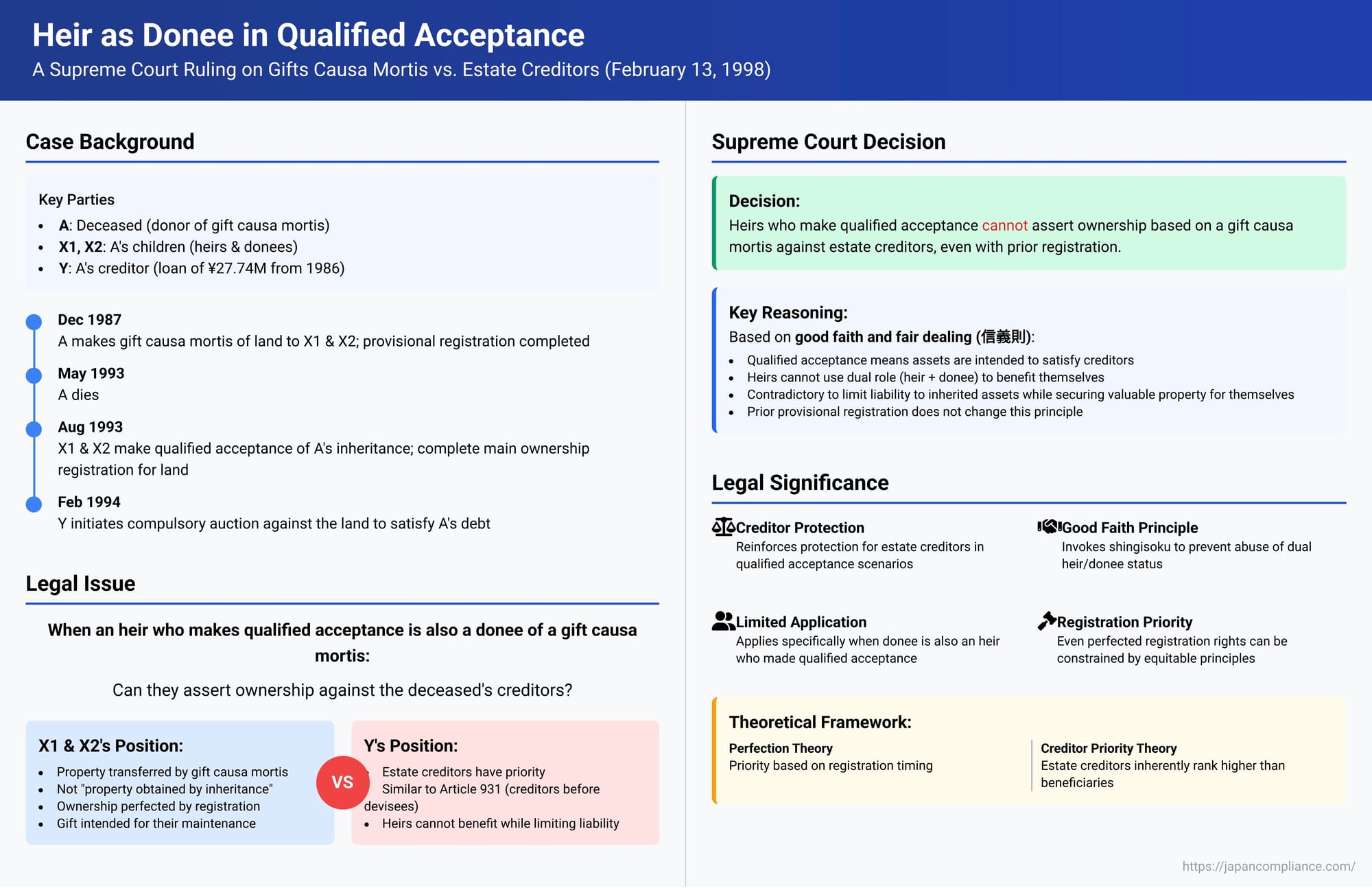

Heir as Donee in Qualified Acceptance: A Supreme Court Ruling on Gifts Causa Mortis vs. Estate Creditors

Date of Judgment: February 13, 1998 (Heisei 10)

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. Heisei 8 (o) No. 2168 (Third-Party Objection Suit)

When an individual inherits an estate, they may choose a "qualified acceptance" (限定承認 - gentei shōnin). This allows them to accept the inheritance with the crucial limitation that their liability for the deceased's debts is confined to the extent of the inherited assets. But what happens if these same heirs were also designated to receive specific property from the deceased through a "gift causa mortis" (死因贈与 - shi'in zōyo – a gift made in anticipation of, and taking effect upon, death)? Can they claim this gifted property for themselves, free from the claims of the deceased's creditors, especially if they have registered their ownership based on the gift? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this complex interplay of qualified acceptance, gifts causa mortis, and creditor rights in its decision on February 13, 1998.

Facts of the Case: A Gift, An Inheritance, and a Creditor's Claim

The case involved the estate of A and a dispute between his children (who were both his heirs and donees) and one of A's creditors.

- The Deceased and the Heirs/Donees: A was the original owner of a parcel of land ("the Property"). His children were X1 and X2 (the plaintiffs/appellants). (A had divorced his wife B in March 1986, and B was designated as the person with parental authority for X1 and X2, who were minors at that time).

- The Gift Causa Mortis and Provisional Registration: In December 1987, A made a gift causa mortis of the Property to his children, X1 and X2, to be held in equal 1/2 shares. A provisional registration (仮登記 - karitōki) was completed at that time. This type of registration serves to preserve the priority of a future claim to ownership, in this case, the transfer that would occur upon A's death.

- A's Death and Qualified Acceptance by Heirs: A passed away in May 1993. Following his death, in August 1993, X1 and X2, as A's legal heirs, formally applied for and were granted a "qualified acceptance" of A's inheritance. This legal step meant they agreed to inherit A's assets but stipulated that their responsibility for A's debts would be limited to the value of those inherited assets.

- Completion of Registration for the Gift: On August 4, 1993 (around the time they were pursuing qualified acceptance), X1 and X2 completed the main ownership transfer registration (本登記 - hontōki) for the Property. This main registration was based on the priority established by their 1987 provisional registration, and it officially recorded them as the owners of the Property by virtue of the gift causa mortis from A.

- The Creditor's Claim and Enforcement: Y (Nihon Fudosan Credit Kabushiki Kaisha, the defendant/appellee) was a creditor of the deceased A, holding a significant loan claim that originated on December 8, 1986 (for over ¥27.74 million plus accrued interest). In February 1994, Y, having secured an executory title (an instrument of execution, in this instance based on a notarial deed executed between Y and A), initiated compulsory auction (foreclosure) proceedings (本件強制競売 - honken kyōsei keibai) against the Property. Y sought to seize and sell the Property as part of A's estate to satisfy A's outstanding debt. While an initial court dismissed Y's auction application, an appellate court (the Tokyo High Court, in a decision dated October 25, 1994) overturned this dismissal and remanded the matter, which led to the auction proceedings against the Property commencing.

- Lawsuit by Heirs/Donees to Block Auction: In response, X1 and X2 filed a third-party objection lawsuit. Their primary aim was to halt the compulsory auction of the Property. They argued that:

- The Property had been transferred to them by A through the gift causa mortis, which took effect upon A's death, and their ownership was perfected by the main registration that benefited from the priority of the earlier provisional registration. Therefore, the Property was their own personal asset, acquired by gift, and not "property obtained by inheritance" (相続によって得た財産 - sōzoku ni yotte eta zaisan) that would be subject to A's debts under the terms of their qualified acceptance (as per Article 922 of the Civil Code).

- They also contended that the gift causa mortis was intended for their maintenance and support (particularly given their status as children from A's divorced marriage) and was not made with the intent to unjustly prejudice A's creditors.

- Lower Court Rulings in the Third-Party Objection Suit:

- First Instance Court: This court ruled in favor of X1 and X2. It found that the ranking-preservation effect of the provisional registration meant that X1 and X2 could validly assert their ownership (acquired via the gift causa mortis and perfected by the main registration) against Y, the creditor. The court thus considered the Property to be the exclusive property of X1 and X2, not an asset of A's estate available to satisfy A's creditors under the qualified acceptance.

- High Court: The High Court reversed the first instance decision and ruled in favor of Y (the creditor). The High Court drew an analogy to Article 931 of the Civil Code, which explicitly states that in cases of qualified acceptance, an executor must satisfy estate creditors before fulfilling obligations to devisees (recipients of testamentary gifts or 遺贈 - izō). Since gifts causa mortis are often treated similarly to devises (see Article 554 of the Civil Code), the High Court found no compelling reason to treat X1 and X2 (as donees) more favorably than devisees, even though a provisional registration for the gift had been made. Thus, A's creditors should have priority.

- Appeal by X1 and X2 to the Supreme Court: X1 and X2 appealed the High Court's adverse decision.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Good Faith Prevents Heirs from Prioritizing Gift Over Creditors

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that allowed the creditor to proceed against the Property.

The Supreme Court's core reasoning was based on the principle of good faith and fair dealing (信義則 - shingisoku):

When the donee of a gift causa mortis of real property is also an heir of the donor, and that heir has made a qualified acceptance of the inheritance, the heir cannot assert their ownership acquired through the gift causa mortis against the estate creditors of the donor, even if the ownership transfer registration based on the gift was completed before an attachment registration was made by the creditors.

The Court elaborated on this with the following points:

- Primary Purpose of Estate Assets in Qualified Acceptance: The Court emphasized that property belonging to a deceased individual is, in principle, intended to be used by the heir(s) who have made a qualified acceptance to satisfy the claims of the estate creditors. This is the very essence of qualified acceptance – liability is limited to these assets.

- The Contradictory Dual Role of the Heir/Donee: It is contrary to the principle of good faith for an heir, who has voluntarily chosen qualified acceptance (thereby acknowledging the existence of creditors and limiting their own liability for debts to the value of the inherited assets), to then simultaneously act in their capacity as a donee to secure the gifted property for themselves. In such a situation, the heir is effectively acting as both the recipient of the gift (the registration applicant or right-holder) and, by virtue of being an heir, stands in the shoes of the deceased donor regarding the obligation to transfer the property (the registration obligor). To use this dual position to complete an ownership transfer registration for themselves, thereby removing the asset from the pool available to creditors, is not consistent with good faith.

- Prevention of Unfair Outcomes: If an heir/donee could assert their ownership from a gift causa mortis against estate creditors merely by completing their registration first, an inequitable situation would arise. The heir/donee would not only be absolved from paying the deceased's debts beyond the value of other remaining estate assets (due to the qualified acceptance) but would also gain full ownership of the valuable gifted property. This would unfairly diminish the pool of assets available to satisfy the estate creditors and create a significant imbalance between the interests of the qualified-accepting heir/donee and the creditors.

- Irrelevance of Provisional Registration in This Specific Context: The Court stated that this good faith principle applies regardless of whether the final ownership transfer registration was based on a prior provisional registration. While a provisional registration generally preserves priority, its effect cannot override the fundamental obligations of good faith that arise when an heir who has opted for qualified acceptance is also the recipient of a substantial gift from the deceased's assets.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1998 Supreme Court decision is a crucial ruling that clarifies the relationship between gifts causa mortis, qualified acceptance by heirs, and the rights of estate creditors:

- Strong Protection for Estate Creditors under Qualified Acceptance: The judgment significantly reinforces the protection afforded to estate creditors when heirs choose the path of qualified acceptance. It prevents heirs from using a gift causa mortis from the deceased as a mechanism to extract valuable assets from the estate for their personal benefit while simultaneously limiting their liability for the deceased's debts.

- Application of the Good Faith Principle (Shingisoku): The Court’s explicit reliance on the broad principle of good faith and fair dealing is a key feature of this decision. It underscores that legal rights, even those seemingly perfected by registration, cannot be exercised in a manner that is fundamentally unfair or abusive, especially when an individual occupies a dual role with potentially conflicting interests (as both an heir responsible for estate administration under qualified acceptance and a donee).

- Analogy to Devises and Article 931: The High Court had already drawn a parallel with Article 931 of the Civil Code, which mandates that under qualified acceptance, estate creditors must be paid before devisees receive their testamentary gifts. The Supreme Court's decision, by focusing on the good faith principle, arrives at a functionally similar outcome for gifts causa mortis when the donee is an heir who has made a qualified acceptance. This aligns with Article 554 of the Civil Code, which states that provisions concerning devises apply mutatis mutandis to gifts causa mortis.

- Crucial Distinction: Donee is an Heir Who Made Qualified Acceptance: It is vital to understand that this ruling is specifically tailored to the situation where the donee of the gift causa mortis is also an heir of the donor and has made a qualified acceptance of the inheritance. The outcome might differ significantly if the donee were a third party unrelated to the inheritance process. In such a case, a straightforward application of property law principles, including the priority of registration (Article 177 of the Civil Code) and the ranking-preservation effect of a provisional registration, might well lead to the third-party donee prevailing over estate creditors. The PDF commentary references earlier case law (e.g., Supreme Court, Showa 31.6.28) where a provisional registration for a payment in substitution (a form of security) did protect a third party.

- Navigating "Perfection/Opposability Theory" vs. "Estate Creditor Priority Theory": Legal commentary discusses two main theoretical approaches to the priority between devisees/donees and estate creditors under qualified acceptance:

- The "Perfection/Opposability Theory" (対抗関係説 - taikō kankei setsu) would generally determine priority based on who first perfects their rights (e.g., by registration).

- The "Estate Creditor Priority Theory" (相続債権者優先説 - sōzoku saikensha yūsen setsu) argues that estate creditors inherently rank higher than beneficiaries of gratuitous transfers like devises, largely based on Article 931.

The High Court in this case appeared to lean towards the creditor priority theory. The Supreme Court, by invoking the good faith principle, effectively achieved creditor priority in the specific factual matrix where the heir and donee were the same person who had opted for qualified acceptance, without needing to make a sweeping pronouncement on which general theory applies in all circumstances.

- Scope and Motive for the Gift: The PDF commentary raises further questions, such as whether the outcome would change if the gift causa mortis was demonstrably made for essential support or maintenance of the heir (as X1 and X2 had argued), or if other specific "meritorious" circumstances existed. The Supreme Court's ruling in this case appears quite firm in subordinating the heir-donee's claim to those of the estate creditors when qualified acceptance is in play, seemingly regardless of such motives, due to the overriding good faith considerations tied to the act of qualified acceptance itself.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1998 decision serves as a critical safeguard for estate creditors when heirs attempt to benefit from a gift causa mortis from the deceased while simultaneously limiting their liability for the deceased's debts through a qualified acceptance. By applying the principle of good faith, the Court prevents such heirs from using their dual status as donee and heir to prioritize their personal gain over their obligations to ensure that the deceased's assets are, first and foremost, available to satisfy creditors. This ruling underscores that even formally registered property rights can be constrained by overarching equitable principles when their assertion would lead to an unjust outcome within the specific framework of qualified acceptance.