Heirs of Heirs: Japanese Supreme Court on Life Insurance Beneficiary Succession When the Beneficiary Dies First

Date of Judgment: September 7, 1993

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 1100 (o) of 1990 (Insurance Claim Case)

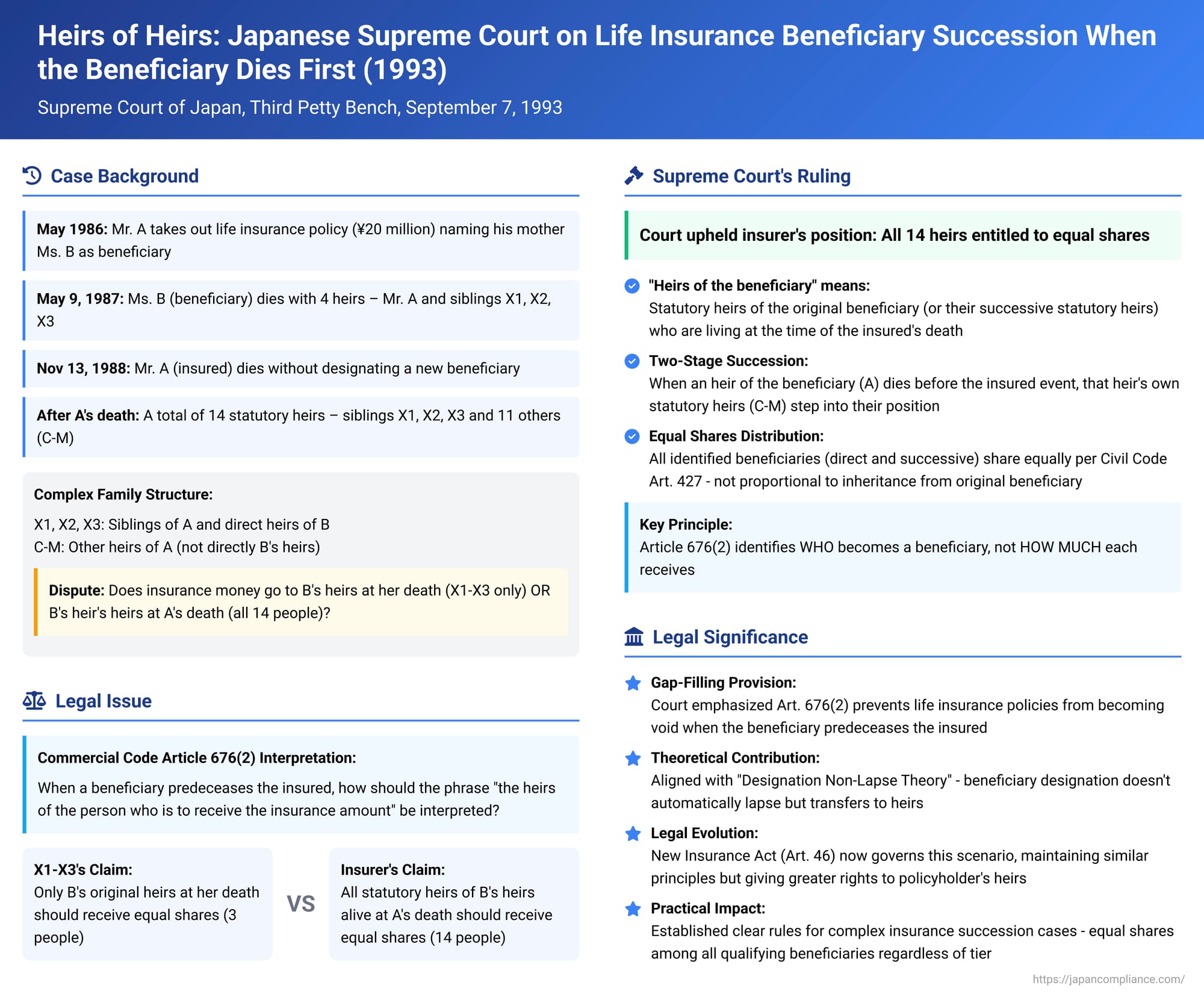

Life insurance policies are designed to provide financial security upon the occurrence of an insured event, typically the death of the insured. A critical element is the designation of a beneficiary. But what happens when the named beneficiary dies before the insured, and the insured subsequently passes away without appointing a new beneficiary? Who is then entitled to the insurance proceeds? This complex scenario, fraught with potential ambiguities, was the subject of a significant ruling by the Japanese Supreme Court on September 7, 1993. The case delved into the interpretation of the then-applicable Commercial Code to determine the rightful recipients of life insurance funds in such circumstances.

The Unfolding Tragedy: Facts of the Case

In May 1986, Mr. A entered into a life insurance contract with Y Insurance Company[cite: 1]. The policy insured Mr. A's life for a sum of 20 million yen, and he designated his mother, Ms. B, as the beneficiary[cite: 1].

Tragedy struck when Ms. B, the designated beneficiary, passed away on May 9, 1987[cite: 1]. Subsequently, on November 13, 1988, Mr. A, the insured, also died[cite: 1]. Critically, Mr. A had not designated a new beneficiary for the life insurance policy after his mother's death[cite: 1].

The family structure added layers of complexity to the ensuing legal dispute. At the time of Ms. B's death, her statutory heirs were her son, Mr. A (the insured himself), and Mr. A's three siblings, X1, X2, and X3 (the plaintiffs/appellants in the Supreme Court case, who were also Ms. B's children)[cite: 1]. Thus, Ms. B had a total of four statutory heirs when she died[cite: 1].

When Mr. A later died, his own statutory heirs were numerous. They included his siblings X1, X2, and X3, as well as a group designated C through M, who were Mr. A's half-siblings and their children, totaling fourteen statutory heirs for Mr. A[cite: 1].

X1, X2, and X3 initiated a claim against Y Insurance Company, asserting that under the provisions of the old Commercial Code (specifically, Article 676, paragraph 2, prior to the enactment of the new Insurance Act), the statutory heirs of Ms. B at the time of Ms. B's death became the rightful beneficiaries[cite: 1]. Based on this, they each claimed a share of the 20 million yen insurance payout, arguing for a sum of 6,666,666 yen each[cite: 1].

Y Insurance Company contested this interpretation[cite: 1]. The insurer argued that the same legal provision meant that if a statutory heir of the original designated beneficiary (like Mr. A, who was an heir of Ms. B) also died before the insurance payout, then that deceased heir's own statutory heirs (i.e., successive heirs) would step in[cite: 1]. Therefore, Y Insurance Company contended that all fourteen of Mr. A's statutory heirs (X1-X3 plus C-M) were equally entitled to the insurance proceeds[cite: 1]. Both the first instance court and the appellate court agreed with Y Insurance Company's position, leading X1, X2, and X3 to appeal to the Supreme Court[cite: 1].

The Legal Framework: Old Commercial Code Article 676(2)

The dispute hinged on the interpretation of Article 676, paragraph 2, of the Commercial Code then in force. This provision addressed the situation where the designated beneficiary of a life insurance policy dies before the insurance proceeds become payable. It provided a mechanism for determining who would receive the insurance money to prevent the policy from failing due to a lack of a living beneficiary. The core phrase under scrutiny was "the heirs of the person who is to receive the insurance amount."

The Supreme Court's Interpretation and Ruling

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1, X2, and X3, upholding the lower courts' decisions[cite: 1]. The Court provided a detailed interpretation of the Commercial Code provision:

- Defining "The Beneficiary's Heirs": The Court clarified that the phrase "heirs of the person who is to receive the insurance amount" in Article 676(2) refers to the statutory heirs of the originally designated beneficiary (in this case, Ms. B), or their successive statutory heirs, who are actually living at the time of the insured's (Mr. A's) death[cite: 1]. The Court noted that this interpretation was consistent with a long-standing precedent from the Daishin-in (the Great Court of Cassation, the predecessor to the Supreme Court).

- Purpose of the Provision: The fundamental purpose of Article 676(2) was to supplement the beneficiary designation made by the policyholder[cite: 1]. It aimed to prevent, as far as possible, a scenario where no beneficiary existed to claim the proceeds[cite: 1]. The Court explained that if the designated beneficiary died, and subsequently the policyholder (who in this case was also the insured) died without an opportunity to make a new designation as permitted under Article 676(1), then the statutory heirs of the initial designated beneficiary (or their successive statutory heirs) who were alive at the moment the insured died would be confirmed as the beneficiaries[cite: 1].

- When an Heir is Also the Insured: The Court explicitly stated that this principle holds true even if one of the statutory heirs of the designated beneficiary happens to be the policyholder/insured themselves[cite: 1]. In this case, Mr. A was an heir to Ms. B. When Mr. A subsequently died, his own statutory heirs (C through M, along with X1-X3 who were heirs of both A and B) effectively stepped into Mr. A's position as successive heirs of the original beneficiary, Ms. B, for the purpose of the insurance policy[cite: 1].

- Division of Shares Among Multiple Beneficiaries: Crucially, the Supreme Court addressed how the insurance proceeds should be divided if the application of Article 676(2) resulted in multiple individuals qualifying as beneficiaries (some being direct heirs of the original beneficiary, others being successive heirs). The Court ruled that the respective shares of these ultimate beneficiaries are to be equal[cite: 1]. This determination was based on the application of Article 427 of the Civil Code, which governs divisible claims among multiple creditors, stipulating equal shares in the absence of other provisions[cite: 1].

- Nature of Article 676(2): The Court emphasized that Article 676(2) of the Commercial Code does not provide for the inheritance or succession of the designated beneficiary's status or position itself[cite: 1]. Nor does it lay down rules for determining the specific proportions of the insurance claim if multiple beneficiaries are identified through its application[cite: 1]. Instead, its function is to identify who becomes a beneficiary by focusing on their status as a statutory heir (or successive statutory heir) of the originally designated person[cite: 1]. Once these individuals are identified as beneficiaries who acquire the insurance claim right "originally" upon the occurrence of the insured event, the proportion of their claims is determined by general civil law principles – namely, Civil Code Article 427, leading to equal shares[cite: 1].

Outcome of the Case:

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that Mr. A was one of Ms. B's four statutory heirs. Upon Mr. A's death, his own statutory heirs (the eleven individuals C-M, plus X1-X3 who were already direct heirs of B) took Mr. A's place in the chain of succession from Ms. B for the purpose of the insurance payout. Therefore, the ultimate beneficiaries were the three appellants (X1, X2, X3, as direct heirs of B) and the eleven other heirs of A (as successive heirs of B via A), totaling fourteen individuals[cite: 1]. Each of these fourteen beneficiaries was entitled to an equal 1/14th share of the 20 million yen death benefit[cite: 1]. The High Court's judgment was affirmed as correct[cite: 1].

Delving Deeper: Theories and Implications

The Supreme Court's 1993 decision provided a clear, albeit complex, resolution under the old Commercial Code. Legal commentary offers further context on the theoretical underpinnings and subsequent developments.

The Role of Article 676(2) – A Statutory Gap-Filler:

The provision served as a crucial statutory mechanism to prevent life insurance policies from becoming unpayable due to the absence of a living, designated beneficiary[cite: 1]. It was essentially a default rule that kicked in when the policyholder hadn't made alternative arrangements.

Competing Interpretive Theories Under the Old Law:

The scenario of a beneficiary predeceasing the insured had long been a subject of academic debate, leading to two main interpretive theories[cite: 3]:

- Designation Lapse Theory (shitei shikkō setsu): This view held that when the originally designated beneficiary died, the designation itself lapsed or became ineffective[cite: 3]. Consequently, the life insurance contract would effectively transform into a contract for the policyholder's own benefit[cite: 3]. Article 676(2) was then seen as a somewhat "acrobatic" policy-driven intervention to channel the proceeds not to the policyholder's estate (as one might expect if it became a policy for their own benefit), but rather to the heirs of the original designated beneficiary who were alive at the time of the policyholder's/insured's death, provided no redesignation had occurred[cite: 3]. Critics pointed to the apparent logical inconsistency: if the policy had truly become one for the policyholder's own benefit, then the policyholder's heirs should logically receive the proceeds, not the original (lapsed) beneficiary's heirs[cite: 3].

- Designation Non-Lapse Theory (shitei hi-shikkō setsu): This alternative theory argued that a life insurance contract made for the benefit of a third party does not automatically convert into a contract for the policyholder's own benefit unless the policyholder clearly expresses such an intention[cite: 3]. Instead, the law effectively presumes or "fictions" the continuous existence of a beneficiary[cite: 3]. Under this view, when the designated beneficiary dies, their statutory heirs immediately step into a "provisional beneficiary" status[cite: 3]. If one of these provisional heirs also dies before the insured event, their own heirs would then acquire that provisional status (this is sometimes referred to as a "two-stage application" or iterative application of Article 676(2))[cite: 3]. Throughout this period, the policyholder retained the right to formally change the beneficiary, which would extinguish any such provisional status[cite: 3]. The Supreme Court's 1993 ruling, particularly its determination that the ultimate beneficiaries share equally regardless of their tier in the succession from the original beneficiary, can be seen as consistent with certain formulations of this non-lapse theory[cite: 3].

The Shift with the New Insurance Act:

It is crucial to note that the legal landscape concerning this issue has evolved since the 1993 decision. The new Insurance Act of Japan, which came into force after this case was decided, now contains Article 46, which directly addresses the scenario of a beneficiary predeceasing the insured[cite: 1]. Some commentators suggest Article 46 aligns more with the designation non-lapse theory, as it states that upon the death of the designated beneficiary, "all of their heirs become beneficiaries"[cite: 3].

A more fundamental change introduced by the new Insurance Act is the enhanced right of the policyholder's heirs. Under the old Commercial Code (Article 675(2)), if the policyholder died, the beneficiary designation was considered "fixed," and the policyholder's heirs generally could not change it[cite: 1]. The new Insurance Act, however, generally allows the policyholder's heirs to change the beneficiary if the policyholder dies before the insured event occurs (unless the original policyholder had expressed an intent that the designation could not be changed)[cite: 1, 3].

This new power for the policyholder's heirs has profound implications for the theoretical basis of rules governing beneficiary predecease[cite: 3]. Consider the sequence: (1) original beneficiary dies -> (2) original policyholder dies -> (3) insured event (insured's death). Between stages (2) and (3), the policyholder's heirs now have the ability to step in and change the beneficiary based on their own intentions and their own "value relationship" with a newly chosen beneficiary[cite: 3]. This significantly weakens the rationale for automatically channeling the insurance proceeds to the heirs (and potentially remote successive heirs) of the original designated beneficiary[cite: 3, 4]. The presumed intent of the original policyholder, which underpinned much of the old law's interpretation, becomes less compelling when their own heirs can actively reshape the policy's beneficiary provisions[cite: 4]. The new policyholder's heirs may have no connection to, or intent to benefit, the original deceased beneficiary's heirs[cite: 4].

The 1993 Judgment's Enduring Logic (Within Its Historical Context):

Within the framework of the old Commercial Code, the 1993 Supreme Court decision sought to ensure that the insurance proceeds found their way to identifiable living persons rather than lapsing into an unclaimable state[cite: 1]. It provided a clear, if intricate, rule for identifying these individuals and, importantly, established a straightforward principle of equal shares among them, avoiding potentially more complicated calculations based on inheritance ratios from the original beneficiary[cite: 1].

Significance of the 1993 Ruling

The Supreme Court's September 7, 1993, judgment was highly significant for its time:

- It provided an authoritative clarification of the term "beneficiary's heirs" under the old Commercial Code Article 676(2), confirming it meant those alive at the insured's death, potentially including successive heirs[cite: 1].

- It established the key principle that when multiple individuals become statutory beneficiaries through this mechanism, they share the proceeds equally[cite: 1].

- The decision offered a (then) definitive resolution to a recurring and complex problem in life insurance law, undoubtedly influencing subsequent legislative considerations that led to the new Insurance Act[cite: 1].

Concluding Thoughts

The 1993 Supreme Court decision meticulously navigated the complexities of beneficiary succession under the old Commercial Code, striving for a practical outcome that ensured policy proceeds were distributed. While the specific statutory provision it interpreted has since been replaced by the new Insurance Act, the case remains an important illustration of the legal challenges arising from the interplay of insurance law and succession principles. The evolution of the law, particularly the introduction of the policyholder's heirs' right to change beneficiaries, continues to fuel discussion about the most theoretically sound and equitable way to determine entitlement when a designated beneficiary predeceases the insured[cite: 1, 3, 4]. This ruling stands as a testament to the judiciary's role in interpreting and applying statutory rules to often tragic and unforeseen family circumstances.