Hiring in Japan: Fixed-Term & Post-Retirement Workers—Avoiding “Unreasonable Disparity” Claims

TL;DR

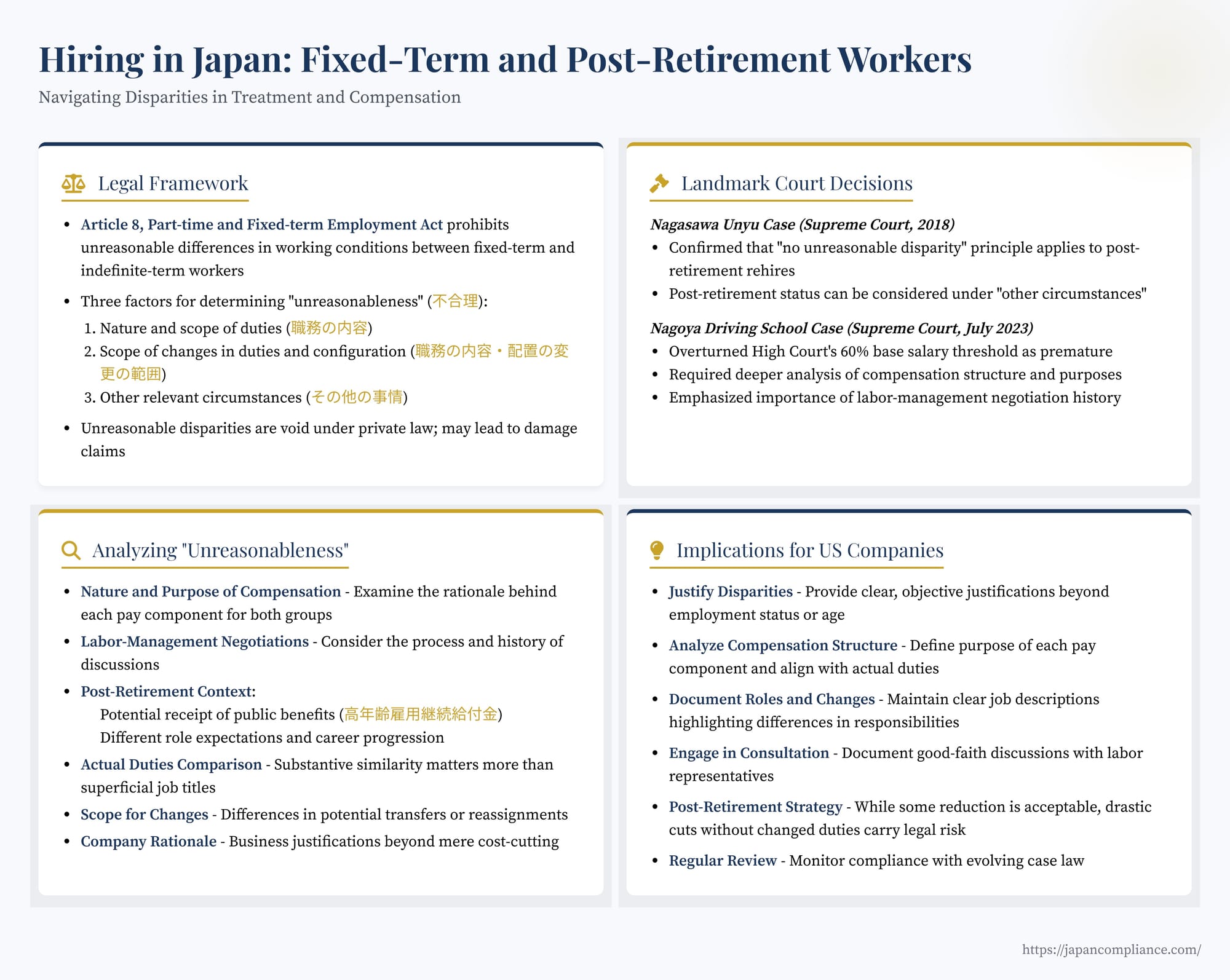

- Japan’s Part-Time & Fixed-Term Employment Act bars “unreasonable disparities” in pay and benefits versus comparable regular staff.

- Supreme Court precedent (Nagasawa 2018; Nagoya Driving School 2023) shows courts will dissect each pay component and negotiation history—simple percentage cuts post-retirement are risky.

- Employers must document duty differences, compensation rationale and labour-management talks, or face back-pay suits under Civil Code 709.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Framework: Prohibiting Unreasonable Disparities

- Post-Retirement Reemployment: A Complex Application

- The Nagoya Driving School Case (Supreme Court, 20 July 2023)

- Analyzing “Unreasonableness”: Key Factors Post-Nagoya

- Implications for US Companies in Japan

- Conclusion

Japan's labor market is characterized by distinct employment structures, including a significant number of non-regular workers employed on fixed-term contracts or re-hired after mandatory retirement. This demographic trend, coupled with an aging workforce and evolving work styles, presents unique legal challenges for employers, particularly concerning compensation and working conditions compared to their permanent, indefinite-term counterparts. A core principle in Japanese labor law prohibits "unreasonable disparities" in treatment based solely on employment status. Understanding how this principle applies, especially in the complex context of post-retirement reemployment, is crucial for companies operating in Japan, as highlighted by recent key court decisions.

The Legal Framework: Prohibiting Unreasonable Disparities

The central tenet governing the fair treatment of non-regular employees stems originally from Article 20 of the Labor Contracts Act (LCA - 労働契約法, Rōdō Keiyaku-hō). This provision, now superseded but substantively carried over into Article 8 of the Act on Improvement of Personnel Management and Conversion of Employment Status for Part-Time Workers and Fixed-Term Workers (Part-time and Fixed-term Employment Act - パートタイム・有期雇用労働法, Pāto Taimu Yūki Koyō Rōdō-hō), prohibits establishing working conditions for fixed-term or part-time workers that are unreasonably different from those of comparable indefinite-term workers employed by the same employer, simply because their employment contract has a fixed term or they work part-time.

The law aims to protect these workers, who may be in weaker bargaining positions or face anxieties about contract renewal ("雇止め" - yatoidome), from unfair treatment. The prohibition covers all working conditions, including not only base salary, bonuses, and allowances, but also benefits like leave, education and training opportunities, welfare facilities, and safety management.

To determine whether a difference in treatment is "unreasonable" (不合理 - fugōri), the law mandates consideration of three key factors:

- Nature and Scope of Duties (職務の内容 - shokumu no naiyō): This involves comparing the actual job responsibilities, tasks performed, and the level of authority or accountability associated with the roles of the fixed-term/part-time worker and the comparable indefinite-term worker.

- Scope of Changes in Duties and Configuration (当該職務の内容及び配置の変更の範囲 - tōgai shokumu no naiyō oyobi haichi no henkō no han'i): This factor considers the extent to which the job duties, responsibilities, and work locations are expected to change over the course of employment, including the potential for transfers or reassignments. Typically, indefinite-term employees may have broader potential scopes for change compared to fixed-term employees hired for specific projects or roles.

- Other Circumstances (その他の事情 - sono ta no jijō): This is a catch-all category allowing consideration of various relevant factors specific to the case. This can include the company's operational practices, the purpose behind specific allowances or benefits, the history and outcomes of labor-management negotiations regarding working conditions, and, particularly relevant in post-retirement cases, factors unique to reemployment after mandatory retirement.

If a disparity is found to be unreasonable under this analysis, the specific contractual provision creating that disparity is deemed void under private law. While this doesn't automatically grant the non-regular worker the exact same conditions as the regular worker, it can form the basis for damage claims (often calculated as the difference between the actual condition and what would have been reasonable, potentially mirroring the regular employee's condition) under tort law (Civil Code Article 709) if the employer acted negligently or intentionally.

Post-Retirement Reemployment: A Complex Application

A particularly complex area involves applying this "no unreasonable disparity" principle to employees re-hired on fixed-term contracts after reaching the company's mandatory retirement age (定年 - teinen, commonly 60 or 65). It's a widespread practice in Japan for companies to re-employ retired workers, often in similar roles but typically at significantly reduced salaries and benefits, under systems known as kōreisha saikoyō seido (高齢者再雇用制度).

The legality of these wage reductions has been tested in court. The landmark Nagasawa Unyu Case (Supreme Court, June 1, 2018) established that the principle (then LCA Article 20) does apply to post-retirement rehires. However, the Court also ruled that the specific circumstances of being a re-hired retiree can be considered under "other circumstances." This includes factors like the potential availability of public pensions and employment continuation benefits (see below), the often-reduced expectation of career progression or assumption of managerial roles post-retirement, and the specific agreements reached regarding post-retirement work. In Nagasawa Unyu, the Supreme Court found disparities in certain allowances (like perfect attendance allowance) to be unreasonable, but upheld differences in base salary, bonuses, and certain other allowances, acknowledging the distinct context of post-retirement employment.

This set the stage for further litigation exploring how much of a difference is acceptable, particularly regarding core compensation elements like base salary and bonuses.

The Nagoya Driving School Case (Supreme Court, July 20, 2023)

A recent key development came with the Supreme Court's decision in a case involving driving school instructors (commonly referred to as the Nagoya Driving School Case - 名古屋自動車学校事件, Nagoya Jidōsha Gakkō Jiken, decided July 20, 2023).

- Facts: Two driving instructors were re-hired as "shokutaku" (嘱託) or contract employees on one-year fixed-term contracts after reaching the mandatory retirement age of 60. Their job duties and scope of potential changes remained largely the same as before retirement. However, their base salaries were drastically reduced – to less than 50% of their pre-retirement base pay after the first year. Their bonuses were also significantly lower. The instructors sued, arguing this disparity violated the principle against unreasonable differences (then LCA Article 20).

- Lower Court Rulings: The District Court and the Nagoya High Court found the disparities partially unreasonable. The High Court ruled that reducing the base salary below 60% of the pre-retirement level was illegal, ordering the company to pay the difference. It reasoned that the employees' duties hadn't changed significantly and considered other factors like the lack of specific labor-management agreement justifying the gap.

- Supreme Court Decision: The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for reconsideration. It did not rule that the wage reduction was necessarily reasonable, but found that the High Court's analysis was insufficient.

- Supreme Court's Reasoning: The key points emphasized by the Supreme Court were:

- Insufficient Analysis of Compensation Nature/Purpose: The High Court failed to thoroughly examine the nature and purpose of the base salary and bonuses for both the regular employees (before retirement) and the re-hired contract employees. Was the regular employees' base pay purely based on seniority (nenkōkyū)? Did it include elements reflecting job duties (shokumukyū) or skills/abilities (shokunōkyū)? Was the reduced base pay for re-hired employees intended to reflect different expectations or roles, even if duties seemed similar on the surface? The Court stated that simply observing a difference wasn't enough; the rationale and function of each pay component needed scrutiny before declaring a difference unreasonable. The Court noted, for instance, that the base pay for re-hired employees might have a different nature or purpose (e.g., not expecting promotion, different calculation basis) than that for regular employees.

- Insufficient Consideration of Labor-Management Negotiations: While the High Court noted the absence of an explicit agreement justifying the pay cut, the Supreme Court stated that the analysis of "other circumstances" requires looking deeper into the specific process and history of any labor-management negotiations regarding the working conditions for re-hired employees. Simply noting the outcome (or lack thereof) wasn't enough; the exchanges, proposals, and responses during any relevant discussions should have been considered.

- Need for Re-evaluation: Given these analytical shortcomings regarding the nature of compensation and the negotiation history, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's finding of unreasonableness (specifically the 60% threshold) was premature and lacked sufficient basis. The case was sent back for a more detailed examination of these factors.

Analyzing "Unreasonableness": Key Factors Post-Nagoya

The Nagoya Driving School ruling doesn't provide a simple percentage threshold for acceptable post-retirement wage cuts. Instead, it reinforces a multi-faceted analysis, demanding a deeper dive into the justification for any disparities. Based on this ruling and related case law, the key considerations in assessing the reasonableness of differences in working conditions (especially pay) between regular employees and fixed-term/post-retirement hires are:

- Nature and Scope of Duties: This remains fundamental. Are the tasks, responsibilities, workload, and required skills genuinely comparable? If duties are significantly lighter or less complex post-retirement, a corresponding difference in pay is more likely to be considered reasonable. Superficial similarity is not enough; the substance matters.

- Scope of Changes: Is the fixed-term/re-hired employee expected to undergo the same range of potential transfers, reassignments, or career development paths as a comparable regular employee? Limited scope for change can sometimes justify differences in base pay structures designed to reward long-term development within the company.

- Other Circumstances: This requires careful evaluation:

- Nature and Purpose of Each Compensation Component: As emphasized in the Nagoya case, employers must be able to articulate the specific purpose of each pay element (base salary, allowances, bonuses). Is base pay linked to seniority, job complexity, skills, or performance? Is a bonus purely performance-based, or does it reflect expected future contributions? Are allowances tied to specific duties or expenses? A clear rationale is needed if components differ between employment categories despite similar work. Relying vaguely on "seniority" for regular staff while paying significantly less for similar post-retirement work is risky if the underlying job value seems comparable.

- Labor-Management Negotiation History: Evidence of good-faith discussions and agreements (or lack thereof) with unions or employee representatives regarding the terms for non-regular or re-hired employees can be a significant factor.

- Post-Retirement Context (Nagasawa Factors): The fact that an employee is re-hired post-retirement remains a relevant circumstance. This can include:

- Potential Receipt of Public Benefits: Re-hired employees aged 60-65 may be eligible for public pensions (like Rōrei Kōsei Nenkin) and/or High-Age Employment Continuation Basic Benefit (Kōnenrei Koyō Keizoku Kihon Kyūfukin - a benefit from the employment insurance system paid when wages drop significantly after age 60, though this benefit is scheduled to be reduced from April 2025 and potentially abolished later). Some court decisions and legal commentary suggest that the employee's overall financial situation, including these benefits, might be considered as part of the "other circumstances" justifying a lower company wage. However, the extent to which employers can explicitly rely on public benefits to justify wage cuts remains legally debated and potentially problematic. The Supreme Court in Nagoya did not explicitly endorse this factor.

- Different Role Expectations: Often, post-retirement roles, even if involving similar tasks, may come with reduced expectations regarding managerial responsibilities, training junior staff, or long-term career progression.

- Company Rationale and Operational Needs: The employer's specific business reasons for the pay structure and any demonstrated operational requirements can be considered, although mere cost-cutting without other justifications is unlikely to suffice.

- Absolute Wage Levels: While relative disparity is the focus, some lower court decisions (like the Nagoya High Court) have also considered whether the reduced wage itself falls below a certain standard (e.g., compared to industry benchmarks or even younger regular employees) as an indicator of potential unreasonableness.

Implications for US Companies in Japan

The evolving case law surrounding fixed-term and post-retirement employment conditions carries significant implications for US companies employing staff in Japan:

- Justify Disparities: Companies must be prepared to provide clear, objective justifications for any significant differences in compensation or benefits between regular employees and non-regular employees (fixed-term or post-retirement rehires) performing comparable work. Relying solely on employment status or age is legally insufficient and risky.

- Analyze Compensation Structures: Carefully define the purpose and rationale behind each component of the compensation package (base salary, bonuses, various allowances). Ensure the structure aligns with the actual duties, responsibilities, and expectations for different employee categories. Avoid base pay systems that rely heavily on seniority for regular staff if fixed-term/re-hired staff perform similar roles without a clear justification for the difference.

- Document Roles and Changes: Maintain clear job descriptions outlining duties and responsibilities. If post-retirement roles involve reduced responsibilities or expectations compared to pre-retirement roles, document these differences explicitly.

- Consultation and Negotiation: Where applicable (e.g., if dealing with a labor union), engage in good-faith discussions regarding the terms and conditions for non-regular employees, including post-retirement hires. Documenting this process can be valuable.

- Post-Retirement Pay Strategy: Designing post-retirement compensation requires careful consideration. While some wage reduction is generally accepted by courts acknowledging the context (including potential access to pensions/benefits), drastic cuts without clear changes in duties or responsibilities carry significant legal risk. Setting wages below a certain percentage (like the 60% mark tested in the Nagoya High Court, although rejected as a simple threshold by the Supreme Court) could attract legal challenges if not well-justified by other factors. Relying explicitly on public benefits to set company wages is legally uncertain.

- Risk Management: Regularly review compensation structures for non-regular employees to ensure compliance with the "no unreasonable disparity" principle and evolving case law. Unjustified disparities can lead to litigation seeking back pay and damages.

Conclusion

Japan's legal framework seeks to balance flexibility in employment with fairness for non-regular workers. The prohibition against unreasonable disparities, particularly as interpreted in the context of post-retirement reemployment highlighted by the Nagoya Driving School Supreme Court decision (July 20, 2023), underscores the need for employers to meticulously justify differences in working conditions. Companies cannot rely on broad assumptions about seniority or retirement status; they must analyze the specific nature and purpose of job roles and compensation components, alongside other relevant circumstances like negotiation history. For US companies employing fixed-term or post-retirement workers in Japan, a proactive approach involving careful job design, clearly defined compensation rationales, and documented justifications for any significant disparities is essential to navigate this complex legal terrain and mitigate litigation risks.

- Mind the Gap: Navigating Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees in Japan

- Post-Pandemic Japanese Labor Law: Dismissal, Relocation & Side-Job Pitfalls Explained

- Understanding Japan’s New Freelance Protection Act: What US Companies Need to Know

- MHLW – Q&A on Part-Time & Fixed-Term Employment Act (Japanese)

- MHLW – Guidelines on Post-Retirement Reemployment Systems (Japanese)