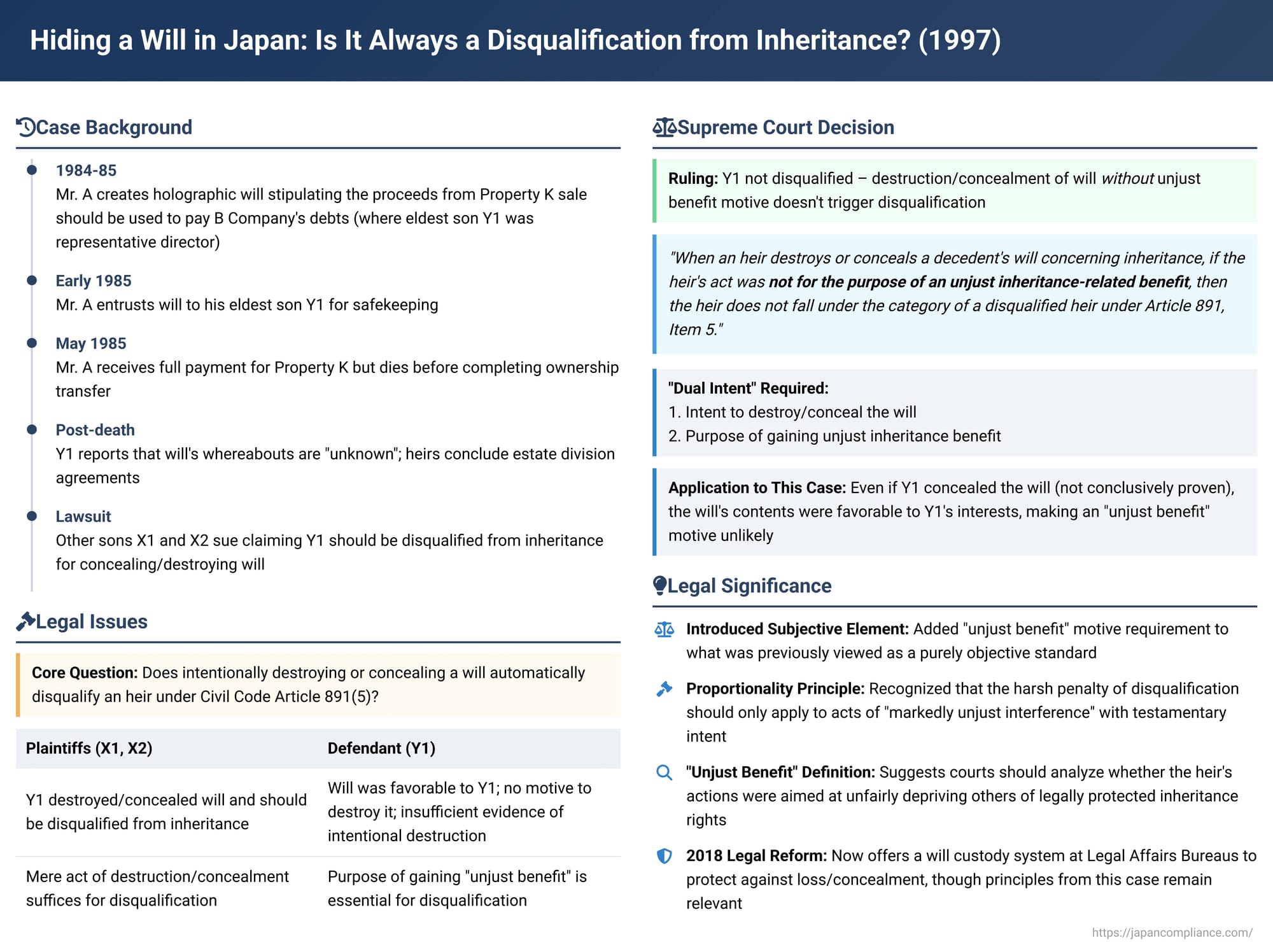

Hiding a Will in Japan: Is It Always a Disqualification from Inheritance? The Supreme Court Clarifies the "Unjust Benefit" Rule

Judgment Date: January 28, 1997 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

In a significant 1997 ruling, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a critical question in inheritance law: does an heir who destroys or conceals the deceased's will automatically lose their right to inherit? The Court's decision clarified that for an heir to be disqualified under Article 891, Item 5 of the Civil Code for such actions, it's not enough that they intentionally destroyed or hid the will; their actions must also have been motivated by the purpose of gaining an unjust inheritance-related benefit. This ruling introduced a crucial subjective element into the assessment of one of the gravest forms of misconduct an heir can commit concerning a testator's final wishes.

A Will Entrusted, Then Reportedly Lost: The Factual Background

The case involved the estate of Mr. A. Mr. A was in a chairman-like position at B Company, where his eldest son, Y1, served as the representative director. Mr. A had decided to sell a parcel of land he owned, known as "Property K" (which was then leased to Y2 Company), directly to Y2 Company. The primary intention behind this sale was to use the proceeds to pay off debts owed by B Company. By November 1984, a general agreement for this sale was reached between Mr. A and Y2 Company. By May 1985, a formal sales contract was executed, and the full purchase price was paid to Mr. A.

To make his intentions regarding this transaction unequivocally clear, around February or March 1985, Mr. A prepared a holographic will (a will written entirely in his own handwriting). This will essentially stated that the sale proceeds from Property K were to be considered a donation to B Company, and that his son Y1 was to use these funds to settle B Company's debts. The will also expressed Mr. A's wish that his other children consent to this arrangement. Mr. A entrusted this handwritten will to Y1 for safekeeping.

Mr. A passed away before the official ownership transfer registration for Property K to Y2 Company could be completed. His legal heirs included his eldest son Y1, his second son X1, his fourth son X2 (X1 and X2 being the plaintiffs in this case), and three other children, Y3 (a daughter), Y4 (a son), and Y5 (a daughter), who, along with Y1 and Y2 Company, were defendants in the lawsuit.

During the discussions among the heirs regarding the division of Mr. A's estate, Y1 reported that the holographic will entrusted to him by Mr. A could not be found; its whereabouts had become unknown. Consequently, he was unable to present it to the other heirs. Despite the will's absence, the heirs proceeded to conclude two estate division agreements:

- An agreement dated October 26, 1985, stated that to fulfill the pre-existing obligation to register the transfer of Property K to Y2 Company, Y1 would formally inherit Property K (presumably to then complete the sale).

- A further agreement dated June 17, 1986, stipulated that Y1 would inherit all other land and assets belonging to Mr. A. In consideration, Y1 was to pay 35 million yen each to his brothers X1 and X2, and 3 million yen to his sister Y3. The remaining children, Y4 and Y5, were to receive no inheritance under this particular agreement.

Dissatisfied with these arrangements and suspecting foul play concerning the will, X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit. Their primary claims were:

- A confirmation that Y1 had no right to inherit from Mr. A due to having been disqualified as an heir.

- A confirmation that the estate division agreements were invalid.

- The cancellation of various ownership transfer registrations made based on these agreements.

The grounds for Y1's alleged disqualification from inheritance included allegations that Y1 had either (1) forged Mr. A's will, (2) destroyed or concealed the will, or (3) fraudulently induced Mr. A to make the will. The appeal to the Supreme Court ultimately centered on the allegation of destruction or concealment of the will.

The Lower Courts' Rulings

- The first instance court dismissed the claims made by X1 and X2. It found that there was insufficient evidence to prove that Y1 had intentionally destroyed or concealed the will.

- The appellate court also dismissed the appeal from X1 and X2. However, it took a nuanced approach to the issue of will destruction or concealment. Without making a definitive factual finding on whether Y1 had actually destroyed or concealed the will, the appellate court stated that even if such an act had occurred, it would not automatically lead to Y1's disqualification under Civil Code Article 891, Item 5. The appellate court reasoned that for disqualification under this provision, the act of destruction or concealment must be committed "with the purpose of unjustly gaining or attempting to gain an inheritance-related benefit, or avoiding or attempting to avoid an inheritance-related disadvantage." In this specific case, the appellate court noted that the contents of the (now missing) will—directing sale proceeds to B Company, which Y1 managed and whose debts the sale was intended to clear—were largely favorable to Y1's interests or aligned with responsibilities he was expected to undertake. Therefore, the appellate court concluded that even if Y1 had destroyed or concealed it, he would not be a person falling under the disqualification criteria because the requisite "unjust benefit" motive was lacking.

X1 and X2 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that the appellate court had erred in its interpretation of Civil Code Article 891, Item 5.

The Supreme Court's Decision: "Unjust Benefit" Motive is Key for Disqualification

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, thereby upholding the appellate court's conclusion that Y1 was not disqualified from inheriting. The Supreme Court's core reasoning focused on the necessity of a specific subjective intent for disqualification under Article 891, Item 5:

The Court held that when an heir destroys or conceals a decedent's will concerning inheritance, if the heir's act was not for the purpose of an unjust inheritance-related benefit (相続に関して不当な利益を目的とするものでなかったとき, sōzoku ni kanshite futō na rieki o mokuteki to suru mono de nakatta toki), then the heir is not disqualified from inheriting under Civil Code Article 891, Item 5.

The Court elaborated that the underlying purpose of Article 891, Item 5 is to impose a civil sanction—the forfeiture of the qualification to be an heir—upon an heir who has committed a "markedly unjust interference" with a will (citing a previous Supreme Court decision from April 3, 1981). If the act of destroying or concealing a will was not aimed at securing an unjust inheritance-related benefit for the perpetrator, then such an act cannot be characterized as a "markedly unjust interference." Consequently, imposing the severe sanction of disqualification on someone who committed such an act (i.e., an act lacking the specific purpose of unjust benefit) would not align with the fundamental intent of Article 891, Item 5.

The Supreme Court found the appellate court's judgment, which was based on similar reasoning regarding the necessity of this unjust benefit purpose, to be correct and affirmed it.

Understanding Inheritance Disqualification (相続欠格, Sōzoku Kekkaku) in Japan

Article 891 of the Japanese Civil Code outlines specific grounds upon which a person automatically and by operation of law loses their right to inherit from a particular decedent. This is known as sōzoku kekkaku, or disqualification from inheritance. It is a serious consequence, effectively barring the individual from receiving any portion of the deceased's estate as an heir.

The grounds for disqualification listed in Article 891 include severe misconduct such as:

- Intentionally causing or attempting to cause the death of the decedent or any heir with a prior or equal claim to inheritance.

- Knowing that the decedent was killed by someone and failing to accuse or denounce the killer (with certain exceptions).

- Preventing the decedent from making, revoking, or altering a will by fraud or duress.

- Inducing the decedent to make, revoke, or alter a will by fraud or duress.

- Forging, altering, destroying, or concealing a decedent's will concerning inheritance.

This case specifically concerns the interpretation of Item 5.

The "Dual Intent" Requirement for Will Destruction/Concealment

A key legal debate surrounding Article 891, Item 5 has been whether the mere intentional commission of the prohibited act (e.g., deliberately tearing up a will, or knowingly hiding it) is sufficient for disqualification, or whether an additional, more specific subjective intent is also required. This second layer of intent is often referred to in legal discussions as a "dual intent" (二重の故意, nijū no koi) or "double intent." For Item 5, this typically translates to:

- The intent to commit the physical act of destruction or concealment.

- The further intent or purpose of thereby gaining an unjust inheritance-related benefit for oneself or causing an unjust detriment to other heirs.

This 1997 Supreme Court decision was the first by Japan's highest court to explicitly clarify that for disqualification due to the destruction or concealment of a will under Article 891, Item 5, this "dual intent"—specifically, the purpose of obtaining an unjust inheritance-related benefit—is indeed necessary. If this specific self-serving or unfairly detrimental motive is absent, the act of destruction or concealment, even if carried out knowingly, does not trigger the severe consequence of disqualification.

Why the "Unjust Benefit" Motive Matters

The Supreme Court's rationale for requiring this specific motive is rooted in the severity of the sanction of disqualification. Losing one's inheritance rights is a drastic outcome. The Court reasoned that such a penalty should be reserved for conduct that is not only intentional but also constitutes a "markedly unjust interference with a will."

- If an heir's actions, while technically amounting to destruction or concealment, were not aimed at unfairly skewing the inheritance distribution in their favor or wrongfully disadvantaging others, then those actions might not rise to the level of "markedly unjust interference" that the statute intends to penalize so severely.

- There could be scenarios where an heir might destroy or hide a will without an "unjust benefit" motive. For example, an heir who is bequeathed the entire estate in a will might, out of a desire to avoid family conflict or to achieve what they perceive as a fairer distribution, choose to conceal the will and agree to a division based on statutory inheritance shares. While the act of concealment is still improper, if it doesn't lead to an unjust outcome for others or an unfair gain for the concealer beyond what they might be entitled to, the motive for disqualification might be absent.

In the specific circumstances of Mr. Y1, the will in question directed the proceeds of a property sale towards B Company, an entity he managed and whose debts the sale was intended to clear. The will's contents were thus largely aligned with actions Y1 was expected to take or that benefited an entity tied to his responsibilities. This context made it less probable that any alleged destruction or concealment of such a will by Y1 was driven by a motive to secure a personal, unjust inheritance-related benefit at the expense of the overall testamentary plan or the fundamental rights of other heirs.

Defining "Unjust Inheritance-Related Benefit"

The Supreme Court's ruling did not provide an exhaustive, universally applicable definition of what constitutes an "unjust inheritance-related benefit." However, legal commentary and subsequent jurisprudence suggest that a key factor is whether the heir's actions were intended to unfairly deprive other heirs of their legal entitlements, particularly their "legally reserved portion" (iryūbun, 遺留分). The iryūbun is a concept in Japanese inheritance law similar to a forced or indefeasible share, which guarantees certain close relatives (like children and spouses) a minimum portion of the deceased's estate, even if a will attempts to disinherit them or leave them less.

- If an heir destroys or conceals a will with the aim of preventing other heirs from claiming their legally reserved portions, this would very likely be considered acting for an unjust benefit.

- Conversely, if an heir conceals a will that is highly favorable to them but then agrees to an estate division that fully respects or even exceeds the legally reserved portions of other heirs, the "unjust benefit" motive might be deemed absent.

The interplay between honoring a testator's expressed wishes (even if they might reduce some heirs' shares) and protecting the statutory rights of heirs (like the iryūbun) can make the assessment of "unjust benefit" complex. This Supreme Court ruling indicates that the heir's purpose in relation to the inheritance distribution is the critical element.

Recent Legal Reforms to Protect Wills (2018)

Recognizing the inherent vulnerabilities associated with traditional holographic wills (which, until recent reforms, had to be entirely handwritten, dated, and signed by the testator), Japan introduced significant legal reforms in 2018:

- Relaxation of Holographic Will Formalities: While the main text of a holographic will must still be handwritten, an attached inventory of assets can now be typewritten, printed, or created by other means, though each page of such an inventory must be signed and sealed by the testator (Civil Code Art. 968(2)).

- Official Custody System for Holographic Wills: A new system was established (Act on Custody of Holographic Wills by Legal Affairs Bureaus, Law No. 73 of Heisei 30 (2018)) allowing testators to deposit their original holographic wills with Legal Affairs Bureaus for official safekeeping. This system aims to significantly reduce the risks of wills being lost, concealed, forged, or altered after the testator's death, as the Legal Affairs Bureau maintains the original and provides certified copies after probate.

Despite these valuable reforms, testators still have the option to create and keep holographic wills privately without utilizing the official custody system. Therefore, the legal principles governing disqualification for destroying or concealing such wills, as clarified by the 1997 Supreme Court decision, remain highly relevant for situations where the official custody system is not used and a will's integrity is subsequently compromised by an heir's actions.

Conclusion: Motive is a Decisive Factor in Will Tampering Cases Leading to Disqualification

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1997 decision in this case provides a critical interpretation of the law on inheritance disqualification. It establishes that merely destroying or concealing a will, even if done intentionally, is not sufficient to disqualify an heir under Article 891, Item 5 of the Civil Code. The act must be accompanied by the motive or purpose of gaining an unjust inheritance-related advantage. This ruling tempers a strict, purely objective application of a severe penalty, requiring courts to delve into the heir's subjective purpose when assessing such misconduct. It underscores a judicial approach that seeks to reserve the harsh sanction of disqualification for situations involving genuinely egregious and self-serving interference with the testamentary process, rather than penalizing acts that, while improper, may lack the specific intent to unfairly manipulate inheritance outcomes.