Human Rights in Japanese Supply Chains: Contractual Strategies and Legal Liabilities

TL;DR

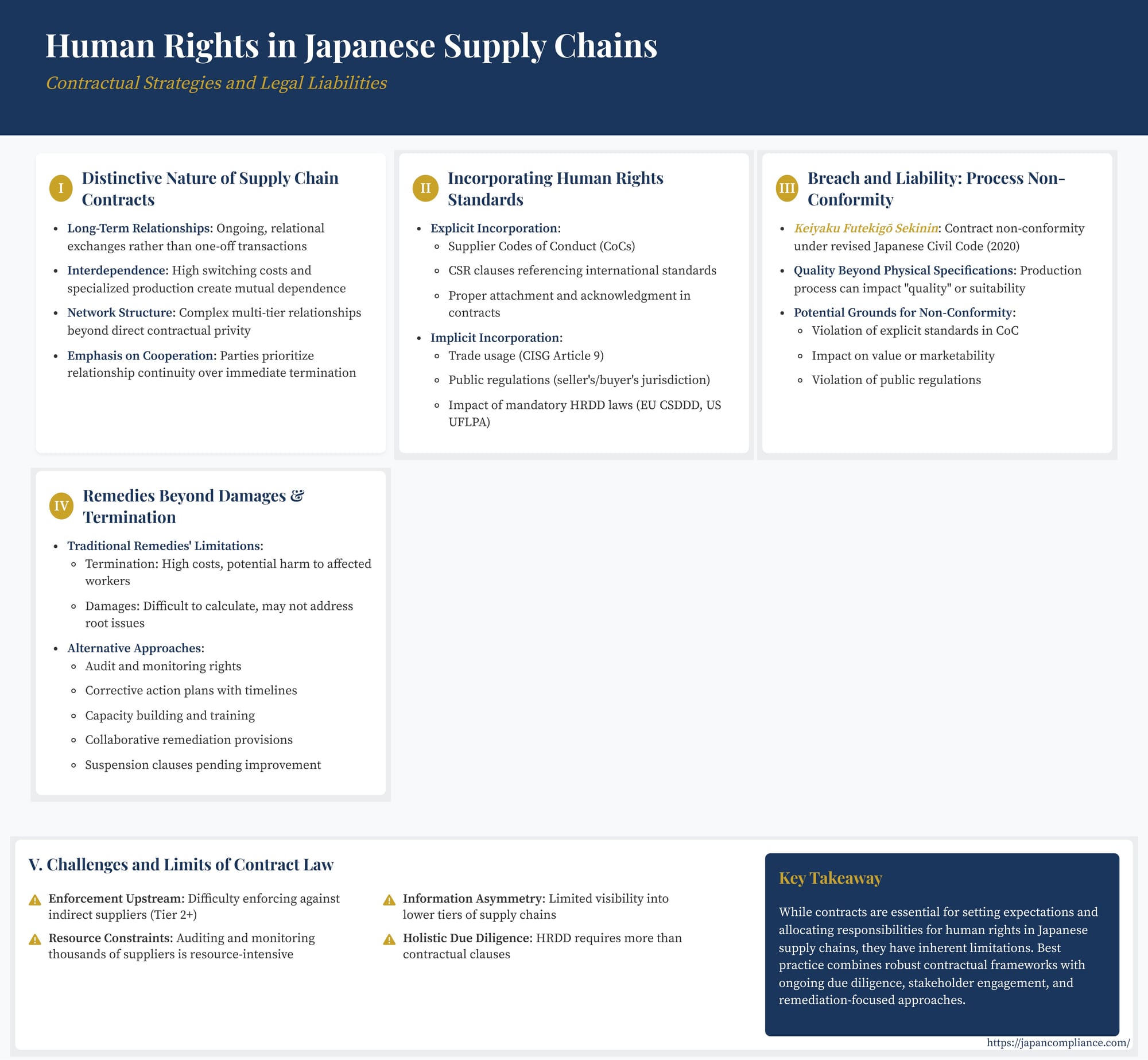

- Japan’s 2022 Guidelines on Respect for Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains move corporate accountability from soft-law rhetoric to practical expectations.

- Embedding clear human-rights clauses, audit rights and cooperative remediation duties into Japanese supply contracts is now standard risk management.

- Under the revised Civil Code (keiyaku futekigō sekinin), goods made with forced or child labour may be deemed non-conforming, giving buyers remedies even when physical specs are met.

- Traditional termination/damages often backfire; contracts should prioritise corrective-action plans, capacity-building and suspension rights.

- Contract law alone is insufficient—robust, ongoing human-rights due diligence (HRDD) across multi-tier supply chains remains essential.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: Contracts in the Era of Human Rights Due Diligence

- The Distinctive Nature of Supply Chain Contracts

- Incorporating Human Rights Standards into Japanese Supply Contracts

- Breach and Liability: The Concept of "Process Non-Conformity"

- Remedies: Beyond Damages and Termination

- Challenges and the Limits of Contract Law

- Conclusion: A Multi-Faceted Approach

Introduction: Contracts in the Era of Human Rights Due Diligence

The global push for corporate accountability regarding human rights is reshaping how businesses manage their supply chains. Following the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) and subsequent OECD guidance, governments worldwide are establishing clearer expectations. Japan's issuance of the "Guidelines on Respect for Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains" in September 2022 underscores this trend, urging all companies operating within its sphere to implement human rights due diligence (HRDD).

While these guidelines are currently soft law, they signal a significant shift in expectations. Companies, including US firms with Japanese operations or suppliers, must now proactively identify, prevent, and mitigate human rights risks not just internally but across their value chains. Contract law inevitably plays a crucial role in this process, serving as the primary legal instrument governing relationships between buyers and suppliers.

However, applying traditional contract law principles to the complex, multi-layered reality of modern supply chains, especially concerning human rights, presents unique challenges. This article explores the evolving role of contracts in managing human rights risks within Japanese supply chains, examining how existing legal concepts might be adapted and where contractual strategies reach their limits, necessitating broader due diligence efforts. We will delve into incorporating human rights standards into agreements, the potential application of Japanese contract non-conformity principles to production processes, and the limitations of traditional remedies in fostering sustainable change.

The Distinctive Nature of Supply Chain Contracts

Before examining specific legal doctrines, it's essential to recognize that supply chain agreements often differ fundamentally from traditional, discrete sales contracts often assumed by classic contract law. Several characteristics are pertinent when considering human rights issues:

- Long-Term Relationships: Supply chains frequently involve ongoing, relational exchanges rather than one-off transactions. Buyers and suppliers often develop long-term partnerships built on mutual trust and repeated interactions, sometimes formalized through framework agreements governing individual purchase orders.

- Interdependence: Participants in a supply chain are often highly interdependent. A supplier might produce specialized components tailored to a specific buyer's final product, making it difficult to switch customers if the relationship ends. Conversely, a buyer (especially a chain leader) invests significantly in qualifying and integrating suppliers and may find it costly and disruptive to find alternatives with comparable technical capabilities, quality standards, and now, human rights performance.

- Network Structure: Supply chains are rarely linear. They involve complex networks with multiple tiers of suppliers, sub-suppliers, service providers, and other actors. A lead company (buyer) may only have direct contractual privity with its Tier 1 suppliers, yet its human rights risks—and responsibilities under HRDD frameworks—extend much further down the chain.

- Emphasis on Cooperation and Continuity: Due to interdependence and the costs of disruption, parties in supply chain relationships often prioritize cooperation and relationship continuity over resorting immediately to termination or litigation when problems arise. This preference influences the types of remedies sought and the effectiveness of contractual enforcement mechanisms.

These characteristics mean that simply applying default contract rules designed for arm's-length market transactions may be insufficient or even counterproductive when addressing nuanced issues like human rights performance deep within a supply chain.

Incorporating Human Rights Standards into Japanese Supply Contracts

A primary strategy for managing human rights risks is embedding expectations directly into supplier agreements. This involves translating the company's human rights policy commitment into enforceable contractual obligations.

1. Explicit Incorporation: Codes of Conduct and CSR Clauses

Many multinational corporations, including those operating in Japan, have developed Supplier Codes of Conduct (CoCs) or specific Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) clauses outlining expectations regarding labor rights, non-discrimination, health and safety, and environmental protection, often referencing international standards like ILO conventions or the UNGPs.

To be legally effective under Japanese contract principles (similar to US contract law), these standards must be properly incorporated into the specific contract with the supplier. Simply publishing a CoC on a company website is generally insufficient. Best practice involves:

- Clearly referencing the CoC within the main body of the supplier agreement.

- Attaching the CoC as an appendix or exhibit to the contract.

- Requiring the supplier's explicit acknowledgment and agreement to comply with the CoC's terms.

- Ensuring the CoC is provided in a language the supplier can reasonably understand.

These clauses often grant the buyer audit rights (though their effectiveness can vary) and stipulate consequences for non-compliance, ranging from requiring corrective action plans to suspension or termination of the contract. Drafting these clauses requires care to ensure they are clear, reasonable, and enforceable under applicable law.

2. Implicit Incorporation: Trade Usage and Public Regulations

Even without explicit contractual clauses, arguments might be made for implicitly incorporating certain human rights standards.

- Trade Usage: Under the UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG), which can apply to international sales involving Japanese parties if chosen or if conflict-of-law rules dictate, parties are bound by usages they have agreed to and by practices established between themselves (Article 9(1)). They are also generally considered bound by usages widely known and regularly observed in the specific trade concerned (Article 9(2)). If certain human rights standards become sufficiently established and consistently observed within a particular industry sector, they could potentially be deemed incorporated as trade usage. However, this is often a high bar to meet.

- Public Regulations: Goods supplied must generally conform to mandatory public regulations in the seller's jurisdiction applicable at the time of contracting. Whether goods must also comply with public regulations in the buyer's jurisdiction or the place of intended resale/use is more complex. Generally, the seller is not responsible for compliance with the buyer's local regulations unless specific circumstances apply: (i) the same regulations exist in the seller's country, (ii) the buyer informed the seller about the specific regulations and relied on the seller's expertise, or (iii) the seller knew or should have known about the regulations due to particular circumstances (e.g., having a branch office there, long-standing trade relations).

With the rise of mandatory HRDD laws (like Germany's Supply Chain Act or the forthcoming EU CSDDD) and import controls based on human rights (like the US UFLPA), the question arises whether compliance with these types of foreign regulations could become an implicit requirement. If a Japanese supplier provides goods to a US buyer, knowing the goods are destined for the US market where UFLPA applies, could the goods be considered non-conforming if produced using forced labor linked to Xinjiang, even without an explicit clause? Legal scholars are actively debating this, but it highlights how external legal pressures can influence contractual expectations.

Breach and Liability: The Concept of "Process Non-Conformity"

A crucial question is what happens when goods are physically compliant with specifications but have been produced in a manner that violates agreed-upon or potentially implicit human rights standards. Can this "process defect" constitute a breach of contract leading to liability?

1. Keiyaku Futekigō Sekinin (Contract Non-Conformity) under the Revised Japanese Civil Code

Japan's Civil Code underwent significant revisions effective April 1, 2020, notably replacing the former framework for "defect liability" (kashi tanpo sekinin) with a concept closer to international norms: "liability for non-conformity" (keiyaku futekigō sekinin). Under Articles 562-564, if the object delivered by the seller does not conform to the contract with regard to kind, quality, or quantity, the buyer has several remedies:

- Demand repair or completion (Article 562).

- Demand substitute performance (Article 562).

- Demand a reduction in price (Article 563).

- Terminate the contract (Article 541, 542).

- Claim damages (Article 415).

The key is whether the delivered item conforms to the "terms of the contract." This conformity is judged based on the explicit and implicit agreements between the parties.

2. Applying Non-Conformity to Production Processes

Legal analysis, particularly drawing parallels with CISG interpretations discussed in Japanese legal commentary, suggests that human rights violations during production could potentially render the goods non-conforming under the keiyaku futekigō sekinin framework, even if the goods themselves meet physical specifications. The argument rests on the idea that the process of production can impact the "quality" or suitability of the goods for their intended purpose, especially if:

- Explicit Standards Were Incorporated: If the contract explicitly required adherence to a CoC prohibiting child labor, delivering goods made with child labor would be a clear non-conformity regarding the agreed "quality" or description of the goods (i.e., goods produced without child labor).

- Impact on Value or Marketability: Goods produced under conditions of severe human rights abuse (e.g., forced labor) may face import restrictions (like UFLPA), become subject to consumer boycotts, or damage the buyer's brand reputation. This negative impact on the goods' economic value, fitness for the buyer's market, or usability could be framed as a lack of conformity with the implied quality or fitness for purpose expected under the contract. Legal scholarship referencing CISG case law (e.g., concerning goods produced in violation of fair trade standards or environmental regulations) supports the notion that production methods can affect conformity if they impact the goods' value or legitimate usability.

- Violation of Public Regulations: If the production process violates mandatory public laws (in the seller's or potentially the buyer's jurisdiction, as discussed above) related to labor or human rights, this could also support a claim of non-conformity.

Therefore, a US buyer receiving goods from a Japanese supplier produced under conditions violating agreed human rights standards might have grounds under Japanese law to claim the goods are non-conforming, triggering the remedies outlined above. This represents a potential avenue for contractual liability beyond physical defects.

Remedies: Beyond Damages and Termination

While the non-conformity framework provides traditional remedies like damages and termination, their effectiveness in the supply chain human rights context is questionable, given the relational nature of these contracts.

- Limitations of Traditional Remedies:

- Termination: Often seen as a last resort due to the high costs of finding and qualifying new suppliers and the potential negative impact on the workers whose rights were violated if the supplier loses business abruptly.

- Damages: Calculating monetary damages for harm caused by "process non-conformity" can be difficult. Furthermore, damages primarily compensate the buyer but may do little to address the underlying human rights issue or provide remedy to affected workers.

- Emphasis on Cooperation and Remediation: The UNGPs and the Japanese Guidelines emphasize remediation and using leverage to improve conditions rather than simply cutting ties. This points towards a need for more cooperative and forward-looking contractual solutions.

- Alternative Approaches: Contracts can be drafted to facilitate collaboration and improvement:

- Audit and Monitoring Rights: Allowing the buyer to assess supplier performance against human rights standards.

- Corrective Action Plans: Requiring suppliers to develop and implement plans to address identified non-compliance within a specific timeframe.

- Capacity Building: Clauses committing the buyer to support supplier improvements through training or other resources.

- Collaborative Remediation: Provisions outlining joint approaches to providing remedy to affected individuals or communities.

- Suspension Clauses: Allowing temporary suspension of orders pending remediation, rather than immediate termination.

The American Bar Association's Model Contract Clauses to Protect Workers in International Supply Chains (Version 2.0), referenced in Japanese legal commentary, reflect this shift, moving away from pure warranty/indemnity approaches towards shared responsibility and emphasizing supplier process improvements and worker remediation. While not directly applicable Japanese law, their principles inform best practices.

- The Challenge of "Preventive" Remedies: Some legal scholars contemplate the desirability of "preventive injunctive relief"—allowing a buyer to compel a supplier during the contract term to rectify non-conforming production processes before significant harm occurs. Under current Japanese (and indeed, most) contract law, obtaining such specific performance related to ongoing production methods, rather than just the delivery of conforming goods, would be highly challenging. It remains more of a theoretical ideal reflecting the preventative goals of HRDD.

Challenges and the Limits of Contract Law

Despite their importance, contractual strategies alone are insufficient to fully address human rights risks in complex supply chains.

- Enforcement Upstream: Enforcing contractual clauses against indirect (Tier 2, 3, etc.) suppliers with whom the buyer has no direct contract is extremely difficult. Flow-down clauses (requiring Tier 1 suppliers to impose similar obligations on their own suppliers) are often used but are hard to monitor and enforce effectively.

- Information Asymmetry: Buyers often lack visibility into the lower tiers of their supply chains, making it difficult to detect violations or monitor compliance even when clauses are in place.

- Resource Constraints: Thoroughly auditing and monitoring potentially thousands of suppliers globally is resource-intensive, especially for SMEs.

- The Need for Holistic Due Diligence: Effective HRDD requires more than just contractual clauses. It involves ongoing risk assessment, stakeholder engagement, capacity building, robust grievance mechanisms, and industry collaboration—elements that go beyond the bilateral contract.

- Interplay with Other Liabilities: Failure to manage supply chain risks effectively, even if not a direct breach of a specific contract clause, could still contribute to reputational damage, operational disruptions, or potentially expose the company and its directors to other forms of liability (tort, regulatory penalties under foreign laws, or breach of director duties if oversight is grossly negligent).

Conclusion: A Multi-Faceted Approach

Contracts are an indispensable tool for setting expectations and allocating responsibilities regarding human rights in Japanese supply chains. The evolution of Japanese contract law, particularly the concept of keiyaku futekigō sekinin (non-conformity), offers potential avenues for holding suppliers accountable for harmful production processes. Incorporating clear human rights standards, audit rights, and provisions for corrective action and remediation into supplier agreements is becoming standard practice.

However, the inherent limitations of contract law—particularly in governing multi-tiered, global supply chains and favoring relationship continuity over punitive measures—mean that contracts cannot be the sole solution. US businesses engaging with Japan must adopt a comprehensive approach. This involves integrating robust, ongoing human rights due diligence processes, as outlined in the 2022 Japanese Guidelines and international standards, alongside carefully crafted contractual strategies. By combining diligent risk management, meaningful stakeholder engagement, and clear contractual frameworks focused on prevention and remediation, companies can more effectively navigate the complex landscape of supply chain human rights responsibility in Japan and beyond.

- Human Rights Due Diligence in Japan: Practical Steps for Supply-Chain Compliance

- Japan's Human-Rights Due-Diligence: Navigating New Expectations for Your Supply Chain

- Beyond Borders: Germany’s Supply-Chain Act & the Rise of Mandatory Human-Rights Due Diligence

- METI Press Release: “Release of Japan's Guidelines on Respecting Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains (English)”

https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2022/0913_001.html - METI Portal: “Business and Human Rights — Towards a Responsible Value Chain”

https://www.meti.go.jp/english/policy/economy/biz_human_rights/index.html