Healing Across Borders: Japan's Supreme Court on Medical Aid for Overseas A-Bomb Survivors

Date of Judgment: September 8, 2015

Case: General Medical Expenses Payment Application Dismissal Disposition Revocation, etc. Claim Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction: The Enduring Legacy of the Atomic Bombings

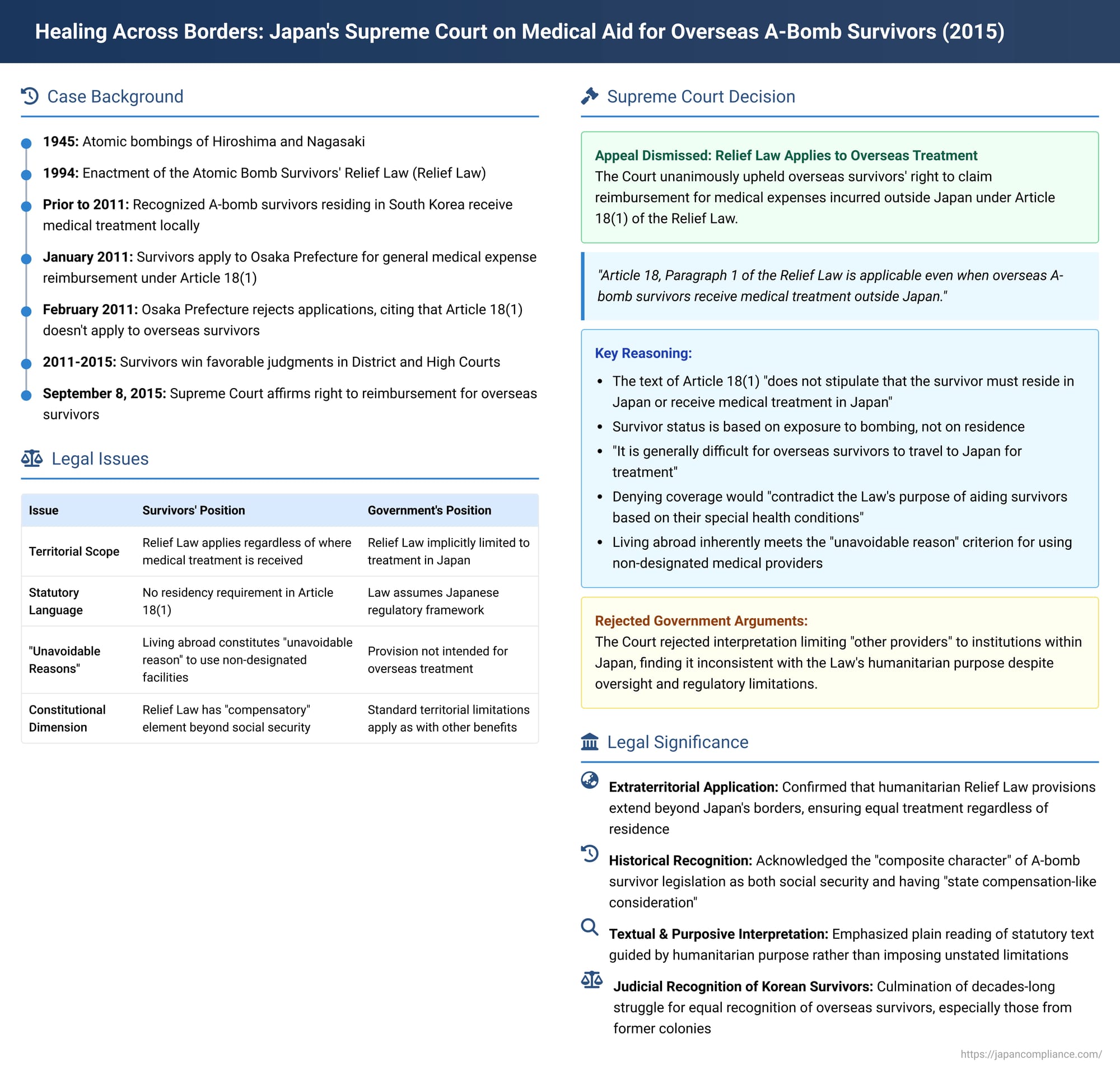

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 left a uniquely devastating legacy, not only in terms of immediate destruction but also through the long-term health consequences faced by survivors, known as hibakusha. In response, the Japanese government enacted the Atomic Bomb Survivors' Relief Law (the "Relief Law"), a comprehensive piece of legislation aimed at providing medical care and other forms of support to those affected. A crucial question that arose over the decades was whether the provisions of this law extended to survivors who, for various reasons, came to reside outside of Japan. Specifically, could these overseas survivors claim reimbursement for medical expenses incurred in their countries of residence? This issue was definitively addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant judgment on September 8, 2015.

The Plight of Overseas Survivors: X and Others' Case

The case involved X and others, individuals who had been exposed to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and were officially recognized as A-bomb survivors, holding A-bomb Survivor Health Handbooks issued under the Relief Law. These survivors were residing in the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and had received medical treatment there for various illnesses.

In January 2011, applications were filed on their behalf with the Governor of Osaka Prefecture seeking reimbursement for these medical expenses. The claim was made under Article 18, Paragraph 1 of the Relief Law, which pertains to "general medical expenses" (i.e., medical costs for illnesses not specifically recognized as A-bomb related diseases, which are covered under a different section of the law).

However, in February 2011, the Governor of Osaka Prefecture, following consultation with the national government, rejected these applications. The stated reason for rejection was that Article 18, Paragraph 1 of the Relief Law was deemed inapplicable to "overseas A-bomb survivors" (zaigai hibakusha) – defined as certified survivors who do not have a place of residence or current location within Japan. The Prefecture's position was that medical treatment received outside Japan by survivors living abroad did not qualify for reimbursement under this provision.

X and others (or their successors, as some of the original survivors passed away during the lengthy legal process) challenged these rejections. They filed a lawsuit against Osaka Prefecture seeking the revocation of the dismissal dispositions. They also lodged a related claim for state compensation against both Osaka Prefecture and the national government, alleging illegality in the rejections and in the national government's guidance.

The Lower Courts' Stance: Upholding Overseas Coverage

The path through the lower courts was favorable to the survivors regarding the medical expense claims. Both the Osaka District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (appellate instance) ruled in their favor. These courts ordered the revocation of the Governor's rejection dispositions, finding that overseas A-bomb survivors were indeed entitled to claim general medical expenses under the Relief Law for treatment received abroad. The state compensation claims, however, were dismissed by these courts, and this aspect was not the primary focus of the subsequent Supreme Court appeal initiated by Osaka Prefecture. The Prefecture specifically appealed the part of the High Court judgment that upheld the survivors' right to medical expense reimbursement.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: Relief Law Applies Extraterritorially

The Supreme Court, in its Third Petty Bench decision, dismissed Osaka Prefecture's appeal. This landmark judgment affirmed that Article 18, Paragraph 1 of the Relief Law applies to overseas A-bomb survivors for medical treatment received outside Japan. The Court's reasoning was grounded in a textual and purposive interpretation of the Law:

1. Core Reasoning - Purpose and Text of the Law:

The Supreme Court meticulously analyzed the Relief Law's objectives and provisions:

- Fundamental Purpose: The Court began by emphasizing the Relief Law's foundational purpose: to provide aid and support to A-bomb survivors, recognizing the "uniqueness and severity of the health damage caused by the radiation of the atomic bombs" and focusing on the "special health conditions" in which survivors find themselves. This purpose, the Court implied, is humanitarian and centered on the survivor's status as a hibakusha.

- Survivor Status Irrespective of Residence: The Court noted that the Relief Law defines who qualifies as an A-bomb survivor based on criteria related to their exposure to the bombings (Article 1). Obtaining an A-bomb Survivor Health Handbook confirms this status. Crucially, this recognition as a survivor is not contingent upon residing in Japan.

- Article 18(1) - No Residency Requirement: Examining Article 18, Paragraph 1, which governs the payment of general medical expenses, the Court found that it simply specifies "A-bomb survivors" as eligible recipients. The text "does not stipulate that the survivor must reside in Japan or receive medical treatment in Japan as a condition for payment."

- Treatment by Non-Designated Institutions: Article 18(1) explicitly covers situations where survivors receive medical care from institutions other than those specifically designated by prefectural governors under the Law. The Court found "no provision limiting these 'other providers' to those operating within Japan."

- Practical Realities and Humanitarian Intent: The Court acknowledged a practical reality: "It is generally difficult for overseas survivors to travel to Japan for medical treatment." It then reasoned that if these survivors were "completely unable to receive reimbursement for medical treatment obtained outside Japan, it would contradict the Law's purpose of aiding survivors based on their special health conditions."

2. Addressing Government Counterarguments:

Osaka Prefecture, reflecting the national government's stance, had argued that the Relief Law implicitly assumes a framework of Japanese domestic medical regulations designed to ensure the safety and quality of care. Furthermore, to ensure the proper administration of benefits, the Law grants the Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare oversight powers (e.g., requesting reports, inspecting medical records) over medical providers, including non-designated ones. Since these Japanese regulatory and oversight mechanisms cannot extend to medical institutions outside Japan, the government contended that the "other providers" mentioned in Article 18(1) should be interpreted as being limited to those within Japan.

The Supreme Court rejected this line of argument. It held that, given the clear text of Article 18(1) and the overall humanitarian purpose of the Relief Law, adopting such a restrictive interpretation—effectively reading in an exclusion for overseas treatment despite the absence of explicit statutory language to that effect—would be contrary to the Law's fundamental intent and therefore "not appropriate."

3. Interpretation of "Emergency or Other Unavoidable Reasons":

Article 18(1) establishes a general rule that survivors should seek treatment from designated medical institutions. Payment for treatment from non-designated institutions is conditional upon there being an "emergency or other unavoidable reason." The Supreme Court provided important guidance on this condition in the context of overseas survivors. It reasoned that if a survivor in Japan receives treatment from a nearby non-designated institution because no designated institution is available in their vicinity, this would satisfy the "unavoidable reason" criterion. By analogy, the Court stated, "this interpretation can be applied similarly to overseas A-bomb survivors receiving treatment outside Japan." Since, by definition, Japanese-designated medical institutions are not available to survivors in their countries of residence abroad, this effectively means that overseas survivors seeking local medical care inherently meet this "unavoidable reason" condition.

Conclusion of the Court:

Based on this comprehensive analysis, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Article 18, Paragraph 1 of the Relief Law is applicable even when overseas A-bomb survivors receive medical treatment outside Japan."

Therefore, the Governor of Osaka Prefecture's rejection of the applications—which was made without any assessment of whether the specific conditions of Article 18(1) (such as the nature of the illness or the "unavoidable reason" for seeking treatment from a non-designated provider) were met, but solely on the categorical ground that the provision does not apply to overseas survivors receiving overseas treatment—was illegal.

The Legal and Historical Context: State Compensation and Social Security

This 2015 judgment builds upon a history of legal interpretation concerning the unique nature of A-bomb survivor relief. A key Supreme Court precedent from 1978 had characterized earlier A-bomb survivor legislation (the A-bomb Medical Care Law) as possessing a "composite character." This meant it was primarily a social security law aimed at providing medical care, but it also contained an element of "state compensation-like consideration" (kokka hoshōteki hairyo). This "compensatory" aspect stemmed from the recognition that the unprecedented health damage was ultimately a consequence of a state act (war) and that survivors often found themselves in more precarious life circumstances than general war victims. This composite nature implied that principles typically applied to other social security laws, such as strictly limiting benefits to legal residents, might not be fully applicable to A-bomb survivor relief.

While the 2015 Supreme Court cited this 1978 precedent, it did not extensively re-litigate the "composite character" theory. Instead, it achieved its conclusion through a more direct interpretation of the Relief Law's text and stated purposes. Legal commentators suggest this approach was sufficient, as the underlying "compensatory consideration" likely remained a background assumption. The specific protective needs of A-bomb survivors, recognized by the Law's humanitarian objectives, lent strong support to an inclusive interpretation.

Furthermore, the principle of Japanese social security schemes covering overseas medical expenses is not entirely without precedent. Standard Japanese public health insurance systems, for instance, already have provisions for reimbursing certain medical expenses incurred by insured persons while abroad ("kaigai ryōyōhi"). The Relief Law also contains mechanisms to ensure that reimbursements for overseas medical care do not lead to uncontrolled or excessive costs, as payments are generally capped at the lower of the actual expense or the amount calculated based on Japanese domestic health insurance fee schedules.

Implications of the Ruling: Extraterritorial Application and Ongoing Issues

The 2015 Supreme Court decision marked a significant victory for overseas A-bomb survivors and their advocates. It firmly established the extraterritorial application of Article 18(1) of the Relief Law, ensuring that essential medical expense support for general illnesses is not denied based on a survivor's country of residence or where they receive treatment.

This judgment is a culmination of decades of legal struggles by overseas survivors, many of whom were forcibly displaced or chose to live abroad after the war. Through persistent litigation, they have gradually secured recognition and the application of various provisions of the Relief Law, including the issuance of A-bomb Survivor Health Handbooks and the payment of certain allowances, irrespective of their place of residence.

The practical implementation of these rights for overseas survivors involves Japanese authorities exercising a form of extraterritorial jurisdiction—both prescriptive (the law applies) and enforcement (benefits are delivered abroad). This is generally understood to occur with the voluntary submission of the overseas survivors to Japanese procedures and at least the tacit consent or acquiescence of their countries of residence.

Despite this significant progress, it is noted by legal experts that some disparities may still exist in the full range of support measures available to overseas survivors compared to those residing in Japan. The path to comprehensive and equal relief has been long and arduous.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's decision of September 8, 2015, stands as a crucial affirmation of the humanitarian and reparative principles underpinning Japan's A-bomb Survivors' Relief Law. By focusing on the Law's text and its fundamental purpose of alleviating the unique suffering caused by atomic bomb radiation, the Court ensured that access to necessary medical expense support for general illnesses is not contingent upon geographical location.

This ruling recognizes that the special health conditions and needs of A-bomb survivors transcend national borders. It represents an important step in ensuring that the commitment to aid these individuals is applied inclusively, acknowledging the global diaspora of hibakusha and their right to seek care where they live. The judgment champions a purposive approach to statutory interpretation, ensuring that the Law's compassionate intent is given meaningful effect for all recognized survivors, wherever they may reside.