Can Japan Deny Insurance Status to New Hospitals? Supreme Court Balances Planning & Provider Rights (2005)

TL;DR

Japan’s Supreme Court (2005) upheld a prefectural decision to deny a new hospital “Insurance Medical Institution” status because it ignored a non‑binding recommendation under the regional Medical Plan. The Court ruled that (i) the denial fit the Health Insurance Act’s clause for “extremely inappropriate” institutions, since excess beds undermine cost‑efficient insurance operations, and (ii) the restriction on entering the public insurance scheme was a reasonable, constitutional limit on occupational freedom.

Table of Contents

- Background: A New Hospital in an "Over-Bedded" Region

- The Crucial Step: Applying for Insurance Designation

- The Denial and its Rationale

- The Legal Challenge: Efficiency vs. Occupational Freedom

- The Supreme Court's Decision: Designation Denial Upheld

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

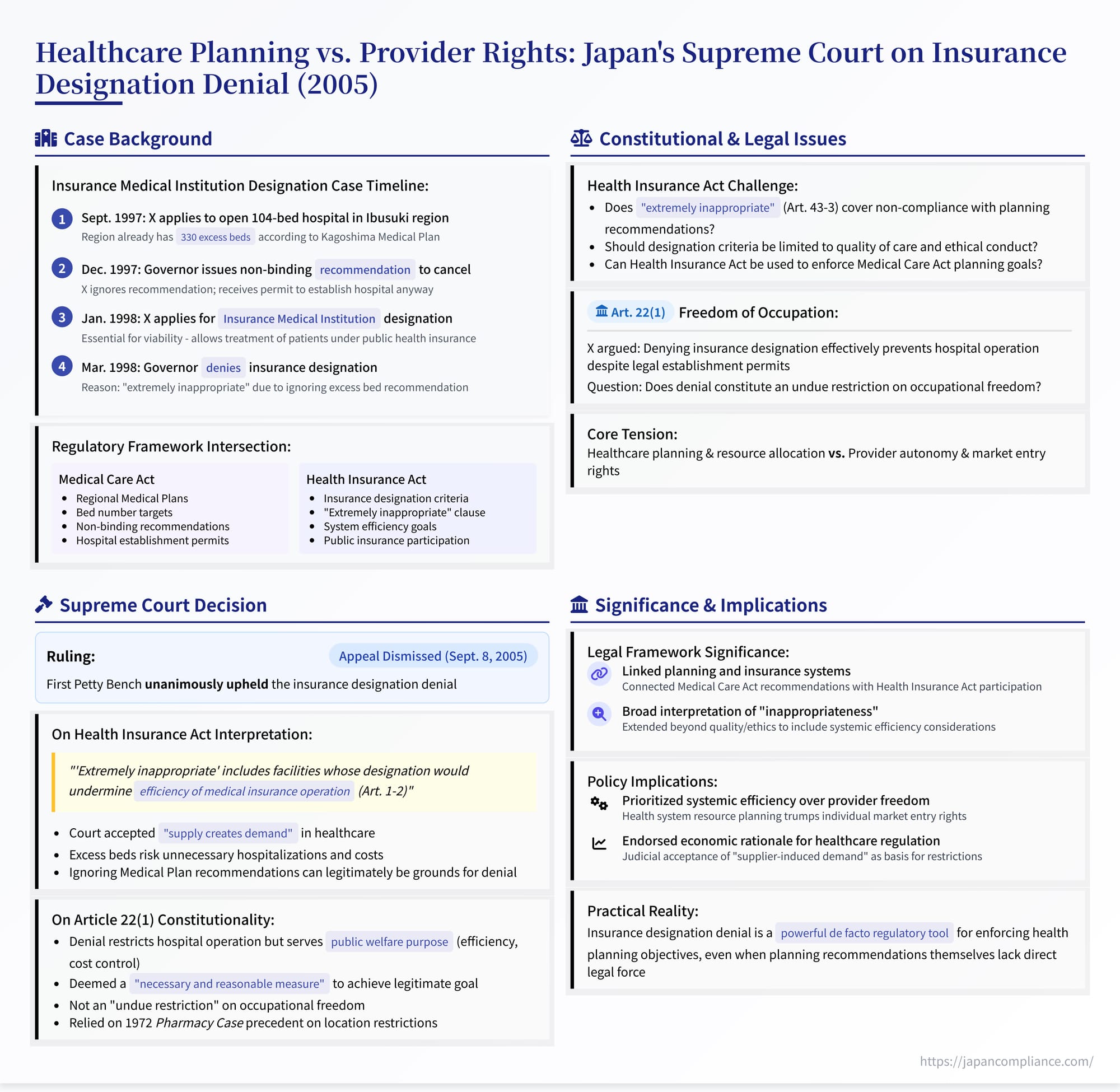

The intersection of healthcare planning, market entry, and provider rights presents complex challenges in nations striving for universal health coverage and cost control. How far can the state go in regulating the number and distribution of healthcare facilities to ensure efficiency and resource allocation, especially when such regulations impact a provider's ability to participate in the public insurance system, which is often essential for economic viability? A key Japanese Supreme Court decision from 2005 grappled with this very issue, examining the legality and constitutionality of denying designation as an "Insurance Medical Institution" to a newly opened hospital that had disregarded official recommendations based on regional health planning indicating a surplus of hospital beds. This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Disposition Denying Insurance Medical Institution Designation (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Heisei 14 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 36, Heisei 14 (Gyo-Hi) No. 39, Sept. 8, 2005), offers critical insights into the relationship between health planning regulations and the conditions for participation in Japan's public health insurance system, balanced against the constitutional guarantee of occupational freedom.

Background: A New Hospital in an "Over-Bedded" Region

The appellant, X, was an individual who operated a medical clinic in Town A, located within the Ibusuki District of Kagoshima Prefecture. Seeking to expand services, X planned to establish a new hospital in the same town. In September 1997, X applied to the Governor of Kagoshima Prefecture for permission under the Medical Care Act (医療法, Iryō Hō) to open this hospital. The proposed facility would offer services including internal medicine, surgery, neurosurgery, and rehabilitation, with a total of 104 beds.

At that time, Japan's Medical Care Act mandated prefectural governments to establish regional "Medical Plans" (iryō keikaku). These plans aimed to ensure the efficient provision of quality healthcare by, among other things, defining healthcare regions and setting target numbers for necessary hospital beds within those regions. Kagoshima Prefecture's plan designated the Ibusuki Healthcare Region (comprising Ibusuki City and the surrounding Ibusuki District, including Town A) as having a surplus of 330 general hospital beds (beds other than psychiatric, infectious disease, or tuberculosis beds). The plan identified a need for 813 such beds, while 1143 already existed in the region. However, the plan also noted that the region lacked any facility offering neurosurgery, and Town A itself had no existing hospitals.

Based on this Medical Plan and the authority granted by Article 30-7 of the Medical Care Act (allowing governors to issue non-binding recommendations to promote the plan's objectives), the Kagoshima Governor issued a formal recommendation (kankoku) to X in December 1997. Citing the fact that the Ibusuki region was designated as having excess beds and finding no special necessity for X's specific hospital, the Governor recommended that X cancel the plan to open the hospital.

X formally notified the Governor of the intent to disregard this recommendation and proceed with the hospital opening. Importantly, the Medical Care Act's criteria for granting the permit to establish a hospital (under Article 7) primarily focused on factors like staffing, facilities, and structural standards, rather than directly on the need or bed numbers stipulated in the Medical Plan. Consequently, despite X ignoring the recommendation, the Governor granted the permit to establish the hospital later in December 1997. Following this, X obtained the necessary permit to use the hospital facilities in January 1998 (under Article 27).

The Crucial Step: Applying for Insurance Designation

Having secured the necessary permits under the Medical Care Act to physically establish and operate the hospital, X took the next vital step: applying for designation as an Insurance Medical Institution (保険医療機関, hoken iryō kikan) under the Health Insurance Act (健康保険法, Kenkō Hoken Hō). In Japan's universal health insurance system, designation as an insurance medical institution is practically essential for any hospital or clinic to function viably. It allows the facility to treat patients covered by public health insurance (which includes most of the population via employer-based plans or National Health Insurance) and receive reimbursement for services from the insurance system. Without this designation, a facility can generally only treat patients paying entirely out-of-pocket, a very small fraction of the potential patient pool.

X submitted the application for designation to the Kagoshima Governor (who held the designation authority at that time) in January 1998.

The Denial and its Rationale

In March 1998, the Governor issued a disposition denying X's application for designation as an Insurance Medical Institution. The legal basis cited for the denial was Article 43-3, Paragraph 2 of the Health Insurance Act (as it existed prior to 1998 amendments). This provision listed several grounds for denying designation, including a general clause allowing denial if the facility was "otherwise deemed extremely inappropriate as an insurance medical institution or insurance pharmacy" (其ノ他保険医療機関若ハ保険薬局トシテ著シク不適当ト認ムルモノナルトキ).

The specific reason given for finding X's hospital "extremely inappropriate" was directly linked to the prior events under the Medical Care Act:

- The hospital was planned for a region identified in the Medical Plan as having excess beds.

- A formal recommendation to cancel the opening due to lack of necessity had been issued by the Governor under the Medical Care Act.

- X had disregarded this recommendation.

- Referencing administrative guidance (specifically, a 1987 notice from the MHW Insurance Bureau Director concerning the coordination between medical planning and insurance designation), the Governor concluded that opening a hospital against such a recommendation rendered it "extremely inappropriate" for designation under the Health Insurance Act's criteria.

Essentially, the denial linked non-compliance with a non-binding recommendation under the Medical Care Act (focused on facility planning and resource allocation) to the finding of "extreme inappropriateness" under the Health Insurance Act (focused on participation in the insurance system).

The Legal Challenge: Efficiency vs. Occupational Freedom

X challenged the Governor's denial of designation in court (with the Director of the Kagoshima Social Insurance Bureau later succeeding the Governor as the relevant defendant due to administrative reforms). X argued that the denial was illegal and unconstitutional:

- Illegality under the Health Insurance Act: X argued that the denial misinterpreted Article 43-3, Paragraph 2. The "extremely inappropriate" clause, X contended, should relate to factors concerning the quality of care, ethical conduct, or administrative capability of the institution itself, not its consistency with regional bed planning or compliance with non-binding recommendations under a different law (the Medical Care Act). Using the denial of designation to enforce the Medical Plan's bed targets exceeded the intended scope of the Health Insurance Act provision.

- Violation of Constitution Article 22(1) (Freedom of Occupation): X argued that denying insurance designation effectively prevented the viable operation of the legally permitted hospital, thus constituting an undue restriction on the freedom to choose and practice an occupation (including the freedom to operate a business) guaranteed by Article 22(1).

The lower courts were split. The Kagoshima District Court ruled in favor of X, finding the denial illegal. However, the Fukuoka High Court (Miyazaki Branch) reversed this, upholding the denial as both lawful under the Health Insurance Act and constitutional under Article 22(1). The High Court reasoned that efficiency in healthcare operations was a valid consideration under the Health Insurance Act, and that Article 22 did not guarantee a right to participate in the insurance system, only the right to open the hospital itself. X appealed this adverse ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Designation Denial Upheld

The First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed X's appeal, affirming the High Court's decision and finding the denial of insurance designation to be both lawful and constitutional.

1. Reasoning on Legality (Health Insurance Act Interpretation):

The Court focused on the interpretation of the denial criterion "otherwise... extremely inappropriate" within the context of the Health Insurance Act's overall objectives.

- Emphasis on Operational Efficiency: The Court highlighted Article 1-2 of the Act, which explicitly states that the health insurance system should be implemented while constantly considering and seeking to improve the "efficiency of medical insurance operation" (iryō hoken no un'ei no kōritsuka), alongside appropriateness of benefits/costs and quality of care.

- Broad Interpretation of "Extremely Inappropriate": In light of this statutory emphasis on efficiency, the Court held that the phrase "otherwise... extremely inappropriate" should be interpreted to include situations where designating the facility would be markedly inappropriate from the perspective of operational efficiency. It was not limited solely to issues like poor quality or fraudulent practices.

- The Link Between Excess Beds and Inefficiency: The Court accepted the premise, based on findings below and general understanding in health economics, that "supply tends to create demand" in healthcare. It acknowledged the correlation whereby an increase in hospital beds per capita tends to lead to increased hospitalization costs per capita.

- Applying the Logic: Therefore, designating a hospital whose beds contribute to a regional surplus already identified in the official Medical Plan (which itself aims for efficient provision) poses a risk. It could lead to unnecessary or excessive medical expenditures (as the new beds induce demand) and thereby hinder the efficient operation of the medical insurance system.

- Conclusion on Legality: Given these considerations, the Court found that denying designation to X's hospital – which was opened despite a formal recommendation (based on the goal of efficient healthcare provision outlined in the Medical Plan) advising against it due to bed surplus – was a justifiable application of the "extremely inappropriate" criterion from the perspective of operational efficiency. The denial did not violate Health Insurance Act Article 43-3, Paragraph 2.

2. Reasoning on Constitutionality (Article 22 - Freedom of Occupation):

The Court then addressed the claim that the denial constituted an unconstitutional restriction on occupational freedom.

- Nature of the Restriction: The Court acknowledged that denying insurance designation imposes a significant practical restriction on operating a hospital in Japan. However, it framed the issue not as a direct prohibition on the occupation of running a hospital (which X was legally permitted to do under the Medical Care Act permit), but as a regulation of participation in the public insurance scheme.

- Public Welfare Justification: The Court found the denial, based on non-compliance with the recommendation aimed at promoting the Medical Plan and healthcare efficiency, served a legitimate public welfare purpose. This purpose was identified as ensuring the efficient operation of the health insurance system and preventing potentially wasteful or unnecessary healthcare spending funded by that system.

- Necessary and Reasonable Measure: The Court characterized the denial of designation in these specific circumstances (disregarding a formal recommendation based on planned resource allocation) as a "necessary and reasonable measure" (hitsuyō katsu gōri-teki na sochi) undertaken to achieve this legitimate public welfare goal.

- No Undue Restriction: Consequently, the Court concluded that denying designation under these conditions did not constitute an "undue restriction" (futō na seiyaku) on the freedom of occupation guaranteed by Article 22(1).

- Reliance on Pharmacy Case Precedent: The Court explicitly stated that this conclusion was clear based on the principles established in the landmark 1972 Pharmacy Case (Supreme Court, Grand Bench). That case upheld regulations restricting the location of new pharmacies based on geographical distribution needs and public welfare considerations, establishing the principle that occupational freedom under Article 22(1) is not absolute and is subject to reasonable regulations necessary for the public good. The Court saw the denial of designation in this case as a similar, permissible regulation aimed at the public welfare goal of healthcare system efficiency.

Therefore, the Supreme Court upheld the High Court's decision and dismissed X's appeal.

Significance and Analysis

The 2005 Supreme Court decision in this case holds significant implications for the regulation of healthcare providers and the interplay between different strands of health policy in Japan.

- Linking Health Planning and Insurance Participation: The ruling powerfully connects the regional health planning system under the Medical Care Act (specifically, the Medical Plans and associated recommendations regarding bed numbers) with the conditions for participation in the public health insurance system under the Health Insurance Act. It establishes that actions taken contrary to official (even if non-binding) health planning recommendations aimed at resource rationalization can serve as a valid basis for denying access to the crucial insurance reimbursement system.

- Broad Scope of "Inappropriateness" for Designation: The decision confirms a broad interpretation of the grounds for denying insurance designation. The clause "otherwise... extremely inappropriate" is not limited to factors like quality deficiencies or misconduct within the facility itself but can encompass broader systemic considerations related to the efficient allocation of healthcare resources and the financial health of the insurance system. This gives regulators significant leverage.

- Judicial Acceptance of "Supplier-Induced Demand" Rationale: The Court explicitly accepted the economic argument regarding supplier-induced demand in healthcare and its potential impact on costs as a valid justification for restricting market entry (specifically, entry into the insurance payment system) in areas deemed to have excess capacity according to official plans.

- Occupational Freedom vs. Systemic Efficiency: The case clearly delineates the boundaries of occupational freedom (Article 22) within the heavily regulated healthcare sector. It affirms that the freedom to establish and operate a medical facility is subject to significant restrictions deemed necessary for the public welfare, particularly the goal of maintaining an efficient and sustainable universal health insurance system (which serves the broader objectives of Article 25). The ruling effectively prioritizes planned resource allocation and systemic cost control over an individual provider's absolute freedom to participate in the public insurance market if their entry conflicts with those plans.

- Practical Impact of Designation Denial: The judgment underscores the practical reality of healthcare provision in Japan: while obtaining a permit under the Medical Care Act allows a hospital to legally exist, the denial of designation under the Health Insurance Act makes its viable operation virtually impossible. Thus, the designation decision becomes a powerful de facto regulatory tool for enforcing health planning objectives related to resource distribution, even if the planning recommendations themselves are not legally binding directives for establishment.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2005 ruling affirmed the legality and constitutionality of denying health insurance designation to a hospital established against official recommendations based on regional bed surplus identified in the Medical Plan. The Court held that such a denial was permissible under the Health Insurance Act's "extremely inappropriate" clause, interpreting it to include considerations of operational efficiency and cost control within the insurance system. Furthermore, it ruled that this restriction, aimed at the public welfare goal of efficient healthcare resource management, constituted a necessary and reasonable limitation on the freedom of occupation guaranteed by Article 22 of the Constitution. The decision solidifies the link between healthcare planning and insurance system participation in Japan, granting significant weight to regional Medical Plans and prioritizing systemic efficiency in the balance against individual provider rights.