Liability for False Financial Disclosure in Japan: Investor Remedies Under FIEA & Tort Law

TL;DR

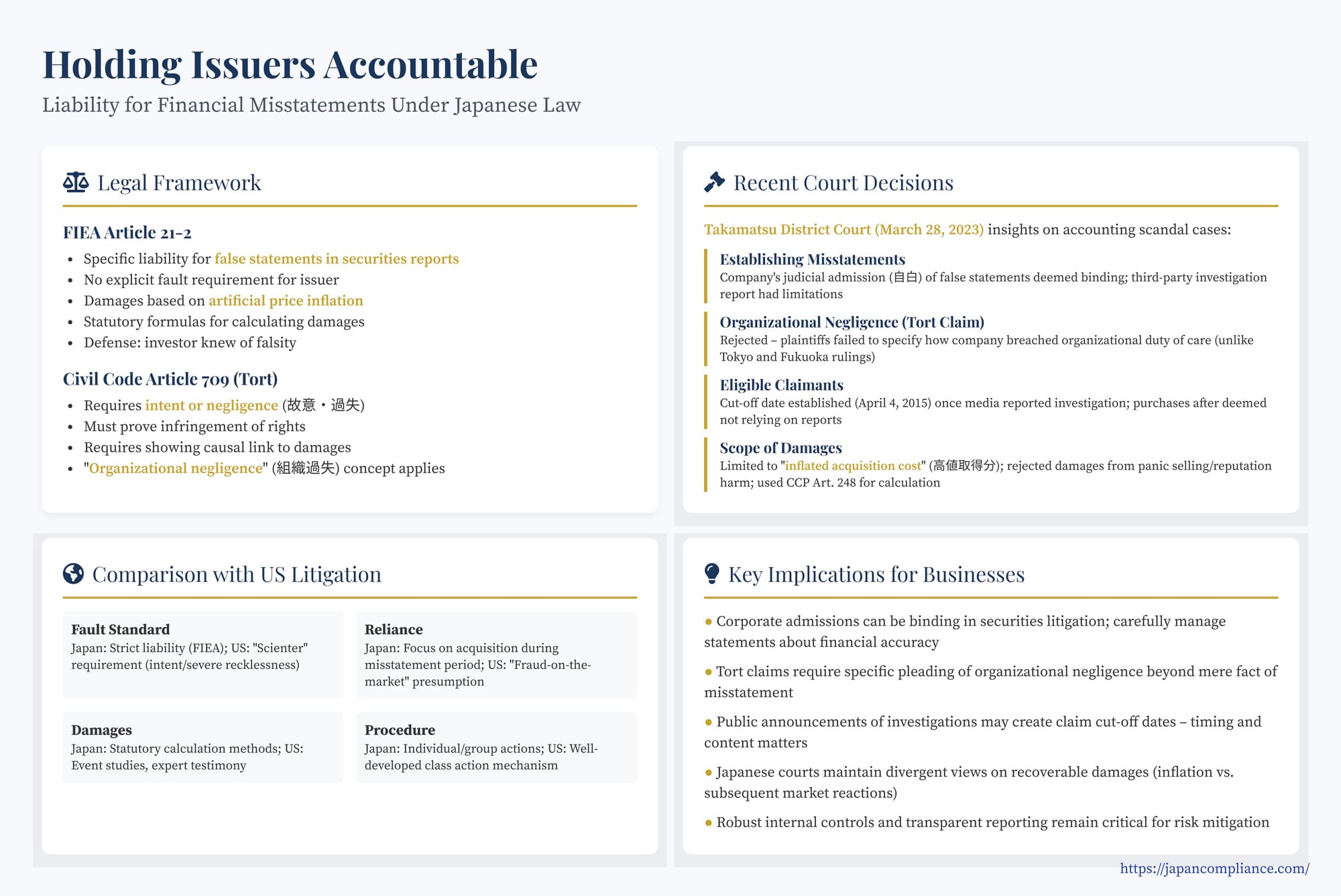

- Japan grants investors two main legal paths when listed firms misstate accounts: strict issuer liability under FIEA Art. 21-2 and fault-based tort claims (Civil Code 709).

- Recent litigation after the 2015 accounting scandal clarifies: corporate admissions can seal FIEA liability; organizational negligence must be pleaded with concrete control-failure facts; and damages are largely limited to the inflated purchase price, not post-scandal “panic-selling” losses in some courts.

- Acquisition timing matters: buy after the market learns of possible misstatements and you may lose standing.

Table of Contents

- Legal Framework for Issuer Liability

- FIEA Article 21-2 Explained

- Tort Claims & Organizational Negligence

- Recent Court Trends (Tokyo, Fukuoka, Takamatsu)

- Damage Theories and Calculation Methods

- Comparison with U.S. Rule 10b-5 Actions

- Practical Takeaways for Issuers and Investors

Accurate and reliable financial reporting by listed companies is fundamental to the integrity of capital markets. When corporations release inaccurate information, whether intentionally or negligently, investors who rely on that information can suffer significant losses. High-profile accounting scandals, such as the one involving a major Japanese industrial and electronics conglomerate revealed in 2015, underscore the importance of robust legal mechanisms for holding issuers accountable and providing redress for harmed investors.

In Japan, investor claims arising from misstatements in securities reports typically proceed under two main legal avenues: specific provisions within the Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) and general tort principles under the Civil Code. Recent court decisions, particularly those stemming from the aforementioned accounting scandal, have shed light on how Japanese courts apply these frameworks, clarifying key issues regarding liability standards, eligible claimants, and the scope of recoverable damages. This article explores the legal landscape of issuer liability for financial misstatements in Japan, drawing insights from these developments.

The Legal Framework for Issuer Liability

When investors suffer losses due to reliance on false or misleading information in a company's legally mandated disclosures (such as annual securities reports - 有価証券報告書, yūka shōken hōkokusho), they primarily look to two statutes for potential claims against the issuing company:

- Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) - Article 21-2 (金融商品取引法 第21条の2)

This provision specifically addresses the civil liability of issuers for damages suffered by investors who acquired securities based on disclosure documents containing material misstatements or omissions of material fact. Key aspects include:- Scope: It applies to core continuous disclosure documents like annual securities reports, quarterly reports, etc.

- Basis of Liability: The issuer is liable if there was a "false statement on important matters" (重要な事項についての虚偽の記載) or an omission of necessary important matters or facts needed to avoid misunderstanding.

- Claimants: Persons who acquired the relevant securities (typically in the secondary market) during the period the false statement was public.

- Damages: The FIEA provides specific methods for calculating damages, generally aimed at compensating for the artificial inflation in the purchase price caused by the misstatement. Article 21-2, paragraph 2 offers a formula based on the difference between the average market price in the month of acquisition and the average market price in the month after the correction was announced. Paragraph 3 provides a presumption based on the price drop following the announcement of the correction.

- Causation/Reliance: While not explicitly requiring proof of individual reliance in the same way as US law, the structure implies a connection between the misstatement and the investor's acquisition decision and subsequent loss. Causation regarding the amount of damages is often presumed or calculated based on the statutory formulas.

- Issuer Defenses: The issuer can avoid liability if it proves the claimant knew of the falsity at the time of acquisition (Art. 21-2(1) proviso). While related provisions concerning prospectuses (Art. 18, 19) or liability of officers (Art. 24-4) involve considerations of intent or negligence, Article 21-2 imposes a relatively strict liability standard directly on the issuing company itself for its continuous disclosure documents. The focus is less on the issuer's state of mind and more on the inaccuracy of the disclosure and the resulting investor harm.

- Civil Code - Article 709 (General Tort) (民法 第709条)

Beyond the specific FIEA provision, investors can also bring claims under general tort law. To succeed under Article 709, a plaintiff must establish:- Intent or Negligence (故意・過失): The issuer (acting through its representatives or employees) acted intentionally or negligently in making the misstatement.

- Infringement of Rights: The misstatement infringed the plaintiff's rights (typically causing financial loss).

- Damages: The plaintiff suffered quantifiable damages.

- Causation (因果関係): A causal link exists between the negligent/intentional misstatement and the damages suffered.

- "Organizational Negligence" (組織過失, soshiki kashitsu): Establishing negligence by specific individuals within a large corporation can be difficult. Japanese courts have sometimes recognized the concept of "organizational negligence," where liability can be imposed on the company itself if systemic failures in its organizational activities (e.g., internal controls, reporting structures) led to the tortious outcome (the misstatement), even without pinpointing specific individual fault.

Comparing FIEA and Tort Claims:

The FIEA claim under Article 21-2 offers advantages like a potentially stricter liability standard for the issuer and statutory damage calculation methods, simplifying proof for investors. However, its application is tied to specific disclosure documents and acquisition timing. A general tort claim under Article 709 is broader in potential application but requires proof of fault (intent or negligence), which can be challenging, although the concept of organizational negligence offers a potential path. Damage calculations under tort law might theoretically be broader but lack the FIEA's presumptions. Often, plaintiffs plead both in the alternative.

Insights from Recent Court Decisions

A series of lawsuits filed by investors against the major conglomerate involved in the 2015 accounting scandal has led to several court decisions, primarily at the district and high court levels. These rulings provide valuable insights into how the legal framework is applied in practice. A notable decision from the Takamatsu District Court (March 28, Reiwa 5 - 2023), among others, addressed several critical points:

1. Establishing the Existence of Misstatements:

Proving that a financial statement contained material misstatements is the first hurdle. In the Takamatsu case, the plaintiffs relied heavily on the findings of a third-party investigation report commissioned by the company itself. The court noted potential weaknesses in the plaintiffs' specific allegations, suggesting they didn't go much beyond citing the report. However, the company itself admitted (自白, jihaku) in court that its past securities reports for certain fiscal years contained "false statements on important matters," while disputing the falsity of some specific corrected amounts. The court gave significant weight to this admission by the company, deeming it a judicial admission binding on the court for the admitted portions, thus establishing the FIEA Art. 21-2 violation for those parts. This contrasts slightly with an earlier Tokyo District Court decision (May 13, Reiwa 3 - 2021, involving institutional investors) which more directly relied on the investigation report to find misstatements, a finding some commentators felt was insufficiently detailed given the complexities of the accounting issues involved. The Takamatsu approach highlights the strategic importance of judicial admissions in complex securities litigation.

2. Proving Corporate Negligence (Organizational Negligence):

While finding liability under FIEA Art. 21-2 based on the admission, the Takamatsu court rejected the plaintiffs' parallel claim under Civil Code Art. 709 (tort). The court reasoned that the plaintiffs failed to provide specific allegations detailing how the company, as an organization, breached its duty of care. Merely stating that misstatements occurred was insufficient; the plaintiffs needed to articulate, with a certain degree of specificity, what preventative measures the company should have taken within its organizational structure and processes, how it failed to do so, and how fulfilling that duty could have prevented the false statements.

This denial of the tort claim stands in contrast to the Tokyo District Court decision (May 13, 2021) and a Fukuoka District Court decision (March 10, Reiwa 4 - 2022), both of which did find the company liable under Article 709 based on organizational negligence. Commentators noted that finding organizational negligence based merely on the fact that the securities reports were prepared organizationally, as arguably occurred in the Fukuoka case, might risk creating de facto strict liability under tort law, potentially conflicting with the fault-based principles underlying Article 709 and blurring the lines with the distinct liability regime of FIEA Art. 21-2. The Takamatsu decision emphasizes the need for plaintiffs pursuing tort claims to articulate a concrete theory of organizational failure.

3. Eligible Claimants and Relevant Timeframe:

FIEA Article 21-2 links liability to the act of acquiring securities based on flawed disclosures. Consequently, the Takamatsu court confirmed that shares acquired before the first filing of a misleading securities report were not eligible for damages under this provision.

More significantly, the court established a cutoff date for eligible acquisitions. The company publicly announced the establishment of a special investigation committee regarding accounting irregularities on April 3, Heisei 27 (2015). The court held that by the following day, April 4, 2015, general investors were, or should have been, aware of potential inaccuracies in the company's past financial reports due to media coverage. Therefore, investors who acquired shares on or after April 4, 2015, were deemed unable to claim reliance on the veracity of those past reports. The court applied the logic of the FIEA Art. 21-2(1) proviso (claimant's knowledge of falsity) by analogy, effectively barring claims for shares purchased after the widespread dissemination of news casting doubt on the financials. This established a clear, albeit potentially harsh for some later purchasers, temporal boundary for claims based on reliance on the pre-scandal reports.

4. Scope and Calculation of Damages:

This area saw significant divergence between the Takamatsu decision and other related rulings.

- Compensable Harm: The Takamatsu court interpreted "damages" under FIEA Art. 21-2 as encompassing all losses with adequate causation to the misstatement. It readily accepted that investors who paid an artificially inflated price due to the misstatement suffered compensable harm – the difference between the price paid and the hypothetical market price absent the misstatement (the "inflated acquisition cost" or 高値取得分, takane shutokubun).

- Rejection of Panic Selling / Reputational Harm: Crucially, the court rejected the plaintiffs' claims for additional damages stemming from the general stock price decline caused by factors like damage to the company's reputation or subsequent panic selling (ろうばい売り, rōbai uri) after the scandal broke. The court reasoned that shareholders inherently bear the risk of stock price fluctuations tied to the company's fortunes and reputation. For those who acquired shares before the specific misleading reports were filed, these later losses were simply part of share ownership risk. For those who acquired shares based on the misleading reports (and thus fell under FIEA 21-2), the court found insufficient legal causation between the misstatement itself and these subsequent market-wide declines driven by reputational damage or panic. It viewed such losses as not directly flowing from the act of purchasing at an inflated price due to the specific false statement, distinguishing them from the takane shutokubun. This interpretation is notably stricter than the Tokyo (May 13, 2021) and Fukuoka (March 10, 2022) decisions, which did allow damages encompassing losses from panic selling and reputational harm, arguably aligning more closely with a Supreme Court precedent (March 13, Heisei 24 - 2012) suggesting FIEA damages aren't strictly limited to the acquisition price difference.

- Damage Calculation Method (Art. 248): In the Takamatsu case, the plaintiffs did not invoke the specific damage calculation presumptions provided in FIEA Art. 21-2(3). Acknowledging the inherent difficulty in precisely proving the hypothetical "true" stock price absent the misstatement, the court applied Article 248 of the Code of Civil Procedure. This provision allows a court, when the nature of the damage makes precise proof extremely difficult, to determine a reasonable amount of damages based on the overall arguments and evidence. The court used this to quantify the takane shutokubun. This application of Art. 248 is noteworthy because the Tokyo decision (May 13, 2021), which also found liability under FIEA 21-2, had explicitly rejected using Art. 248, reasoning that the existence of the specific damage presumptions within FIEA Art. 21-2 precluded resort to the general procedural provision. The Takamatsu court appears to take the view that if plaintiffs choose not to rely on the FIEA presumptions, Art. 248 remains available.

Comparison with US Securities Litigation

While sharing the goal of investor protection, the Japanese approach to issuer liability exhibits key differences from US securities litigation, particularly class actions under SEC Rule 10b-5:

- Fault Standard: While FIEA Art. 21-2 imposes relatively strict liability on the issuer, US Rule 10b-5 requires plaintiffs to prove "scienter" – intent to deceive, manipulate, or defraud, or severe recklessness. Tort claims in Japan require negligence or intent.

- Reliance: US law utilizes the "fraud-on-the-market" theory, creating a rebuttable presumption of reliance for investors trading in efficient markets. Japanese law under FIEA 21-2 doesn't explicitly require individual reliance proof in the same manner, focusing more on the acquisition occurring during the period of misrepresentation, though claimant knowledge is a defense. The recent court decisions establishing cutoff dates based on public awareness serve a somewhat analogous function in limiting claims based on presumed reliance.

- Loss Causation: US law requires plaintiffs to demonstrate that the disclosure of the truth (the correction of the misstatement) caused their economic loss. The Japanese FIEA focuses more directly on the damage calculation formulas tied to acquisition and correction dates. The Takamatsu court's rejection of damages for panic selling highlights a potentially narrower view of recoverable losses compared to what might be argued under US loss causation principles.

- Damages: FIEA provides specific calculation methods and presumptions. US damage calculations often involve event studies and expert testimony to estimate the artificial inflation removed from the stock price upon corrective disclosure, potentially leading to different quantum assessments.

- Procedure: The US features a highly developed class action mechanism for securities fraud. While Japan has introduced limited collective action procedures, large-scale securities class actions comparable to the US model are less common; investor claims are often pursued through individual lawsuits or coordinated group actions. Discovery processes also differ significantly, being generally more limited in Japan.

Conclusion

The legal framework in Japan provides avenues for investors harmed by financial misstatements through both the specific provisions of the FIEA (Art. 21-2) and general tort law (Civil Code Art. 709). Recent litigation involving a major accounting scandal has tested and clarified the application of these laws. Key takeaways include the potential binding effect of corporate admissions regarding misstatements, the specific requirements for pleading organizational negligence under tort law, the establishment of clear timeframes for eligible claims based on public awareness of potential issues, and ongoing judicial debate regarding the precise scope of recoverable damages under the FIEA, particularly concerning losses beyond the initial price inflation.

The Takamatsu District Court's decision, while aligning with others on FIEA liability based on admissions, offers a more conservative interpretation regarding organizational negligence and the scope of recoverable damages compared to some other rulings on the same underlying scandal. This highlights that the jurisprudence in this complex area is still evolving. For businesses operating in Japan's capital markets, these developments underscore the critical importance of robust internal controls, transparent financial reporting, and a clear understanding of the potential legal consequences should inaccuracies arise.