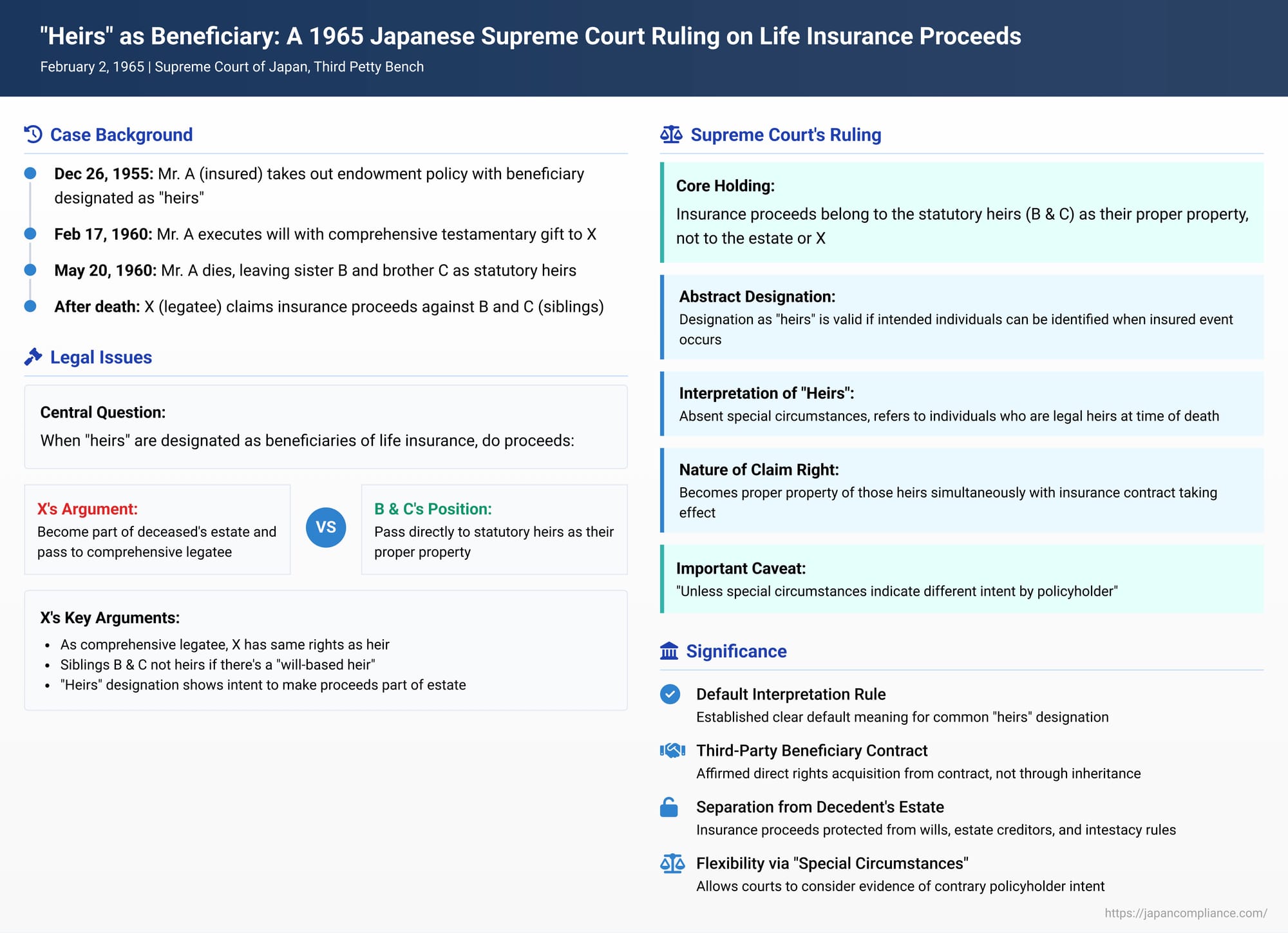

"Heirs" as Beneficiary: A 1965 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Life Insurance Proceeds and Estate Assets

Date of Judgment: February 2, 1965

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 1028 (o) of 1961 (Insurance Claim Case)

When drafting or interpreting life insurance policies, the designation of a beneficiary is of paramount importance. While often a specific individual is named, sometimes more general terms are used, such as "heirs." This seemingly simple designation can lead to complex legal questions: Do the insurance proceeds become part of the deceased insured's general estate, to be distributed according to a will or intestacy laws? Or do they pass directly to the individuals who qualify as "heirs" at the time of death, as their own separate property, independent of the estate? A pivotal 1965 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan addressed this very issue, offering significant clarification.

The Factual Background

The case centered on Mr. A, who, on December 26, 1955, entered into an endowment insurance contract with Y Insurance Company. Under this policy, Mr. A himself was the insured. The policy stipulated that if the insurance period matured during A's lifetime, A would be the beneficiary. However, if A were to die during the policy term, the death benefit beneficiary was designated simply as "heirs" (相続人 - sōzokunin).

Mr. A's family situation was somewhat unique: he had no spouse, no children or other lineal descendants, and no parents or other lineal ascendants. His closest living relatives were an older sister, B, and a younger brother, C.

A significant event occurred on February 17, 1960, when Mr. A executed a notarized will. In this will, A bequeathed his entire estate to an individual, X, through what is known in Japanese law as a "comprehensive testamentary gift" (包括遺贈 - hōkatsu izō). This type of gift typically entitles the recipient to a status similar to that of an heir concerning the rights and obligations related to the bequeathed property.

Mr. A passed away on May 20, 1960.

Following A's death, X, the comprehensive legatee, laid claim to the insurance proceeds from Y Insurance Company. X's argument was twofold:

- As a comprehensive legatee, X argued that under Article 990 of the Japanese Civil Code, they possessed the same rights and obligations as an heir and, therefore, acquired the right to the insurance money upon A's death.

- X further contended that siblings (like B and C) only become statutory heirs in the absence of heirs with prior ranking (such as a spouse or children). X asserted that since there was, in effect, an "heir by will" (X, due to the comprehensive gift), B and C were not A's heirs from the outset. Therefore, X claimed to be the "heir" specified in the insurance policy's beneficiary clause.

During the appellate stage, X also argued that when an insurance policy designates the beneficiary merely as "heirs" without naming specific individuals, this should be interpreted as the policyholder's intention to make the insurance claim right a part of the deceased's heritable estate, subject to the general rules of inheritance.

Lower Court Decisions:

The court of first instance dismissed X's claim. It held that a comprehensive legatee is not, strictly speaking, an "heir" in the statutory sense. More importantly, it found that designating "heirs" as beneficiaries in an insurance policy means specifying the individuals who are heirs, and the insurance claim right thus belongs to them as their proper property (固有財産 - koyū zaisan), separate from the deceased's estate.

The Tokyo High Court, acting as the appellate court, also dismissed X's appeal. It reasoned that:

- Japanese law at the time recognized only statutory inheritance; the concept of designating heirs by will was not permitted.

- Even if a comprehensive testamentary gift effectively left no portion of the estate for the siblings (B and C), this did not strip them of their underlying status as potential statutory heirs.

- Crucially, when "heirs" are designated as beneficiaries, their right to the insurance proceeds arises directly from the insurance contract itself, not through the process of succeeding to the deceased's assets via inheritance. Consequently, the claim right belonged to A's statutory heirs, B and C, as their proper property.

X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment and Rationale

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated February 2, 1965, dismissed X's appeal. The Court affirmed that the insurance proceeds belonged to A's statutory heirs (B and C) as their proper property and did not form part of A's estate to be distributed under the comprehensive testamentary gift to X.

The Court's reasoning can be summarized as follows:

- Validity of Abstract Designation: Even if an insurance contract abstractly designates the beneficiary in the event of the insured's death as "heirs," without listing specific names, such a designation is valid, provided that the intended persons can be identified at the time the insured event (death) occurs by reasonably inferring the policyholder's intent.

- Interpretation of "Heirs": In the absence of "special circumstances" (tokudan no jijō - 特段の事情), such a designation ("heirs") should be interpreted as a contract for the benefit of others (a third-party beneficiary contract). Specifically, it designates as beneficiaries those individuals who are to be the legal heirs of the insured at the time of the insured's death—that is, at the moment the insurance claim right arises. The Court explicitly stated that a prior Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation, the predecessor to the Supreme Court) precedent reflecting this view did not need to be revised.

- Nature of the Claim Right—Proper Property: When individuals who are to be the heirs at the time the claim right arises are thus specifically designated, the right to claim the insurance proceeds becomes the proper property of those heirs simultaneously with the insurance contract taking effect. This right is considered to be separate and distinct from the estate of the insured (who, in this case, was also the policyholder).

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court found the appellate court's judgment—that the insurance claim right belonged to the heirs' proper property and not to the deceased's heritable estate—to be just and affirmed it.

Elaborating on the Court's Interpretation

The Supreme Court's 1965 ruling provides a default rule for a common but potentially ambiguous beneficiary designation. The commentary and legal scholarship surrounding this decision offer further insights into the nuances.

1. Abstract Designations and Identifying the Beneficiary:

The Court confirmed that an abstract designation like "heirs" is valid as long as the individuals can be ascertained when the insurance event occurs. This pragmatic approach avoids invalidating designations simply because names aren't explicitly listed. The core interpretative task is to determine the policyholder's intent. If the expressed intent is ambiguous, the law seeks to establish the policyholder's "rational intent".

2. "Heirs": Part of the Estate or Proper Property of Individuals?

This was the central ambiguity. Two main schools of thought existed:

- One view, a minority one, suggested that designating "heirs" was merely an advisory note indicating that the proceeds would be inherited through the estate, effectively making them part of the deceased's heritable property.

- The prevailing view, which the Supreme Court adopted, is that such a designation identifies the individuals who are legal heirs at a specific point in time (usually, at the insured's death) to receive the proceeds directly as their own right, not through the mechanics of inheritance from the estate.

While the judgment mentions reasonably inferring the policyholder's intent, it doesn't explicitly detail the basis for this inference. Legal scholars offer various justifications:

- Some argue that the socio-economic purpose of life insurance, often intended to protect the insured's dependents, supports interpreting such designations as contracts for the benefit of others, thus channeling funds directly to them. However, this rationale alone might be insufficient, as whether proceeds are deemed proper property or estate property does not unilaterally determine all legal consequences, such as their availability to the deceased's creditors in certain situations.

- A more compelling line of reasoning, aligning with the idea of rational intent, is that if a policyholder simply wanted the insurance proceeds to become part of their general estate, they could achieve this by not designating any specific beneficiary for the death benefit. The act of writing "heirs" in the beneficiary field implies a positive intent to have those individuals who qualify as heirs receive the funds directly. This interpretation gives meaning to the policyholder's active designation.

The Court did, however, include the important caveat "unless there are special circumstances". This allows for deviations from the default interpretation if specific facts clearly indicate a different intent by the policyholder—for instance, if the insured had expressed to the insurer an intention to use the death benefit to settle their debts.

3. Timing: Which Heirs Are Designated?

The judgment clarifies that the "heirs" are those who hold that status at the time of the insured event—the insured's death. This is logical because the composition of one's legal heirs can change between the time a policy is taken out and the time of death due to births, deaths, marriages, or divorces. Designating "heirs at the time of death" obviates the need for the policyholder to constantly update the beneficiary designation with every change in family structure.

4. Consideration of Specific Individual Circumstances:

Some legal commentators have questioned whether the Court should have considered more of A's individual circumstances—such as his age, family relationships, his level of legal understanding, the fact he made a comprehensive testamentary gift to X after creating the policy, and his overall financial situation—in discerning his true intent. Generally, when interpreting a unilateral declaration of intent, the aim is to ascertain the declarant's subjective "true meaning" as much as possible, often by looking at external evidence beyond the words themselves.

However, a beneficiary designation in an insurance contract, while a unilateral act by the policyholder, has significant implications for the insurer. Insurers handle a vast number of policies and cannot realistically be expected to be aware of, or investigate, each policyholder's personal affairs, such as the existence of wills or the details of their assets, unless formally notified in a contractually prescribed manner. Therefore, at least in the context of the relationship between the policyholder and the insurer, it is generally considered inappropriate to delve into the policyholder's unexpressed, internal intentions by departing from the objective meaning of the written designation. The Supreme Court's decision in this case, much like the 1983 case concerning the "wife, [Name]" designation, aligns with this objective approach to interpreting insurance contracts.

An interesting point, though reportedly not argued by X in the appeal, was whether A's subsequent act of making a comprehensive testamentary gift of his entire estate to X could have been interpreted as an implied revocation or change of the earlier beneficiary designation in the insurance policy.

5. Acquisition Timing of the Claim Right:

A notable aspect of the Supreme Court's decision is its statement that the right to the insurance claim "becomes the heirs' proper property simultaneously with the insurance contract taking effect". This was considered by some to be a shift from previous Daishin-in precedents, which were often interpreted as the right arising at the time of the insured event (death).

In the specific context of A's case, whether the heirs acquired the right at the inception of the contract or at A's death did not change the ultimate outcome: the insurance proceeds were not part of A's estate at the time of his death and therefore were not subject to the comprehensive testamentary gift to X. For this reason, the Court's pronouncement on the exact timing of acquisition might be viewed as obiter dictum (a statement not essential to the decision).

Some inheritance law scholars maintain that the insurance claim right, by its very nature, only comes into existence upon the death of the insured. According to this view, the insured person never possesses this right during their lifetime, and therefore, it could never have been part of their heritable estate.

The Supreme Court's formulation—that the right is acquired when the contract takes effect—serves to strongly emphasize that the heirs acquire this right originally and directly due to the operation of the insurance contract as a third-party beneficiary agreement. It reinforces that the right does not flow from the deceased's estate. It is important to note, however, that the judgment does not delve deeply into the fundamental legal nature of the insurance claim right itself or the precise status of the beneficiary before the insured event occurs.

Implications of the "Proper Property" Classification

The classification of life insurance proceeds payable to "heirs" as their proper property, rather than as part of the deceased's estate, has several consequences:

- Exclusion from General Estate: The proceeds are not subject to the terms of a will concerning the general estate (as seen in X's case with the comprehensive gift) nor are they typically distributed according to intestacy rules if the heirs are already receiving them directly.

- Nuance in Specific Legal Contexts: Despite being "proper property," the treatment of these proceeds can be more nuanced in other specific legal situations. For example:

- 遺産分割 (Isan Bunkatsu - Estate Division): In distributions among multiple heirs, these proceeds might still be considered when determining equitable shares, particularly if there are significant disparities.

- 特別受益 (Tokubetsu Jueki - Special Benefit): If one heir receives substantial life insurance proceeds designated for "heirs," this might be treated as a "special benefit" that could be factored into calculating their share of the rest of the estate, to ensure fairness to other heirs. A Supreme Court decision from October 29, 2004, touches upon this, indicating complexity.

- 遺留分 (Iryūbun - Legally Reserved Portion): Questions can arise as to whether such proceeds should be included in the calculation base for the "legally reserved portion" of an estate, which certain heirs (like a spouse or children) are entitled to regardless of a will.

- Creditors' Claims: In situations like a limited acceptance of inheritance (where heirs limit their liability for the deceased's debts to the extent of the inherited assets) or the bankruptcy of the deceased's estate, the question of whether these "proper property" insurance proceeds can be accessed by the deceased's creditors requires careful, separate consideration based on the specifics of the case and relevant statutes.

Thus, while the "proper property" designation is clear for general purposes, its interaction with various aspects of inheritance law and debtor-creditor relations involves detailed analysis of the specific circumstances and the underlying policy objectives of those distinct legal areas.

Significance of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's 1965 decision remains a cornerstone in Japanese insurance law for several reasons:

- Default Interpretation for "Heirs": It establishes a clear default rule: designating "heirs" as beneficiaries means the individuals who are legal heirs at the time of the insured's death, and they receive the proceeds as their own property.

- Reinforcement of Third-Party Beneficiary Contract Principles: The ruling firmly frames such designations within the concept of a contract for the benefit of others, where beneficiaries acquire rights directly from the contract.

- Separation from Decedent's Estate: It clearly distinguishes these insurance proceeds from the general assets of the deceased's estate, impacting how wills and intestacy rules apply to them.

- Flexibility via "Special Circumstances": The inclusion of the "special circumstances" proviso allows courts to consider evidence of a contrary intent by the policyholder, ensuring that the rule is not applied rigidly against clear evidence.

Concluding Thoughts

The Japanese Supreme Court's 1965 ruling on the designation of "heirs" as life insurance beneficiaries provides critical guidance. It highlights that such a designation generally directs the proceeds to the statutory heirs as their personal assets, outside the deceased's estate. This underscores the power of the insurance contract to create direct entitlements. However, the decision and subsequent legal discourse also reveal that while this principle is clear, its interplay with specific facets of inheritance law, such as equitable distribution among heirs or the rights of creditors, can present further complexities requiring careful legal analysis. For policyholders, the case emphasizes the need for clarity in expressing their intentions, and for all parties, it illustrates the distinct path life insurance proceeds can take compared to other assets upon an individual's death.