How to Forge a Document Without Lying About the Author's Name: Japan's 'Fake IDP' Case

Imagine a private company begins printing and selling documents that are nearly identical in appearance to an official government-issued credential, like a passport or a driver's license. Now, imagine you are an employee of that company, and you have the company's full permission to create these documents in its name. Since you have authorization from the named author (the company), can you be guilty of the crime of document forgery? Or does the act of creating a document that mimics an official credential, but which lacks any actual legal authority, constitute a more sophisticated form of forgery?

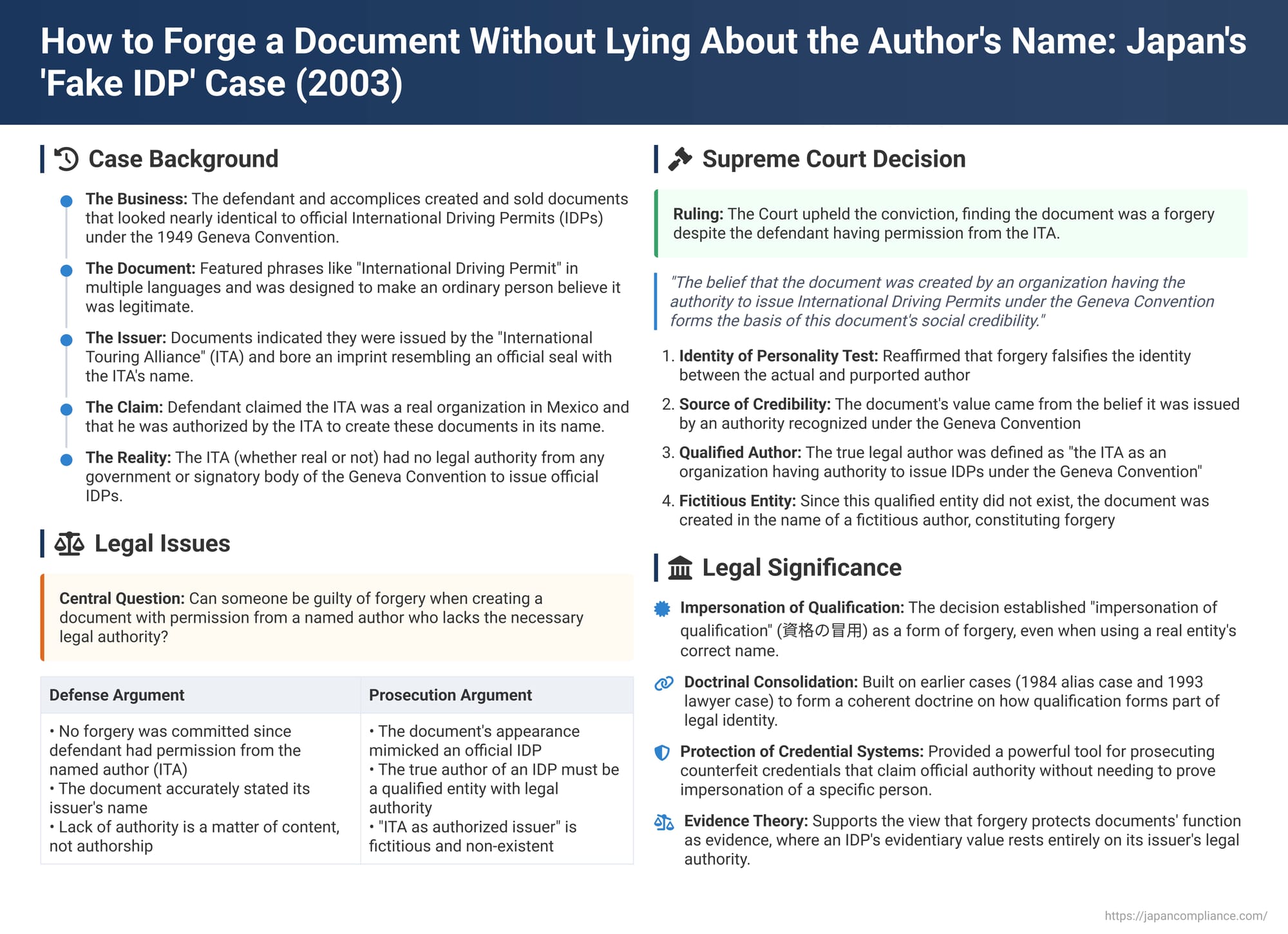

This question of "impersonating a qualification" was at the heart of a landmark October 6, 2003, decision by the Supreme Court of Japan. The case, involving fake International Driving Permits, clarified how the law defines a document's "author" when its entire value and social credibility are built on a false claim to legal authority.

The Facts: The "International Driving Permit" from a Private Group

The case centered on the defendant and his accomplices, who were in the business of creating and selling documents to customers that looked remarkably like official International Driving Permits (IDPs).

- The Document: The documents they created were designed to be nearly indistinguishable from genuine IDPs issued under the 1949 Geneva Convention on Road Traffic, a treaty to which Japan is a signatory. The cover featured phrases like "International Driving Permit" in English and French and was designed to make any ordinary person believe it was a legitimate credential.

- The Purported Issuer: The document indicated that it was issued by an organization named the "International Touring Alliance" (ITA), and it bore an imprint resembling an official seal with the ITA's name.

- The Defendant's Defense: The defendant's core argument was that he was not a forger because he had permission from the document's named author. He claimed that the ITA was a real, existing private organization in Mexico and that he was duly authorized by the ITA to create these documents in its name. (For the purpose of the legal analysis, the courts could not definitively prove that the ITA did not exist).

- The Crucial Missing Element: However, it was undisputed that the ITA, whether real or not, had no legal authority from any government or signatory body of the Geneva Convention to issue official IDPs. The defendant was fully aware of this complete lack of legal authority.

The Legal Question: Can You Forge a Document in the Name of a Real Entity That Gave You Permission?

The defendant's argument presented a legal paradox. The crime of forgery is typically understood as creating a document in another's name without permission. Here, the defendant claimed to have permission from the named author, the ITA. The lower courts, however, convicted him of forgery. They reasoned that the legal author of a document like this is not just the named entity, but the entity in its capacity as a qualified issuer. Since "ITA, the authorized issuer of IDPs" did not exist, the document was a forgery in the name of a fictitious entity. The defendant appealed this logic to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Authority is the Bedrock of Identity

The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, providing a clear and powerful analysis that built upon its previous rulings on forgery. The Court's reasoning proceeded in several key steps:

- Start with the "Identity of Personality" Test: The Court began by reaffirming the established legal principle that the essence of forgery is to falsify the "identity of personality" between the author of a document and the person or entity named in it. This principle had been established in earlier landmark cases, including a 1984 case on using an alias and a 1993 case on impersonating a professional with the same name.

- Identify the Source of "Social Credibility": The Court then asked a critical question: what gives this specific document its social trust and value? It concluded that the belief that the document was created by an "organization having the authority to issue International Driving Permits under the Geneva Convention" is precisely what "forms the basis of this document's social credibility."

- Define the "Qualified Author": Therefore, the true legal "author" (meigi-nin) of this document is not the simple entity "International Touring Alliance." The author is the qualified entity: "the International Touring Alliance, as an organization having the authority to issue International Driving Permits under the Geneva Convention."

- A Fictitious Author = Forgery: Since the real ITA (even assuming it existed) possessed no such legal authority, this "qualified author" was a non-existent, fictitious entity (kyomu-jin). The defendant's act was therefore the creation of a document in the name of this fictitious, qualified author. This is a classic case of faking the author's identity, which constitutes forgery. The permission from the real, but unqualified, ITA was legally irrelevant to this charge.

Analysis: The Impersonation of Qualification

This decision is the Supreme Court's clearest articulation of the legal principle of "impersonation of qualification" (shikaku no bōyō) as a form of forgery. The ruling is a sophisticated application of the idea that a document's author is defined not just by a name, but by the attributes that give that name authority and meaning in a specific context.

- Building on Precedent: The decision is logically consistent with earlier key rulings. In the 1984 "alias" case, the Court found that a re-entry permit application required the author to have the attribute of "legal residence status." In the 1993 "fake lawyer" case, it found that a legal invoice required the author to have the attribute of "being a licensed lawyer." This 2003 case solidified the underlying principle: the attributes that form the basis of a document's social credibility are an inseparable part of its author's legal identity.

- The "Responsibility" and "Evidence" Theories: The Court's logic aligns with prominent legal theories. From the perspective of the "responsibility theory," a person who receives a document like an IDP holds the issuing authority responsible for its validity; that authority is thus the author. From the perspective of forgery as a crime against a document's function as evidence, the credibility of an IDP as evidence rests entirely on the legal authority of its issuer. A document created by an unauthorized body has no such evidentiary value, and creating it harms the public's trust in this entire class of documents.

Conclusion

The 2003 "fake IDP" case is a powerful tool for prosecuting the creation of counterfeit credentials and other documents whose value is derived from a false claim to official authority. It establishes the critical principle that when a document's social credibility is inextricably linked to a specific legal authority or qualification, the legal "author" of that document is defined as the entity that possesses that qualification. Creating a document that impersonates this "qualified author" constitutes forgery, even if one has permission from a real but unqualified entity that shares the same name. The ruling affirms that Japanese law protects the public's trust not just in names, but in the legal authority and qualifications that those names are meant to represent.