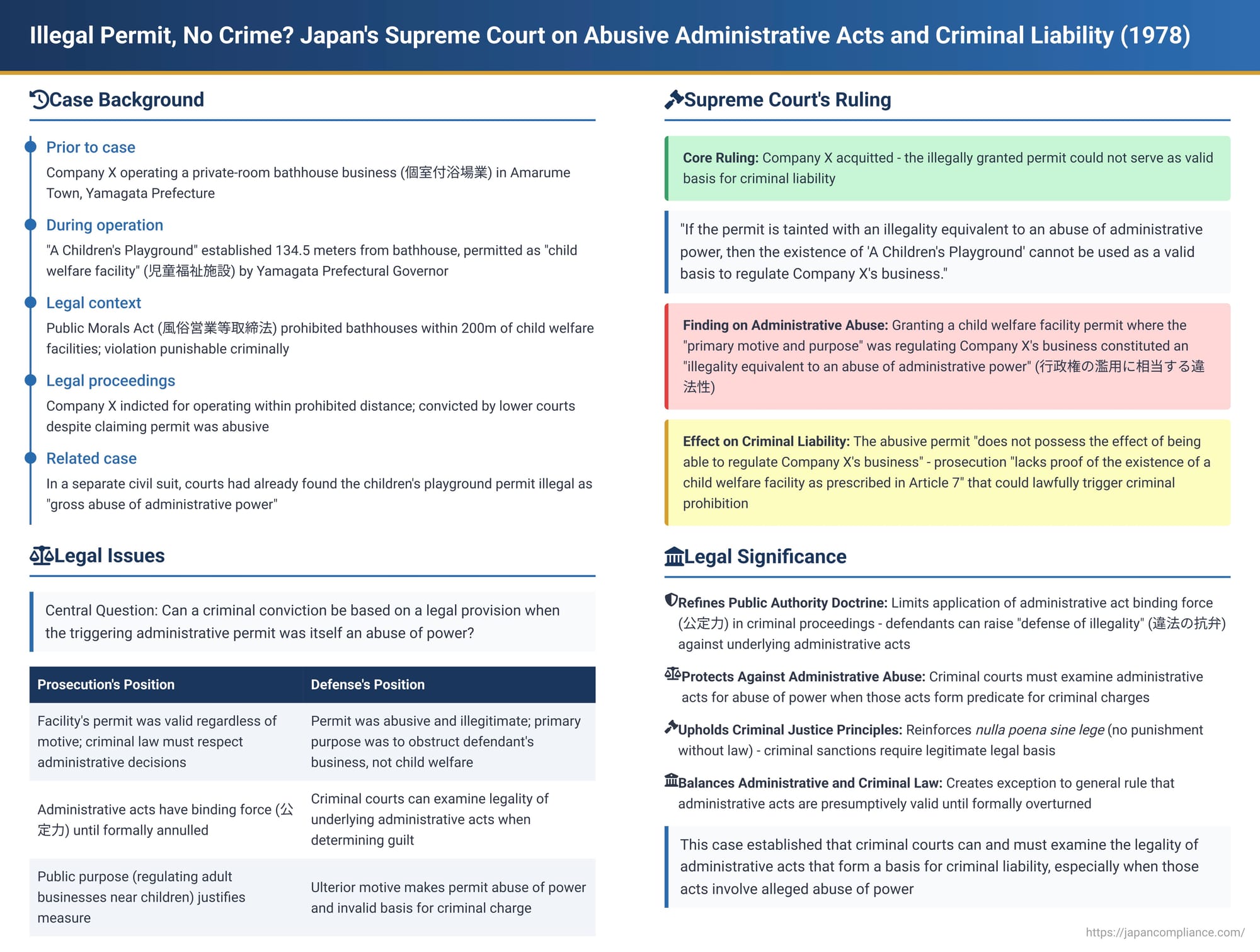

Many areas of business and social life are regulated by administrative laws, and these laws often include criminal penalties to ensure compliance. But what happens if the underlying administrative decision—such as the granting of a permit whose existence triggers a prohibition, or the issuance of an order whose violation is punishable—is itself illegal? Can an individual or company still be criminally convicted? A 1978 decision by the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan (Showa 50 (A) No. 24) addressed this critical intersection of administrative law and criminal liability, particularly in a case involving an adult entertainment business and a controversially permitted child welfare facility.

The Facts: Bathhouse vs. Playground

Defendant Company X operated a private-room bathhouse business (個室付浴場業 - koshitsutsuki yokujōgyō), a type of adult entertainment establishment, in Amarume Town, Yamagata Prefecture. Nearby, at a distance of 134.5 meters, a facility known as "A Children's Playground" (A児童遊園 - A Jidō Yūen) had been established and officially permitted as a "child welfare facility" (児童福祉施設 - jidō fukushi shisetsu) under the Child Welfare Act (児童福祉法 - Jidō Fukushi Hō) by the Yamagata Prefectural Governor.

The legal problem arose under the Act on Control of Businesses Affecting Public Morals (風俗営業等取締法 - Fūzoku Eigyō-tō Torishimari Hō, commonly known as Fūeihō). At the time (under a pre-1984 version of the Act), Article 4-4, paragraph 1, generally prohibited the operation of private-room bathhouses within a 200-meter radius of certain protected facilities, including child welfare facilities. Violations of this prohibition were subject to criminal penalties for both the individual operator and, if applicable, the corporate body (under Articles 7(2) and 8 of the Act at the time; current provisions are Arts. 49(v) and 56).

Company X was indicted for violating this provision by operating its bathhouse business in close proximity to the newly permitted "A Children's Playground."

The Defense: An Illegitimate "Child Welfare Facility"?

In its defense, Company X launched a significant challenge against the legality and effect of the permit granted for "A Children's Playground." The core arguments were:

- The facility, "A Children's Playground," did not substantively meet the necessary requirements to qualify as a genuine child welfare facility.

- More critically, the permit issued by the Yamagata Prefectural Governor for "A Children's Playground" was an abuse of administrative power. The defense alleged that the primary motivation behind the town's application for the permit, and the Governor's granting of it, was not genuine concern for child welfare but rather a targeted effort to obstruct or shut down Company X's pre-existing private-room bathhouse business. Such an abuse of power, they argued, rendered the permit absolutely void.

- Even if the permit was not absolutely void, it should not be treated as a valid and effective legal basis for regulating Company X's business, given the improper circumstances surrounding its issuance. (It is noteworthy that, as pointed out in the Supreme Court's judgment and legal commentary, in a separate civil lawsuit for damages brought by Company X against Yamagata Prefecture, the permit for "A Children's Playground" had indeed been found illegal by the courts, including the Supreme Court, as a gross abuse of administrative power, and the prefecture had been held liable for damages ).

The lower courts in the criminal proceeding, however, had convicted Company X.

- The Sakata Summary Court (first instance) found Company X guilty and imposed a fine, presupposing that the permit for "A Children's Playground" was valid.

- The Sendai High Court, Akita Branch (second instance), upheld the conviction. While it acknowledged that Amarume Town had applied for the facility permit primarily motivated by a desire to regulate Company X's business, and that the Governor was aware of this motivation when granting the permit, the High Court nevertheless found the permit to be a lawful exercise of power, viewing it as a legitimate restriction on the freedom of business for the sake of public welfare.

The Supreme Court's Decision of June 16, 1978

The Supreme Court overturned the convictions by the lower courts and acquitted Defendant Company X. Its reasoning hinged on the illegality of the administrative permit for the child welfare facility and the impact of that illegality on the criminal charge.

Core Reasoning:

- Interplay of the Fūzoku Eigyō Hō and the Child Welfare Facility Permit: The Court first noted that the Fūzoku Eigyō Hō, while generally prohibiting businesses like Company X's near facilities like schools or child welfare institutions, did not create an absolute, exceptionless ban (it referenced Article 4-4, paragraph 3 of the Act, which allowed for exceptions). This implied that the legitimacy of the "protected facility" was a relevant consideration. The Court stated: "if the permit for 'A Children's Playground,' which preceded Company X's business operation [or whose existence triggered the prohibition against X], is tainted with an illegality equivalent to an abuse of administrative power, then the existence of 'A Children's Playground' cannot be used as a valid basis to regulate Company X's business."

- Illegality of the Child Welfare Facility Permit: The Supreme Court then directly addressed the legality of the permit for "A Children's Playground."

- It emphasized that the purpose of a children's playground, as defined by Article 40 of the Child Welfare Act, is "to provide children with healthy play, thereby promoting their health and enriching their sentiments." Any application for, or granting of, a permit for such a facility must align with this genuine child welfare purpose.

- The Court acknowledged the finding of the lower criminal court (the Sendai High Court) that Amarume Town's application for the permit was primarily motivated by the desire to regulate Company X's bathhouse business, and that the Governor granted the permit fully aware of this background.

- The Supreme Court concluded that granting a permit for a child welfare facility where the "primary motive and purpose" was actually the regulation of Company X's pre-existing business constituted an "illegality equivalent to an abuse of administrative power" (行政権の濫用に相当する違法性 - gyōseiken no ranshin ni sōtōsuru ihōsei).

- Such a permit, tainted by this abuse of power, "does not possess the effect of being able to regulate Company X's... business." The Court also explicitly referenced the final judgment in the separate civil case where this same permit had already been definitively found illegal as a "gross abuse of administrative power".

- Conclusion on Criminal Liability: Based on the finding that the permit for "A Children's Playground" was an abuse of power and thus could not serve as a lawful basis for restricting Company X's business:

- The prosecution, in the criminal case against Company X, therefore "lacks proof of the existence of a child welfare facility as prescribed in Article 7 of the Child Welfare Act that could regulate" Company X's operations.

- Consequently, Company X should be acquitted of the charge. The lower courts had erred in finding Company X guilty because they had misjudged the legal effect of the fundamentally flawed administrative disposition (the facility permit).

Key Legal Principles: Kōteiryoku and the "Defense of Illegality" in Criminal Cases

This case touches upon the important Japanese administrative law doctrine of kōteiryoku (公定力), often translated as "authoritative binding force" or "public authority."

- Kōteiryoku: This principle generally holds that an administrative act, even if it contains some illegality, is treated as valid and effective by other state organs (including courts in unrelated proceedings) and by the public, until it is formally cancelled or withdrawn by a competent authority (e.g., the issuing agency itself, a higher administrative review body, or a court in a direct annulment action). The main exception is if the illegality is so "grave and obvious" (重大かつ明白な瑕疵 - jūdai katsu meihaku na kashi) that the act is considered null and void from its very beginning (ab initio). (See Supreme Court, Dec. 26, 1955 – an earlier case also discussed in this series ).

- "Defense of Illegality" (Ihō no Kōben) in Criminal Cases: The application of kōteiryoku in criminal proceedings has been a subject of considerable debate. The prevailing view in modern Japanese legal theory, supported by this 1978 Supreme Court judgment, is that the full force of kōteiryoku does not necessarily extend to criminal proceedings where an administrative act forms a predicate for the crime. A defendant in a criminal case can raise the "defense of illegality" concerning the underlying administrative act. If the criminal court finds the administrative act to be significantly illegal (e.g., an abuse of power, or lacking essential legal basis), this can lead to an acquittal, as it means an essential element of the crime (e.g., violation of a lawful order, or operation near a lawfully established facility) is not met.

- Rationales for Allowing this Defense: The commentary suggests several rationales for permitting this defense in criminal cases, including the need to protect the human rights of the accused, the requirement for strict legality in criminal punishment (nulla poena sine lege – no penalty without law), and the injustice of punishing someone for disobeying an unlawful administrative act before they have had a chance to have it annulled through often lengthy administrative or judicial review processes.

Abuse of Administrative Power (行政権の濫用 - Gyōseiken no Ranyō)

A central finding in this case was that the permit for the child welfare facility constituted an "abuse of administrative power."

- This means that even if an administrative act appears formally correct on its face, it can still be deemed illegal if its underlying purpose is improper or if it represents a misuse of the discretion granted to the administrative agency.

- Here, the Supreme Court agreed that the primary motive behind permitting "A Children's Playground" was not the promotion of child welfare but rather the strategic creation of a "protected facility" to enable the authorities to take action against Company X's pre-existing business. This ulterior motive rendered the permit an abuse of power.

Impact on Criminal Enforcement of Administrative Regulations

This 1978 Supreme Court decision is a landmark precedent affirming that criminal courts in Japan can, and indeed must, examine the legality of predicate administrative acts when determining criminal guilt.

- It does not mean that any minor or technical flaw in an administrative act will automatically lead to an acquittal in a related criminal case.

- However, where the illegality is substantial, such as an abuse of power that undermines the very foundation for the criminal prohibition, it can negate criminal liability. The focus is on whether the administrative act can legally serve as the basis for the specific criminal charge.

- The commentary notes that the Supreme Court, in this case, did not explicitly discuss kōteiryoku but rather directly assessed the illegality of the permit and its consequence for the criminal charge. It effectively found that, for the purpose of prosecuting Company X, the illegally granted permit had no regulatory effect.

Significance of the Ruling

This ruling has several important implications:

- It provides a significant safeguard against the misuse of administrative powers, ensuring that actions taken for improper or ulterior motives cannot easily become the basis for criminal sanctions.

- It reinforces the principle that the criminal justice system must independently assess all elements of an offense, including the legality of underlying administrative acts where relevant.

- It clarifies that the effectiveness of an administrative act for the purpose of grounding a criminal charge is contingent on its substantive legality, particularly its freedom from defects like an abuse of power.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1978 acquittal of Company X is a crucial decision that illustrates the judiciary's role in scrutinizing administrative actions, even within the context of a criminal trial. It underscores the principle that criminal liability cannot be founded upon an administrative act that is itself the product of a significant abuse of power. By focusing on the improper motive behind the granting of the child welfare facility permit, the Court ensured that the coercive power of criminal law was not used to enforce an administrative decision that lacked a legitimate public purpose. This case remains a vital precedent for understanding the interplay between administrative legality and criminal justice in Japan.