How 'Well-Known' is Well-Known Enough? The Emax Case on Proving Trademark Recognition in Japan

Judgment Date: February 28, 2017

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 27 (Ju) No. 1876 (Main Claim for Injunction, etc. under Unfair Competition Prevention Act; Counterclaim for Injunction, etc. for Trademark Infringement)

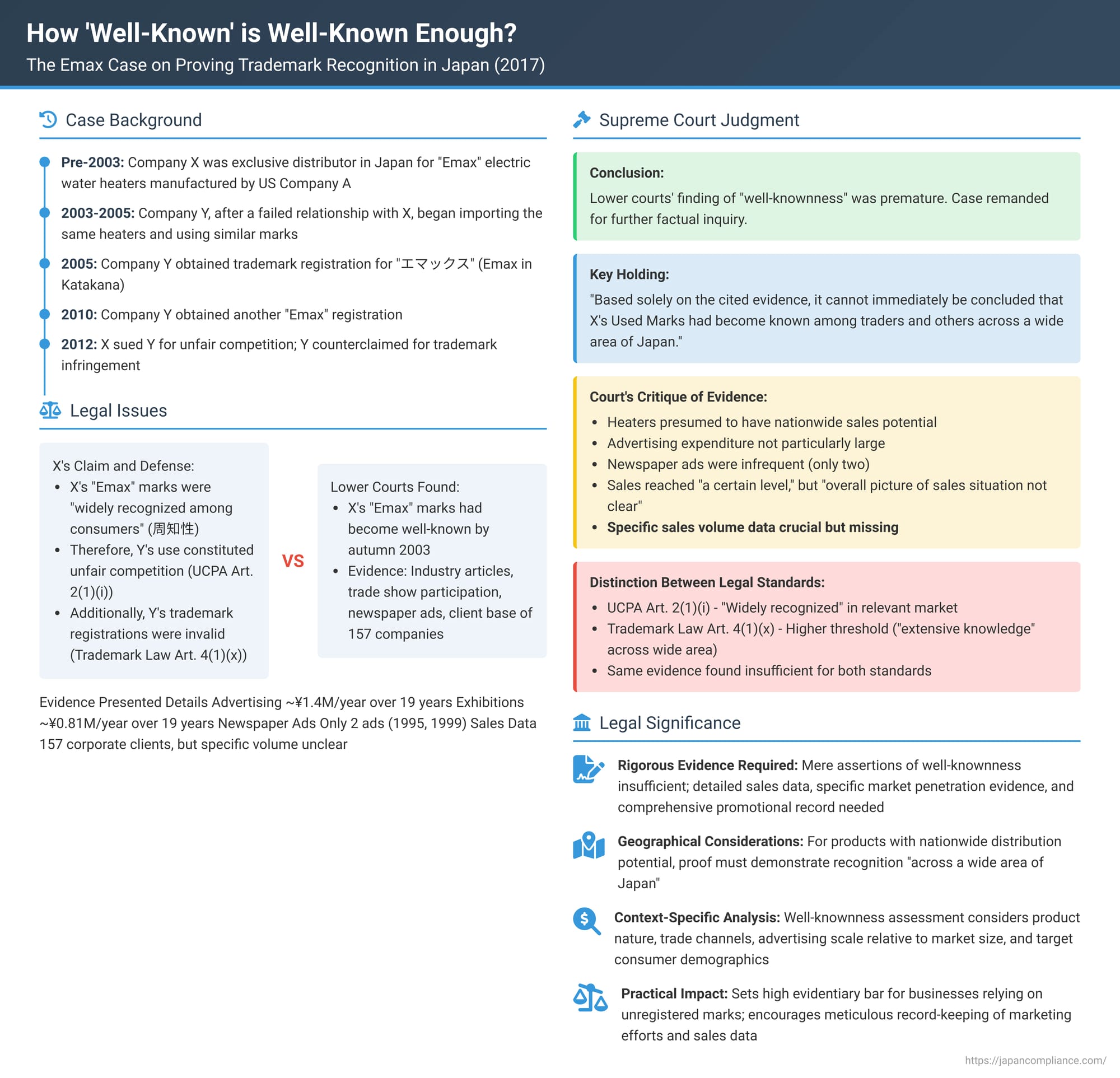

The "Emax" case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2017, offers a significant judicial examination of the evidentiary threshold required to establish that a trademark or service indication is "widely recognized among consumers" (需要者の間に広く認識されている - juyōsha no aida ni hiroku ninshiki sareteiru). This level of recognition, often referred to as "well-knownness" (周知性 - shūchisei), is a critical condition for protection under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1, and similarly for meeting the criteria of Trademark Law Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 10. While the Emax judgment addressed multiple complex legal issues (including time limits for invalidity defenses and the abuse of rights doctrine, covered in a separate analysis of the same judgment under PDF source tm38.pdf), this discussion will focus on the Supreme Court's specific pronouncements and reasoning concerning the proof and degree of well-knownness.

The Emax Dispute Revisited: A Battle Over Brand Recognition

The factual backdrop involved Company X, the exclusive Japanese distributor for electric instant water heaters ("the Heaters") manufactured by a U.S. entity, Company A. Company X marketed these Heaters in Japan using several similar marks, including "エマックス" (Emax in Katakana), "EemaX," and "Eemax" (collectively, "X's Used Marks"). Company Y, after a previous business relationship with Company X concerning these Heaters had ended acrimoniously, began independently importing the same Heaters from Company A and selling them in Japan, also using marks identical or very similar to X's Used Marks. Furthermore, Company Y successfully obtained Japanese trademark registrations for "Emax" and a related mark for electric water heaters ("Y's Registered Marks").

This led to litigation. Company X filed a main claim against Company Y, asserting that Y's use of identical marks on the same goods constituted unfair competition under UCPA Article 2(1)(i). A key element for this claim was establishing that X's Used Marks were "widely recognized among consumers" as indicating X's business or goods. In response, Company Y filed a counterclaim for trademark infringement based on its own Y's Registered Marks. To this counterclaim, Company X defended by arguing that Y's Registered Marks were invalid under Trademark Law Article 4(1)(x), because at the time Y applied for its marks, X's Used Marks were already well-known and Y's marks would cause confusion. This defense, too, hinged on proving the well-knownness of X's Used Marks.

Lower Courts' Finding of Well-Knownness for "Emax"

Both the Oita District Court and the Fukuoka High Court (on appeal) found in favor of Company X on the issue of well-knownness. They concluded that X's Used Marks had indeed become "widely recognized among consumers" as indicating X's business in relation to the Heaters, at least by the autumn of 2003 (when Company Y's representative had initiated distributorship negotiations with Company X, thereby demonstrating awareness).

The evidence upon which the lower courts based this finding included:

- Several articles in industry newspapers (e.g., construction, distribution, fisheries economics) from 1994, announcing Company X's exclusive distributorship agreement with Company A for the Heaters, some including photos of the product.

- Company X's participation in trade shows in Tokyo (1996, 1998) and Kobe (1995) to promote the Heaters, with the Kobe exhibition being reported in an industrial technology newspaper.

- Newspaper advertisements placed by Company X for the Heaters, specifically one in the Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun (July 1995) and another in the Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun (March 1999).

- Company X's advertising and promotion expenses, which totaled approximately JPY 26.74 million for advertising and JPY 15.51 million for exhibitions over the period from FY1994 to FY2012 (roughly 19 years). This averaged to about JPY 1.4 million per year for advertising and JPY 0.81 million per year for exhibitions.

- Company X's sales record, indicating that by July 2000, its clientele for the Heaters included 157 corporate entities, such as construction companies, food manufacturers, trading companies, and hotels, with the number of clients reportedly increasing thereafter. However, specific details regarding the duration of sales to these clients and the total number of units sold were noted as unclear.

- An internal newsletter from one of Company X's major corporate clients (Company B's purchasing department) dated July 1995, which introduced the Heaters, highlighted their excellent performance, and mentioned that over 1,000 units had already been installed in locations like condominiums and hospitals.

- The fact that Company Y's own representative, prior to Y's incorporation and despite no prior personal or capital ties to Company X, had learned about the existence of the Heaters through an acquaintance and subsequently approached Company X to negotiate a sales agency agreement.

The Supreme Court's Stricter Scrutiny of "Well-Knownness"

The Supreme Court took a more critical view of the evidence and overturned the High Court's finding that X's Used Marks were "widely recognized" for the purposes of both the UCPA and the Trademark Law claims. It concluded that the facts established by the High Court were insufficient to immediately lead to such a conclusion.

I. For the Unfair Competition Claim (UCPA Art. 2(1)(i))

The Court reasoned:

- Nature of Goods and Sales Area: The Heaters, by their nature and the observed trade realities, were not products whose sales would likely be confined to a limited geographical area; their potential sales area was presumed to be nationwide.

- Evaluation of X's Promotional Activities:

- While there were introductory articles in several industry-specific newspapers and participation in trade shows, direct newspaper advertisements placed by Company X as the advertiser were infrequent (only twice, in 1995 and 1999).

- The total expenditure on advertising and exhibitions, when spread over nearly two decades and considered in the context of a presumed nationwide sales area, was not deemed to be a particularly large sum.

- Evaluation of X's Sales Performance:

- The Court acknowledged sales to a "considerable number of corporate entities," including major construction companies, and that sales volume had reached "a certain level or more".

- However, it emphasized that the "overall picture of the sales situation, such as specific sales volume, was not clear".

- Significance of Y's Representative's Knowledge: The fact that Company Y's representative learned about the Heaters through an acquaintance and initiated negotiations with Company X was considered, but even in conjunction with the other evidence, the Court found these circumstances insufficient to "immediately conclude that X's Used Marks had become known among traders and others across a wide area of Japan".

- Conclusion for UCPA: The Supreme Court held that the High Court had erred in law by finding X's Used Marks "widely recognized" under UCPA Art. 2(1)(i) based solely on the cited evidence, without a more thorough examination of Company X's "concrete sales situation, etc.". This part of the judgment was remanded for further factual inquiry.

II. For the Trademark Law Defense (Art. 4(1)(x))

Regarding Company X's defense to Y's trademark infringement counterclaim (which relied on X's marks being well-known under Trademark Law Art. 4(1)(x) prior to Y's registrations), the Supreme Court applied the same critical assessment of X's advertising and sales activities. It concluded that, based on this evidence, it could "not immediately be said" that X's Used Marks had become known among traders and others across a wide area of Japan by the time Company Y had applied for its various trademark registrations. Consequently, the High Court's finding of well-knownness for the purpose of Trademark Law Art. 4(1)(x) was also deemed to be based on insufficient factual inquiry and an error of law, leading to this part of the case also being remanded.

Defining "Widely Recognized Among Consumers" – Legal Standards and Practical Challenges

The Supreme Court's judgment in Emax, while focused on the specific facts, provides important practical lessons on the evidentiary burden for establishing "well-knownness." The accompanying PDF commentary offers further context.

- Well-Knownness (周知性 - shūchisei) under UCPA Art. 2(1)(i):

- This provision aims to protect users of unregistered indications of source that have achieved a certain level of market recognition, thereby preventing others from causing confusion as to business origin.

- The term "widely recognized" is assessed based on the actual trade situation for the specific goods or services. The core question is whether the indication is widely recognized among the consumers of the alleged infringer (the defendant) within their sales territory. It's not strictly necessary to prove nationwide fame if the defendant's activities are localized, though the Emax case dealt with a product presumed to have nationwide distribution.

- "Consumers" in this context includes not just end-users but also traders at various stages of the distribution chain (e.g., wholesalers, retailers).

- The degree of recognition for UCPA Art. 2(1)(i) is generally considered less stringent than that required for "famous" indications under UCPA Art. 2(1)(ii) (which protects against dilution). The focus for Art. 2(1)(i) is whether the indication has developed sufficient goodwill to warrant protection against source confusion and whether allowing another's imitation would offend principles of good faith and fair dealing in trade.

- Exceptional Cases for Proving Well-Knownness: Professor Tamura's categorization (as cited in the PDF commentary) suggests that while distinctiveness used in business often leads to a corresponding scope of well-knownness, certain situations demand stronger proof:

- Non-Distinctive Indications: If the indication is common for the type of goods, or is a product container or shape not inherently intended as a source identifier, special circumstances are needed to show it has acquired distinctiveness and become well-known as such.

- Geographical Disparity: If the defendant's business is widespread or operates in areas remote from the plaintiff's primary area of operation, the plaintiff needs specific evidence that their mark's recognition extends into the defendant's territory.

- Thinly Spread Nationwide Sales: If a plaintiff's sales are spread thinly across a wide national area without achieving a significant concentration or threshold of well-knownness in any particular region, they may be forced to argue for nationwide well-knownness. If this high bar isn't met, the claim can fail (as seen in cases like STEFANO RICCI and Bio Selysin).

The PDF commentary posits that the Emax case likely falls into this third category of "thinly spread sales". Thus, the Supreme Court's demand for more robust proof of nationwide recognition should be understood in this context, rather than as a universal requirement for all UCPA Art. 2(1)(i) cases.

- Critique of the Supreme Court's Focus in Emax: One scholarly criticism highlighted in the PDF commentary is that the Supreme Court's analysis of well-knownness predominantly focused on Company X's (the plaintiff's) own nationwide activities and efforts. Arguably, the more pertinent inquiry for UCPA Art. 2(1)(i) should be the level of recognition of X's marks among Company Y's (the defendant's) actual or potential customers in Y's specific sales areas.

- Well-Knownness under Trademark Law Art. 4(1)(x):

- This provision, which prevents the registration of a trademark that is identical or similar to another person's well-known trademark and likely to cause confusion, also uses the standard "widely recognized among consumers".

- The degree of recognition required for Trademark Law Art. 4(1)(x) is generally understood to be higher or more extensive than that for UCPA Art. 2(1)(i). While not necessarily demanding nationwide fame in every instance, recognition merely within a single prefecture is usually insufficient; it typically requires recognition across a "considerably wide area," such as several prefectures or a major economic region (e.g., the Kansai area). Some scholars refer to this as requiring "extensive knowledge" (広知性 - kōchisei).

- Given this higher threshold, the Supreme Court's finding that the evidence was insufficient to immediately establish well-knownness for the UCPA claim logically extended to its finding that well-knownness was also not immediately established for the Trademark Law Art. 4(1)(x) defense.

Practical Takeaways for Businesses

The Supreme Court's detailed scrutiny of the evidence in the Emax case offers important lessons for businesses seeking to establish or rely on the "well-known" status of their marks in Japan:

- Meticulous Record-Keeping is Crucial: Companies must maintain thorough and detailed records of their sales (volume, geographical distribution, customer types), advertising and promotional activities (expenditure, reach, frequency, types of media used), participation in trade shows, media coverage, and any other evidence that can demonstrate market presence and consumer awareness.

- Demonstrating Nationwide Recognition is Challenging: Proving that a mark is "widely recognized" across the entirety of Japan is a significant evidentiary burden, especially for products that are not mass-marketed directly to general end-consumers or that have diffuse B2B sales channels. Modest advertising budgets and sales to a limited number of corporate clients, even if those clients are large, may not suffice without further concrete evidence of broad market penetration and awareness.

- Context Matters: The nature of the product, the relevant consumer base (e.g., specialized industry professionals vs. general public), and the geographical scope of the dispute will all influence the type and quantum of evidence needed.

- Interplay of UCPA and Trademark Law Standards: While both statutes use similar terminology ("widely recognized among consumers"), the practical evidentiary threshold for Trademark Law Art. 4(1)(x) is often considered higher than for UCPA Art. 2(1)(i). Success in one does not guarantee success in the other, though failure to meet the UCPA standard will likely mean failure to meet the trademark law standard.

Conclusion

The Emax Supreme Court judgment, particularly its detailed examination of the factual basis for "well-knownness," serves as a significant judicial benchmark and a cautionary tale. It underscores that merely conducting business and undertaking some level of advertising and sales does not automatically equate to a mark being "widely recognized among consumers" for the purposes of either the Unfair Competition Prevention Act or the Trademark Law, especially when nationwide recognition is claimed or implicated by the nature of the product's distribution. The Court's decision to remand the case for a more thorough examination of concrete sales data and market penetration highlights the need for robust, specific, and persuasive evidence to meet this critical legal standard. Businesses aiming to rely on the well-known status of their marks must be prepared to substantiate their claims with comprehensive proof of their mark's actual impact and recognition in the relevant Japanese market.