How Much is Too Much? Director's Business Judgment in Share Buyouts Under Japanese Law

Case: Action for Damages

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of July 15, 2010

Case Number: (Ju) No. 183 of 2009

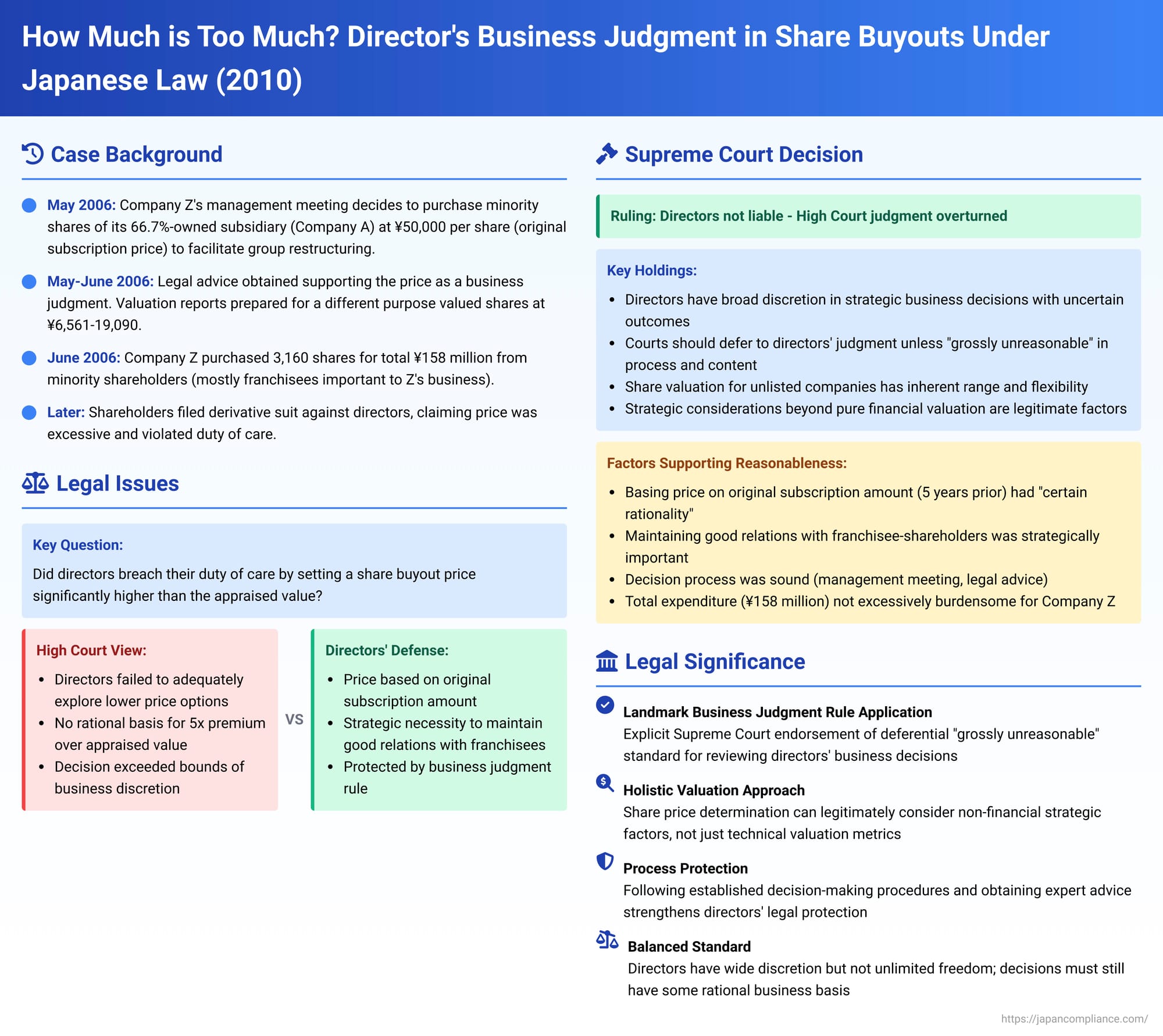

Directors of a company are often faced with complex decisions involving significant financial implications and uncertain future outcomes. When such decisions, made in good faith, result in losses or are perceived by shareholders as suboptimal, under what circumstances can directors be held personally liable for breaching their duty of care? The Japanese Supreme Court's decision on July 15, 2010, is a landmark ruling that provided significant clarification on the application of the "business judgment rule" (経営判断原則 - keiei handan gensoku) in reviewing such directorial decisions, particularly in the context of determining the purchase price for a subsidiary's shares during a corporate restructuring.

Restructuring and a Pricey Share Purchase: Facts of the Case

The case involved Company Z, a holding company overseeing a group primarily engaged in the real estate rental brokerage franchise business. Company Z held approximately 66.7% of the issued shares of a subsidiary, Company A. Other shareholders of Company A included various franchisees who were important to Company Z's core business operations.

Company Z formulated a strategic business restructuring plan aimed at enhancing group-wide efficiency and competitiveness. A key component of this plan was to have its main operating businesses conducted by wholly-owned subsidiaries, with Company Z functioning as the pure holding company. As part of this reorganization, Company A was slated to be merged into Company B, another wholly-owned subsidiary of Company Z, which would then consolidate real estate rental management and related services.

The decision-making process for acquiring the minority shares of Company A involved several steps:

- Management Meeting (May 11, 2006): Company Z's management meeting, an advisory body composed of all executive directors responsible for discussing overall group management policies, convened. The defendants, Y1 (Representative Director), Y2, and Y3 (Directors), were present. At this meeting, it was decided that:

- To ensure Company B remained a wholly-owned subsidiary after merging with Company A, it was necessary first to make Company A a wholly-owned subsidiary of Company Z.

- Considering the need for a smooth and efficient process, the preferred method for acquiring the minority shares in Company A was through voluntary purchase agreements with the existing shareholders, rather than a potentially more complex statutory share exchange, wherever possible.

- The appropriate purchase price for these shares was determined to be 50,000 yen per share. This figure was based on the original subscription price paid when Company A was established in 2001, approximately five years prior.

- Legal Advice: Company Z sought legal counsel regarding this proposal. The lawyer consulted opined that the pricing for a voluntary share purchase was essentially a business judgment, involving a balance of necessity and financial considerations. The lawyer considered the 50,000 yen per share price to be within an acceptable range, particularly if it served the purpose of maintaining good relations with the important franchisee shareholders of Company A, given that the total buyout sum was not excessively large.

- Valuation Reports for a Different Purpose: In preparation for a potential statutory share exchange (which would be needed for any shareholders who did not agree to a voluntary sale), Company Z had commissioned two audit firms to calculate an appropriate share exchange ratio. One report valued Company A's shares at 9,709 yen per share. The other report provided a valuation range of 6,561 yen to 19,090 yen per share, based on a comparable company analysis. These valuations were, therefore, significantly lower than the proposed 50,000 yen purchase price.

In June 2006, acting on the management meeting's decision, Company Z proceeded to purchase 3,160 shares of Company A from its minority shareholders (all except one shareholder who declined the offer) at the agreed price of 50,000 yen per share. The total expenditure for this buyout was 158 million yen. Subsequently, a statutory share exchange was carried out between Company Z and Company A to acquire the remaining shares.

Several shareholders of Company Z (the plaintiffs, X) initiated a shareholder derivative lawsuit against directors Y1, Y2, and Y3. They argued that the 50,000 yen per share purchase price was grossly excessive and that the directors, in approving this price, had breached their duty of care (zenkan chūi gimu) owed to Company Z. This breach, they claimed, caused financial damage to Company Z, for which the directors should be held personally liable under Article 423, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act.

The Legal Challenge: Duty of Care vs. Director Discretion

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court, judgment dated December 4, 2007) dismissed the shareholders' claim.

However, the appellate court (Tokyo High Court, judgment dated October 29, 2008) reversed this decision and found the directors liable. The High Court scrutinized the directors' decision-making process and found it lacking. It reasoned that the 50,000 yen purchase price was set without adequate investigation into whether a lower price might have been acceptable to the minority shareholders or a sufficient assessment of whether the anticipated benefits of making Company A a wholly-owned subsidiary justified such a significant premium over its appraised value (which the High Court deemed to be around 10,000 yen per share based on the valuation reports). The High Court concluded that there was no rational basis for the 50,000 yen price and that the directors' decision exceeded the bounds of permissible business discretion. The directors then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Verdict: Protecting Business Judgment

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and dismissed the plaintiffs' claim, ruling in favor of the directors.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Applying the Business Judgment Rule

The Supreme Court's judgment explicitly applied principles akin to the business judgment rule to assess the directors' conduct:

- Nature of the Decision as Strategic Business Judgment: The Court recognized that the acquisition of Company A's shares was not an isolated transaction but an integral part of Company Z's broader group restructuring plan. The formulation of such a plan, including evaluating the strategic advantages of converting Company A into a wholly-owned subsidiary, necessarily involves specialized business judgment concerning future forecasts and uncertain outcomes.

- Broad Discretion for Directors in Method and Price: In the context of such strategic decisions, the Court stated that directors have considerable discretion in determining the appropriate method and price for acquiring shares. This determination can legitimately take into account a wide range of factors, including not only the appraised valuation of the shares but also the strategic necessity of the acquisition, the financial burden on the acquiring company (Company Z), and the importance of executing the share acquisition smoothly and amicably, especially with parties crucial to the company's ongoing business.

- The Standard of Judicial Review: "Grossly Unreasonable": The Supreme Court articulated a deferential standard of review for such decisions. It held that as long as the process and content of the directors' decision are not "grossly unreasonable" (著しく不合理 - ichijirushiku fugōri), their actions will not be deemed a breach of the duty of care owed to the company.

- Application to the Facts – No Gross Unreasonableness Found:

- Method of Acquisition (Voluntary Purchase): The Court found that opting for voluntary purchase agreements was a reasonable method to ensure the smooth and amicable acquisition of Company A's shares, especially given the relationships with franchisees.

- Purchase Price (50,000 yen per share):

- The Court considered that Company A had been established only five years prior, and basing the purchase price on the original paid-in subscription amount (50,000 yen) was not, in itself, devoid of a certain rationality in general terms.

- Crucially, the minority shareholders of Company A included franchisees whom Company Z considered important for the ongoing success of its core franchise business. Maintaining a positive and cooperative relationship with these franchisees by ensuring an amicable buyout was deemed beneficial for the future business operations of Company Z and its entire group.

- The shares of Company A, being unlisted, were subject to a potentially wide range of valuations, and there was an expectation that the restructuring would enhance Company A's corporate value.

- Therefore, even though the valuation reports prepared for the separate purpose of a potential share exchange indicated lower share values (9,709 yen in one report, and a range of 6,561 to 19,090 yen in another), the directors' decision to set the voluntary purchase price at 50,000 yen per share, considering all the above factors, could not be described as "grossly unreasonable".

- Decision-Making Process: The decision to purchase the shares at this price was deliberated in Company Z's management meeting – an established advisory body for group-wide policy composed of all executive directors. Furthermore, legal advice was sought and obtained. The Supreme Court found nothing unreasonable in this decision-making process.

- Conclusion on Liability: Since the directors' judgment regarding the share purchase was not found to be grossly unreasonable either in its process or its content, the Supreme Court concluded that they had not breached their duty of care as directors of Company Z.

Analysis and Implications: Embracing the Business Judgment Rule in Japan

This 2010 Supreme Court decision is a landmark in Japanese corporate law as it represents one of the clearest endorsements and applications by the nation's highest court of the business judgment rule in a civil damages lawsuit against directors.

- The Business Judgment Rule (BJR) in Japan:

The BJR, which originated in U.S. case law, is a principle that generally protects directors from personal liability for honest, informed business decisions that, in hindsight, may turn out to have unfavorable consequences for the company. The rule's rationale includes the understanding that business inherently involves risk-taking (which is necessary for growth and innovation), that courts are not business experts and should avoid second-guessing complex decisions with the benefit of hindsight, and that shareholders implicitly accept a degree of risk when they entrust the company's management to directors.

In Japan, the BJR is not typically viewed as a doctrine that completely precludes judicial review of director conduct. Instead, it functions more as a standard of review that guides courts in assessing whether a breach of the duty of care has occurred. Courts will generally defer to the directors' judgment if the decision was made with due care in terms of process (e.g., adequate information gathering, deliberation) and if the substance of the decision was not irrational.

Prior to this Supreme Court ruling, Japanese lower courts often applied a two-step analysis (referred to in some commentaries as "Expression A"): first, examining whether there were careless errors in the directors' recognition of material facts (information gathering, investigation, and analysis); and second, assessing whether the decision made based on those facts was grossly unreasonable from the perspective of an ordinary business manager.

This 2010 Supreme Court decision articulated the standard slightly differently (sometimes called "Expression B"), focusing on whether the "decision-making process and content" were "grossly unreasonable". Legal commentators suggest that under this formulation, the scrutiny of factual recognition (information gathering) is likely subsumed within the examination of the "process," and perhaps also subject to the "grossly unreasonable" standard, implying that the extent of information gathering itself is a business judgment. - High Court vs. Supreme Court – A Difference in Application:

The divergence between the High Court and the Supreme Court in this case highlights the practical application of the BJR. The High Court, while acknowledging the principle of directorial discretion, engaged in a more intrusive review. It actively questioned whether the directors had sufficiently explored alternatives (like a lower purchase price) and whether the strategic benefits truly justified the premium paid, effectively substituting its own business judgment for that of the directors.

The Supreme Court, in contrast, adopted a more deferential stance. It did not demand that the directors prove they had optimized every aspect of the decision. Instead, it focused on whether the directors had considered relevant factors (such as the strategic importance of franchisee relations and the young age of Company A) and whether their ultimate decision, in light of these factors, fell within a range of reasonableness – specifically, whether it was "grossly unreasonable." The existence of rational considerations supporting the decision was key. - Justifying the 50,000 Yen Price:

The Supreme Court found the 50,000 yen price justifiable in this specific context. While using a five-year-old subscription price as a benchmark might seem weak in isolation (a point some commentators have raised), the Court viewed it as not entirely irrational for a relatively young, unlisted company, especially when combined with the significant strategic imperative of maintaining goodwill with the franchisee shareholders of Company A. These franchisees were vital to Company Z's core business, making an amicable buyout at a price they perceived as fair a valuable strategic objective in itself. - The Importance of Process:

The Supreme Court's explicit mention of the deliberations in the management meeting and the seeking of legal advice underscores the importance of a sound decision-making process. Following established internal procedures and obtaining external expert opinions can provide strong evidence that directors acted with due care, even if the decision later faces scrutiny. - The BJR in Japan After This Decision:

This ruling has been influential. Subsequent lower court decisions frequently reference the "grossly unreasonable process and content" standard articulated here. However, variations of the older two-step "Expression A" analysis also continue to appear.

The academic debate continues regarding the precise relationship between the assessment of the factual basis of a decision and the evaluation of its substantive rationality. Some argue that these are deeply intertwined and that the adequacy of information gathering is itself a business judgment. The overarching trend, however, is clear: Japanese courts will afford directors substantial discretion, particularly in complex strategic matters, but this discretion is not unlimited. A robust process and a decision that is not devoid of any rational business basis are essential. The specific "width" of this discretion may also vary depending on the nature of the transaction or the type of business judgment involved.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 15, 2010, decision significantly reinforced the application of the business judgment rule in Japanese corporate law. It provides directors with a considerable degree of protection when making complex strategic decisions, such as determining share purchase prices in a corporate restructuring, provided that their decision-making process is diligent and the substance of their decision is not "grossly unreasonable." This ruling signals a judicial willingness to defer to the business expertise of directors and to avoid imposing liability based on hindsight, so long as these fundamental conditions of careful process and rational judgment are met. It serves as a critical guide for directors navigating the challenges of corporate management and for shareholders assessing the accountability of those directors.