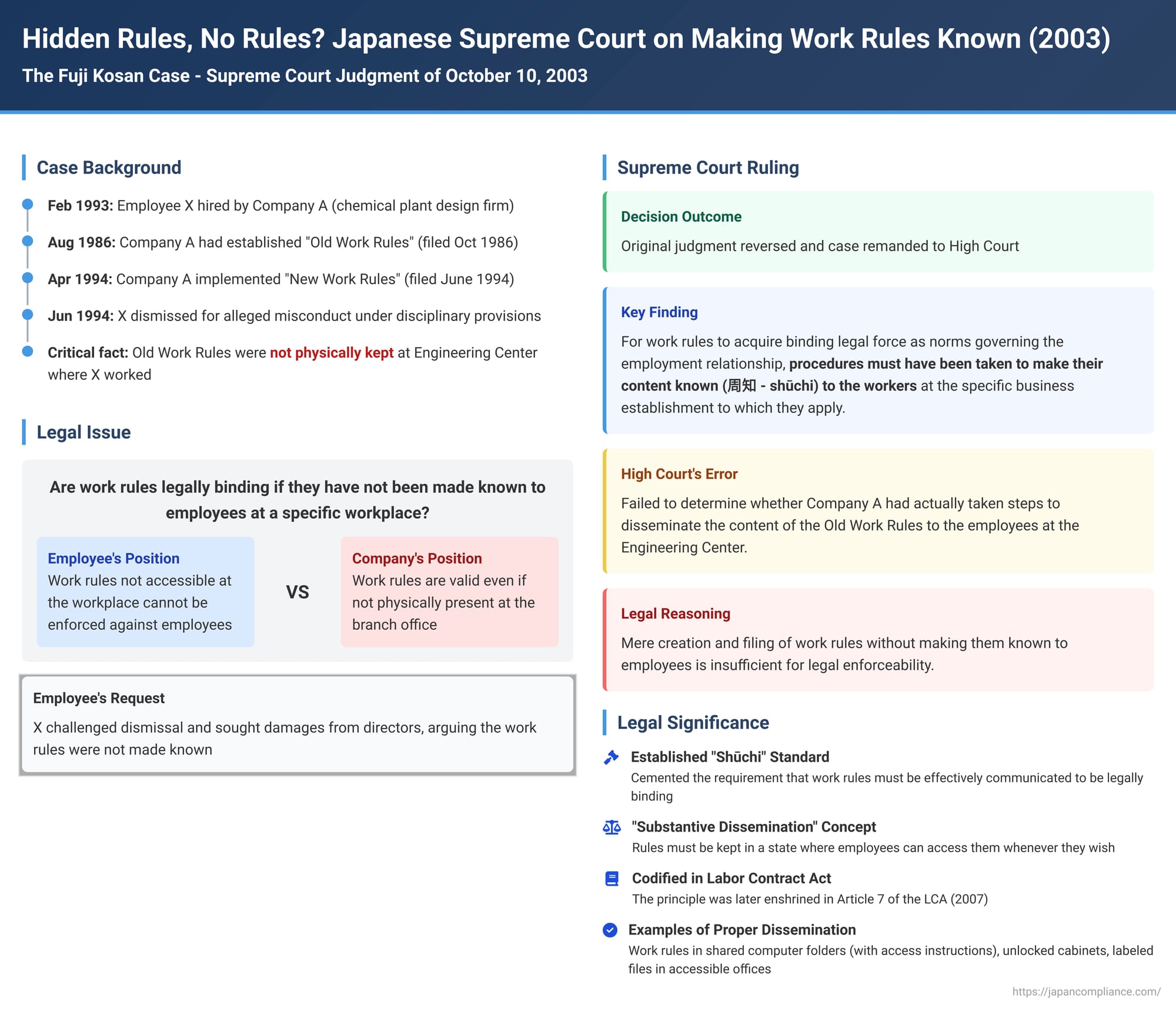

Hidden Rules, No Rules? Japanese Supreme Court on Making Work Rules Known

In the Japanese employment landscape, work rules (就業規則 - shūgyō kisoku) are fundamental documents. Typically drafted by the employer, they outline the terms and conditions of employment, covering everything from working hours and wages to disciplinary procedures. The Labor Standards Act imposes several obligations on employers with ten or more employees, including the creation of these rules, consultation with an employee representative, filing with the Labor Standards Inspection Office, and, crucially, making them known to employees (周知 - shūchi). The significance of this last step – dissemination – and its impact on the enforceability of work rules was brought into sharp relief by the Supreme Court of Japan in the Fuji Kosan case, a judgment delivered on October 10, 2003. This case clarified that merely creating and filing work rules is not enough; they must be effectively communicated to employees to have binding legal force.

The Fuji Kosan Dispute: A Dismissal Challenged on Procedural Grounds

The case involved Mr. X, an employee of Company A, a firm specializing in the design and construction of chemical plants. X was employed in February 1993 and worked at Company A's "Engineering Center" (hereinafter "the Center"), a design contracting division located in C City, while the company headquarters was in B City.

Company A had established a set of "Old Work Rules" on August 1, 1986, with the consent of an employee representative, and filed these with the D Labor Standards Inspection Office (LSIO) on October 30, 1986. Subsequently, Company A decided to implement "New Work Rules," which amended the old ones, effective April 1, 1994. Consent from the employee representative for these New Work Rules was obtained on June 2, 1994, and they were filed with the D LSIO on June 8, 1994. Both the Old and New Work Rules contained provisions detailing grounds for disciplinary dismissal.

Between September 1993 and May 30, 1994, X was alleged to have engaged in misconduct, including failing to adequately respond to client requests, causing various troubles, and exhibiting insubordination towards superiors. On June 15, 1994, Company A invoked the disciplinary dismissal provisions of the New Work Rules and dismissed X.

A critical fact emerged: prior to his dismissal, X had inquired with Y3, a director of Company A and the head of the Center at the time, about the work rules applicable to employees at the Center. During this inquiry, it was revealed that the Old Work Rules were not physically kept or made available at the Center.

X initiated legal proceedings, which included a claim (乙事件 - Otsu case) against directors of Company A (Y1, Y2, Y3, and one other) for damages, alleging their involvement in an illegal disciplinary dismissal. The Osaka District Court initially ruled that the dismissal was valid and dismissed X's claim against the directors. The Osaka High Court upheld this, reasoning that even if the Old Work Rules were not physically present at the Center, they were still effective for employees working there. The High Court also viewed the disciplinary grounds in the New Work Rules as merely a more detailed articulation of those in the Old Work Rules, thus validating the dismissal. X appealed the part of the judgment concerning the directors' liability to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark 2003 Decision

The Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further deliberation. The Supreme Court's reasoning focused on the fundamental requirements for work rules to be enforceable.

Reiteration of Established Principles:

The Court began by referencing two established principles from its prior jurisprudence:

- For an employer to take disciplinary action against an employee, the types of disciplinary measures and the grounds for such actions must be stipulated in advance in the work rules (a principle from the Kokutetsu Sapporo Driving District case).

- Work rules possess the nature of legal norms (a principle from the Shuhoku Bus case).

The Core Finding: Dissemination (Shūchi) as a Prerequisite for Binding Force:

Building on these principles, the Supreme Court delivered its crucial finding: For work rules to acquire binding legal force as norms governing the employment relationship, procedures must have been taken to make their content known (周知 - shūchi) to the workers at the specific business establishment to which they apply.

The Lower Court's Error:

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred significantly. The High Court had confirmed that Company A obtained employee representative consent for the Old Work Rules and filed them with the LSIO. However, it had failed to make a finding as to whether Company A had actually taken steps to disseminate the content of these Old Work Rules to the employees working at the Center. Despite this omission, the High Court affirmed the legal normative effect of the Old Work Rules and, consequently, the validity of X's dismissal. The Supreme Court ruled that this constituted an error in the application of law resulting from insufficient deliberation of the facts. The case was sent back to the High Court to properly investigate whether the Old Work Rules had indeed been made known to the Center's employees.

Understanding "Shūchi": The Standard for Making Rules Known

The Fuji Kosan judgment itself did not provide an exhaustive definition of what constitutes adequate "shūchi". However, subsequent administrative guidance and case law have fleshed out this concept, leading to the idea of "substantive dissemination" (実質的周知 - jisshitsuteki shūchi).

This standard means that the work rules must be kept in a state where employees can know their existence and content whenever they wish to do so. It is not strictly limited to the specific methods of dissemination listed in Article 106, Paragraph 1 of the Labor Standards Act (such as posting in a conspicuous location, providing a copy to each worker, or making them readily available for inspection). Rather, the focus is on whether, in substance, the rules were placed in a condition where the group of workers at a particular establishment could access and understand their content.

Examples from court cases illustrate this "substantive dissemination" standard:

- Shūchi Affirmed:

- Work rules, along with wage tables, were stored in a shared folder on the company's internal LAN, accessible to employees.

- Work rules were kept in an unlocked cabinet in an administrative office that employees regularly entered.

- Work rules were contained in a clearly labeled file ("Work Rules") placed on a desk or shelf in an operations office that crew members frequented.

- A copy of the work rules was permanently kept in a labeled box ("Work Rules") on a desk in an accounting office that employees could freely enter.

- Shūchi Negated:

- Merely allowing an employee to view the work rules on a single occasion was deemed insufficient.

- Saving the work rules as an electronic file on a shared company computer folder was not considered "shūchi" when employees (particularly foreign employees in the cited case) were not informed of the file's location or how to access it.

- Adopting the work rules of another company (even a parent or core group company) and placing them on a shelf in an employee break room was insufficient if employees could not recognize these rules as their own company's applicable rules and understand their content as such.

Therefore, "substantive dissemination" effectively requires that the rules are clearly identifiable as the applicable work rules for that specific workplace, that employees are informed of how and where to access them, and that they are genuinely able to consult the rules if they choose to.

The requirements for "shūchi" can be even more stringent when it comes to changes in work rules, especially those that are disadvantageous. While one case (Aozora Bank) found "substantive shūchi" for a revised salary system even when full details were available only upon inquiry (due to concerns about external leaks), other pre-LCA cases indicated that failing to explain the specific content, merits, and demerits of changes (e.g., in wage amounts) would not constitute adequate dissemination, even if some general information or viewing opportunity was provided. Changes necessitate clarity, specificity, and often, a more formal approach to ensure employees understand the alterations. For instance, merely outlining changes in a company newsletter, without clearly stating that this constitutes an amendment to the official work rules and without the formal structure of work rules, may not be sufficient for the change to take legal effect.

The Broader Context: Work Rules and the Labor Contract Act

The principle articulated in the Fuji Kosan case – that dissemination is essential for the binding force of work rules – was later enshrined in Article 7 of the Labor Contract Act (LCA), enacted in 2007. This article stipulates that if an employer has disseminated reasonable work rules to its employees, the working conditions shall be as provided by those work rules (unless there's a separate agreement for more favorable terms). Thus, "shūchi" became a statutory requirement alongside the "reasonableness" of the rules' content for them to govern employment contracts.

Dissemination is now understood as a key prerequisite not only for the general normative effect of work rules (LCA Article 7) but also for the binding effect of adverse changes made to them (LCA Article 10). The Fuji Kosan ruling can be seen as reconciling or clarifying earlier jurisprudence, like the 1952 Asahi Shimbun Ogura Branch case. The earlier case suggested that a lack of subsequent dissemination methods prescribed by the LSA did not inherently negate the work rules' validity. The commentary on Fuji Kosan suggests the Asahi Shimbun case likely meant that dissemination methods other than those specifically listed in the LSA could still be valid, rather than implying that no form of dissemination was needed at all for the rules to have normative effect.

Implications for Employers and Employees

The Fuji Kosan decision carries significant practical implications:

- For Employers: It is paramount not only to create, consult upon, and file work rules but also to actively and effectively ensure they are accessible and known to all employees at every relevant workplace. This includes branch offices or remote centers. Methods should be chosen that guarantee employees can readily access and understand the rules. This is not a mere administrative formality but a critical condition for the rules' enforceability, especially concerning disciplinary actions.

- For Employees: The ruling reinforces their right to be clearly informed of the regulations governing their employment conditions, conduct, and particularly, the grounds and procedures for disciplinary measures. An employer cannot typically enforce rules that it has not made known.

A Note on Director Liability

It is important to remember that the specific appeal in the Fuji Kosan case before the Supreme Court concerned the potential liability of Company A's directors for their involvement in X's dismissal. The Supreme Court's decision to remand the case meant that the validity of the dismissal itself (and by extension, the directors' related liability) needed to be re-examined in light of the "shūchi" requirement. However, legal commentary points out that even if a disciplinary dismissal is ultimately found to be invalid (for instance, due to a lack of proper dissemination of the underlying work rules), this does not automatically establish personal tort liability for the directors who made the decision. Proving director liability would typically require further evidence of negligence or intentional wrongdoing on their part in the decision-making process.

Conclusion

The Fuji Kosan Supreme Court case of 2003 was a landmark decision that cemented the requirement of "shūchi" (dissemination) as an indispensable element for work rules to be legally binding on employees in Japan. By emphasizing that employees must be able to know and access the rules that govern their employment, the Court underscored the importance of transparency and procedural fairness. This ruling, and its subsequent incorporation into the Labor Contract Act, continues to guide employers in their obligations and empower employees by ensuring they are aware of their workplace rights and responsibilities. It serves as a critical reminder that for workplace rules to be effective and enforceable, they must first be effectively communicated.