How to Steal Your Own Money: A Japanese Ruling on Fraud and Mistaken Bank Transfers

Imagine checking your bank account and discovering that a large sum of money has been deposited by mistake. You know it's not yours, but it's sitting in your account. Under the principles of banking law, the funds are now legally part of your account balance, and you have a right to withdraw them. If you go to the bank and take out the cash without saying a word about the error, have you committed a crime? Can you be guilty of stealing what is, in a civil law sense, your own money?

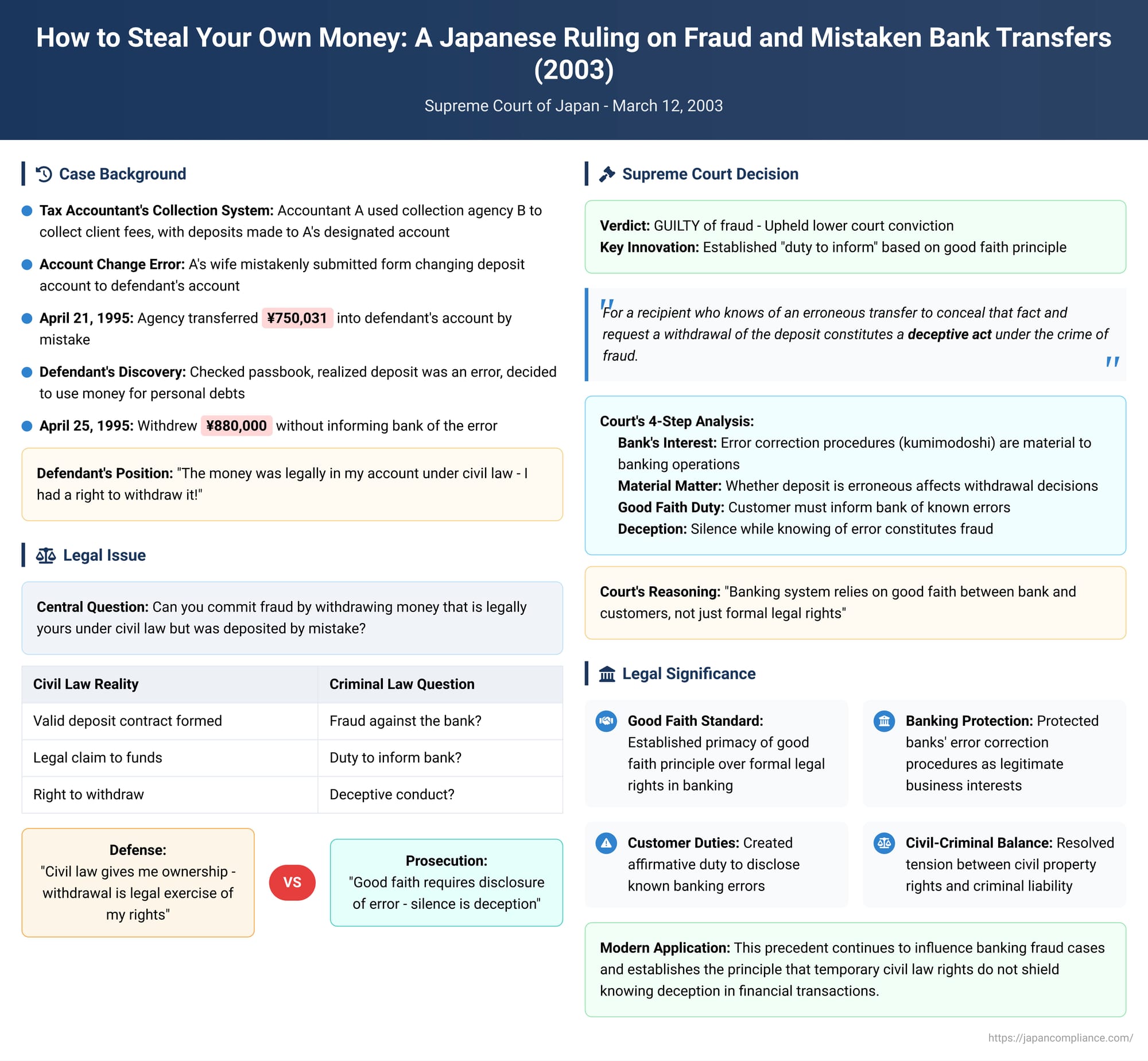

This perplexing legal and ethical question was the subject of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 12, 2003. The Court's surprising answer was a definitive "yes." In a ruling that has had profound implications for banking transactions, the Court found that knowingly withdrawing mistakenly deposited funds constitutes fraud against the bank. The decision hinges on the creation of a "duty to inform" based on the principle of good faith.

The Civil Law Paradox: You Own the Money, But Can You Take It?

To understand the complexity of the case, one must first grasp the civil law reality of a bank transfer. The Supreme Court began its own analysis by reaffirming a 1996 civil law precedent: when money is transferred into a recipient's bank account, even by mistake, a valid deposit contract is formed between the recipient and their bank. The recipient legally acquires a claim (a right to be paid) against the bank for the amount deposited.

This creates a paradox at the heart of the case: If the defendant legally has a claim to the funds in his account, how can withdrawing them be a crime against the bank?

The Facts of the Case: The Accountant's Mistake

The case began with a simple clerical error. A tax accountant, A, used a collection agency, B, to collect fees from his clients. The agency would collect the fees and deposit them in a lump sum into A's designated bank account. However, A's wife mistakenly submitted a form to the agency that changed the designated deposit account to one belonging to the defendant.

Following these erroneous instructions, on April 21, 1995, the collection agency transferred 750,031 yen into the defendant's account. The defendant, upon checking his passbook, noticed the unexpected deposit and realized it was a mistake. Seeing an opportunity, he decided to use the money to pay off his own personal debts.

On April 25, he went to the bank branch. Without telling the bank teller that a significant portion of his balance was due to an erroneous transfer, he requested a withdrawal of 880,000 yen. The teller, unaware of the situation, processed the request and gave him the cash.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Reasoning: A "Duty to Inform"

The lower courts convicted the defendant of fraud, and the Supreme Court upheld the conviction. Its reasoning, however, did not challenge the civil law reality. Instead, it built a novel argument based on the bank's operational interests and the customer's duty of good faith. The Court's logic proceeded in four key steps.

Step 1: The Bank's Interest in Correcting Errors. The Court first detailed standard banking practices. It noted that when a sender reports an erroneous transfer, banks have a procedure known as "reversal" (kumimodoshi). Through this process, the bank can, with the recipient's consent, reverse the transaction and return the funds to the sender. These procedures, the Court found, are not just internal matters; they are beneficial for maintaining a safe and reliable payment system and are necessary to prevent the bank from being drawn into disputes between the sender and the recipient.

Step 2: The "Material Matter." Because these important error-correction procedures exist, the Court ruled that whether a deposit is the result of a mistake is a "material matter" for the bank when it decides whether to approve a withdrawal request.

Step 3: The Customer's "Duty of Good Faith." The Court then turned its focus to the recipient. It held that this "materiality" gives rise to a special duty for the account holder. The Court stated that an account holder in a continuous banking relationship, upon learning of an erroneous transfer, has a "duty under the principle of good faith" (shingi-soku-jō no gimu) to inform the bank of the error. This allows the bank to take its corrective measures. The Court added that this duty is also a matter of "social common sense," since the recipient has no substantive right to keep the money and is obligated to return it to the sender.

Step 4: The Deception by Omission. With this duty established, the final step was simple. The Court concluded:

"Therefore, for a recipient who knows of an erroneous transfer to conceal that fact and request a withdrawal of the deposit constitutes a deceptive act under the crime of fraud."

The teller, unaware of the true nature of the funds, is the deceived party who is induced by this deception (the silence) to make the payment. This completes all the elements of fraud.

Analysis and Critique: A "Precarious" Foundation?

The Supreme Court's ruling is a clever piece of legal reasoning that navigates the conflict between civil property rights and criminal liability. However, legal commentators have pointed out that its foundation is potentially precarious.

The core critique focuses on the nature of the bank's "protectable interest." The bank's ability to perform a kumimodoshi is not a formal legal right enshrined in statute; it is an internal banking practice that, crucially, requires the consent of the recipient to execute. Critics argue that such a weak, conditional interest may not be a strong enough foundation upon which to build a criminal fraud conviction. This is contrasted with modern laws targeting phishing scams, where banks have a clear statutory duty to assist victims, giving them a much stronger and legally defined interest in the funds.

Alternative legal theories exist. One, the "abuse of right" theory, argues that while the defendant has a civil right to the funds, exercising it in this context is an abuse of that right. However, the Supreme Court chose not to rely on this abstract concept, focusing instead on the concrete procedures of the bank and the customer's duty of good faith. Another view, which the Court rejected, would be to simply separate civil and criminal law entirely and declare the deposit criminally invalid even if it is civilly valid. The Court's approach attempts to respect the civil law finding while still establishing criminal liability.

Conclusion: The Primacy of Good Faith in Banking

The 2003 Supreme Court decision on erroneous bank transfers is a landmark ruling that carves out a specific duty for bank customers. It definitively establishes that knowingly withdrawing funds that have been mistakenly deposited into your account is not a lucky windfall—it is fraud against the bank.

The core principle is that the banking system relies on more than just formal legal rights; it relies on a fundamental duty of good faith between the bank and its customers. While an individual may have a temporary civil law claim to mistaken funds in their account, they have a superseding ethical and legal duty to inform the bank of the error. Choosing to remain silent and withdraw the money is an act of deception that turns a legal paradox into a criminal act. The ruling, while theoretically debatable, sends a powerful message about the importance of honesty and integrity in financial transactions.