Hometown Tax Wars: Japan's Supreme Court Curbs Ministerial Power in Furusato Nōzei Designations

A Third Petty Bench Ruling from June 30, 2020

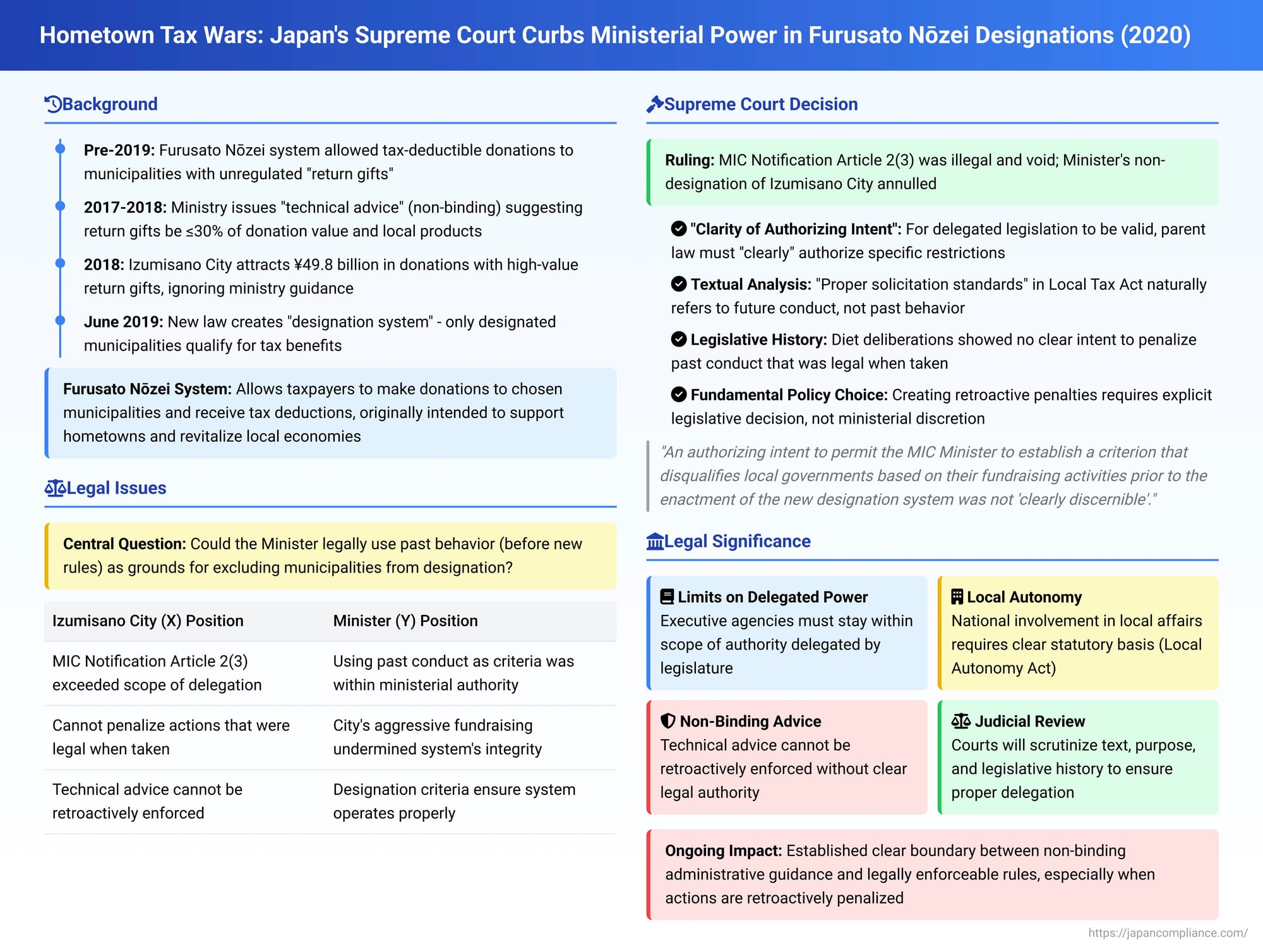

Japan's "Furusato Nōzei" or "Hometown Tax Donation" system, introduced to allow taxpayers to contribute to municipalities of their choice (often their actual hometowns or areas they wish to support) and receive tax deductions in return, quickly became a popular, yet controversial, program. The system's unintended consequence was an escalating "return gift competition" among local governments, vying for donations by offering increasingly lavish local products or other benefits to donors. This "competition" led to government intervention and, ultimately, a significant legal battle that reached the Supreme Court. A ruling by the Third Petty Bench on June 30, 2020 (Reiwa 2 (Gyo Hi) No. 68), involving Izumisano City, addressed the crucial question of how far a government minister could go in setting rules for this system, particularly when those rules effectively penalized past actions that were not illegal at the time.

The Furusato Nōzei System and Its Challenges

The Furusato Nōzei system allows individuals to make donations to prefectural or municipal governments. In return, the donor receives a special deduction (特例控除 - tokurei kōjo) on their income tax and local inhabitant taxes for the donated amount exceeding a certain threshold, up to a specified limit. To attract these donations, many local governments began offering "return gifts" (返礼品 - henreihin) to donors. This practice, while not initially regulated by law, led to what was widely described as an overheated "return gift competition," with some municipalities offering high-value items that bore little relation to their local products or whose cost consumed a large percentage of the donation.

The Ministry for Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), under its Minister (Y, the defendant/appellee), attempted to guide local governments through "technical advice" (技術的助言 - gijutsuteki jogen). These advisories suggested, for instance, that the procurement cost of return gifts should be kept at 30% or less of the donation amount and that gifts should primarily be local products. However, some local governments, including Izumisano City (represented by its Mayor, X, the plaintiff/appellant), did not adhere to this non-binding advice and continued to attract substantial donations by offering high-value return gifts. Izumisano City, for example, saw its Furusato Nōzei donations rise dramatically, reaching nearly 49.8 billion yen in fiscal year 2018, the highest among all local governments in Japan for that year.

Legislative Reform: The Designation System

To address these concerns and ensure the "proper operation" of the Furusato Nōzei system, the Local Tax Act (地方税法 - Chihō Zeihō) was revised, with the new provisions (本件改正規定 - honken kaisei kitei) coming into effect from June 1, 2019. This revision introduced a "Furusato Nōzei Designation System". Under this new system, only donations made to those local governments specifically designated by the MIC Minister would qualify for the special tax deductions.

The revised Local Tax Act (specifically Article 37-2, paragraph 2, and the parallel Article 314-7, paragraph 2) stipulated that the Minister would designate local governments that conform to certain criteria. These criteria included:

- Statutory Return Gift Standards (法定返礼品基準 - hōtei henreihin kijun): The procurement cost of return gifts must be 30% or less of the donation value, and the gifts must be local products (goods produced or services provided within the local government's area) meeting criteria set by the Minister.

- Proper Solicitation Standards (募集適正基準 - boshū tekisei kijun): These were standards concerning the proper conduct of soliciting donations, to be determined by the MIC Minister.

The Disputed MIC Notification and Izumisano's Exclusion

Acting on the authority to set the "proper solicitation standards," the MIC Minister issued Notification No. 179 of 2019 (平成31年総務省告示第179号 - hereinafter "the MIC Notification" or 本件告示 - honken kokuji), effective from June 1, 2019. A key and controversial provision within this Notification was Article 2, item 3. This item stipulated that to be designated, a local government must not be one that, during the period from November 1, 2018, to the date of its application for designation (a period largely before the new designation system came into effect), had:

- Solicited donations using methods contrary to the spirit of the Furusato Nōzei system (as defined in Article 1 of the Notification, emphasizing gratitude and support for hometowns or chosen regions, and enabling taxpayers to decide the use of their taxes).

- Thereby exerted a significant influence on other local governments.

- And, as a result, received a remarkably larger amount of donations compared to other local governments that solicited donations in line with the system's spirit.

When Izumisano City applied for designation under the new system, the MIC Minister refused the designation (this refusal is termed 本件不指定 - honken fushitei). One of the primary reasons given for this non-designation was that Izumisano City's past fundraising practices, particularly its high-value return gifts and "Amazon gift card campaigns" between November 2018 and Spring 2019, fell afoul of Article 2, item 3 of the MIC Notification.

After an unsuccessful appeal to the Committee for Settling Disputes between National and Local Governments (which recommended the Minister reconsider, questioning the legality of the Notification criterion), Izumisano City's Mayor, X, filed a lawsuit seeking the annulment of the Minister's non-designation decision. The Osaka High Court, acting as the court of first instance for this type of administrative litigation involving national government actions against local governments, ruled in favor of the Minister, finding the MIC Notification criterion to be within the scope of legal delegation and the non-designation of Izumisano City to be lawful.

The Supreme Court's Decision of June 30, 2020

The Supreme Court overturned the Osaka High Court's decision and annulled the MIC Minister's non-designation of Izumisano City. The Court found that the critical provision of the MIC Notification (Article 2, item 3) was illegal and void because it exceeded the scope of authority delegated to the Minister by the revised Local Tax Act.

Core Reasoning: Exceeding Delegated Authority and the Need for "Clarity of Authorizing Intent"

The Supreme Court's reasoning centered on the limits of delegated legislative power:

- Delegation and Its Limits: The Local Tax Act (Art. 37-2(2)) clearly delegates the task of formulating specific designation criteria (the "proper solicitation standards") to the MIC Minister. The MIC Notification Article 2, item 3, was established based on this delegation. However, because these designation criteria constitute a form of national government "involvement" (関与 - kan'yo) in the affairs of local governments, their establishment requires a legal basis, not only from the delegating statute but also in light of the principle of "statutory basis for national government involvement" found in Article 245-2 of the Local Autonomy Act. Therefore, if Article 2, item 3 of the Notification exceeds the scope of delegation provided by the Local Tax Act, the part that exceeds this scope is illegal and void.

- Interpretation of the Disputed Notification Provision: The Court interpreted Article 2, item 3 of the Notification as aiming to disqualify local governments that, prior to the introduction of the new designation system, had engaged in fundraising methods deemed contrary to the Furusato Nōzei system's spirit and had received excessively large sums of donations as a result. This was ostensibly to ensure fairness with other local governments and gain their acceptance of the new system. In essence, this provision meant that disqualification could be based on past fundraising performance itself, regardless of how a local government intended to conduct its fundraising activities during the future designation period under the new rules.

- Scrutiny of the Delegation – "Clarity of Authorizing Intent": The Court noted that Article 2, item 3 of the Notification, by looking at past conduct often taken despite prior (non-binding) "technical advice" from the Minister, had the effect of imposing a disadvantageous treatment for not having followed that advice. While Local Autonomy Act Article 247, paragraph 3 prohibits national government officials from meting out disadvantageous treatment to a local government for not complying with such advice, this prohibition applies when there is no legal basis for such treatment. If a law explicitly authorized such treatment, it might be permissible. However, if, as in this case, the disadvantageous treatment stems from a delegated order (the Notification), then for that order to be valid and not exceed the scope of delegation, the "authorizing intent" (授権の趣旨 - juken no shushi) of the parent Local Tax Act to permit the creation of such a backward-looking, conduct-penalizing criterion must be "clearly discernible" (明確に読み取れる - meikaku ni yomitoreru) from the Act's provisions. This standard of "clarity of authorizing intent" echoes a similar standard applied by the Court in a 2013 case concerning online pharmacy sales.

- Analysis of Authorizing Intent in the Local Tax Act: The Supreme Court then meticulously examined whether such a "clear authorizing intent" existed in the Local Tax Act:

- (i) Textual Interpretation of the Act: The Court found that the term "proper solicitation standards" in the Local Tax Act, read naturally, refers to the manner of soliciting donations during the future designation period. It is a set of criteria to determine if a local government will conduct its fundraising appropriately under the new system. It is difficult to interpret the Act's text as contemplating criteria that would disqualify a local government based solely on its past fundraising record. Doing so would also create an imbalance with other provisions of the Act that allow a local government whose designation is revoked (for future non-compliance) to reapply for designation after two years.

- (ii) Purpose of Delegation to the Minister: The Court reasoned that the Local Tax Act delegated the formulation of specific solicitation standards to the Minister primarily because these criteria require expert knowledge of local administration, finance, and tax systems, and need to be flexible enough to adapt to changing circumstances—matters not suitable for exhaustive statutory detailing. However, the decision of whether to establish a criterion that effectively disqualifies local governments based on their past conduct (particularly conduct that was not illegal at the time) is a fundamental policy choice involving political judgment. Such a decision, imposing a significant and ongoing disadvantage, is not the type of technical or flexible matter appropriately left to ministerial discretion.

- (iii) Legislative Process and Intent: The Court reviewed the Diet deliberations leading to the revised Local Tax Act. While the general aim was to curb excessive return gifts and normalize the system, it was not made clear during these deliberations that past fundraising performance before the new system's rules were in place would be a ground for disqualification from the new designation system. At least, it was not explicitly stated that a criterion like Article 2, item 3 of the MIC Notification, focusing on past conduct, was intended by the legislature. The discussions largely centered on ensuring proper conduct going forward under the new legal framework.

- Conclusion on the Validity of Notification Article 2, item 3: Based on the textual interpretation of the Local Tax Act, the purpose of the delegation to the Minister, and the legislative process, the Supreme Court concluded that an authorizing intent to permit the MIC Minister to establish a criterion that disqualifies local governments based on their fundraising activities prior to the enactment of the new designation system was not "clearly discernible". Therefore, Article 2, item 3 of the MIC Notification, insofar as it related to past fundraising conduct, was illegal and void for exceeding the scope of delegation granted by the Local Tax Act.

Since this was a key reason for the Minister's refusal to designate Izumisano City, and the Court also found the Minister's other stated reasons for non-designation insufficient, the non-designation decision itself was annulled.

Key Legal Principles Reinforced

This ruling highlights several crucial principles of Japanese administrative and constitutional law:

- Limits on Delegated Legislation: Executive agencies, when making rules under authority delegated by the legislature, must not go beyond the scope of that delegation. Regulations that overstep these bounds are illegal and void.

- Statutory Basis for National Government Involvement: National government actions that constitute "involvement" (関与 - kan'yo) in the affairs of local governments, such as setting designation criteria, must have a clear basis in law (Local Autonomy Act, Art. 245-2).

- Prohibition on Disadvantageous Treatment for Non-Adherence to Advice: Local governments generally cannot be subjected to disadvantageous treatment merely for not following non-binding administrative advice (Local Autonomy Act, Art. 247(3)). If a delegated order effectively creates such disadvantageous treatment, its legal foundation in the parent statute must be exceptionally clear.

- The "Clarity of Authorizing Intent" Standard: The case further solidifies the standard that for delegated legislation to be valid, particularly when it imposes significant restrictions or disadvantages, the intent of the parent law to authorize such specific regulations must be "clearly discernible". This provides an important check on executive rulemaking.

The Broader Context: Technical Advice vs. Legal Rules

The background of the case, involving "technical advice" from the MIC Minister that Izumisano City largely ignored, is important. The Supreme Court's decision implicitly underscores the distinction between non-binding administrative guidance and legally enforceable rules. While Izumisano City's aggressive fundraising tactics were controversial and went against ministerial advice, those tactics were not, at the time, explicitly illegal under the then-existing statutory framework. The Court's ruling suggests that if the government wished to penalize or disqualify local governments based on such past conduct, it should have sought explicit and clear authorization from the Diet in the primary legislation itself, rather than attempting to achieve this through a ministerial notification whose authorizing basis in the parent law was, at best, ambiguous for such a purpose. One of the supplementary opinions noted the difficulty the government might have faced in getting explicit statutory approval for a measure that retroactively problematized past actions that were not illegal when undertaken, and suggested that the use of a Notification might have been an attempt to navigate this difficulty. The Court's rigorous application of the "clarity of authorizing intent" standard effectively closed this avenue.

Significance of the Ruling

The Izumisano City Furusato Nōzei case is a significant decision that:

- Provides a robust check on the power of government ministries to enact rules that affect the autonomy and operations of local governments, especially when those rules have retroactive or punitive implications not clearly sanctioned by primary legislation.

- Reinforces the necessity for clear legislative mandates when executive actions lead to restrictions or penalties, upholding the principle of legislative supremacy.

- Demonstrates the judiciary's role in meticulously examining the text, purpose, and legislative history of parent statutes to ensure that administrative rulemaking remains faithful to, and does not overstep, the authority granted by the Diet.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2020 ruling in favor of Izumisano City is a powerful reminder that even well-intentioned policy objectives pursued through administrative rulemaking must have a clear and legitimate foundation in primary legislation. The judgment emphasizes that the scope of delegated legislative power is not limitless and that the judiciary will carefully scrutinize administrative regulations to ensure they conform to the empowering statutes, particularly when principles of local autonomy, fairness in the application of new rules, and the clarity of legislative intent are at stake. This decision serves as an important precedent for the relationship between national and local governments and the boundaries of administrative power in Japan.