Hiding Income in Nominee Accounts: When Non-Filing Becomes Criminal Tax Evasion in Japan

Date of Decision: September 13, 1994

Case Name: Income Tax Act Violation Case (平成2年(あ)第1095号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

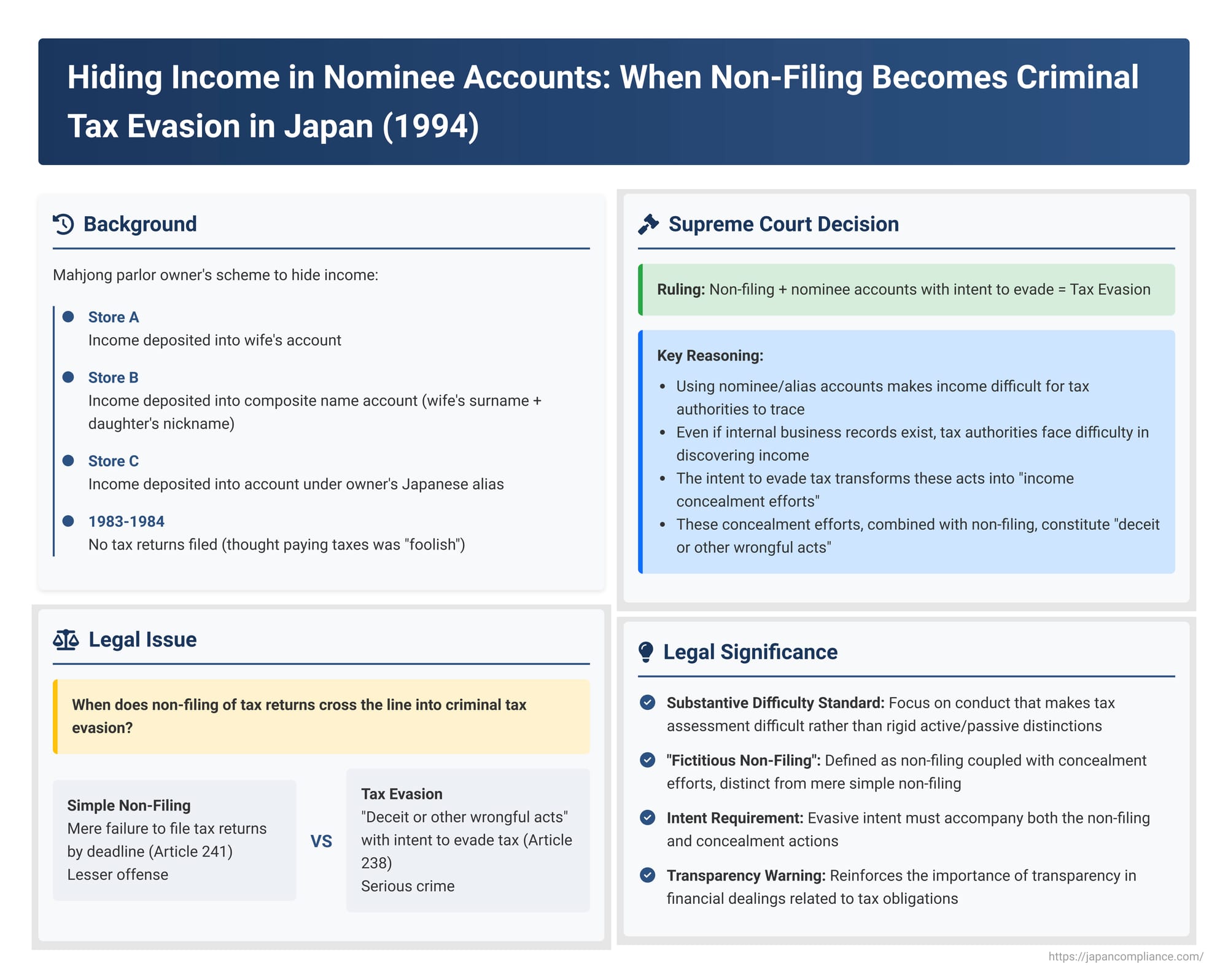

In a significant decision on September 13, 1994, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified the distinction between simple non-filing of an income tax return and the more serious crime of fraudulent tax evasion. The case involved a business owner who, in addition to not filing tax returns, systematically deposited business income into bank accounts held under nominee or alias names. The Court affirmed that such "income concealment efforts," when undertaken with the intent to evade tax and coupled with non-filing, constitute the "deceit or other wrongful acts" necessary for a conviction of tax evasion.

The Mahjong Parlor Owner's Scheme

The defendant, identified by his real name as A (anonymized from 甲 - Ko), was the operator of three mahjong parlors: Store A, Store B, and Store C. For his own business management purposes, A had the managers of each store accurately record their respective sales and expenditures in business ledgers.

However, when it came to handling the sales revenue, A employed a system designed to obscure his direct link to the income:

- Store A's Sales: Income from Store A was deposited into a bank account held in the name of A's wife, B (anonymized from 乙 - Otsu).

- Store B's Sales: Income from Store B was deposited into an account under a composite name, C (anonymized from 丙 - Hei). This name was formed by combining his wife's naturalized Japanese surname with his eldest daughter's Japanese nickname. (It was noted that when these accounts were later moved from Bank D to Bank E in March 1983, a store manager handling the transfer mistakenly wrote the given name part of "C" using different kanji characters with the same pronunciation, an error A became aware of but did not correct).

- Store C's Sales: Income from Store C was deposited into an account held under D (anonymized from 丁 - Tei), which was A's own commonly used Japanese alias.

Regarding his tax obligations, A had a history of under-compliance. Up until the 1982 tax year, he had filed income tax returns under the name "D (also known as A)," but these returns reported only a very small fraction of his actual income. Subsequently, A reportedly came to believe that filing and paying taxes was "foolish" (馬鹿馬鹿しい - bakabakarashii). Consequently, for the 1983 and 1984 tax years, A did not file any income tax returns at all, allowing the statutory filing deadlines to pass.

As a result, A was prosecuted for the crime of tax evasion under Article 238, paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act for the 1983 and 1984 tax years. In his defense, A argued that while he may have failed to file returns, his actions only constituted the lesser offense of "simple non-filing" under Article 241 of the Income Tax Act, and not the more severe crime of fraudulent tax evasion. The first instance court convicted A of tax evasion. The High Court upheld this conviction, reasoning that while the use of the alias D might not have been a false name per se, the use of his wife's name (B) for an account was a "borrowed name" (shakumei), and the composite name (C) was either a "false name" (kamei) or a borrowed name. The High Court found that setting up and using such bank accounts constituted "income concealment efforts" (shotoku hitoku kōsaku) and that A had the intention of using these efforts as a means to evade taxes. A then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Distinction: Simple Non-Filing vs. Fraudulent Tax Evasion

The core of the legal dispute lay in the distinction between two offenses under the Income Tax Act:

- Simple Non-Filing (単純不申告 - tanjun fushinkoku): Governed by Article 241 (at the time), this is generally a less severe offense that penalizes the mere failure to file a tax return by the statutory deadline without a justifiable reason.

- Tax Evasion (逋脱罪 - hodatsuzai): Defined in Article 238, paragraph 1, this is a more serious crime. It requires not only an underpayment or non-payment of tax but also that the taxpayer achieved this through "deceit or other wrongful acts" (偽りその他不正の行為 - itsuwari sonota fusei no kōi) with the intent to evade tax.

The Supreme Court had a line of precedents interpreting the meaning of "deceit or other wrongful acts":

- An early ruling in Showa 24 (1949) established that for tax evasion to be constituted, "active" fraudulent means were necessary; simple non-filing alone was insufficient.

- This was reaffirmed in two Showa 38 (1963) decisions, which held that even a non-filing done with the intent to evade tax would not amount to "wrongful acts" if it was merely a failure to file, without additional fraudulent conduct.

- A crucial development came with a Grand Bench decision in Showa 42 (1967) (the case from t123). This ruling refined the definition, stating that "deceit or other wrongful acts" means "with the intent to evade tax, employing as a means thereof some form of artifice or other contrivance that makes the assessment and collection of tax impossible or extremely difficult." This shifted the focus from the purely formal distinction of "active" versus "passive" conduct to the substantive impact of the taxpayer's actions in hindering tax authorities.

The question before the Supreme Court in A's case was whether his specific conduct—using nominee or alias bank accounts to receive business income, coupled with his complete failure to file tax returns for those years—crossed the line from simple non-filing into the realm of fraudulent tax evasion by constituting "income concealment efforts" that fit the definition of "deceit or other wrongful acts."

The Supreme Court's Decision: Nominee Accounts + Non-Filing = Tax Evasion

The Supreme Court dismissed A's appeal, thereby upholding his conviction for tax evasion. The Court's reasoning focused on the nature and effect of A's use of the nominee and alias bank accounts:

- High Court's Findings Recited: The Supreme Court noted the High Court's findings: A, with the intent to evade tax, had deposited a portion of his mahjong parlors' sales income into pre-existing bank accounts held under nominee or alias names, and then failed to file tax returns for his business income. It was also noted that A did have accurate internal business records prepared by his store managers for his own operational oversight and that there was no evidence he had actively concealed these internal books from tax authorities or created a separate set of false books for deception.

- Difficulty in Grasping Income, Despite Internal Books: The Supreme Court reasoned that even if a taxpayer maintains accurate internal records, there is no guarantee that tax authorities will be able to ascertain the contents of these books during a tax investigation. The mere existence of such books does not mean the income is readily discoverable by the authorities if it is otherwise obscured.

- Use of Nominee/Alias Accounts as an Act of Concealment: Therefore, the act of depositing sales income into bank accounts held under nominee or alias names is, in itself, an act that "makes it difficult for tax authorities to grasp the income" (税務当局による所得の把握を困難にさせる - zeimu tōkyoku ni yoru shotoku no haaku o konnan ni saseru).

- Intent to Evade as a Key Factor: If such actions (using nominee/alias accounts) are undertaken with the "intent to evade" tax (ほ脱の意思に出たもの - hodatsu no ishi ni deta mono), then these actions constitute "income concealment efforts" (shotoku hitoku kōsaku).

- The Combination Constitutes Tax Evasion: The Supreme Court concluded that an act of non-filing, when accompanied by such "income concealment efforts" undertaken with the intent to evade tax, satisfies the criteria for "deceit or other wrongful acts" and thus constitutes the crime of tax evasion under Article 238, paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act.

The Court found the High Court's judgment, which reached the same conclusion, to be correct.

Analysis and Implications

This 1994 Supreme Court decision provides important clarification on the line between simple non-filing and criminal tax evasion:

- Affirmation of the "Substantive Difficulty" Standard: The ruling is consistent with the Showa 42 (1967) Grand Bench decision by focusing on conduct that makes it difficult for tax authorities to discover and assess income, rather than relying on a rigid distinction between "active" commissions and "passive" omissions. The key is the effect of the taxpayer's actions in impeding tax administration.

- "Income Concealment Efforts" Clarified: The use of nominee or alias bank accounts, when coupled with an intent to evade tax, is now clearly identified as a form of "income concealment effort." Even if a taxpayer maintains accurate records for their own internal use, if they deliberately channel income through accounts designed to obscure its true ownership from the tax authorities, this can be a crucial element in establishing fraudulent evasion.

- "Fictitious Non-Filing" (Kyogi Fushinkoku): Legal commentators often categorize this type of conduct—where non-filing is coupled with positive acts of concealment—as "fictitious non-filing" or "deceptive non-filing." This is distinct from "simple non-filing" where no such active concealment efforts are present. Another Supreme Court decision from Showa 63 (1988) had similarly found tax evasion where a taxpayer recorded fictitious costs to hide income and then failed to file a return.

- The Role of "Intent to Evade" in Characterizing Concealment: The Supreme Court's emphasis that the use of nominee accounts, if done with the intent to evade tax, constitutes income concealment is significant. This highlights that the taxpayer's subjective state of mind (the intent to evade) is crucial in characterizing acts like using nominee accounts as part of a fraudulent scheme. The PDF commentary on this case suggests a nuanced point: if the primary actus reus (criminal act) of evasion in a non-filing scenario is the failure to file itself (as suggested by the Showa 63 precedent), then the "intent to evade" must accompany that non-filing. The "income concealment efforts" are then the "means" by which this evasion is facilitated. The current decision's phrasing ("if recognized as stemming from an intent to evade, it constitutes income concealment efforts") might imply that the evasive intent imbues the concealment acts themselves with a fraudulent character, making them part of the "wrongful acts," even if they don't meet the extremely high bar of making assessment "impossible or extremely difficult" on their own, as long as they do make it difficult to grasp income.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1994 decision in this case serves as a critical affirmation that the failure to file an income tax return, when combined with deliberate "income concealment efforts" such as the use of nominee or alias bank accounts undertaken with the intent to evade tax, can transcend the lesser offense of simple non-filing and constitute the more serious crime of fraudulent tax evasion. The ruling underscores that it is not merely the absence of a tax return, but the accompanying deceptive conduct aimed at making income difficult for tax authorities to detect and assess, that elevates the offense to the level of "deceit or other wrongful acts" required for an evasion conviction. This decision reinforces the importance of transparency in financial dealings as they relate to tax obligations.