Can You Stop a CAA Cease-and-Desist? Preliminary Injunctions Against Misleading-Advertising Orders in Japan

TL;DR

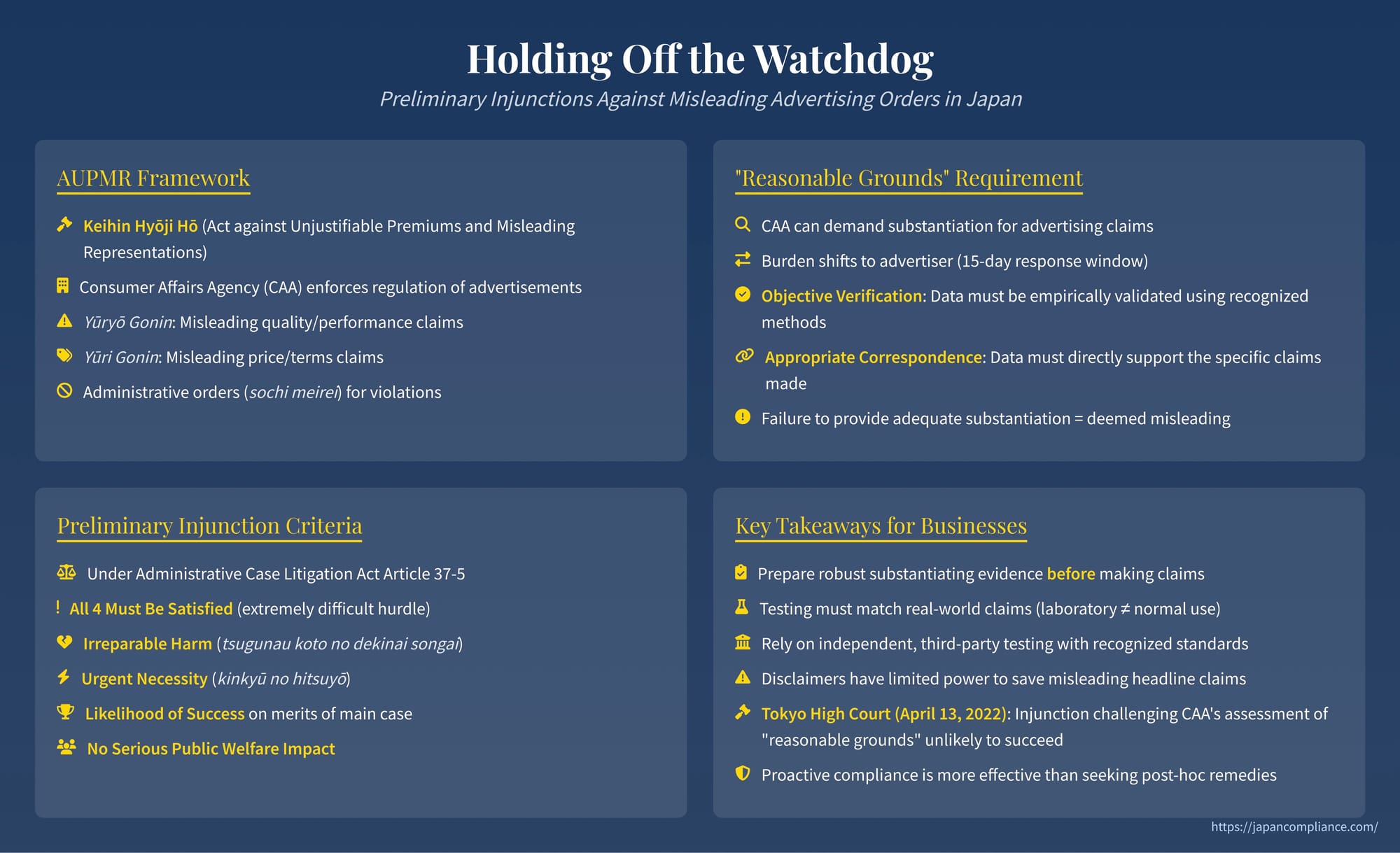

- The article explains why obtaining a preliminary injunction against Consumer Affairs Agency (CAA) orders under Japan’s Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations (AUPMR) is exceptionally difficult.

- It details the “reasonable grounds” substantiation rule, analyses the Tokyo High Court’s 13 Apr 2022 decision, and offers compliance take-aways for businesses advertising in Japan.

Table of Contents

- Japan's Advertising Regulations: The AUPMR Framework

- The "Reasonable Grounds" Requirement and CAA Enforcement

- Seeking Interim Relief: Preliminary Injunctions Against Administrative Actions

- The Tokyo High Court Decision (April 13 2022): A Case Study

- Key Takeaways for Businesses Marketing in Japan

- Conclusion

Japan maintains a strict regulatory environment concerning advertising claims, primarily enforced through the Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations (不当景品類及び不当表示防止法 - Futō Keihinrui oyobi Futō Hyōji Bōshi Hō, commonly known as the Keihin Hyōji Hō or AUPMR). The Consumer Affairs Agency (CAA - 消費者庁 Shōhisha-chō), the primary enforcement body, possesses the authority to issue administrative orders (措置命令 - sochi meirei), such as cease-and-desist directives, against businesses whose advertising is deemed misleading. Facing such an order can have significant reputational and operational consequences.

While businesses can challenge the legality of these orders through administrative litigation, the process can be lengthy. This raises the question: can a company obtain temporary relief, such as a preliminary injunction (仮の差止め - kari no sashitome), to halt an impending administrative order while its legality is contested in court? A Tokyo High Court decision on April 13, 2022 (Reiwa 4) provides valuable insights into the significant hurdles businesses face when seeking such interim relief against CAA actions under the AUPMR.

Japan's Advertising Regulations: The AUPMR Framework

The AUPMR aims to protect consumers by prohibiting representations that could mislead them about the quality, price, or other terms of goods and services. Key prohibitions relevant to advertising claims include:

- Misleading Representations Concerning Quality (優良誤認 - Yūryō Gonin): Representations that mislead consumers into believing a product or service is significantly superior in quality, standards, or content than it actually is, or significantly superior to those of competitors, without reasonable grounds.

- Misleading Representations Concerning Advantageous Terms (有利誤認 - Yūri Gonin): Representations regarding price or other transaction terms that mislead consumers into believing they are substantially more advantageous than they actually are, or substantially more advantageous than those offered by competitors.

The "Reasonable Grounds" Requirement and CAA Enforcement

A crucial aspect of the AUPMR, particularly for claims regarding product performance or efficacy, is the "unsubstantiated advertising regulation" (fujisshō kōkoku kisei) derived from Article 7, Paragraph 2.

- Demand for Substantiation: If the CAA suspects that a representation about a product's quality or performance (potentially falling under yūryō gonin) might lack sufficient basis, it can require the business operator to submit data demonstrating "reasonable grounds" (gōriteki konkyo) for the claim within a specified period (typically 15 days).

- Reversal of Burden of Proof: Failure to submit adequate data within the deadline, or submission of data that the CAA does not recognize as providing reasonable grounds, results in the representation being deemed misleading under Article 5, Item 1 (misleading representation concerning quality) for the purpose of issuing an administrative order. This effectively shifts the burden to the advertiser to proactively substantiate their claims when challenged.

- What Constitutes "Reasonable Grounds"? According to CAA guidelines (e.g., 「不当景品類及び不当表示防止法第7条第2項の運用指針」 - Guidelines for the Application of Article 7, Paragraph 2 of the AUPMR), the submitted data must meet two key criteria:

- Objective Verification: The data must be objective and empirically validated. This generally means results obtained through tests or surveys, or the views of experts/specialized organizations or academic literature. Testing methods should ideally align with recognized academic or industry standards, or, if none exist, be reasonable based on social norms and empirical rules. Mere consumer testimonials are usually insufficient unless collected through statistically objective methods.

- Appropriate Correspondence: The content proven by the submitted data must directly and appropriately correspond to the specific effects or performance claimed in the advertisement. A laboratory test under specific conditions might not substantiate a claim about effectiveness in general real-world use.

If the CAA determines that the submitted grounds are insufficient, it can issue a sochi meirei ordering the business to cease the misleading representation, disseminate a corrective notice to the public, and implement measures to prevent recurrence. Financial penalties (kachōkin) can also be imposed in certain cases.

Seeking Interim Relief: Preliminary Injunctions Against Administrative Actions

A business notified of the CAA's intent to issue a sochi meirei can file a lawsuit challenging the anticipated order's legality. However, given the potential immediate damage to reputation and business operations from such an order, seeking a preliminary injunction to prevent its issuance pending the court's final decision is a theoretical option under Japan's Administrative Case Litigation Act (Gyōsei Jiken Soshō Hō - ACLA).

Article 37-5 of the ACLA governs preliminary injunctions sought before an administrative disposition (like a sochi meirei) is made. Obtaining such an injunction is exceptionally difficult and requires the court to find that all of the following stringent conditions are met:

- Irreparable Harm: The execution of the administrative order would cause "harm that cannot be compensated" (償うことのできない損害 - tsugunau koto no dekinai songai). This generally refers to non-monetary harm or damage that is extremely difficult to restore later, such as severe reputational damage or the irretrievable loss of business opportunities.

- Urgent Necessity: There must be an "urgent need" (緊急の必要 - kinkyū no hitsuyō) to avoid this irreparable harm.

- Likelihood of Success on the Merits: The court must find that the main lawsuit challenging the legality of the impending administrative order appears to have merit (本案について理由があるとみえる - hon'an ni tsuite riyū ga aru to mieru). This is often the highest hurdle.

- No Serious Impact on Public Welfare: Granting the injunction must not risk causing serious adverse effects on public welfare (公共の福祉に重大な影響を及ぼすおそれがないこと).

The Tokyo High Court Decision (April 13, 2022): A Case Study

The practical difficulty of meeting these criteria, especially the "likelihood of success on the merits," was highlighted in the Tokyo High Court decision of April 13, 2022.

- Background: The case involved a company selling products claimed to remove or disinfect viruses and bacteria floating in indoor spaces using chlorine dioxide gas. The CAA demanded reasonable grounds to substantiate these claims (made on packaging, websites, and video ads). The company submitted various materials, including expert hearing records, peer-reviewed academic papers, external third-party test reports, and internal test reports. Dissatisfied, the CAA notified the company of its intention to issue a sochi meirei. The company filed a lawsuit seeking to prevent the order and simultaneously applied for a preliminary injunction under ACLA Article 37-5.

- District Court's Initial Ruling: The Tokyo District Court initially granted a partial preliminary injunction, temporarily halting the sochi meirei for two specific products (excluding claims of "99.9%" removal), finding that the submitted data might constitute reasonable grounds for general spatial disinfection claims in actual living environments, considering the difficulty of perfectly replicating all real-world conditions in tests.

- High Court's Reversal: Both the company and the State (representing the CAA) filed immediate appeals. The Tokyo High Court overturned the District Court's decision and denied the preliminary injunction entirely. Its reasoning focused heavily on the inadequacy of the "reasonable grounds" submitted, thus failing the "likelihood of success on the merits" requirement.

- Assessment of "Reasonable Grounds": The High Court meticulously evaluated the evidence based on the CAA's two criteria:

- Objective Verification: The court deemed the expert hearing records insufficient as they lacked objective, concrete supporting data. Crucially, it found the company's internal test reports, although conducted in actual residential rooms, were not "objectively verified." The court questioned the scientific rationale for certain test conditions (e.g., measurement timing, lack of testing under low humidity known to affect chlorine dioxide efficacy) and concluded these tests did not meet the standard of being conducted by methods generally accepted or deemed reasonable based on social norms and empirical rules. While the peer-reviewed papers and external test reports (conducted in closed laboratory chambers) were considered objectively verified regarding effects under specific test conditions, they faced issues with the second criterion.

- Appropriate Correspondence: The High Court found a fatal disconnect between the evidence and the advertising claims. The objectively verified external tests only demonstrated effects in sealed, controlled laboratory environments. They did not, in the court's view, provide reasonable grounds to substantiate claims of effectiveness in the vastly different conditions of actual living spaces (実生活空間 - jisseikatsu kūkan), which are not sealed and are subject to ventilation and other variables. Therefore, the submitted data failed to "appropriately correspond" to the broad claims being made to consumers.

- Interpretation of Claims and Disclaimers: The High Court also considered how consumers would interpret claims like "instantaneously" and "99.9%" removal/disinfection. It determined that, from the perspective of an average consumer lacking specialized knowledge, the overall impression created by the advertising (including visuals) implied rapid and near-complete effectiveness in typical indoor environments. The court found that accompanying disclaimers (打消し表示 - uchikeshi hyōji), such as mentioning that the "99.9%" figure was based on a 180-minute test in a closed 6-tatami-mat equivalent space, were insufficient to correct this primary impression, deeming them difficult for consumers to immediately and correctly understand. Research by the CAA has indeed shown that consumers often overlook or fail to comprehend the limitations mentioned in fine-print disclaimers, especially when accompanying strong positive claims.

- Assessment of "Reasonable Grounds": The High Court meticulously evaluated the evidence based on the CAA's two criteria:

- Conclusion on Likelihood of Success: Because the submitted data failed to provide reasonable grounds for the claims as interpreted by the court (effectiveness in actual living spaces), the High Court concluded that the company's main lawsuit challenging the CAA's assessment was unlikely to succeed. Without a likelihood of success on the merits, the preliminary injunction could not be granted.

Key Takeaways for Businesses Marketing in Japan

This case, and the underlying principles of the AUPMR and ACLA, offer critical lessons for U.S. and other international companies advertising in Japan:

- High Bar for Substantiation: Claims related to product performance, efficacy, or advantageous terms require robust, objective evidence before they are made. The burden under the AUPMR's Article 7(2) essentially requires advertisers to have their proof ready.

- Testing Must Match Claims: Perhaps the most crucial lesson from the High Court decision is the emphasis on "appropriate correspondence." Testing conducted under laboratory conditions may not be sufficient to support claims about real-world performance. If advertising implies effectiveness in typical consumer usage environments, the substantiating data must reflect testing under conditions relevant to those environments, or the claims must be carefully qualified.

- Objective Verification is Key: Internal testing data may be scrutinized heavily for objectivity and methodological rigor. Relying on independent, third-party testing using recognized industry or academic standards is generally advisable.

- Disclaimers Have Limited Power: Fine-print disclaimers or qualifications are unlikely to save an otherwise misleading headline claim, especially if they are inconspicuous or difficult for average consumers to understand. The overall impression created by the advertisement is paramount.

- Preliminary Injunctions are Difficult to Obtain: Seeking a preliminary injunction to stop a CAA order under the AUPMR is an uphill battle. Proving a likelihood of success on the merits is particularly challenging when the core issue is the sufficiency of the "reasonable grounds" already deemed inadequate by the agency. Courts tend to give deference to the specialized agency's initial assessment unless clear errors in law or fact are apparent at the preliminary stage.

- Proactive Compliance: The most effective strategy is proactive compliance. Rigorously review all advertising claims and marketing materials for clarity, accuracy, and, most importantly, ensure that robust, relevant, and objectively verifiable substantiation exists before launching any campaign in the Japanese market.

Conclusion

Japan's regulatory framework for advertising, enforced by the Consumer Affairs Agency under the AUPMR, places a significant emphasis on preventing misleading representations. The "reasonable grounds" requirement for performance claims, coupled with the CAA's authority to demand substantiation, creates a demanding environment for advertisers. As the Tokyo High Court's 2022 decision illustrates, challenging CAA actions through interim measures like preliminary injunctions faces considerable legal obstacles, particularly concerning the adequacy of evidence supporting advertising claims in real-world contexts. For businesses marketing products or services in Japan, careful attention to claim substantiation, testing methodology that reflects actual usage, clear and unambiguous communication, and proactive legal review are essential to navigate the regulatory landscape successfully and avoid potentially damaging administrative orders.

- Japan, US, and EU Advertising Regulation: A Comparative Look at Japan's Keihyōhō

- Key Changes in Japan's 2023 Premiums and Representations Act Revision

- How Does Japan's Servicer Law Regulate Advertising by Servicer Companies?

- Consumer Affairs Agency – AUPMR portal

- CAA Guidelines for Article 7(2) substantiation