Hazardous Bargains? Japan's Supreme Court on State Liability for Defective Goods Sold at Customs Auctions

Judgment Date: October 20, 1983

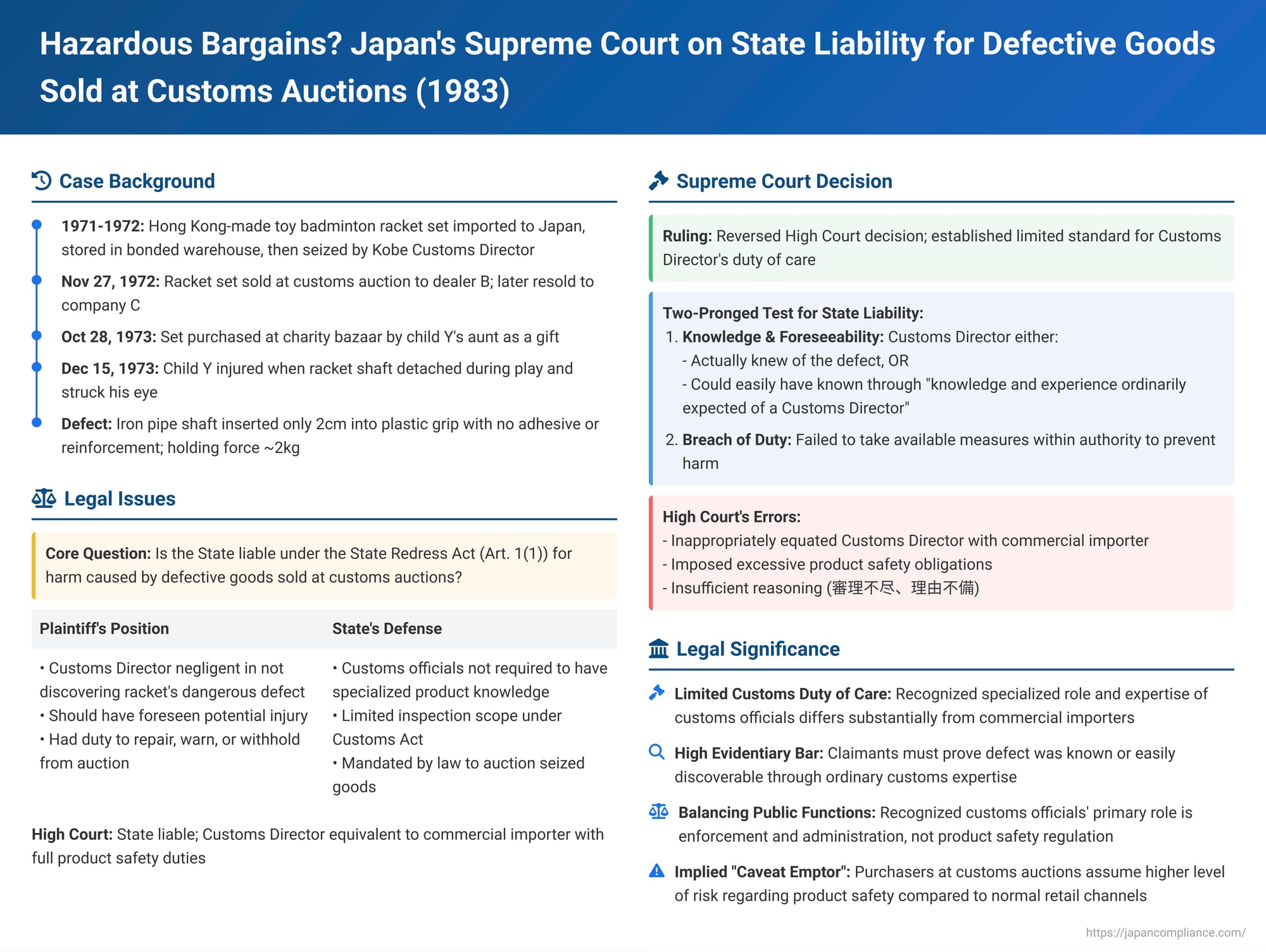

Customs auctions are a common method for governments worldwide to dispose of goods that have been seized or remain unclaimed. While offering potential bargains, what happens if an item purchased at such an auction turns out to be defective and causes harm to an eventual end-user? Can the State be held liable for the actions of its customs officials in inspecting and auctioning such goods? This complex question of state liability was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, in a significant judgment on October 20, 1983 (Showa 54 (O) No. 1309), often referred to as the "Defective Badminton Racket Case."

The Incident: A Defective Toy Racket from a Customs Auction Leads to Injury

The plaintiff, Y, was a child who, on December 15, 1973, was playing badminton with his older brother using a racket from "the Racket Set." During play, the shaft of "the Racket" suddenly detached from its grip, flew through the air, and struck Y in the left eye, causing injury.

The Racket Set, consisting of two rackets and a shuttlecock packaged in a polyethylene bag, had a somewhat convoluted history:

- It was manufactured in Hong Kong and bore only the marking "MADE IN HONG KONG" on the racket head.

- The set was imported into Japan, arriving at Kobe Port on December 18, 1971, and was subsequently stored in a bonded warehouse.

- As the importer was unknown or failed to complete customs procedures, the Kobe Customs Director seized the goods on June 13, 1972, under Article 79, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Customs Act (which allows seizure of goods requiring permits/approvals for import that are not obtained, or for which duties are not paid). The goods were classified as "toys."

- Around November 1972, Customs officials conducted inspections. This typically involved a special appraisal section determining auction reserve prices, tariff classifications, and tax rates by examining samples, and a warehousing section conducting quantity checks and deciding if goods should be discarded.

- On November 27, 1972, the Racket Set was sold at a public auction by the Customs Director, pursuant to Article 84, Paragraph 1 of the Customs Act (which mandates public sale for most seized goods that are not otherwise disposed of).

- A sundries dealer, B, purchased the set at this auction.

- B sold it to an intermediary company, C (Sato Brothers Ltd.), on December 2, 1972.

- Company C offered the set for sale at a charity bazaar on October 28, 1973, where Y's aunt, A, purchased it and gifted it to Y on the same day.

Post-accident examination revealed the defect: the Racket's iron pipe shaft was inserted only about two centimeters into its polyethylene plastic grip and was held merely by the plastic's tension, without any adhesive, pins, or other reinforcing fasteners. The grip on the accident Racket was found to have cracked to its edge, and the other racket in the set also showed a significant crack in its grip. Tests indicated that the grip's holding force was low (around 2kg for the accident Racket), and that the centrifugal force generated by a 4-5 year old child swinging the racket forcefully could easily exceed this, creating a "considerable possibility" of the shaft detaching. Furthermore, the polyethylene used for the grip was known to degrade over time due to heat, UV light, and stress, and the tight insertion of the chrome-plated (and thus relatively slippery) shaft into the plastic grip was found to likely accelerate this degradation.

The Legal Claim: Holding the State Responsible for Customs' Actions

Y (the injured child, through his representatives) sued the State of Japan (X), arguing that the Kobe Customs Director and his officials had been negligent. The core of the claim was that the customs officials should have detected the Racket's structural defect during their pre-auction inspection and should have foreseen that auctioning such a dangerous item could lead to an accident like the one that befell Y. It was argued that the Customs Director had a duty to either repair the defect, warn potential buyers, or refrain from auctioning the hazardous item.

The Osaka High Court (second instance) had found the State liable. It reasoned that the Customs Director's sale of seized goods was essentially a private law sale. By putting the Hong Kong-made Racket Set into circulation within Japan, the Customs Director assumed a position analogous to that of a commercial importer and therefore owed a duty of care similar to that of a manufacturer or seller regarding product safety. The High Court concluded that the Customs Director could and should have foreseen the risk of such an accident and was negligent in not taking preventative measures. The State appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Defining and Limiting the Customs Director's Duty of Care

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision, finding that the lower court had applied an incorrect standard for the Customs Director's duty of care. The Supreme Court established a more limited basis for state liability in such cases, emphasizing the specific role and expertise of customs officials.

The Court laid out a two-pronged test for determining if the State could be held liable under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Redress Act when auctioned seized goods cause harm due to defects:

- Knowledge and Foreseeability of Defect by Customs Officials:

- Liability could arise if the Customs Director, during the course of inspections conducted pursuant to the Customs Act (primarily under Article 84, Paragraph 5, to determine if goods are perishable, likely to decrease in value, or difficult to store, thus warranting quicker disposal or different handling), actually knew of the structural defect or other relevant flaw in the goods.

- Alternatively, liability could arise if the defect was such that the Customs Director, through the exercise of knowledge and experience ordinarily expected of a Customs Director (税関長の通常有すべき知識経験 - zeikan-chō no tsūjō yūsubeki chishiki keiken), could easily have known of its existence.

- Furthermore, it must be shown that the Director foresaw, or reasonably should have foreseen, that if the defective goods were sold at public auction, they could end up in the hands of an end-consumer in their defective state and cause harm through ordinary use within a reasonable period.

- Breach of Duty to Prevent Harm (within the scope of authority):

- If such knowledge and foreseeability were established, it must then be shown that the Customs Director could have taken measures to prevent such harm to the end-consumer and had a legal duty to do so, but negligently failed to take such measures.

The Rationale Behind This More Limited Standard:

The Supreme Court provided clear reasons for not holding Customs Directors to the same stringent product safety standards as commercial manufacturers or importers:

- Limited Expertise and Scope of Inspection: Customs officials deal with an immense variety and volume of seized goods. They do not possess, nor are they legally required to possess, the specialized technical knowledge concerning the design, materials, manufacturing processes, and potential defects of every conceivable product that passes through their hands. Their inspections under the Customs Act are primarily for purposes such as tariff classification, valuation, ensuring compliance with import restrictions, and determining the appropriate method of disposal (e.g., public auction, destruction, etc.), not for conducting exhaustive product safety engineering assessments. Therefore, to equate a Customs Director with a manufacturer or a regular commercial importer in terms of product safety duties would be inappropriate. Liability for failing to detect a defect can only arise if the defect was actually known or would have been easily discoverable through the ordinary knowledge and experience expected of a customs official performing their statutory duties.

- Limited Powers and Obligations Regarding Rectification or Withholding from Sale: Even if a Customs Director becomes aware of a defect, their options are constrained by law:

- The Customs Act generally mandates that seized goods (not deemed "disposable" due to perishability, etc., under Art. 84(5)) must be put to public auction (Art. 84(1), (3)). The primary purpose is to clear bonded warehouse space and, where applicable, recover unpaid customs duties or other state claims. There is generally no broad discretion to simply withhold non-prohibited, non-perishable goods from auction indefinitely if they have some value.

- The Customs Director does not own the seized goods and has no general legal authority or obligation to undertake repairs of defects.

- The Supreme Court suggested that if a defect were known, the appropriate measures available to a Customs Director might be limited to actions such as informing the auction purchaser of the defect or contractually obliging the purchaser to rectify the defect before resale, and ensuring such an obligation is met. If such available measures were taken, the Director's duty to prevent harm to eventual end-consumers might be considered fulfilled.

High Court's Errors Identified by the Supreme Court:

Based on this framework, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred:

- It had too readily concluded that the Kobe Customs Director knew of the Racket's specific structural issues and could have foreseen the precise nature of the accident. The Supreme Court found this conclusion lacked sufficient deliberation and proper reasoning based on the limited duties of a customs official (審理不尽、理由不備 - shinri fujin, riyū fubi).

- It had incorrectly equated the Customs Director's duties and responsibilities with those of a commercial importer, thereby imposing an inappropriately high standard of care regarding product safety.

The Supreme Court therefore reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for a re-examination based on the stricter and more nuanced standard of care and foreseeability applicable to a Customs Director.

Implications of the "Ordinary Customs Expertise" Standard

This 1983 Supreme Court ruling significantly clarifies the limits of state liability for defective goods sold at customs auctions:

- High Evidentiary Bar for Claimants: It establishes a high threshold for those seeking to hold the State liable. A claimant must do more than simply prove the product was defective and caused harm. They must demonstrate that the defect was something the Customs Director actually knew about or should have easily known within the scope of their ordinary duties and expertise.

- Focus on Actual or Readily Apparent Defects: Liability is unlikely for latent defects, design flaws requiring specialized engineering knowledge to identify, or issues that would only become apparent through extensive product testing, unless Customs had actual, specific notice of such problems.

- Customs' Primary Role Is Not General Product Safety Regulator for Auctioned Goods: The judgment reinforces that the primary functions of customs authorities regarding seized goods are related to the enforcement of customs laws (tariffs, import restrictions), administration of bonded areas, and the orderly disposal or sale of goods as mandated by statute. They are not positioned or equipped to act as a general product safety regulator for all items that pass through their auctions.

- Implied "Caveat Emptor" for Auction Buyers (and Subsequent Purchasers): While not explicitly stating "buyer beware," the ruling suggests that purchasers at customs auctions, and those who subsequently acquire such goods down the line, assume a certain level of risk regarding the condition and safety of items, especially if the items are of unknown origin or unusual construction. This risk is heightened when dealing with goods that have been seized and are sold outside normal commercial distribution channels.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in the "Defective Badminton Racket Case" sets a crucial precedent regarding the scope of state liability for injuries caused by defective goods sold at customs auctions. It establishes that the State's responsibility, acting through its customs officials, is not equivalent to that of a manufacturer or commercial importer. Liability will only arise if customs officials knew of a specific defect or if the defect was so apparent that it should have been easily discovered through the exercise of ordinary customs expertise during their statutory inspection duties, and they then negligently failed to take appropriate measures within their limited authority to prevent harm. This ruling underscores the specific and somewhat circumscribed nature of a customs official's duty of care with respect to the safety of the myriad goods they handle and ultimately sell at public auction.