Heir Apparent, Shareholder In Limbo: Standing to Sue in Japanese Family Company Disputes

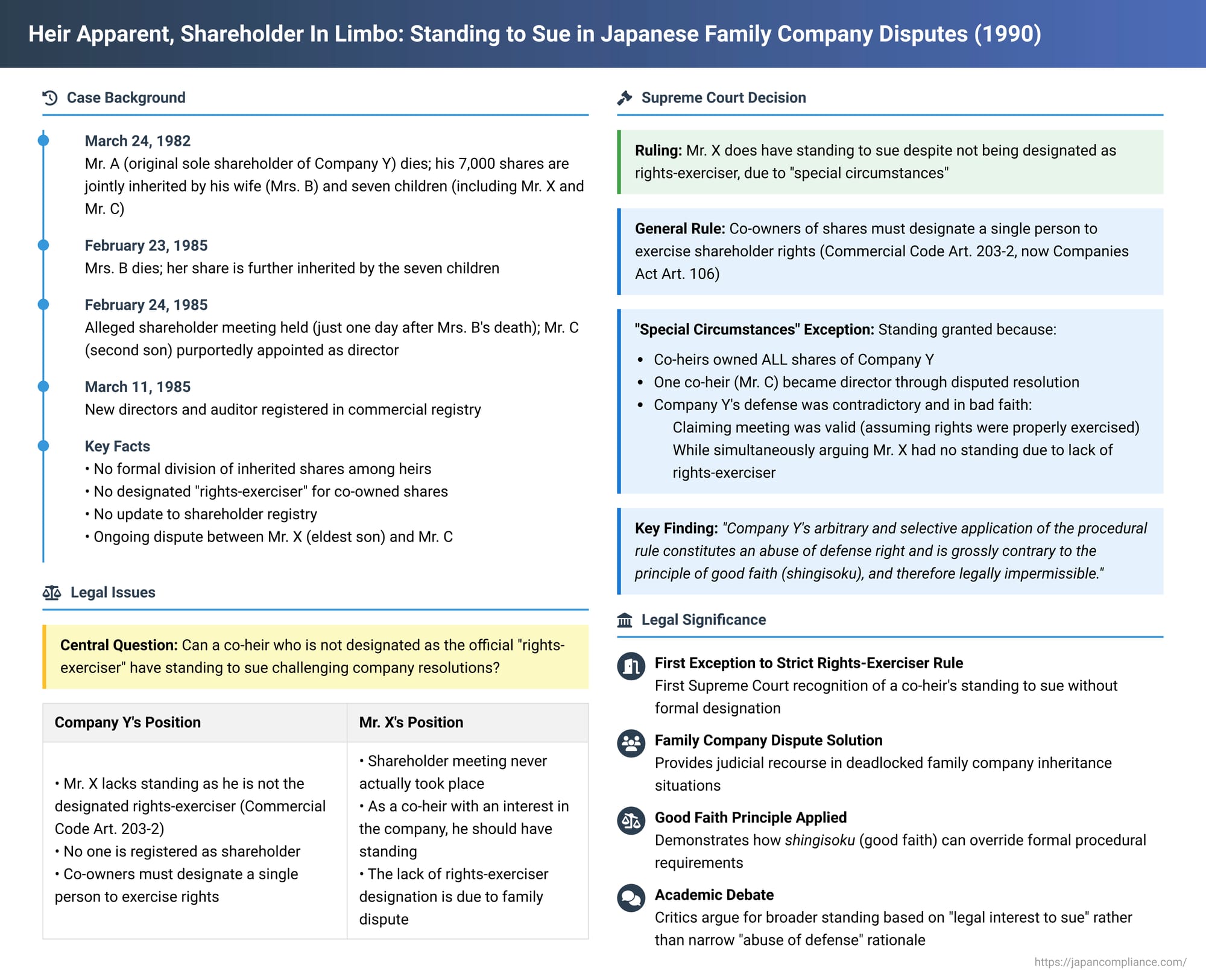

When shares in a company are passed down through inheritance to multiple heirs, complex legal issues can arise, particularly if the heirs cannot agree on how to manage their co-owned shares or if disputes erupt over control of the company. Japanese company law generally requires co-owners of shares to designate a single person to exercise shareholder rights. But what happens when such a designation is impossible due to family discord, and one heir suspects malfeasance in the company's management? A Japanese Supreme Court decision on December 4, 1990, addressed the crucial question of whether an individual co-heir, lacking formal designation as the "rights-exerciser," could nevertheless have standing to sue the company to challenge the validity of alleged shareholder resolutions, especially in the context of a closely-held family corporation.

The Facts: A Family Feud and a Phantom Meeting

The case involved Company Y, which had originally been a one-person company with all its 7,000 shares owned by Mr. A. Upon Mr. A's death on March 24, 1982, his entire shareholding was jointly inherited by his wife, Mrs. B, and their seven children. Among these children were Mr. X (the plaintiff and eldest son) and Mr. C (the second son, who would later become the representative director of Company Y).

The situation became more complex when Mrs. B also passed away on February 23, 1985. Her inherited portion of the shares was then, in turn, jointly inherited by the seven children, further consolidating the co-ownership among them.

Crucially, the co-heirs had not reached an agreement on the formal division of the inherited shares (isan bunkatsu kyōgi). Moreover, a dispute had arisen between Mr. C and Mr. X concerning the ultimate ownership and control of these shares. As a result of this ongoing discord, two critical procedural steps mandated by company law had not been taken:

- The share ownership had not been formally updated in Company Y's shareholder registry to reflect the individual co-heirs.

- No single person had been designated from among the co-heirs to be the "person to exercise shareholder rights" (kenri kōshisha) on behalf of all co-owners, and no such designation had been notified to Company Y. This designation is a requirement under the then-Commercial Code Article 203, Paragraph 2 (a provision similar to Article 106 of the current Companies Act).

Despite this situation, Company Y asserted that a shareholder meeting had been held on February 24, 1985—the very day after Mrs. B's death. At this alleged meeting, resolutions were purportedly passed to appoint Mr. C and two others as directors, and another son, Mr. D (the third son), as an auditor. These appointments were subsequently registered in the commercial登記 on March 11, 1985.

Mr. X contested these events. He filed a lawsuit against Company Y seeking a judicial declaration that no such shareholder meeting on February 24, 1985, had ever actually taken place and, consequently, that the purported resolutions appointing the new directors and auditor were non-existent (a type of lawsuit known as 株主総会決議不存在確認の訴え - kabunushi sōkai ketsugi fusonzai kakunin no uttae).

In response, Company Y challenged Mr. X's legal standing (genkoku tekikaku) to bring such a lawsuit. The company argued that:

- Mr. X was not listed as a shareholder in the company's official shareholder registry.

- Even if Mr. X had co-inherited an interest in the shares, as a mere co-owner (or holder of a shared interest - 持分権者 mochibunkenja), he was not entitled to individually exercise shareholder rights—including the right to sue regarding shareholder resolutions—without the formal designation of a single rights-exerciser as required by law.

Lower Courts: Favoring the Heir's Right to Challenge

The lower courts, however, were sympathetic to Mr. X's position regarding his standing to sue.

- The Nagoya District Court (First Instance) ruled in favor of Mr. X. It reasoned that a lawsuit for a declaration of non-existence of a shareholder resolution is not exclusively limited to registered shareholders. Instead, anyone who has a legitimate legal interest in seeking such a declaration can bring the suit. Given the unresolved inheritance dispute among the family members and the ongoing conflict over the ownership of Company Y's shares, the District Court found that Mr. X had a valid interest in legally determining whether the company's governing organs (directors and auditor) had been lawfully appointed.

- The Nagoya High Court (Appellate Court) affirmed the District Court's decision, upholding Mr. X's standing for substantially the same reasons. Company Y then appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Nuanced Ruling: Balancing Formality and Fairness

The Supreme Court, in its Third Petty Bench judgment, dismissed Company Y's appeal and upheld the lower courts' decisions that Mr. X had standing to sue. However, its reasoning introduced important nuances.

1. The General Rule Regarding Co-owned Shares:

The Court began by reaffirming the general legal principle concerning co-owned shares:

- When shares are co-owned by multiple individuals as a result of inheritance (forming a quasi-co-ownership, 準共有 - junkyōyū), the co-heirs must, in accordance with the provisions of Commercial Code Article 203, Paragraph 2 (now Companies Act Article 106), designate one person from among themselves to exercise the rights of a shareholder.

- They must then notify the company of this designated "rights-exerciser."

- Only this designated individual is then entitled to exercise shareholder rights on behalf of all co-owners.

- This principle, the Court stated, generally applies even when a co-heir wishes to file a lawsuit based on their status as a quasi-co-owning shareholder, such as a suit for a declaration of non-existence of a shareholder resolution.

- Therefore, if a co-heir has not been designated as the rights-exerciser and has not notified the company accordingly, that co-heir, as a general rule, lacks standing to sue, absent special circumstances. The Court cited its own 1970 precedent in support of this general rule.

2. The "Special Circumstances" Exception:

Despite affirming this general rule, the Supreme Court found that the present case involved "special circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) that justified granting Mr. X standing to sue, even though the formal designation and notification of a rights-exerciser were lacking. These special circumstances were:

* The shares co-inherited by Mr. X and his siblings constituted all of the issued shares of Company Y. This meant the co-heirs collectively were the entire body of shareholders.

* A shareholder resolution was alleged to have been passed appointing one of these co-heirs (Mr. C, the plaintiff's brother) as a director of the company, and this appointment had been officially registered in the commercial registry.

3. The Rationale for the Exception: Abuse of Procedural Defense and Violation of Good Faith (Shingisoku)

The Supreme Court's reasoning for carving out this exception was grounded in the principles of procedural fairness and good faith:

- The Court noted that the purpose of Commercial Code Article 203, Paragraph 2 (requiring a designated rights-exerciser) is primarily to promote the administrative convenience of the company in its dealings with shareholders, by providing a single point of contact.

- In a situation like the present case—where all company shares are co-owned by a group of heirs, and one of them is supposedly appointed director by a resolution of these very shareholders—for Company Y to simultaneously:

- Argue in the substantive part of the lawsuit that a valid shareholder meeting was held and effective resolutions were passed (which implicitly assumes that shareholder rights were properly exercised by or on behalf of the co-owning shareholders); AND

- Challenge the plaintiff co-heir's (Mr. X's) standing to sue by pointing to the lack of a formally designated rights-exerciser among those same co-owning shareholders...

...is a fundamental contradiction.

- The Supreme Court characterized Company Y's defense strategy as follows:

- By arguing that Mr. X lacked standing because no rights-exerciser was designated, the company was, in effect, implicitly admitting a fatal flaw in the purported shareholder meeting itself. If no one was properly designated to exercise the co-owned shares' rights, how could any valid resolutions have been passed by the "shareholders" at all?

- This stance was also a denial of the company's own position regarding the validity of the resolution in the main part of the legal battle.

- The Court concluded that this constituted an arbitrary and selective application (恣意的な使い分け - shiiteki na tsukaiwake) of the procedural rule (Art. 203(2)) within the same lawsuit. Such conduct amounts to an abuse of the right to present a procedural defense (訴訟上の防御権を濫用 - soshōjō no bōgyoken o ran'yō shi) and is grossly contrary to the principle of good faith (shingisoku) (著しく信義則に反し - ichijirushiku shingisoku ni hanshi), and therefore legally impermissible.

- Conclusion on Standing: Given these "special circumstances" and the company's contradictory and bad-faith defense, the Supreme Court held that Mr. X did possess the requisite standing to bring the lawsuit for a declaration of non-existence of the shareholder resolution. The High Court's decision affirming his standing was, therefore, upheld in its conclusion.

Understanding Co-owned Shares and the "Rights-Exerciser" Rule (Companies Act Art. 106)

This case highlights the practical challenges posed by Article 106 of the Japanese Companies Act (and its predecessor, Commercial Code Art. 203(2)).

- Purpose of the Rule: When shares are held by multiple co-owners (typically arising from joint inheritance, where the shares are considered to be in quasi-co-ownership, junkyōyū, among the heirs until the estate is formally divided ), the law requires them to designate one person from among them (or a third party) to exercise the shareholder rights associated with that block of shares. The company must be notified of this designation. This rule is primarily for the company's administrative convenience, allowing it to deal with a single representative for communications, voting, dividends, etc., rather than having to engage with potentially numerous co-owners individually for the same share block.

- Problem in Closely-Held Family Companies: In small, closely-held companies, especially family businesses, the death of a major shareholder often leads to shares being inherited by multiple family members. If disputes arise over succession to company control or the division of the estate (as happened in this case), the co-heirs may be unable or unwilling to agree on designating a rights-exerciser. A strict, formalistic application of Article 106 in such deadlock situations could lead to a situation where no shareholder rights can be exercised for the co-owned shares. This, in turn, could allow a faction that gains de facto control of the company management (perhaps through other means or by exploiting the deadlock) to operate without effective oversight from other co-owning shareholders, potentially to their detriment.

The Impact and Limits of the "Special Circumstances" Approach

The Supreme Court's 1990 decision was significant as it was the first time the highest court explicitly recognized an exception to the general rule requiring a designated rights-exerciser, thereby allowing a co-heir to sue under "special circumstances." This ruling has influenced subsequent similar cases.

However, the PDF commentary highlights that this approach, based on finding an "abuse of defense" or "violation of good faith" by the company, has faced criticism from legal scholars.

- Narrowness of the Exception: Critics argue that predicating the exception on the company adopting a contradictory litigation stance makes it too narrow. It might not provide a remedy for co-heirs in all situations where they have a legitimate need to challenge corporate actions but where the company's defense is not so clearly contradictory.

- Alternative Arguments for Broader Standing:

- Some scholars contend that a suit for a declaration of non-existence of a resolution should be available to any party who can demonstrate a sufficient legal interest in the outcome, regardless of their status as a formally designated rights-exerciser. This was, in fact, the position taken by the lower courts in this very case.

- Others argue that at least for lawsuits challenging the validity of shareholder resolutions (e.g., for nullity or non-existence), co-heirs should generally be granted standing if they have a legal interest. This is seen as necessary to prevent abuse by those in de facto control of a company, particularly in closely-held situations.

- It's also argued that certain shareholder rights, especially those that are "defensive" or supervisory in nature (like the right to challenge improper resolutions), should be more broadly accessible to co-owners. Allowing such challenges is seen as upholding the principle of shareholder equality and acting as a check on potential abuses of majority power, without unduly burdening the company's day-to-day administration in the same way that multiple demands for dividend payments might. Some scholars suggest that Article 106 should not even apply to such corrective supervisory rights.

The commentary suggests that while the Supreme Court's good faith rationale provided a solution in this specific instance, relying on it exclusively might create too high a bar for "special circumstances," potentially leaving deserving co-heirs without recourse in other common family company dispute scenarios. An approach based more directly on the plaintiff's "legal interest to sue" (uttae no rieki) might offer a more flexible and practically effective way to address these disputes.

The Role of Company Consent (Companies Act Article 106 Proviso)

Article 106 of the Companies Act includes a proviso stating that even if no rights-exerciser is designated and notified by the co-owners, the company may still treat a specific person as entitled to exercise rights if the company consents to doing so. The PDF commentary notes that case law has clarified that such company consent cannot unilaterally override the actual agreement (or lack thereof) among the co-owners regarding who should exercise rights, as determined by general civil law principles of co-ownership. If a company, for its own reasons, chooses to deal with one co-owner without proper authorization from all co-owners, it does so at its own risk. This could potentially lead to liability for damages to other co-owners if their interests are harmed, and any resolutions passed based on such improperly recognized rights could be subject to challenge.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 4, 1990, decision represents a pragmatic attempt to address a common and difficult problem in Japanese family companies: how to protect the interests of co-heir shareholders when internal disputes prevent the formal designation of a rights-exerciser. While upholding the general rule requiring such designation for the exercise of shareholder rights, the Court carved out a critical exception based on "special circumstances," finding that a company's attempt to use the lack of designation to deny standing while simultaneously asserting the validity of a contested resolution constituted an abuse of defense contrary to good faith. This ruling, while lauded for its equitable outcome in the specific case, has also spurred ongoing academic discussion about whether broader grounds for standing should be recognized for co-heirs in such situations to ensure adequate oversight and prevent abuses of control in closely-held corporations.