How Long Does a Condominium Association Have to Collect Unpaid Fees? A 2004 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on the Statute of Limitations

Date of Judgment: April 23, 2004

Case Number: 2002 (Ju) No. 248 (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench)

Introduction

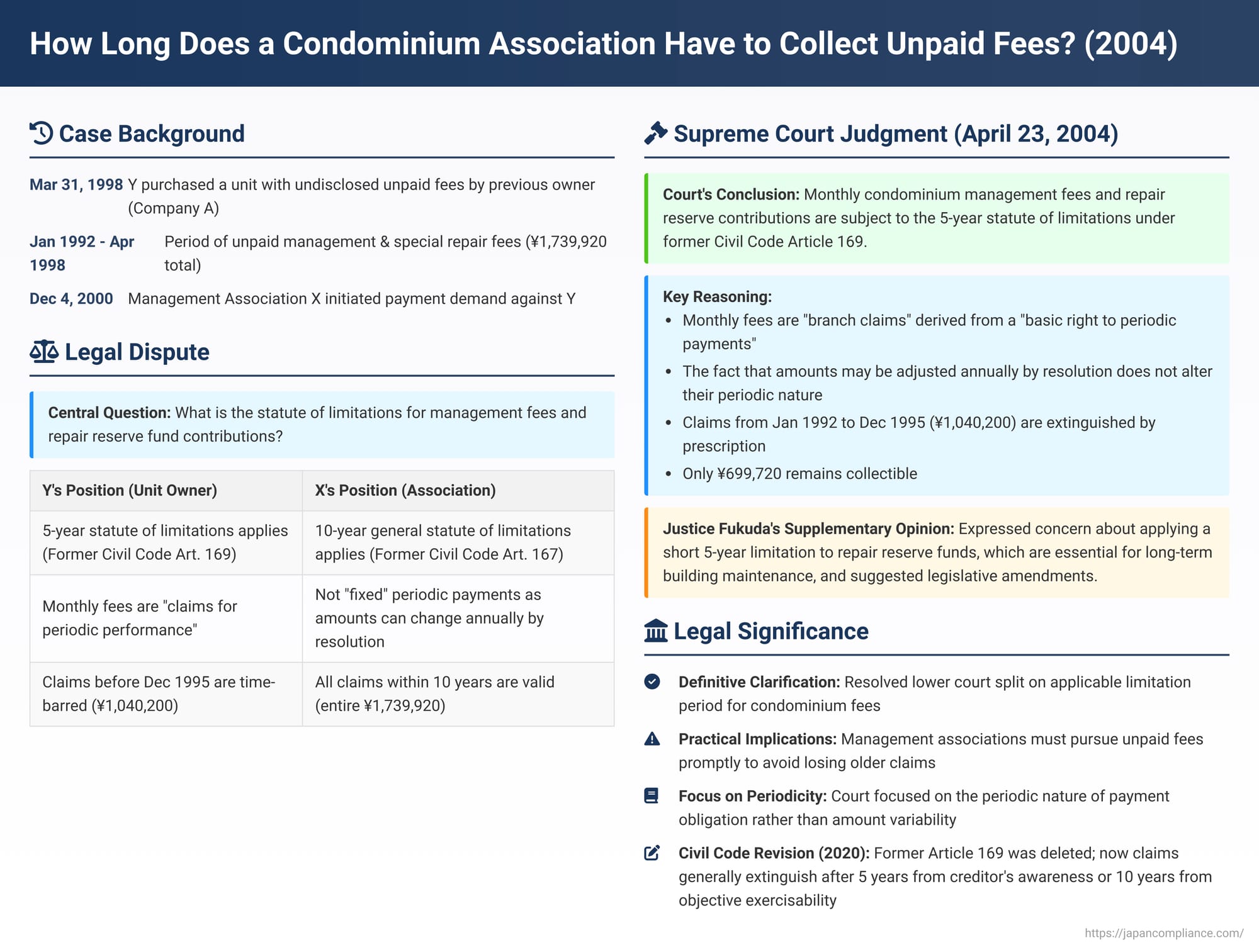

The financial health of a condominium management association in Japan hinges on the consistent payment of management fees and contributions to repair reserve funds by its unit owners. These funds are essential for daily operations, maintenance of common areas, and crucial long-term repairs and renovations. However, delinquencies in these payments are a persistent issue. When a unit owner fails to pay, and especially when a unit changes hands with outstanding fees, a critical legal question arises: What is the time limit, or statute of limitations (消滅時効 - shōmetsu jikō), for the management association to legally recover these unpaid amounts?

A Supreme Court of Japan decision on April 23, 2004, provided a definitive answer to this question under the then-existing Japanese Civil Code, clarifying whether such claims were subject to a shorter 5-year prescription period applicable to periodic payments or a longer general prescription period.

Facts of the Case

The case involved X, the Management Association of "A Condominium," and Y, who became a unit owner in this condominium.

Background of Ownership and Unpaid Fees:

- On March 31, 1998, Y purchased a unit in A Condominium from the previous owner, Company A. Y completed the ownership transfer registration on May 1, 1998.

- Unbeknownst to Y at the time of purchase, or as a liability Y inherited, Company A had a history of unpaid management fees and special repair fees (collectively referred to as "management fees, etc." - 管理費等, kanrihi tō). These delinquencies spanned from January 1992 to April 1998, and the total outstanding amount was ¥1,739,920.

Condominium Bylaws Regarding Fees:

The bylaws (規約 - kiyaku) of A Condominium stipulated:

- Unit owners were obligated to pay management fees (for ongoing management of common areas) and special repair fees to the Management Association X.

- The specific amounts for these fees were to be calculated based on each unit owner's co-ownership share in the common areas and were subject to annual approval by a resolution of the general meeting of unit owners as part of the association's budget.

- The special repair fees were to be accumulated in a dedicated repair reserve fund (修繕積立金 - shūzen tsumitatekin).

- The Association X was to collect the fees for the upcoming month by the end of the current month, typically through automatic bank transfers from accounts set up by each unit owner.

- Any changes to fee amounts, collection methods, or related matters also required a resolution of the general meeting.

Legal Proceedings:

- On December 4, 2000, Management Association X initiated a formal payment demand procedure (支払督促 - shiharai tokusoku) against Y, the new owner, seeking payment of the ¥1,739,920 in unpaid fees accrued by the previous owner, Company A. Under Japan's Condominium Ownership Act (COA) Article 8, a subsequent owner is generally liable for the unpaid management fee obligations of their predecessor.

- Y objected to this payment demand, which automatically transitioned the matter into a formal lawsuit.

Y's Statute of Limitations Defense:

In the lawsuit, Y's primary defense was the statute of limitations. Y argued that:

- The claims for monthly management fees, etc., constituted "claims for periodic performance" (定期給付債権 - teiki kyūfu saiken) as defined under Article 169 of Japan's Civil Code (the version in effect before significant revisions in 2020, hereafter "former Civil Code").

- Such claims, under former Civil Code Article 169, were subject to a relatively short prescription period of five years.

- Therefore, any portion of the claimed fees for which the payment deadline had passed more than five years prior to X's initiation of legal action (December 4, 2000) was extinguished by prescription. This specifically applied to the fees due from January 1992 up to and including December 1995, which Y calculated to be ¥1,040,200 of the total claim.

High Court Ruling:

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the appellate court in this instance, had rejected Y's statute of limitations defense.

- The High Court reasoned that although the management fees, etc., were paid monthly, their annual total amount was not fixed indefinitely. Instead, the amounts could be increased or decreased each year by a resolution of the general meeting, depending on the anticipated costs of managing the common areas.

- Because of this potential for annual variation based on general meeting decisions, the High Court concluded that these fees did not possess the character of a "basic right to periodic payments" (基本権たる定期金債権 - kihonken taru teikikin saiken) that would give rise to "branch claims" (支分権 - shibunken) subject to the 5-year prescription.

- Instead, the High Court applied the general prescription period for contractual claims under former Civil Code Article 167, Paragraph 1, which was ten years. Under this longer period, none of the claimed fees would have been extinguished.

Y, disagreeing with the High Court's interpretation, appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its decision of April 23, 2004, partially overturned the High Court's ruling and found in favor of Y regarding the statute of limitations.

1. Characterization of the Management Fee Claims:

The Supreme Court began by analyzing the nature of the claims for management fees, etc., in question:

- These claims arise based on the provisions within the Condominium's management bylaws.

- The specific monetary amount for each period is determined by resolutions passed at the general meetings of the unit owners.

- They are stipulated to be paid on a monthly basis through a prescribed collection method.

2. Application of Former Civil Code Article 169:

Based on this characterization, the Supreme Court held:

- Claims for condominium management fees, etc., payable monthly, are properly considered "branch claims" (shibunken) that derive from an underlying "basic right to periodic payments" (kihonken taru teikikin saiken).

- As such, these monthly claims fall squarely within the definition of claims for which payment of money or other things is fixed at yearly or shorter regular intervals, as stipulated in former Civil Code Article 169. This article prescribed a 5-year period for the extinguishment by prescription of such claims.

- The fact that the specific monetary amount of these fees might be increased or decreased from time to time (e.g., annually) by a resolution of the general meeting – due to fluctuations in the actual or anticipated costs of managing the common areas – does not alter this fundamental conclusion. The periodic nature of the obligation to pay remains, even if the amount per period is variable by collective decision.

3. Conclusion on Prescription:

- Applying this reasoning, the Supreme Court found that the portion of the management fees, etc., claimed by X that pertained to the period from January 1992 to December 1995 (totaling ¥1,040,200) had indeed been extinguished by the 5-year statute of limitations, as Y had argued.

- Consequently, Management Association X's claim against Y was valid only for the remaining amount of ¥699,720, plus applicable interest for late payment from December 13, 2000 (the day after Y was served with the initial payment demand).

The Supreme Court thus found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of the law and modified the judgment accordingly.

Justice Fukuda's Supplementary Opinion

While concurring with the majority's legal interpretation under the then-prevailing Civil Code, Justice Fukuda appended a supplementary opinion expressing significant concerns, particularly regarding the application of a short 5-year statute of limitations to special repair fees, i.e., contributions to the repair reserve fund (修繕積立金 - shūzen tsumitatekin).

- He emphasized that regular contributions to a repair reserve fund are absolutely essential for addressing the inevitable deterioration of common areas over time and for undertaking necessary large-scale repairs. These funds are indispensable for maintaining the asset value of the condominium, which ultimately benefits each individual unit owner.

- He characterized the obligation to contribute to the repair reserve fund as a fundamental and unavoidable burden inherent in the condominium ownership relationship.

- Given the critical nature of these funds, Justice Fukuda expressed unease that a short 5-year prescription period could allow delinquent unit owners to easily escape their responsibility for these vital contributions. This could unfairly burden diligent owners and jeopardize the long-term maintenance of the building.

- He strongly suggested that appropriate measures, explicitly including legislative amendments, should be thoroughly considered to prevent such outcomes and ensure the collectability of repair reserve funds, thereby protecting the integrity of condominium management and asset preservation.

Analysis and Broader Implications

The 2004 Supreme Court decision was a landmark for condominium management associations and unit owners in Japan under the legal framework of the time.

1. Understanding Former Civil Code Provisions on Prescription:

The case revolved around prescription periods set in the pre-2020 Civil Code:

- Former Article 168, Paragraph 1 (first part): Dealt with the "basic right to periodic payments" (e.g., the right to receive an annuity). This basic right itself was subject to a 20-year prescription period, starting from the due date of the first installment.

- Former Article 169: Dealt with the individual "branch claims" arising from such a basic right – specifically, claims for money or other goods due at yearly or shorter regular intervals (e.g., monthly rent, annual interest payments, monthly annuity installments). These branch claims were subject to a shorter 5-year prescription period.

The Supreme Court's decision firmly placed monthly condominium management fees and repair reserve contributions into the category of "branch claims" under former Article 169, stemming from a basic (implied) right of the association to collect these fees periodically from its members.

2. Legislative Intent Behind the Shorter 5-Year Prescription for Periodic Payments:

The rationale for the shorter 5-year period in former Article 169 for such regularly recurring, often smaller, payments was generally understood to be twofold:

- Prompt Collection and Evidence Preservation: Such payments are typically expected to be made and collected promptly. It was considered that creditors would not usually let many installments accumulate, and debtors would not ordinarily keep payment receipts for very long periods.

- Preventing Accumulation of Crippling Debt: Allowing many small, overdue periodic payments to accumulate over a long period (e.g., 10 years) could result in a very large total debt that could overwhelm the debtor. The shorter 5-year limit was seen as a way to prevent this.

3. Clarification After Lower Court Uncertainty:

Prior to this 2004 Supreme Court ruling (and even following a 1993 Supreme Court case that had implicitly supported a 5-year period without explicitly deciding the point for all types of fees), there had been a notable split among lower courts. Some applied the 5-year period of former Article 169, while others, like the High Court in this case, applied the general 10-year period for contractual claims from former Article 167, Paragraph 1. This Supreme Court decision provided much-needed definitive clarification.

4. High Court's Reasoning for a 10-Year Period (and the Supreme Court's Rebuttal):

The High Court had argued that because the specific monetary amount of the management fees, etc., could be changed annually by a resolution of the general meeting, these were not "fixed" periodic payments in the sense required for former Article 169. The Supreme Court effectively dismissed this line of reasoning, focusing instead on the periodic nature of the obligation to make a payment each month rather than on the absolute immutability of the amount of each payment. The underlying obligation to pay a collectively determined fee each month was the key.

5. Practical Impact on Management Associations:

The definitive establishment of a 5-year prescription period for these claims under the old Civil Code strongly emphasized the need for condominium management associations to be diligent and proactive in monitoring payments and pursuing unpaid fees promptly. Allowing delinquencies to accumulate for more than five years carried a significant risk of those older claims becoming legally unrecoverable.

6. Considerations Under the Revised Civil Code (Effective April 2020):

It is crucial to note that Japan's Civil Code underwent a major revision concerning the law of obligations, including the rules on prescription, which came into effect on April 1, 2020.

- New General Prescription Rule: The primary new rule (Article 166, Paragraph 1 of the revised Civil Code) states that a claim is extinguished by prescription if:

- The creditor does not exercise the right for five years from the time the creditor became aware that the right could be exercised (subjective starting point).

- The creditor does not exercise the right for ten years from the time the right could objectively be exercised (objective starting point).

The claim is extinguished when the earlier of these two periods expires.

- Deletion of Former Article 169: The specific provision for a 5-year prescription for periodic payment claims (former Article 169) was deleted in the 2020 revision. The drafters reasoned that the new general 5-year rule (from the creditor's awareness) would adequately cover most situations involving periodic payments, as creditors (like management associations) are typically aware when each installment (like a monthly fee) becomes due and thus exercisable.

- Potential Change in Effect: In most standard cases involving monthly management fees, where the association is aware of the due dates, the 5-year period from awareness under the new Civil Code would likely yield the same outcome as the 5-year period under former Article 169. However, a theoretical difference could arise: if a management association was, for some unusual reason, unaware that a particular fee installment had become due and exercisable, the prescription period under the new Civil Code could potentially extend to 10 years (from the objective date of exercisability). This might, in rare cases, lead to a longer period than the flat 5 years under the old law, which could reintroduce concerns about debt accumulation for certain types of periodic claims if "awareness" is delayed.

- The "Basic Right to Periodic Payments" Under the New Code: The concept of a "basic right to periodic payments" (formerly teikikin saiken) is addressed in the revised Civil Code Article 168. This article now states that such a basic right is extinguished if not exercised for ten years from the time the creditor became aware that the first branch claim (e.g., the first unpaid monthly fee) could be exercised, OR for twenty years from the time that first branch claim could objectively be exercised.

However, as legal commentators have pointed out (and as was generally understood under the old Code for analogous rights like the basic right to collect rent or interest), the fundamental obligation of a current unit owner to pay ongoing management fees is likely not the type of "basic right" that Article 168 intends to extinguish in its entirety merely because some past installments have become time-barred. As long as a person remains a unit owner, their obligation to pay future, duly levied fees continues to arise from their status and the bylaws. The prescription would typically apply to individual overdue installments, not to the underlying, ongoing obligation to pay future fees.

Concluding Thoughts

The 2004 Supreme Court decision provided crucial clarity under the then-applicable Civil Code, establishing a 5-year statute of limitations for individual monthly installments of condominium management fees and repair reserve fund contributions. This ruling underscored the necessity for management associations to maintain diligent and timely collection practices to avoid losing the right to recover older debts.

While the specific Civil Code articles have since been revised, the case's fundamental reasoning—that these fees are periodic obligations—remains relevant for understanding their legal character. Justice Fukuda's supplementary opinion also brought to the fore an important and ongoing policy concern: ensuring the robust collectability of repair reserve funds, which are vital for the long-term health and sustainability of condominium buildings. This concern continues to be relevant as condominium communities in Japan age and face increasing needs for large-scale repairs and renovations.