How Much Re-Investigation on Remand? Japan Supreme Court Limits Scope in Juvenile Case (July 11, 2008 Decision)

Appellate courts serve the crucial function of reviewing lower court decisions for errors. When an error is found that may have affected the outcome, the appellate court often remands the case – sends it back – to the lower court for reconsideration or further proceedings consistent with the appellate ruling. In Japan's juvenile justice system, this process applies when the High Court reviews decisions of the Family Court.

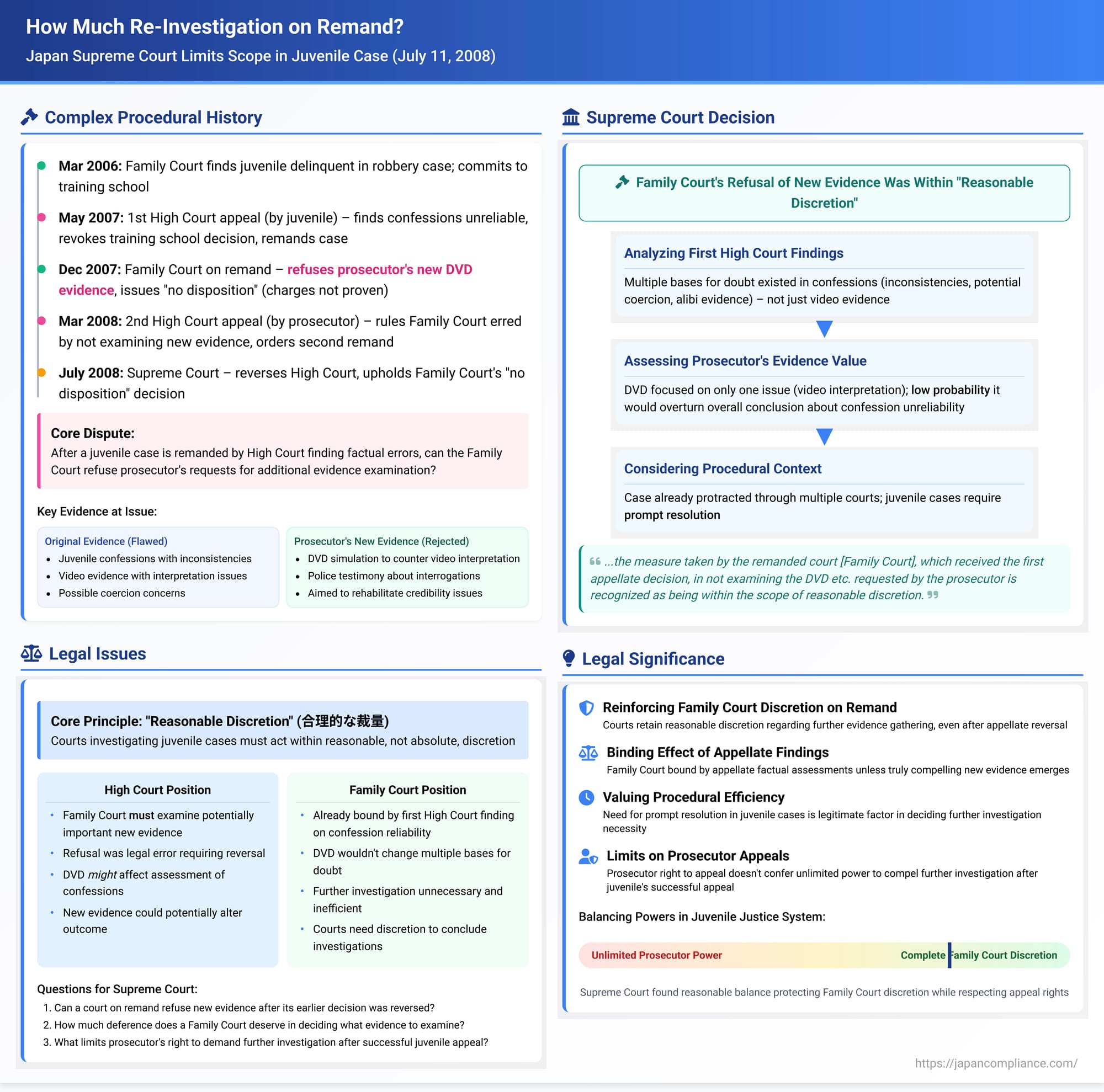

A key principle governing these proceedings is that both the Family Court and the High Court, when investigating facts, operate not under absolute freedom but within the bounds of "reasonable discretion" (gōriteki na sairyō), guided by the Juvenile Act and procedural fairness. But what happens when a case cycles through this process multiple times? If the High Court finds factual errors, remands the case, and the Family Court then reaches a conclusion based on that remand (perhaps finding no delinquency), can the prosecutor appeal again? And if the High Court accepts the second appeal, how much power does it have to compel or conduct further factual investigation, potentially second-guessing the Family Court's handling of the case after the first remand? This complex interplay of appellate review, lower court discretion on remand, and the specific procedures for prosecutor appeals in juvenile cases was the focus of a Supreme Court of Japan decision issued on July 11, 2008. This case involved the same underlying facts as the previously discussed 2005 decision (Heisei 17 (Shi) No. 23), but dealt with the second time the case reached the High Court and subsequently the Supreme Court.

Case Background Revisited: Remand, Refusal to Investigate, Second Appeal Cycle

To briefly recap the essential procedural history leading to this specific ruling:

- Initial Family Court (1st Jiken): Found Juvenile J delinquent in a group robbery causing injury and committed J to a juvenile training school (March 2006). This finding relied heavily on confessions from J and co-accused juveniles C and D.

- 1st High Court Appeal (by J): Found the confessions unreliable due to multiple inconsistencies, potential coercion, and conflicting evidence (including alibi evidence for D and issues with video evidence regarding adult co-conspirator B). Declared a "suspicion of significant factual error," revoked the training school decision, and remanded the case to Family Court (May 2007). Crucially, this decision questioned the existing evidence base but did not explicitly order further specific investigations.

- Family Court on Remand (2nd Jiken): The prosecutor participated. The prosecutor requested the court examine new evidence intended to rehabilitate the credibility issues identified by the High Court: specifically, a DVD simulation attempting to counter the High Court's interpretation of the video evidence regarding co-conspirator B's physique, and testimony from police officers involved in the initial interrogations. The Family Court refused to examine this new evidence, deeming it unnecessary. Feeling bound by the High Court's strong negative assessment of the original confessions, the Family Court concluded the delinquent act was not proven and issued a "no disposition" decision (fushobun kettei) (December 2007).

- 2nd High Court Appeal (by Prosecutor): The prosecutor appealed again, this time challenging the "no disposition" decision. The grounds were twofold: significant factual error (arguing delinquency was proven) and, importantly, a violation of law affecting the decision – specifically, that the Family Court on remand erred by refusing to examine the prosecutor's proffered new evidence (the DVD and police witnesses). The High Court accepted the appeal. It reasoned that examining the DVD could potentially alter the assessment of B's involvement (a key point in the first High Court decision), which in turn might lead to a different conclusion about the confessions' credibility after potentially hearing from the police officers. Therefore, the High Court concluded, the Family Court's refusal to conduct this further investigation was a legal error justifying reversal. It revoked the "no disposition" decision and remanded the case back to the Family Court again (March 2008).

- Re-appeal to Supreme Court (by J): J's attendant lawyer filed a re-appeal against this second High Court remand decision, arguing it improperly interfered with the Family Court's reasonable discretion on remand.

The Legal Standoff: Discretion on Remand vs. Appellate Oversight

The core issue for the Supreme Court was the extent of the Family Court's discretion after receiving a case back on remand with strong indications from the appellate court that the original factual findings were unreliable. Did the Family Court have the discretion to decide that further investigation, even if offered by the prosecutor, was unnecessary or unlikely to change the outcome dictated by the appellate court's prior ruling? Or was the High Court correct in its second decision, essentially finding that the Family Court had a duty to examine the new evidence before finalizing its decision on remand?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Family Court's Discretion Was Reasonable

The Supreme Court sided with the juvenile, reversing the second High Court decision and reinstating the Family Court's "no disposition" order.

Scope of Discretion on Remand:

The Court reiterated the established principles: both the Family Court's initial evidence gathering and the High Court's factual investigation on appeal are governed by "reasonable discretion." The critical question was whether the Family Court's exercise of discretion on remand in this instance was reasonable.

Analyzing the Need for the Prosecutor's New Evidence:

The Supreme Court carefully reviewed the reasoning of the first High Court decision. It emphasized that the first remand was based on findings that cast doubt on the core confessions due to multiple factors – not just the interpretation of the video regarding suspect B, but also D's potential alibi, inconsistencies between confessions, and potential issues with how the confessions were obtained.

Given these multiple grounds for doubt established by the first High Court decision, the Supreme Court concluded that the second High Court decision was incorrect in finding a "high probability" (gaizensei ga takaku) that examining the prosecutor's new DVD evidence (focused mainly on the video interpretation issue) would actually overturn the first High Court's overall conclusion about the unreliability of the confessions. The Court stated, "...it cannot be recognized that there was a probability that the conclusion of the first appellate decision would be overturned by examining the DVD etc. in this case."

Considering Procedural History and Speedy Resolution:

Furthermore, the Supreme Court explicitly took into account the "procedural history of this case" (already protracted through multiple court levels) and the "characteristic of juvenile protection cases requiring early and prompt processing." These factors weighed in favor of respecting the Family Court's decision on remand to conclude the case based on the existing record as assessed by the first High Court decision, rather than embarking on potentially lengthy further investigations offered by the prosecutor.

Conclusion on Discretion and Binding Effect:

Therefore, the Supreme Court held:

"...the measure taken by the remanded court [Family Court], which received the first appellate decision, in not examining the DVD etc. requested by the prosecutor is recognized as being within the scope of reasonable discretion."

Since the Family Court acted reasonably in deciding not to examine new evidence, it remained bound by the first High Court decision's negative assessment of the original evidence (citing the Hakkai precedent on the binding effect of remand decisions). Consequently, its "no disposition" decision based on finding no delinquency proven was legally sound and free from factual error based on the evidence properly before it.

The second High Court decision, which found legal error in the Family Court's refusal to examine the new evidence and ordered another remand, was itself flawed by misjudging the scope of the Family Court's reasonable discretion and the binding nature of the first remand decision. The Supreme Court found this error serious enough to warrant reversal ex officio to prevent a grave injustice.

Significance: Protecting Finality and Discretion After Remand

This 2008 decision provides important clarification on the dynamics of juvenile appeals, especially in the context of the prosecutor appeal system. Its key implications include:

- Reinforcing Family Court Discretion on Remand: It confirms that even after an appellate court finds errors and remands, the Family Court retains reasonable discretion regarding whether further evidence gathering is necessary, particularly concerning evidence offered by the party who lost the initial appeal.

- Weight of Prior Appellate Findings: It underscores the binding effect of an appellate court's factual assessments on the lower court upon remand, unless significant new evidence mandating reconsideration emerges (which the Supreme Court found the prosecutor's DVD did not).

- Importance of Prompt Resolution: It explicitly recognizes the need for speedy case processing in juvenile matters as a factor influencing the reasonableness of procedural decisions, potentially limiting cycles of appeal and remand based on offers of supplementary evidence.

- Limits on Prosecutor Appeals: While affirming the prosecutor's right to appeal under Article 32-4, the decision suggests this does not grant the prosecutor an unlimited right to compel further investigation on remand if the Family Court reasonably deems it unnecessary in light of prior appellate findings.

The supplementary opinion by Justice Tahara further bolsters the outcome by providing a detailed factual analysis highlighting the significant weaknesses in the confessions and the strength of the alibi evidence, serving as a cautionary tale about the risks of false confessions, particularly in juvenile cases involving group dynamics and investigative pressure.

In essence, this ruling establishes that while appellate courts can review Family Court decisions for factual errors and even conduct their own investigations within reason, they must also respect the Family Court's reasonable discretion when managing remanded proceedings, especially when deciding whether further investigation is truly warranted in light of prior appellate findings and the need for timely resolution in juvenile justice.